- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Environmental illness: certain health professionals and clinical ecologists claim it impacts and inhibits 15 percent of the population. Its afflicted are led to believe environmental illness (EI) originates with food, chemicals, and other stimuli in their surroundings -as advocates call for drastic measures to remedy the situation.

What if relief proves elusive-and the patient is sent on a course of ongoing, costly and ineffective ""treatment""?

Several hundred individuals who believed they were suffering from EI have been evaluated or treated by Herman Staudenmayer since the 1970s. Staudenmayer believed the symptoms harming his patients actually had psychophysiological origins-based more in fear of a hostile world than any suspected toxins contained in the environment.

Staudenmayer's years of research, clinical work-and successful care-are now summarized in Environmental Illness: Myth & Reality. Dismissing much of the information that has attempted to defend EI and its culture of victimization, Staudenmayer details the alternative diagnoses and treatments that have helped patients recognize their true conditions-and finally overcome them, often after years of prolonged suffering.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

chapter one

What is “environmental illness”?

The subject of this book has many names. Whenever a phenomenon is called so many things one can be sure that none describes it very well. Some say it is so mysterious that its essence cannot be conceived, much less defined. Its effects are said to be powerfully harmful. There is consensus that it has significant impact on our society. It has ramifications for science, medicine, social attitudes, the media, insurance coverage, regulatory policy, legislation, civil litigation, disability and entitlement programs, politics, and, last but not least, the individuals said to suffer from it. Yet,

• We don’t know what to call it.

• It can’t be defined.

• It can’t be diagnosed.

• Responsible scientific disciplines tells us it does not qualify as a disease or as a syndrome.

• It has no consistently identified biological mechanism of action.

• It is based on toxicologic and physiologic rationale that is implausible.

• It is inconsistent with the laws of chemistry and physics.

For these reasons, it is best to think of “environmental illness” as a phenomenon rather than a disease.

I begin this chapter by contrasting environmental illness with well-characterized, chemically induced diseases. Second, I define some of the concepts of environmental illness (EI) and the parties who advocate environmental illness as a toxicogenic theory, meaning that ill-health effects are caused by environmental exposures to chemicals at levels tolerated by most of the population. Third, I describe the characteristics of patient symptoms, all of which need to be explained. And, fourth, the remainder of the chapter is a brief outline of the two opposing theories — toxicogenic and psychogenic — highlighting the issues to be addressed in later chapters of the book.

What it is not

Historically, the effects of chemicals on disease and particularly the functioning of the nervous system are firmly rooted in antiquity and are universally accepted tenets of modern medical practice. The clearest example in medicine is the Physician’s Desk Reference of drugs, which is an encyclopedia of the healing as well as the adverse side effects that can be caused by medicines prescribed by physicians. The mortality and associated costs related to adverse drug events in the U.S. are greater than that of motor vehicle injuries, assaults with firearms, and AIDS combined. According to Multum Information Services (Denver, CO), 19% of medical treatments are associated with adverse drug events, which cause 11% of all hospitalizations and account for 60,000 to 140,000 inpatient fatalities per year.

There is no question that illness related to chemicals in the environment can be produced by toxicologic as well as immunologic mechanisms. A variety of physical factors, infection, or direct toxic or pharmacologic effects of assorted natural and synthetic substances can do the same. Generally, these diseases present with characteristic symptoms and physical and laboratory findings, as well as a definable pathology. One example is the causal link between ingestion of alfalfa seeds and symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Selner and Condemi, 1988). A second example is the causal link between contaminated rapeseed oil and an epidemic of scleroderma-like syndrome that erupted in Spain in 1981, affecting close to 20,000 people (Lopez-Ibor et al., 1985). Death and respiratory disorders were sobering consequences in the methyl isocyanate chemical spill in Bhopal, India (Murthy and Isaac, 1987). And, possibly the worse technological disaster was the nuclear radiation accident at Chernobyl, Ukraine, which killed instantly, caused terminal cancer and chronic diseases, contaminated the region, and created an anxiety throughout Europe.

Specialists in the fields of allergy and immunology, endocrinology, occupational and environmental medicine, pulmonary medicine, toxicology and pharmacology, neurology, and neurotoxicology have demonstrated adverse effects associated with exposure to many chemicals in well-documented, critically reviewed scientific publications (Third Task Force for Research Planning in Environmental Health Science, 1984; Gammage and Kaye, 1985; Frank et al., 1985; Wallace et al. 1987; National Research Council, 1992b; U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, 1992; Spencer and Schaumburg, 1980,1985; Schaumburg and Spencer, 1987; Dybing et al., 1996; Tsien and Spector, 1997). In our laboratory, we have identified individuals who have consistent adverse responses to provocation challenges with low levels of chemicals, illustrated by the following case.

