eBook - ePub

Architecture of Regionalism in the Age of Globalization

Peaks and Valleys in the Flat World

This is a test

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architecture of Regionalism in the Age of Globalization

Peaks and Valleys in the Flat World

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The definitive introductory book on the theory and history of regionalist architecture in the context of globalization, this text addresses issues of identity, community, and sustainability along with a selection of the most outstanding examples of design from all over the world.

Alex Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre give a readable, vivid, scholarly account of this major conflict as it relates to the design of the human-made environment. Demystifying the reasons behind how globalization enabled creativity and brought about unprecedented wealth but also produced new wastefulness and ecological destruction, the book also looks at how regionalism has also tended to confine, tearing apart societies and promoting destructive consumerist tourism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Architecture of Regionalism in the Age of Globalization by Liane Lefaivre, Alexander Tzonis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architektur & Architektur Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Regional and the Classical Imperial

The question of ‘regional’ architecture – its environmental aspects and its political implications, hot topics today in the context of triumphant globalization – appears, probably for the first time in history, in a Roman text, De Re Architectura, written in the time of Augustus (63 BCE – 14 CE), the first Roman emperor. The text identifies ‘regional’ buildings and juxtaposes them with those of Greece and Rome which we call today ‘classical’, a word not used by Vitruvius.

Vitruvius dedicated his book to the imperator, Supreme Ruler, Caesar, named Augustus because he ‘gained the empire of the world’, praising Augustus because ‘Rome gloried in [his] triumph and victory’, but also because of his support for the construction of public buildings in Rome. In the words of the Roman historian Suetonius, Augustus ‘found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble’.

De Re Architectura is the best written source we have on the architecture of antiquity. From what we know and from the tone of his book, Vitruvius aspired to be among the leading Roman intellectuals of his time busy constructing a political theory and a Roman identity as global imperial ruler. It is clear, therefore, that Vitruvius's goal in writing his book was practical and pressing: the new empire needed a universal toolbox of design and construction rules capable of serving a huge-scale construction program alongside the universal economic, legal, and cultural ones, establishing a centralized global order that was taking the first major step toward making the world flat.

The book tried to cover almost all aspects of design, from buildings and cities to machines and fortifications, with references to philosophy, natural science, astronomy, ‘physiology’, acoustics, and medicine. Vitruvius was an engineer, architect, and writer, who was trying to cover all these topics in the framework of the philosophy of Lucretius. Accordingly, he believed that architectural form is determined by natural causes. What cannot happen in nature, he wrote, cannot be forced in an artifact. In the fourth book of his text, he declared his intention to reduce architectural knowledge to ‘a perfect order’ (perfectam ordinationem), a universal rule system within which nothing was permitted to be ‘inchoate’ and everything was to follow rationally (habet rationem). In this spirit, he presented Greco-Roman architecture and its ‘kinds’ (he called them genera, in the Aristotelian sense of natural kinds) – Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian – their ‘parts’, their ‘members’, and their organization in terms proportion and symmetry. Then he turned to another ‘kind’ of building, not subject to the same rules, regional architecture.

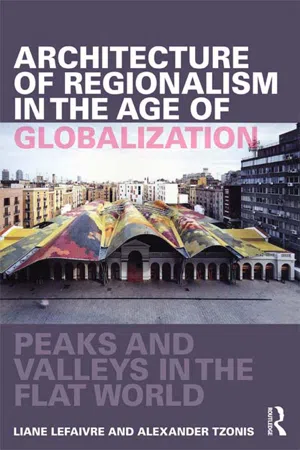

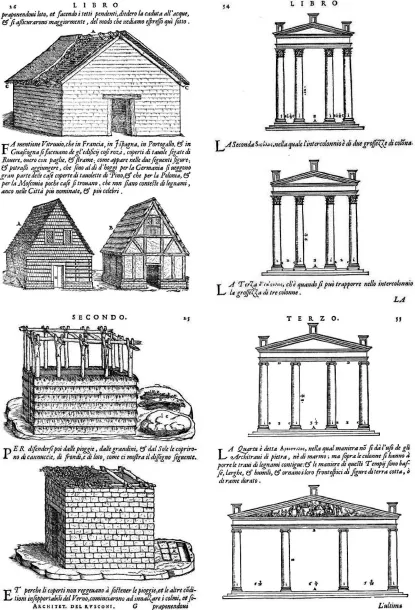

Figure 1.01 Four regional houses and four classical temples. Illustration for Vitruvius's text in Giovan Antonio Rusconi's Dell'architettura (1590).

