Unit 1 The manifold nature of assessment

Assessment has so many purposes that it is not surprising that there are so many styles to go with them. If there were only one simple unambiguous purpose then assessment would be a much more straightforward matter than it is. A few years ago I knew a headteacher who boasted proudly that he had never assessed a pupil in his life. Yet he often wrote references for his school leavers, and on many occasions I saw him asking questions of his pupils. He frequently offered words of approval to those who had done something that brought credit to the school, and I once witnessed him getting very cross with a pupil who had carelessly thrown a piece of litter in the school yard, telling the pupil off and ordering him to pick the litter up. What he presumably meant was that he did not attach much importance to written examinations, but whether he liked the idea or not, he was assessing pupils’ social and intellectual progress and behaviour every day.

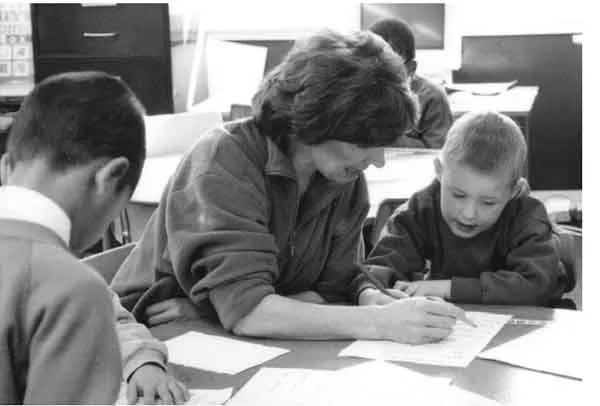

It would be easy to see assessment purely as something that teachers do to pupils on behalf of society and nothing more. There is an important element of assessment here which cannot and should not be ignored. Society often does need to know what its members have learned, especially where people are selling their services to their fellows. None of us would want to be operated on by an amateur surgeon, or have the brakes on our car repaired by an enthusiastic ignoramus. We like to believe that someone has accredited these professionals on our behalf, formally checking out their knowledge and skill, so that their certificate of qualification ensures that they are competent. The long process of appraising knowledge, skill and competence begins early in children’s lives.

Trying to assemble a log of all the occasions when children are assessed during a school day, week or year would soon produce a very full dossier. All the following are arguably different forms of assessment:

- A child shows the teacher a finished painting; the teacher says ‘Well done!’ and puts it up on the classroom wall.

- The teacher asks the class, ‘What is the capital of France?’

- Three pupils work together in a physical education lesson to improve each other’s gymnastic ability.

- The teacher sets a spelling test.

- A pupil takes her technology project to the teacher, who points out how its finish could be improved.

- At the end of their course children take a public examination in mathematics under formal timed conditions.

- A group of pupils performs a short play in front of the class, followed by a discussion of their performance by teacher and pupils.

- A teacher reprimands a pupil for misbehaving and says, ‘If you do that again you’ll stay in during break.’

- The headteacher asks two pupils with particularly good singing voices if they would like to sing a duet at the town’s music festival.

- A teacher grades a student’s portfolio of coursework for a public examination, prior to its being assessed by an external moderator.

Although these examples may be given the umbrella caption ‘assessment’, they are quite different from each other. Some are formal, like the maths exam, others are informal, like the smile and subsequent display of the child’s painting. There are examples of academic achievement being assessed, as in the coursework moderation, but also instances of social behaviour being appraised, as in the case of the pupil threatened with detention for misbehaviour. Some evaluation is external, like the public examination, most other examples are internal to the school, or are a mixture of internal and external evaluation.

The assessment is mainly carried out by teachers, but some examples illustrate self-evaluation, like the three pupils improving each other’s gymnastics. The maths exam comes at the end of a maths course and so is ‘summative’ or ‘terminal’ (though hopefully not in the ‘fatal’ sense of the word), whereas the teacher suggesting how the girl can improve her technology project is carrying out a ‘formative’ or ‘interim’ assessment, which can still influence the pupil’s finished product.

These are just a few of the many forms of assessment available to teachers. Standardised tests may have cost millions to develop over a period of a year or more. Home-made tests may have consumed hours of the teacher’s time to construct, as may the marking of pupils’ coursework. A smile, a nod or a threat of punishment may occupy a few seconds of the teacher’s and pupil’s time. Any of these may make a significant impact on children’s learning, for good or ill.

The consequences of each form of assessment may also be very different. Some, like public examination results or selection tests, may affect career choices, opportunities – someone’s whole future. Others may appear to have had little or no influence on learning and subsequent behaviour. The two pupils selected by the head for their good singing voices may one day feel encouraged to specialise in the performing arts, since they are ‘officially’ thought to be good at them. Both positive and negative consequences may follow different kinds of assessment, depending on the personality of the recipient. Some pupils may be motivated by a critical assessment and strive to improve, others may feel demolished by it and simply erect a block against the subject, topic or teacher.

One evaluation may be ‘redeemable’, in that pupils can subsequently improve their grade, while another might apply a permanent label, unless the candidate takes the whole course again.

TYPES OF ASSESSMENT

The dimensions below are presented as pairs of opposites, but in practice most teachers use some form of both types, as well as hybrid variants in between. The issues described under each of the headings are closely linked one with another, rather than separated.

Formal or informal?

