![]()

Part 1

Law

Chapter 1.1 | Explaining the law (Brenda Watts) |

Chapter 1.2 | Principal health and safety Acts (S. Simpson) |

Chapter 1.3 | Influences on health and safety (J. R. Ridley) |

Chapter 1.4 | Law of contract (R. W. Hodgin) |

Chapter 1.5 | Employment law S. Ali (with acknowledgements to R. D. Miskin) |

Chapter 1.6 | Consumer protection (R. G. Lawson) |

Chapter 1.7 | Insurance cover and compensation (A. West) |

Chapter 1.8 | Civil liability (E. J. Skellett, updated by David Greenhalgh) |

Laws are necessary for the government and regulation of the affairs and behaviour of individuals and communities for the benefit of all. As societies and communities grow and become more complex, so do the laws and the organisation necessary for their enforcement and administration.

The industrial society in which we live has brought particular problems relating to the work situation and concerning the protection of the worker’s health and safety, his employment and his right to take ‘industrial action’.

Part 1 looks at how laws are administered in the UK and the procedures to be followed in pursuing criminal actions and common law remedies through the courts. It considers various Acts and Statutes that are aimed at safe working in the workplace and also some of the influences that determine the content of new laws. Further, the processes are reviewed by which liabilities for damages due to either injury or faulty product are established and settled.

![]()

Chapter 1.1

Explaining the law

B. Watts

1.1.1 Introduction

To explain the law, an imaginary incident at work is used which exemplifies aspects of the operation of our legal system. These issues will be identified and explained with differences of Scottish and Irish law being indicated where they occur.

1.1.2 The incident

Bertha Duncan, an employee of Hazards Ltd, while at work trips over some wire in a badly lit passageway used by visitors as well as by employees. The employer notifies the accident in accordance with his statutory obligations. The investigating factory inspector, Instepp, is dissatisfied with some of the conditions at Hazards, so he issues an improvement notice in accordance with the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (HSWA), requiring adequate lighting in specified work areas.

1.1.3 Some possible actions arising from the incident

The inspector, in his official capacity, may consider a prosecution in the criminal courts where he would have to show a breach of a relevant provision of the safety legislation. The likely result of a successful safety prosecution is a fine, which is intended to be penal. It is not redress for Bertha.

The employee, Bertha, has been injured. She will seek money compensation to try to make up for her loss. No doubt she will receive state industrial injury benefit, but this is intended as support against misfortune rather than as full compensation for lost wages, reduced future prospects or pain and suffering. Bertha will therefore look to her employer for compensation. She may have to consider bringing a civil action, and will then seek legal advice (from a solicitor if she has no union to turn to) about claiming compensation (called damages). To succeed, Bertha must prove that her injury resulted from breach of a legal duty owed to her by Hazards.

For the employer, Hazards Ltd, if they wish to dispute the improvement notice, the most immediate legal process will be before an employment tribunal. The company should, however, be investigating the accident to ensure that they comply with statutory requirements; and also in their own interests, to try to prevent future mishaps and to clarify the facts for their insurance company and for any defence to the factory inspector and/or to Bertha. The company would benefit from reviewing its safety responsibilities to non-employees (third parties) who may come on-site. As a company, Hazards Ltd has legal personality; but it is run by people, and if the inadequate lighting and slack housekeeping were attributable to the personal neglect of a senior officer (s. 37 HSWA), as well as the company being prosecuted, so too might the senior officer.

1.1.4 Legal issues of the incident

The preceding paragraphs show that it is necessary to consider:

• Criminal and civil law;

• The organisation of the courts and court procedure;

• Procedure in employment tribunals;

• The legal authorities for safety law: legislation and court decisions.

1.1.5 Criminal and civil law

A crime is an offence against the state. Accordingly, in England prosecutions are the responsibility of the Crown Prosecution Service; or, where statute allows, an official such as a factory inspector (ss. 38, 39 HSWA). Very rarely may a private person prosecute. In Scotland the police do not prosecute, since that responsibility lies with the Procurators Fiscal, and ultimately with the Lord Advocate. In Northern Ireland the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) initiates prosecutions for more serious offences, and the police for minor cases. The DPP may also conduct prosecutions on behalf of government departments in magistrates’ courts when requested to do so. The Procurators Fiscal, and in England and Northern Ireland the Attorney General acting on behalf of the Crown, may discontinue proceedings; an individual cannot. The Justice (Northern Ireland) Act1 provides for a Prosecution Service to undertake all prosecutions and for the DPP to discontinue proceedings, not the Attorney General (see also section 1.1.14).