As a rationalist, after classifying the kinds and describing their differences, Vitruvius tried to explain what made them different. He contrasted the ‘regional’ ‘kinds’ of buildings (genera aedificiorum), the ones that belong to a region (regionum), with the Greek and Roman ones, their diversity caused by their different characteristics ‘ordained by Nature’ (‘proprietates locorum ab natura rerum … constituere aedificiorum qualitates’). In other words, the physical environment of the regions the buildings belong to accounts for their variety. The theory is not original. It goes at least as far back as a treatise by Hippocrates (460 BCE – 370 BCE), On Airs, Waters, and Places, a text that deals with the relation between humankind and the environment.

It is of particular interest that, in addition to architectural issues, Vitruvius also discusses the political implications of a world divided into regions of unequal quality. Thus, just as climate and physical conditions influence buildings, so do they shape human beings. Consequently, he claimed, just as the extreme physical conditions (natura rerum) of the North dictate buildings with strongly sloping roofs, among other features, and at the opposite extreme the physical conditions of the South lead to buildings with almost flat roofs, so these extreme environmental conditions create extremely different kinds of people, different in physical constitution and in behavior.

On the other hand, Vitruvius argued, there is a ‘temperate’ environment that produces temperate architecture and temperate people. This is the environment Romans inhabit and the architecture they build. The temperate environment is superior to the extreme ones, and so it is with the temperate buildings and people. The temperate architecture and people are more balanced, reflecting the balanced environmental characteristics of the region they inhabit. Again, elements of this theory are to be found in The Histories of Herodotus, where he argues that the climate of Greece is ‘ideal’, being temperate, in contrast to the very cold climate of Scythia and the very hot one of Egypt. Similarly, the Hippocratic treatise claimed that Europeans are more industrious than Asians, owing to the temperate climate of their region.

From these observations, Vitruvius draws a political conclusion arguing that because of their temperate region (temperatamque regionem), the Romans have special courage and strength and for this reason they can overcome the deficiencies of the people of the northern or southern regions, presumably Germans and Africans. Romans are allocated this ‘excellent and temperate region in order to rule the world’ (terrarium imperii). Interestingly, the Hippocratic treatise argued in addition that because of their environment and climate, Europeans do not depend on any despotic authority, whereas Asians are governed by despots (chaps. 14–22).

The architectural implications of this environmental-political theory were that, by Nature, Roman (‘classical’) architecture must be applied globally. It is obvious that Vitruvius's reasoning was inconsistent. On the one hand, from nature (naturae deducta) and on the basis of rationality (disciplinae rationes), it asserted that buildings, like people, are adapted to the environment of their regions, resulting in regional variety and diversity; on the other, it supported the political, ‘imperial’, universal normative doctrine that Roman (‘classical’) buildings, like the ruling Romans, ought to be imposed in a region without being adapted to its regional conditions, thereby creating a standard, classical, global world. History might have helped Vitruvius to understand that even classical Greco-Roman architecture was not universal and that its buildings were the result of regional adaptations. History occupies a small place in the De Re Architectura and it is frequently impressionistic even by the standards of its time.

In the years to come, Vitruvius's materialist theory of regional architecture would survive, associated with the role of architecture in shaping ethnic identity, and it would also live on incarnated in racist and chauvinistic theories in nineteenth-century or early-twentieth-century architecture. But it will also serve as a point of departure in the study of the relation between particular environmental climatic factors and the regional diversity of human habitat and the regionalist movements toward its achievement.

