- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Contemporary Nationalism

About this book

This book examines the problematic politics of contemporary nationalism, and the worldwide resurgence of ethno-nationalist conflict. It analyses the core theories of nationalism, building upon these theories and offering a clear analytical framework through which to approach the subject. This outstanding volume features detailed case- studies discussing nationalist contention in areas including Spain, Singapore, Ghana and Australia as well as looking at Northern Ireland, Kosovo and Rwanda disputes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The conceptual languages of nationalism

In 1963 Clifford Geertz referred to the ‘stultifying aura of conceptual ambiguity’ surrounding the subject of nationalism (Geertz 1963:107). Since then, there has been a remarkable growth of perceptive works on the topic, but in the opinion of several influential writers on nationalism, the concept still refers to an ‘unsteady mixture [of ideas]…unsuitable for clear analytical thought’ (Dunn 1995:3. Also Periwal 1995). 1

The problem is sometimes explained as arising from the fact that nationalism is a ‘category of practice’, as well as a ‘category of analysis’ (Brubaker 1996:15). This implies that it is the very conceptual ambiguities which make it so useful for mobilising or manipulating political action in a wide variety of situations, which undermine its utility for clear explanation. Nations are often defined as communities united by their ‘moral conscience’ or their consciousness of themselves as a nation. This faces analysts of nationalism with a particular problem. Should they accept these self-definitions as their defining criterion of nationhood: should they accept these self-definitions only when they coincide with other ‘objective’ criteria (linguistic or genetic, for example); or should they depict these self-definitions as interesting symptoms in need of diagnosis?

Given the varying responses of different writers on nationalism to this problem, it is evident that we need a map of the terrain. One possibility is to seek such a map by tracing the ‘historical evolution of nationalist thought’ (Dahbour and Ishay 1995:1), and guiding a reader down this evolutionary road; examining the major contributions, from both practitioners and analysts, along the way. Unfortunately, the evolutionary road begins to look rather like a maze, as similar conceptual approaches keep reappearing. The aim in this first chapter, therefore, is to offer clarification by disentangling three conceptual languages, which each generate distinct stories as to the nature of contemporary nationalist politics. The first story explains such politics as the assertion of the natural primordial rights of ethnic nations against contemporary multi-ethnic states; the second sees contemporary nations as in the process of being transformed by situational changes in the structure of the global economy; and the third sees assertions of nationalism as arising out of the search for new myths of certainty, constructed to resolve the insecurities and anxieties engendered by modernisation and globalisation.

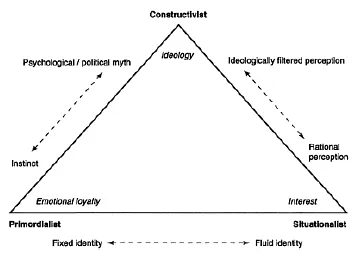

These three conceptual languages, which see nationalism as, respectively, an instinct (primordialism), an interest (situationalism) and an ideology (constructivism), provide the nodal points within which the various writers on nationalism may be located (Figure 1). They are outlined here to show how they each generate differing stories as to the relationship between ethnicity and nationalism, the rise of nation-states, and the problematical character of contemporary nationalist politics. But they are also outlined in order to support the suggestion that one of these languages, the constructivist language which portrays nationalism as an ideology, might be preferred because it seems to answer some of the unresolved questions raised by the other approaches. The comparison of the three conceptual languages in this first chapter, thus paves the way for a more extended development and application of the constructivist approach in subsequent chapters.

The different approaches have sometimes been used to refer to different types of identity, contrasting an instinctual and primordial identity in less-developed societies, usually labelled ‘tribalism’, with an allegedly more rational form of affiliation in the developed west, deserving of the title ‘nationalism’; and distinguishing also between the authentic nationalist sentiment of the masses, and the xenophobic nationalist fictions sometimes articulated and manipulated by élites. No such distinctions are made here. Members of all national communities tend to believe that preferential loyalty to their communities is in some sense natural. The primordialist approach seeks to validate and specify that perception; the situationalist approach depicts it as the manifestation of rational interests; and the constructivist approach sees it as a politically constructed myth. Hitherto, the distinction between the three

Figure 1 National identity—the three conceptual languages

approaches has been made most explicit in discussions of ethnicity, but since the concepts of ethnicity and nationalism are so closely intertwined, it seems likely that the disentangling of the three approaches might also clarify debates on nationalism. 2

A primordialist approach to the study of nationalism

Primordialist approaches depict the nation as based upon a natural, organic community, which defines the identity of its members, who feel an innate and emotionally powerful attachment to it. Natural nations have natural rights to self-determination.