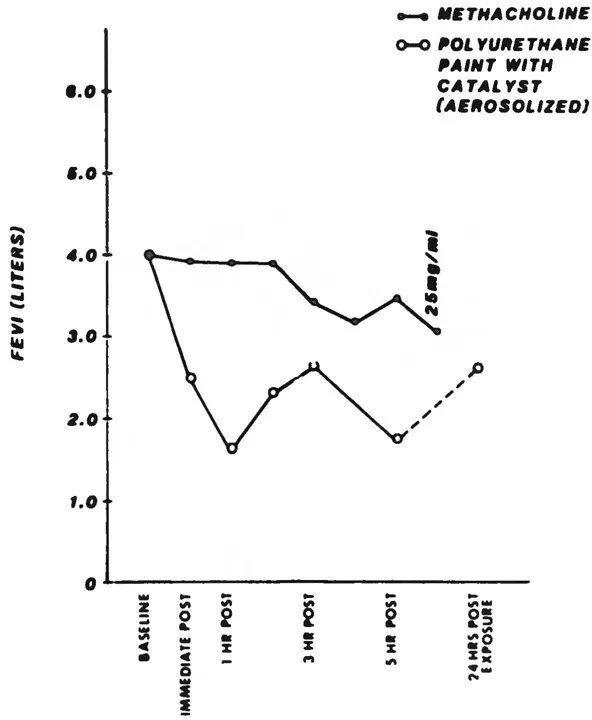

A 53-year-old male aircraft painter complained of respiratory symptoms characterized by bronchospasm on exposure to fumes generated by spray painting. Despite the use of a respirator, he would experience tightness of the chest and wheezing within 30 minutes of exposure to paint fumes. His symptoms cleared on weekends or prolonged holidays, only to recur when he was re-exposed at the workplace. Inhalation challenge testing with methacholine to rule out reversible airway disease was inconclusive, with a drop in FEV1 of 15% (Figure 1.1) occurring only at high doses (25mg/ml). These results suggested that observable respiratory effects attributable to paints could be due to something more than the irritant effect. A simple provocation procedure employing aerosol polyurethane paint and isocyanate hardening accelerators used in the workplace resulted in bronchospasm, as measured by pulmonary functions, with a drop in FEV1 of more than 50% soon after exposure. Because the exposure involved a suspected chemical from the workplace and the challenge demonstrated objective pulmonary changes corroborating symptom complaints, no further evaluation was required. Avoidance options were explored in a harmonious arbitration of the patient’s disability status (Selner and Staudenmayer, 1985).

Figure 1.1 Closed circles indicate methacholine challenges at five inhalations each dose, with 3-minute intervals between doses. Dose sequence: placebo, 0.07, 0.31, 1.25, 5.0, 25.0 mg/mL. (From Selner, J.C. and Staudenmayer, H., Ann. Allergy, 55(5), 665–673,1985. With permission.)

To someone unfamiliar with the current usage of the term “environmental illness”, it could mean a host of chemically related diseases resulting from well-characterized, high-level environmental exposures that have toxicogenic ill-health effects and associated emotional sequelae, such as those just presented. This example is presented to emphasize what this book is not about. The subject of this book is much more difficult to define.

Examples of what it is

The 1973 Arab oil embargo impacted environmental illness. To conserve energy for heating and cooling, large buildings were designed to be air-tight, and the rates of air exchange were reduced through alterations in heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems. Because of these design and engineering changes, the quality of indoor air was affected and some people fell ill. These effects are called building-related illness, defined as being an objective disease or discomfort caused by identifiable agents in the building such as excessive carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide, inappropriate lighting, or allergens such as molds, pollens, and others which proliferate or are trapped in the accumulation of moisture or dust (Bardana and Montanaro, 1997). In contrast to building-related illness, the term “sick building syndrome” was coined as an opportunistic expression which did not require objective indices of disease, nor exposure to measurable levels of chemicals or allergens that exceed some toxicologic standard. Initial speculation focused on the quality of “stale air”, but buildings with documented poor air circulation, as measured by comparative carbon dioxide concentrations, were found to be unrelated to symptom complaints.

One double-blind study in Canada tested the hypothesis that symptoms were associated with the accumulation of contaminants resulting from reduced supply of outdoor air (Menzies et al., 1993). The study involved 1546 workers in four buildings. Unknown to the workers, the ventilation systems were manipulated to deliver varying amounts of outdoor air (7 and 32%) for one-week periods, randomly counterbalanced over consecutive weeks. Each week the workers rated their symptoms. There were no differences in the symptom ratings associated with the amount of outdoor air flow, even when corrected for work-site manipulations of ventilation, temperature, humidity, and air velocity. The investigators concluded that the supply of outdoor air did not appear to affect workers’ perception of their office environment or their reporting of symptoms considered to be typical of the “sick building syndrome”.