In contrast to Vitruvius's book, Plutarch's On Music, written soon after De Re Architectura, gives a detailed historical account of armoniai, ‘modes’, tonal scales, the ‘kinds’ of music used in antiquity, and the role of imports, originally Asian, Thracian, and Egyptian, that led to the Greek inventions. Vitruvius's discussion about the origin of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian kinds of architecture was brief, anecdotic, or fairy-tale-like. However, there is evidence from the great Greek historian Herodotus, who credited non-Greeks with the origin of most Greek achievements, that many key aspects of Greek architecture in fact came from other regions. Paradoxically, Herodotus was attacked by Plutarch, who called him ‘friend of the barbarians’,1 even though Plutarch himself, as mentioned, was equally forthright in attributing to non-Greeks the origins of Greek music.

The Alleged Purity of the Classical

The question of whether Greco-Roman architecture was original, pure, and spontaneous as opposed to created through ‘borrowings’ became very important, as we will see later, in the context of nineteenth-and twentieth-century debates about whether the pure ethnic ancestry of some regionalist groups gave them the nationalist right to become legitimate states and the imperialist right to conquer territories and take control of other groups.2

In these debates, it was repeatedly claimed that Greek architecture and the classical tradition were the original and pure expression of a special kind of people, the Aryans, who had their origins in a special region of the North. The contemporary implications of this story were that Greek architecture and culture, on which Western architecture and culture were founded, were pure and unadulterated. We find this view, for example, expressed as late as 1940 by the prominent Talbot Hamlin3 in describing the creation of classical architecture as resulting from the coming together of a people ‘speaking a language which belongs to the Aryan linguistic group, that … were blond … Ionians and … Dorians’ and that they ‘created the Ionic and Doric orders’. The notion of Aryan purity is combined with Aryan superiority in January 1943, when a German Nazi philosopher, Martin Heidegger, anxious about ‘the planet in flames’ as a result of the world war, compares the noble mission of Germany with that of ancient Greece, both being races ‘of poets and thinkers’ dedicated to ‘saving the West’.4

The Impure Regional Roots of Greek Classical Architecture

In fact, Greek classical architecture is anything but pure. It is an amalgam of different regional architectures, as we will see in the rest of this chapter.

There is a mass of evidence that Greek architecture, like most expressions of Greek culture, was not the product of the genius of a single people working in isolation. The Greeks and before them the Minoans were part of the early Mediterranean world. They settled next to the sea and established long-range sea routes interlinking diverse coastal regions, distributed over regions in the ‘water-washed islands’ or on the coasts of the wine-dark sea (oinopi ponto), crossing it in ‘deep blue-bow’, ‘black hollow ships’, enabling widely spread communities to stay closely interlinked, weaving almost global networks that enabled the exchange of food, materials, artifacts, people, techniques, information.

Homer, one of the great architects of the Greek identity, in The Odyssey [XVII380] refers to carpenters and builders as men with a craft from several regions traveling ‘all over the boundless earth’ rather than sitting in one place. Aristotle also considered it normal that craftsmen were mobile, thus most of the time immigrants and not citizens. As their names reveal, the great potters and vase painters of Athens were foreign. Rather than worrying about purity and authenticity, the ancient Greeks consistently welcomed regional materials, appropriating them and recombining them into universal systems. Even their dodecatheon, the family of deities of Greek polytheism, had its origins in regions outside Greece, the Greeks importing the deities and fitting them into a system, a constructed conceptual framework through which they conceived and construed their physical, cultural, and social world.5

As we shall see, Greeks settled close to the sea and set up ‘global’ (for their time) communication networks, interconnecting diverse coastal regions of the Mediterranean, interacting with them, conquering them, and trading with them and, as a result, flattening the world. The unique characteristics of the ‘Greek miracle’ were exploration, discovery, recruitment, systematization, transformation, invention, through redesign and synthesis.