We need to begin by recognising the confusion which surrounds the term ‘primordialism’, and which persists because few writers on ethnicity and nationalism make their primordialist assumptions explicit. 3 The problem arises because the term is used sometimes to refer to a sense of identity, and sometimes also to refer to a particular kind of explanation for that sense of identity. 4 The belief that one is born into a particular linguistic, racial or homeland community, and therefore inevitably feels an overwhelming emotional bond with that community, is sometimes referred to as the ‘primordial bond’. The primordialist explanation for this belief is, in effect, that it is true. The argument is that humanity has indeed evolved into distinct, organic communities, each with their own language and culture, with each individual’s sense of identity derived from their location within one such community. When nations claim to be communities of common ancestry, they are, from the primordialist perspective, essentially correct. Primordialism thus explains the conflict and violence which characterises much of modern nationalist politics as arising from the discontinuity between the boundaries of the natural national communities which deserve and seek political autonomy, and those of the modern states. The fact that these modern states are usually called, and call themselves, ‘nations’, is regarded from this perspective either as a mistake, or as a politically motivated trick (Connor 1994:90–117).

It is immediately apparent that, from this perspective, the only authentic nationalism is ethnic nationalism. The ethnic group is that community which claims common ancestry and sees the proof of this in the fact that its members display distinctive attributes relating to language, religion, physiognomy or homeland origin. The ethnic community is also characterised by the belief on the part of its members that there exists a natural emotional bond between the individual and the community, and that ethnic consciousness is indeed a central component of individual identity. The ethnic community thus constitutes an ethical community, whose members see themselves as having prior moral obligations to each other, over and above any obligations they owe to other communities. Ethnic identity may in some circumstances be taken for granted by those concerned, and need not necessarily generate claims to political rights. But once it is actively and selfconsciously mobilised in order to legitimate claims that the ethnic community has some rights of self-determination, then ethnicity has become transformed into nationalism.

Primordialism recognises that the complex and opaque histories of contemporary national communities mean that we cannot show the factual truth of their claims to common ancestry. Indeed, most would accept Walker Connor’s formulation that the nation is ‘a group of people who feel that they are ancestrally related. It is the largest group that can command a person’s loyalty because of felt kinship ties’ (Connor 1994:202, emphasis added). But the primordialist suggestion is that such beliefs are likely to be strongest when they are most authentic. Their transmission through the generations may indeed involve some distortion and simplification; they may well be adopted by assimilating minorities; and they may well be embroidered and elaborated by intellectuals and political élites. But it is suggested that kinship ideologies articulated by élites will only engender nationalist sentiment where they resonate with the collective memories of the wider populace, and where they refer to myths of common ancestry which are substantially true.

The primordialist approach has been criticised for being unable to offer any explanatory proof as to the basis for this bond between the individual and the ethnonational community. It does however offer several lines of thought which might be insightful, if unprovable. In its simplest version, primordialism claims that nations are organic communities united by the fact of common ancestry. This view is given some support by a significant literature on sociobiology, which suggests that there might be a genetic or instinctual mechanism leading us to favour kin over non-kin; a mechanism which is functional in biological terms for the survival of the genes of the individual and of their genetic relatives (Shaw and Wong 1989, Reynolds et al. 1987). Although such a mechanism would initially seem to apply only to communities defined on a racial basis, Pierre Van den Berghe has suggested that we are programmed to favour those who appear to be genetically related, on the basis of clues in the form of similarities of language and culture (Van den Berghe 1995). This gives rise to a more subtle version of primordialism which suggests that the natural, organic basis for nations derives, not from a genetic basis, but from the innate power of cultural affinities of language, religion and custom. Karl Jung gives support for this in his suggestion that primordialism might refer to the inheritence of a collective memory, an ‘archetype of the collective unconscious’ (Jung, in Campbell 1976:56).