Furthermore, “sick building syndrome” could occur in buildings that were built before 1973 and did not have the airtight design or decreased air-exchange rate. This led to alternative hypotheses about other chemicals being the toxic culprits (Kreiss, 1993); however, studies showed that symptoms did not correlate with measurements of indoor air levels of particulates, volatile organic compounds, and specific chemicals such as formaldehyde (Hodgson et al., 1991).

The purported causes of “sick building syndrome” include anything that can be found in buildings, even agents that go beyond chemicals. For example, electromagnetic force (EMF) fields are postulated to affect body polarity adversely. These EMF fields may emanate not only from inanimate electrical sources such as power lines, heating blankets, televisions, or computer visual display units, but also from another person. Each person is said to have unique EMF fields which may be incompatible with those of another person such that one individual can induce a reaction in the other if they come into close proximity.

It appears that there is more to “sick building syndrome” than the 1973 oil embargo. Several studies have shown that social and organizational factors in the workplace offer the most probable explanation of “sick building syndrome” (Baker, 1989; Hedge, 1995; Ryan and Morrow, 1992).

With apprehension, the next environmental manifestation of environmental illness was awaited. The wait was not long, and the most recent manifestation was ironically also related to the Mideastern oil politics resulting in the Persian Gulf War. Veterans who participated in Desert Shield, Desert Storm, and the peacekeeping afterwards began complaining of a mysterious illness that has been labeled “Gulf War Syndrome” and is officially referred to as Gulf War Veterans’ Illnesses by the Presidential Advisory Committee. Not only were the veterans deployed in the Gulf affected, but also their family members with whom they had contact after returning to the U.S. To date, after extensive investigation, no evidence of a toxicologic effect has been demonstrated, while numerous toxicogenic theories have been disproved (Lashof, 1996).

Table 1.1 Some Labels Applied to the EI Phenomenon

Aircraft workers’ syndrome | Gulf War syndrome |

Allergic toxemia | Multiple chemical sensitivity |

Cerebral allergy | Multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome |

Chemical AIDS | Sick building syndrome |

Chemical allergy/sensitivity | Total allergy syndrome |

Chemical hypersensitivity syndrome | Toxic carpet syndrome |

Chemically induced immune dysregulation syndrome | Toxic-induced loss of tolerance |

Total environmental allergy | |

Chemical intolerance | Total immune disorder syndrome |

Ecologic illness | Toxic encephalopathy |

Environmental hypersensitivity | Toxic response syndrome |

Environmental illness | Toxicant-induced loss of tolerance |

Environmental irritant syndrome | 20th-century disease |

Environmental maladaption syndrome | Universal allergy |

Generalized immune deficiency | Universal reactivity, universal reactors |

Definitions

Naming the indefinable

If one conception does not differ practically from a second, then acceptance of it adds nothing to our acceptance of that second conception; and if it has no assignable practical effects whatsoever, then the works that express it are so much meaningless verbiage.

C.S.Peirce’s Philosophy of Pragmatism (see Gallie, 1952)

A seemingly endless list of synonyms for this phenomenon has come into our vocabulary (Table 1.1). The most common labels are environmental illness, ecologic illness, chemical sensitivities, and multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS).

The label “multiple chemical sensitivity” was coined by Cullen for the purpose of identifying a population to study experimentally and is defined as (Cullen, 1987):

An acquired disorder characterized by recurrent symptoms, referable to multiple organ systems, occurring in response to demonstrable exposure to many chemically unrelated compounds at doses far below those established in the general population to cause harmful effects. No single widely accepted test of physiologic function can be shown to correlate with symptoms.

Table 1.2 summarizes the seven criteria Cullen proposed to establish the diagnosis. The MCS diagnostic criteria are inclusive, and they define sufficiency. MCS casts a broad net which fails to exclude individuals whose symptoms are explained by alternative, well-established diagnoses. In statistical terms, these criteria have sensitivity (minimizing the likelihood of missing someone), but lack specificity (inclusion of non-cases). For example, cases that are explained by psychiatric or psychological conditions need not be excluded. Another limitation is the lack of operational definition of certain terms, leaving them open to interpretation and theoretical speculation. What is a documentable exposure? What is the association between exposure and harm? Is self-report sufficient to establish either? What are predictable stimuli? When are exposures demonstrable? If several people testify to the presence of an offending age...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- 1 What is “environmental illness”?

- 2 Toxicogenic theory

- 3 Unsubstantiated diagnoses and treatments

- 4 Studies supporting the psychogenic theory

- 5 Assessment of the toxicogenic research program

- 6 Psychogenic theory

- 7 Placebo and somatization

- 8 Learned sensitivity

- 9 The stress-response

- 10 Panic attacks and anxiety disorders

- 11 Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder

- 12 The limbic system and trauma

- 13 Personality disorders

- 14 Iatrogenic illness: exploitation and harm

- 15 Treatment

- 16 Politics

- 17 Future directions

- Appendix A. A methodology of scientific research programs

- Appendix B. Court rulings unfavorable to environmental illness

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Environmental Illness by Herman Staudenmayer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.