No one form of assessment can suit all conceivable purposes and locations. If society decides to find out whether standards of reading amongst thousands of pupils have risen or fallen, then this sort of information cannot be gleaned solely by holding occasional conversations with individual teachers, illuminating though that exercise may be. A more formal assessment of achievement, or some kind of collecting of judgements, is necessary. On the other hand, if a teacher wants to know whether pupils have understood instructions about what clothing to bring for a school trip, the easiest and most natural approach is informal – simply to ask them, as a group or as individuals.

In most classrooms, assessment tends to be regular and informal, rather than irregular and formal. This is because teaching often consists of frequent switches in who speaks and who listens, and teachers make many of their decisions within one second (Wragg, 1999). In such a rapidly changing environment, where teachers have to think on their feet and are denied the luxury of hours of reflection over each of their pedagogic choices, assessment has to be carried out on the move. That is why so much informal assessment is often barely perceptible as the flow of the lesson continues, since it is neatly interlaced with normal-looking instruction and activities. Indeed, many teachers would not even regard the common question, ‘Is anybody not sure what you’re supposed to do?’ as assessment, but it is, informing the teacher of which pupils might need individual help before starting on the task in hand.

This last example illustrates some of the strengths and weaknesses of informal assessment. Asking the class a question is a natural event and economical of time, but some pupils may be reluctant to put up their hand and risk revealing their ignorance to their fellows. Once children are working on their assignment, it is common practice for teachers to walk round, monitoring what they are doing. Sometimes this kind of informal assessment will reveal that some pupils who were reluctant to put up their hand and ask for help in a public way are, in fact, struggling with the work and do need assistance. There are many types of informal assessment available to teachers, both public and semi-private, and one approach may be more effective than another in a particular set of circumstances.

Formal assessment is usually much more structured. Sometimes it will involve a standardised test, an examination paper, or an assessment schedule drawn up by an external body. There are normally written statements about how the assessment must be carried out, laying down how much time is available, what questions must be addressed and where the scripts or projects are to be sent afterwards. ‘Formal’ here does not mean ‘unpleasant’, or ‘threatening’, though these adjectives may sometimes apply, but rather that the exercise is governed by a predetermined set of rules and conventions, instead of being improvised according to immediate circumstances.

An example of the differences between informal and formal methods can be seen in the field of modern language teaching. During the oral part of a German lesson, the teacher may put questions in the foreign language to individuals or groups. If several pupils mispronounce the sound ‘ch’, as in the German word Kirche (meaning ‘church’), this informal assessment tells her that she will need to help them practise the correct pronunciation. Later in the lesson she may walk round looking at their written work, noticing that some pupils make mistakes when writing in the past tense. This signals that some revision and corrective work is necessary if they are to use the past tense properly in future.

Aformal assessment, however, might involve all the pupils in the class being tape-recorded, one at a time, for several minutes, answering a series of predetermined questions. They may subsequently sit in an examination room and write answers in German. Both cassettes and written scripts may then be sent away for marking. It is also possible to have a semi-formal version of assessment, perhaps with the teacher devising and then administering a simple pencil and paper test of vocabulary that pupils have recently learned, or playing a prerecorded cassette of German dialogue and asking pupils to write down answers to questions. This is formal, in that it follows certain rules and conventions, but also informal, as it is given at a suitable moment in class and barely interrupts the flow of normal teaching.

The strengths and weaknesses of varying degrees of formality are fairly clear. Teaching is a busy job, so informality can offer natural, unfussy and frequent ways of gauging progress, giving feedback, or eliciting the sort of diagnostic information that informs teachers what logical next steps might be taken. It may however, be too ad hoc and improvised to give a proper picture, and it may not always provide the degree of reflective objectivity necessary to counterbalance excessive subjectivity. Formal assessment may allow comparison with others, opportunities to measure improvement in a systematic way and also, at its best, rigorously tested and considered instruments of assessment, but may overawe the less-confident pupils, or give an incomplete picture of what they have been doing over a long period.

Continuous or final?

It is also a feature of many courses in school that pupils are assessed along the way and that they receive some kind of assessment at the end of their course. Continuous assessment is often thought to be good for pupils who are more anxious than their fellows, but Child (1977) points out that this can depend on the nature of the tasks, because pupils who are faced with a series of appraisals that they cannot manage particularly well, may become demoralised.

One central concept in teaching and learning is that of motivation. As is discussed again in Unit 2, to some extent ‘motivation’ can be defined in operational terms as the amount of time and the degree of what psychologists call ‘arousal’ that pupils apply to their learning. If motivation is high, then children will spend a great deal of time and give much attention to what they are doing. Over a period of weeks and months this ought to make a difference to their achievement in the field of study, provided the programme is well conceived and worthwhile. Continuous assessment, by offering regular feedback, may help to maximise concentration and attentiveness. If the subject of study is seen by pupils in a negative light and motivation is low, however, it may reduce time and effort spent on the programme of study.

Some of the same points about motivation can be made in the context of final or terminal assessment. Those who support end-of-course examinations argue that many pupils would not do as much work were there not some ‘official’ grade or certificate to strive for at the conclusion of the whole programme, and that this outweighs the more taken-for-granted continuous assessment.

It certainly does seem to be the case that a number of pupils will be spurred on by extrinsic motivation – that is, external rewards such as good test grades. Others respond better to intrinsic motivation; something that is seen to be worthwhile in its own right. Where continuous assessment contributes to the final overall grade, it is much more similar, in its external importance and the way it may be perceived, to final assessment. Adult life is often driven by a mixture of both extrinsic (e.g. salary or status) and intrinsic (e.g. personal satisfaction) motivation and rewards.

Coursework or examination?

Many systems of pub...