Many psychologists, and some contemporary communitarian theorists, suggest, however, that such ‘group memories’ are better explained in terms of the overwhelming influence of the primary socialisation processes, whereby the culture of a society is transmitted through the generations, in part from parents to children, but also in part through the public channels of religion, literature, education and the arts, so that the identity of the adult is moulded and fixed by the experiences of childhood (Black 1988, Sandel 1982). This kind of social psychological argument paves the way for what Anthony Smith has called the ‘perennialist’ variant of primordialism, exemplified in the work of Walker Connor and Donald Horowitz, in which ethnic and national groups whose pre-existence is assumed, are socialised into political consciousness by modern formulations of their common ancestry:

In this view, there is little difference between ethnicity and nationality: nations and ethnic communities are cognate, even identical phenomena. The perennialist readily accepts the modernity of nationalism as a political movement and ideology, but regards nations either as updated versions of immemorial ethnic communities, or as collective identities that have existed, alongside ethnic communities, in all epochs of human history.

(Smith 1998:159) 5

All these formulations of primordialism agree that the development of individual identity is necessarily embedded in and defined by the culture of the community of birth and childhood, which has belief in common ancestry as its focal point.

Frequently, however, primordialist approaches to nationalism do not try to specify the precise nature of the ethnonational bond, and do not indeed overtly label themselves as primordialist. One strategy is simply to claim that ethnicity and nationalism refer to an emotional and spiritual bond which is ‘ineffable’ and ‘unaccountable’ (Geertz 1973:259); which ‘can not be explained rationally…[but only] obliquely analyzed by examining the type of catalysts to which it responds’ (Connor 1994:204). Alternatively, the primordialist approach is sometimes indicated only briefly, as if it were self-evident, by merely asserting that ‘all peoples have the right to self-determination’, and leaving it implied that the oppressed, minority or indigenous people referred to, do constitute in some sense an authentic and ‘natural’ community, with a correspondingly ‘natural’ right.

The awakening of the ethnic bond, and its development into the nationalist claim, is not usually depicted as being inevitable. So long as the ethnic community retains its autonomy, ethnic identity may remain at the ‘taken for granted’ level; a ‘sleeping beauty’ until awakened by the perception that the culture, cohesion or autonomy of the community is in some way threatened. But this awakening is unlikely to be spontaneous. Ethnic consciousness, and the formulation of nationalist responses to ethnic grievances, needs to be articulated and transmitted by activists who can show the link between the present threats, the authentic past, and the future destiny. These activists act therefore as historicists (Smith 1981) who help the community to rediscover its ethnic past and therefore its continuity and destiny, so as to turn the ‘taken for granted’ ethnic identity into a conscious national pride, which can be mobilised for the defence of its right to autonomous development. Such ‘historicists’ (the storytellers, the intelligentsia, the media) can dramatise and embroider, but cannot invent, the ethnic past of the nation. 6 Any attempt at invention would fail to resonate in the culture and collective memory of the society, and so would lack the power to mobilise. The success of the mobilisation is thus proof of the authenticity of the ethnic past.

Adrian Hastings (1997) offers an argument on these lines. He recognises, with Anthony Smith, that modern nations, whose roots go ‘a very long way back indeed’ (1997:181), are ‘constructed’ only in the sense that they are ‘an almost inevitable consequence of the interaction of a range of external and internal factors’ (1997:31), with the development of a vernacular literature, and religion, being seen as the key ingredients. It is these factors which lead some ethnic communities to ‘naturally’ develop into the integral element within nations. Anthony Smith and Adrian Hastings are important because they combine primordialist and constructivist themes so as to offer subtle explanations of the continuities between modern nationalism, whose conscious collective identity and memories are generated and carried in their literature and religion; and their core ethnic roots, whose myths of common genetic descent contain, in Hasting’s words, ‘a necessary core of original truth’ (1997:169. See n. 6 in the Notes section).