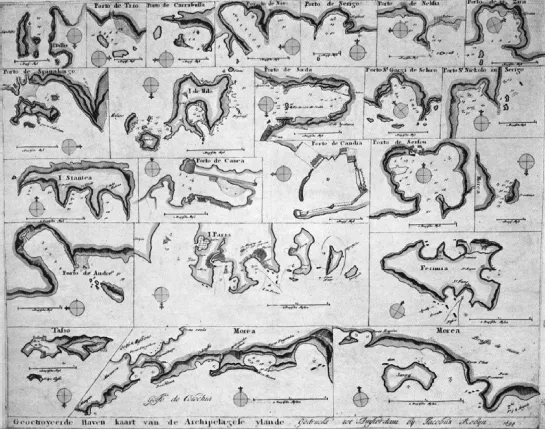

Figure 1.02 Protected bays in the Mediterranean: ‘Archipelago’ by Jacobus Robyn (Amsterdam, 1694).

Between roughly 2000 and 1100 BCE, the area of what today is southern Greece possessed important settlements, densely built centers, inhabited by the so-called Minoans and Mycenaeans. Long-range sea routes linked their settlements, supplying food of higher nutritional value, superior construction materials and technology, artifacts, people, and information. In particular, the elements of novel knowledge imported from abroad recombined through ‘fission and fusion’ led to inventions that enabled a rise in the quality of the inhabited environment, constructing a built tissue with larger and more regularly configured spaces, and impressive domed burial structures. Painting was advanced, writing had become established, and the Mediterranean world was becoming increasingly flat.

Then, at around 1100, most of that social and cultural development vanished and was replaced by what has been called a Dark Age. For unknown reasons (although one of the contributing factors was the arrival of a new group, the Dorians), the densely populated ‘urban’, built centers were deurbanized, being replaced by distributed ‘tribal’ hamlets revealing a less structured, loosely coordinated society, and a lower level of division of labor. Writing was forgotten and significant knowledge, including sophisticated knowledge of design and construction techniques that we found practiced by Minoans and Mycenaeans, their maritime networks linking them with other Mediterranean regions, faded away.

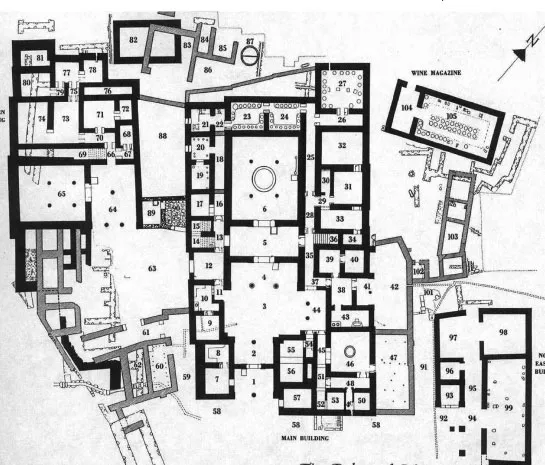

Figure 1.03 Acropolis of Pylos, c.1300.

The new Dark Age perhaps was not as dark as was once believed, but its settlements consisted mainly of communities turned inward on themselves, and the world of southern Greece entered a new phase of regional ‘deglobalization’.6

Nevertheless, despite these prevailing conditions, after a period of about three centuries, for obscure reasons again (some experts suggest improvements in agricultural te...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustration credits

- Preface: The Never-Ending Challenge of Regionalism

- Introduction: The End of Geography?

- 1. The Regional and the Classical Imperial

- 2. The First Regionalist Building-Manifesto

- 3. A Flat Archipelago of Garden-Villas

- 4. ‘Consult the Genius of the Place in All’

- 5. From the Decorated Farm to the Rise of Nationalist Regionalism

- 6. From Regions to Nation

- 7. Gothic Communalism and Nationalist Regionalism

- 8. Homelands, World Fairs, Living-Spaces, and the Regional Cottage

- 9. International Style versus Regionalism

- 10. Regionalism Rising

- 11. Regionalism Redefined

- 12. Regionalism Now

- Coda

- Notes

- Index