![]()

1

The organic crisis of British capitalism and race: the experience of the seventies

John Solomos, Bob Findlay, Simon Jones and Paul Gilroy

We are witnessing and passively acquiescing in a quiet but hardly bloodless revolution. The induction of general social disorder, uncensored crime and personal negligence have replaced more warlike conduct as the painless way to undermine the stability of the state.

JAMES ANDERTON

The combined assault on English identity and values is neither planned nor fully understood by its participants; its roots often lie deep in the unconscious. Its main force stems from the lack of coherent opposition. Too many people are frightened off by accusations: ‘racialist’, ‘elitist’ or simply ‘old-fashioned’, which make cowards of nearly all.

ALFRED SHERMAN

Introduction

The central theme of this book is that the construction of an authoritarian state in Britain is fundamentally intertwined with the elaboration of popular racism in the 1970s.1 * The aim of this introductory chapter is more modest. It offers a framework for examining the relation of ‘race’ to British decline, and attempts a periodization of state racism during the seventies. We hope to provide a more detailed morphology of these transformations in future work.2

The parallel growth of repressive state structures and new racisms has to be located in a non-reductionist manner, within the dynamics of both the international crisis of the capitalist world economy, and the deep-seated structural crisis of the British social formation. This idea links the various chapters which follow. Some aspects of it have already been developed by others,3 but the argument is far from complete. What concerns us, therefore, is not to outline a theory of racist ideologies, but to scrutinize the political practices which developed around the issue of race during the seventies. We have chosen this approach for two basic reasons. First, we believe that it is not possible to understand the complex ways in which state racism works in British society without looking closely at the ways in which it is reproduced inside and outside state apparatuses. Second, we feel that it is not possible to see racism as a unitary fixed principle which remains the same in different historical conjunctures. Such a static view, which is common in many sociological approaches, cannot explain how racism is a contradictory phenomenon which is constantly transformed, along with the wider political-economic structures and relations of the social formation.4

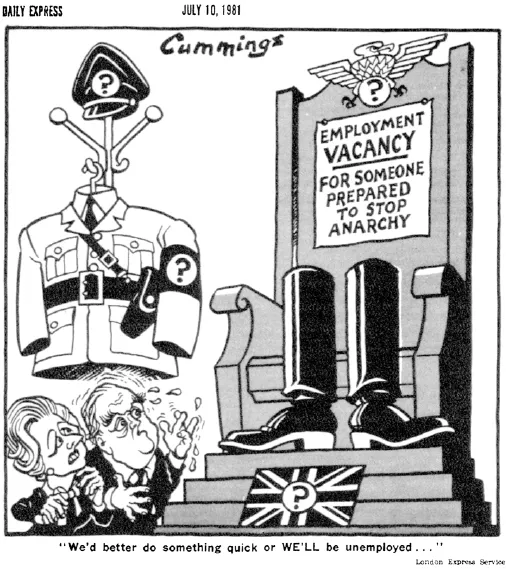

Source: Daily Express, 10 July 1981

Reproduced by permission of Daily Express

The function of this chapter is twofold—first, to introduce at a more general, and therefore theoretical level, themes which will be covered later on, and second, to explain the way in which certain key concepts have been used. In the second and third sections we shall attempt to analyse, albeit briefly and schematically, some of the main shifts in the relation between the various types of state intervention and the wider organic crisis. Although a number of recent Marxist studies have analysed the deep economic roots of the present crisis, we think that this is only part of the story. This is why we emphasize the organic nature of the crisis, meaning by this that it is the result of the combined effect of economic, political, ideological and cultural processes. A full historical account of these issues has not been attempted in this book, partly because we feel that this is one area where the recent revival of Marxist political economy has made a substantive contribution.5 Nevertheless, as a contribution to this debate, we will introduce some discussion of race around which a fuller historical account may be constructed. In the fourth and fifth sections we attempt to show how official thinking on violence, law and order, and race has been closely connected. We establish the origins of these interconnections in debates about violence which began in the sixties and argue that they have assumed a particularly sharp and pernicious form during the seventies. This is because race has increasingly become one of the means through which hegemonic relations are secured in a period of structural crisis management. Although as Chapters 2 and 8 emphasize, we see race as a means through which other relations are secured or experienced, this does not mean that we view it as operating merely as a mechanism to express essentially non-racial contradictions and struggles in racial terms. These expressive aspects must be recognized, but race must also be approached in its autonomous effectivity.