Criminal cases in England are heard in the magistrates’ courts and in the Crown Court; in Scotland mostly in the Sheriff Courts, and in the High Court of Justiciary. In Northern Ireland criminal cases are tried in magistrates’ courts and in the Crown Court. In all three countries the more serious criminal cases are heard before a jury, except in Northern Ireland for scheduled offences under the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act of 1996.

The burden of proving a criminal charge is on the prosecution; and it must be proved beyond reasonable doubt. However, if, after the incident at Hazards, Instepp prosecutes, alleging breach of, say s. 2 of HSWA, then Hazards must show that it was not reasonably practicable for the company to do more than it did to comply (s. 40 HSWA). This section puts the burden on the accused to prove, on the balance of probabilities, that he had complied with a practicable or reasonably practicable statutory duty under HSWA.

The rules of evidence are stricter in criminal cases, so as to protect the accused. Only exceptionally is hearsay evidence admissible. In Scotland the requirement of corroboration is stricter than in English law.

The main sanctions of a criminal court are imprisonment and fines. The sanctions are intended as a punishment, to deter and to reform, but not to compensate an injured party. A magistrates’ court may order compensation to an individual to cover personal injury and damage to property. Such a compensation order is not possible for dependants of the deceased in consequence of his death. At present the upper limit for compensation in the magistrates’ court is £5000.2

A civil action is between individuals. One individual initiates proceedings against another and may later decide to settle out of court. Over 90 per cent of accident claims are settled in this way.

English courts hearing civil actions are the county courts and the High Court; in Scotland the Sheriff Courts and the Court of Session. In Northern Ireland the County Courts and the High Court deal with civil accident claims. Civil cases rarely have a jury; and in personal injury cases only in the most exceptional circumstances.

A civil case must be proved on the balance of probabilities, which has been described as ‘a reasonable degree of probability … more probable than not’. This is a lower standard than the criminal one of beyond reasonable doubt, which a judge may explain to a jury as ‘satisfied so that you are sure’ of the guilt of the accused.

In civil actions the claimant, formerly the plaintiff (the pursuer in Scotland), sues the defendant (the defender) for remedies beneficial to him. Often the remedy sought will be damages – that is, financial compensation. Another remedy is an injunction, for example, to prevent a factory from committing a noise or pollutant nuisance.

1.1.6 Branches of law

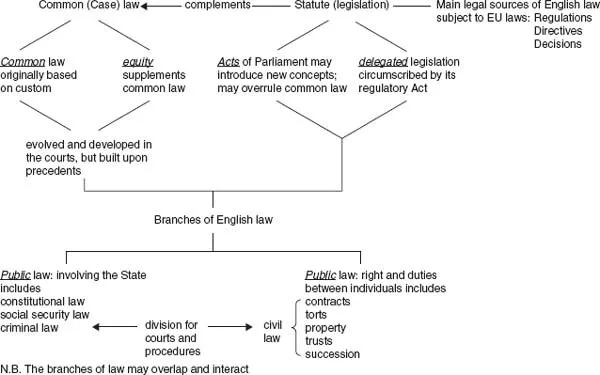

As English law developed it followed a number of different routes or branches. The diagram in Figure 1.1.1 illustrates the main legal sources and some of the branches of English law.

Criminal law is one part of public law. Other branches of public law are constitutional and administrative law, which include the organisation and jurisdiction of the courts and tribunals, and the process of legislation.

Civil law has a number of branches. Most relevant to this book are contract, tort (delict in Scotland) and labour law. A contract is an agreement between parties which is enforceable at law. Most commercial law (for example, insurance) has a basis in contract. A tort is a breach of duty imposed by law and is often called a civil wrong. The two most frequently heard-of torts are nuisance and trespass. However, the two most relevant to safety law are the torts of negligence and of breach of statutory duty.

Figure 1.1.1 Sources and branches of English law

The various branches of law may overlap and interact. At Hazards, Bertha has a contract of employment with her employer, as has every employee and employer. An important implied term of such contracts is that an employer should take reasonable care for the safety of employees. If Bertha proves that Hazards were in breach of that duty, and that in consequence she suffered injury, Hazards will be liable in the tort of negligence. There could be potential criminal liability under HSWA. Again, Hazards may discipline a foreman, or Bertha’s workmates may refuse to work in the conditions, taking the situation into the field of industrial relations law.

1.1.7 Law and fact

It is sometimes necessary to distinguish between questions of law and questions of fact.

A jury will decide only questions of fact. Questions of fact are about events or the state of affairs and may be proved by evidence. Questions of law seek to discover what the law is, and are determined by legal argument. Ho...