During the 1950s and 1960s, primordialist approaches were applied most explicitly to the discussion of ethnic conflict in less-developed societies, on the assumption that political behaviour in such ‘backward’ societies was most likely to be based on emotion and instinct, and on ancestrally based ‘tribal’ affiliations. By the same token, it was widely assumed, at that time, that the processes of modernisation would lead to more rational forms of political behaviour as development occurred, promoting either a universalistic rationality, or at least an intrinsically democratic form of civic nationalism focused upon identification with the modern state, rather than with the community of common ancestry. But any such optimism was eroded from the late 1960s onwards, when ethnic and nationalist conflict escalated, with the onset of civil rights unrest in the USA, the conflicts of Biafra and Bangladesh, and the upsurge of violence in Northern Ireland and the Basque country. In the face of such apparent failures of the modernisation process to integrate the current nation-states in either the developed or the developing countries, primordialist approaches have revived. But, in the process, the moral evaluation of the primordialist ethnic bond has undergone some reassessment. Primordialist explanations of ethnic assertions in the third world tended in the 1950s and 1960s to depict them in negative terms, as outbursts of inward and backward-looking irrational intolerance. However, the application of this approach to the study of contemporary ethnic minority claims has depicted ethnic assertions as ethically valuable bases for individual self-fulfilment and collective self-determination.

The primordialist explanation of contemporary nationalist politics rests on the claim that the history of state-formation has been primarily one of conquest and migration. This means that virtually all modern states contain societies which are ethnically heterogeneous. The pattern of such multi-ethnicity, and the nature of their nationalist claims, varies greatly, depending upon whether the state contains several homeland communities, as in Russia; several communities claiming the same homeland, as in Israel; or several migrant communities, as in Singapore.

Such disparities in ethnic structure generate differences in the resultant politics, but from the primordialist perspective these are all variations on a common theme, which is stated most clearly in the plural society model of politics (Kuper and Smith 1969). Nationalist thinkers such as Herder and Fichte had suggested that each distinct linguistic nation ought to enjoy political self-determination by forming its own sovereign state. This was not just a moral right, it was also a prudential move—since only states formed on such an ethnic basis would be held together by the necessary common values, so that they could develop as harmonious, stable and democratic societies. States which were not ethnically homogeneous would lack such normative consensus, and would therefore tend to fragment into ethnic rivalries if they were not held together by some form of state force. The ethnocentric loyalties and disparate values of each ethnic segment would necessarily generate political tensions as to the allocation of resources and power. In Walker Connor’s words:

it is evident that for most people the sense of loyalty to one’s [ethno-]nation and to one’s state do not coincide…[W]hen the two loyalties are perceived as being in irreconcilable conflict—that is to say when people feel they must choose between them—[ethno-]nationalism customarily proves the more potent.

(Connor 1994:196)

There are two formulations of the resultant politics. One possibility is that those aspects of the modernisation process which promote integration might be actively engineered by the ‘nation-building’ activities of state élites, so that primordial ethnic sentiments can be either eroded, or accommodated within an encapsulating sense of nation-state identity. This process does make two assumptions which are, from the primordialist perspective, highly unlikely. The first is that new rational attachments to nation-states become more powerful than the emotional and instinctual primordial bonds. The second is that the state has sufficient legitimacy and managerial capacity to modify or manipulate people’s sense of identity in this way.

The other, more likely possibility, is that the élites of one of the ethnic segments in such a plural society—the largest, best organised, best educated, or the one which dominates the armed forces—manage to infiltrate or capture the state institutions of government and administration, so as to ensure that their ethnic segment retains higher cultural, economic and political status. This may be done overtly through policies of e...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The conceptual languages of nationalism

- 2 New nations for old?

- 3 Are there two nationalisms?

- 4 Constructing nationalism

- 5 Globalisation and nationalism

- 6 Reactive nationalism and the politics of development

- 7 Contentious visions

- 8 How can the state respond to nationalist contention?

- 9 Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Contemporary Nationalism by David Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.