Racism as it exists and functions today cannot be treated simply from a sociological perspective: it has to be located historically and in terms of the wider structures and relations of British society. The historical roots of racist practices within the British state, the British dominant classes, and the ‘British’ working class, go deep and cannot be reduced to simple ideological phenomena. They have been conditioned, if not determined, by the historical development of colonial societies which was central to the reproduction of British imperialism.6 This process generated a specific type of ‘nationalism’ pertinent in the formation of British classes long before the ‘immigration’ issue became a central aspect of political discourse.7

We are arguing for a conception of racism which is historical rather than sociological. Just as Marxist accounts of the historical links between the specific political structures concentrated in the ‘capitalist state’ and the course of capitalist development have emphasized the dynamic nature of political relations, so we would argue that the links between racism and capitalist development are complex, and conditioned by the specific socio-political circumstances in which they function. We want to emphasize that ethnic and racial forms of domination are shared not by exogenous mechanisms, but by the endogenous political economic forces which are dominant in the specific societies under study.8 It follows from this basic proposition that racial forms of domination do not develop in a linear fashion but are subject to breaks and discontinuities, particularly in periods of crisis which produce qualitative changes in all social relations.

This is how we see the period of the seventies in Britain.

The reorganization of the international division of labour and black workers in Britain

It is important to situate the question of racism in Britain today in a broader international context.9 Although these links are often ignored in studies of ‘race relations’ we refuse to study them at our peril. A recent report from the OECD is worth mentioning in this respect, since it points out in a very clear way the need for ‘supporting policies’ to be instituted to help out national states facing acute social problems. The message contained in this report was tellingly summarized in a Financial Times leader called ‘Searching for consensus’:

Not only the pre-summit row over U.S. interest rates, but also the eight days of street fighting in London, Liverpool and Manchester, have shown that consensus, whether on the international stage or at home, is becoming in dangerously short supply.10

It should be made clear that what happened in Britain over the period 1979–81 cannot be reduced to some immutable laws of history which apply to every society at every point of time. Such a reduction avoids difficult problems by attributing the type and direction of the changes occurring to an outside force, some inevitable determinant of all social relations. It is as methodologically distant from a critical Marxist account as the liberal-democratic pluralist framework which dominates the research on race relations in Britain.11 In opposition to it, we suggest that while the specific forms of racism which exist in Britain today have been shaped by endogenous political-economic forces, they have also been transformed in ways which can only be understood as the result of the qualitative changes in Britain’s international position over the last three decades.

Although the disarticulation in labour demand and supply in most European countries since 1973–4 has shown how fragile the position of migrant workers really is,12 there is a much longer history of decline which underlies the experience of these workers in the period after 1945. Indeed, from a longer-term perspective ‘the end of the migrant labour boom’13 does not look as surprising as it may have done a few years back.

The reproduction of racial and ethnic divisions has been a central feature of accumulation in the post-war period precisely because of the requirement that labour from the colonies and other peripheral economies be used to reorganize the main industrial sectors of the advanced industrial economies. This is a proposition which has received strong support from a number of historical and sociological studies of specific societies,14 and from a theoretical perspective.15 But it has tended to be used as a mechanical model of explanation, with the assumption that it is applicable to every situation, and therefore very little advance has been made in substantiating historically the variable patterns of absorption and exclusion of migrant labour as they have taken shape in the main European societies. We still have no clear idea of how a ‘historically-concrete and sociologically-specific account of distinctive racial aspects’16 can help us to develop a more critical perspective towards the analysis of racism and its modalities in late capitalism. The elements of such an approach exist in abstract formulations but the process of applying them to concrete situations in an experimental fashion has hardly begun.

Take, for example, recent advances in developing critical accounts of how, in their specific modalities, imperialism, the state and the restructuring of the labour process have shaped the articulation of the different levels of the accumulation process.17 A number of these approaches, notably those of the debate on the state, have been usefully applied to the study of migration and the processes through which the segmentation of the working class takes place. Yet no attempt has been made to link such studies to issues such as racial/ethnic divisions, which have tended to be consigned to the study of ideologies rather than political economy. Because of this neglect, the fleld of race has been dominated by narrow sociological studies, and no grounded attempts to locate it within a political economy framework have materialized.

The reorganization of the international division of labour has only belatedly been analysed from the perspective of its implications for migrant workers, although a number of general accounts of a shift from ‘labour-import’ to ‘capital-export’ strategies have been written.18 Such accounts have, however, not been balanced by a parallel attempt to draw out the mediations between the international environment and the operation of individual nation states. A few illuminating remarks have been made by Stuart Hall,19 Immanuel Wallerstein,20 Sivanandan21 and Marios Nikolinakos.22 But their accounts have tended to remain at too general a level of abstraction to be directly applicable to the contemporary transformations of the politics of migration and ethnic/racial divisions. What they do suggest, however, is the need to apply criteria of historicity and of combined though uneven development to the study of ethnic/racial patterns of domination in late capitalism. Wallerstein, in his historical account of capitalist development, argues correctly that Marxists have too often failed to locate racial, national, or regional divisions materially, and consigned them all too simply to the ubiquitous super-structure. He himself proposes that such divisions are not exogenous but endogenous to the rearticulation of nation and class which capitalist development brought about:

The development of the capitalist world-economy has involved the creation of all the major institutions of the modern world: classes, ethnic/national groups, households, and the ‘state’. All of these structures postdate, not antedate, capitalism; all are a consequence, not cause. Furthermore, these various institutions in fact create each other. Classes, ethnic/national groups and households are defined by the state, and in turn create the state, shape the state and transform the state. It is a structured maelstrom of constant movement, whose parameters are measurable through the repetitive regularities, while the detailed constellations are always unique.23

This conception of the interplay between the state and the reproduction of ethnic/racial differences is important because it situates the operation of the international context within the complex reality of the political and economic forces in each national formation. Moreover it firmly locates the capitalist state as a central mechanism for the articulation and reproduction of such divisions. It thus problematizes both narrow sociological models which take the nation state for granted, and reductionist frameworks which only ‘explain’ race through displacing it on to economic forces. In his work on mugging, and the position of race and class in the Caribbean, Stuart Hall has developed a similar account of how the reproduction of hegemony is not a stable process but is constantly reshaped and undermined by the operation of the wider socio-economic structures.24

It would be against the line of thought developed in this book to think that these general arguments are directly applicable to the complex history of black labour in Britain, both before and after 1948. A number of mediations have to be introduced if we are to analyse how the patterns of ‘inclusion’ and ‘exclusion’ of black workers have been transformed over time. Certainly a global view of labour migration is important if we are to break down the idea that racism is an ‘aberrant epiphenomenon introducing a dysfunction into the regular social order’.25 It is also a means by which one can counter what has been called a loss of historical memory’ and understand the way in which the imperialisms of the past and present secure the transformation of racist practices. According to Stuart Hall the development of racism as a political force has to be understood sui generis:

It’s not helpful to define racism as a ‘natural’ and permanent feature—either of all societies or indeed of a sort of universal ‘human nature’. It’s not a permanent human or social deposit which is simply waiting to be triggered off when the circumstances are right. It has no natural and universal law of development. It does not always assume the same shape. There have been many significantly different racisms—each historically specific and articulated in a different way with the societies in which they appear. Racism is always historically specific in this way, whatever common features it may appear to share with other social phenomena. Though it may draw on the cultural and ideological traces which are deposited in a society by previous historical phases, it always assumes specific forms which arise out of the present—not the past— conditions and organisation of society… The indigenous racism of the 60s and 70s is significantly different, in form and effect, from the racism of the ‘high’ colonial period. It is a racism ‘at home’, not abroad. It is the racism not of a dominant but of a declining social formation.26

This is an argument which will be developed at length, and with reference to concrete issues, later on. But from the perspective of this section it is important to emphasize the issue raised in the last sentence, about the specificity of the sixties and seventies—the period of decline and restructuring. In the context of black settlement in Britain this conceptualization allows us to locate the shaping of racial segmentation in the labour market, residential segregation, legislation to control immigration, and the policing of black working-class areas, as related aspects of organic crisis in the present period. Racisms structure different areas of social life. It is the development of new forms of racism in a phase of relative decline that a materialist analysis of the current situation must explain.

In broad terms, the post-1948 experience of black workers in Britain can be periodized according to three phases: (a) the period of immediate response by the state to the wave of black settlement, leading up to the control of immigration strategy promulgated by the 1962 Act; (b) the articul...