![]()

1 | Social Landlords and Insider–Outsider Theory |

The extent to which social landlords can alleviate the problems of access to housing for poor and disadvantaged people depends primarily on social housing allocation – on who they house. Article L. 441–1 of the Code de la construction et de l’habitation (C.C.H.) provides priority for the disadvantaged in specific allocation rules. These rules will fix:

the general criteria for priority for the allocation of homes, notably in favour of disabled people or families having a dependent in a situation of disability, in favour of people who are poorly housed, disadvantaged or suffering particular housing difficulties for financial reasons or relating to their conditions of existence as well as people in hostels or temporarily housed in transitional establishments and homes.

The major allocation rules and principles are translated in Appendix 1 (p. 257). These were the rules during my study in 2005–6,32 and these rules still echo the right to housing, already quoted,33 but the priority in favour of disadvantaged people was more limited than it first appeared: there were limitations and conflicts with other principles such as property, equality and social mix (more fully described in Chapters 3, 4 and 7), and there were other target populations. There were also conflicts with the interests of the representatives of insiders involved in the allocation process.34 The allocation process itself was difficult and complicated to negotiate.35

Social landlords had strong objectives to construct housing, a policy which in practical terms reduced access to housing for the disadvantaged overall. The law had an accumulation of incentives from successive governments encouraging construction to solve the French housing crisis. Unfortunately, this had effects that included the handing over of control of allocation to local contributing parties, increasing rents, and reduction of cheap housing stock. This incentive structure forced landlords to consider rent returns first and foremost to service construction loans, adversely affecting the candidature of underfunded disadvantaged people, as explained in Chapter 6.

My field study, outlined in Chapter 2, found that many disadvantaged groups had difficulties accessing French social housing, such as single mothers, ethnic minorities, those in financial difficulty and particularly those in hostels. This was at odds with the sentiments expressed in the ‘right to housing’ and the apparent priority in allocation rules.

The institutional and allocation arrangements are explained in general outline in this chapter, introducing the dramatis personnae of local actors and the allocation process. Social housing had its roots in the aftermath of the eighteen and nineteenth century revolutions. French social landlords have a long and honourable record of construction to meet popular housing need, but have faced new challenges in recent years, not least the riots perpetrated by youths in the most deprived estates. The rest of this chapter sets out insider–outsider theory, adapting this labour market theory for housing markets.

This study takes the unambiguous viewpoint that the disadvantaged should be able to find housing somewhere. It does not matter if they are not accommodated in social housing, so long as there are other options, but several interviewees said that French private rented property was also socially exclusionary.

The success of French social landlords might be explained in terms of different purposes, but the objective of housing the disadvantaged attracts national funding and exemptions from EU competition policy, and this is explored in Chapter 2. European interest in social housing means the French debates about allocation policy are of wider interest for harmonization and regulation, including regulation within human rights. The relative effectiveness of the variable models of French social housing allocation thus has more widespread importance.

1.1 Introducing French Social Housing Actors

The application of insider–outsider theory here cannot be properly understood without looking first at what it is applied to. Social landlords were founded in both the UK and France in the second half of the nineteenth century in a broadly similar history. French private social landlords first obtained funding privileges in 1894.36 These social landlords were private limited-profit organizations, ‘companies for good value housing’ or Sociétés d’habitations à bon marché (SAHBMs). A public form of social landlord, the Office public d’HBM (OPHBM), followed from 1912.37 Social landlords were influenced by the UK garden cities movement, which promoted green spaces and urban planning. French thinkers took this up at the beginning of the twentieth century and adapted these ideas to become part of France’s movement for urban design and planning (Magri 1995).

HBM organizations were renamed HLM organizations (habitations à loyer modéré or houses at a moderate rent) in 1950. In 2002, HLM organizations were again rebranded as ‘organismes de l’habitat social’38 (social housing organizations), although they are still ‘HLM organizations’ in legislation. These changes might suggest a problem with their public image related to difficulties in problem estates.39

French HLM organizations have always had an important role as builders. They initially built homes primarily for purchase by workers, and still build homes for sale.40 They had a major role in the post-war reconstruction of France and strategic urban development generally.41 Construction is a strategy to meet housing need, but French construction incentives can impact adversely on the reception of disadvantaged people. An example is how new construction and improvement resulted in increased rents, which were not fully compensated by benefits.42

1.1.1 The Organization of Social Landlords

L’Union sociale de l’habitat (USH) was the umbrella organization for the six main families of HLM organization.43 Only three of these types of organization were important as social landlords in 2005–6, with others generally providing homes for sale. In this book, ‘social landlord’ generally means these three important types of HLM organization.44 There are now 276 public and 281 private social landlords (USH 2010).

During my study, there were two kinds of public HLM organization: the 1912 Office public d’HLM (OPHLM) and the more modern Office public d’aménagement concerté (OPAC) created in 1971.45 There is now only one type of public social landlord (p. 141).

The main private social landlords were the Sociétés anonyme d’HLM (SAHLMs). These were a specially adapted commercial form of company, with severely limited possibilities of distributing profits.46 French housing is rather prone to acronyms, so there is a glossary (p. xi) for when these are used repeatedly. In many cases, acronyms are more commonly used than full names.

1.1.2 Social Landlords’ Social Mission

Despite different detailed rules, public and private social landlords had similar regulation in the C.C.H., and the same allocation principles,47 with priority for disadvantaged people – a public policy orientation confirmed in government literature and research.48

Housing disadvantaged people was not the only objective of social housing, either historically or today. In 1954, social landlords’ longstanding objective of housing workers was changed to add ‘people of little fortune’,49 but the objective of housing workers was not removed until the early 1970s. There was no obligation on social landlords to house the most disadvantaged until relatively recently, when the Geindre report (1990) promoted reform in the loi Besson (Besson Act; see Introduction, p. 1).

French social housing candidates did not have to be poor or needy. Social landlords’ mission at the time included: ‘ … to improve the housing of people on a modest income or the disadvantaged.’50 Those on a ‘modest income’ were generally defined as people within the three lowest income deciles, representing 37 per cent of the population (Ballain 2005). Even above this limit, anyone lawfully resident in France could apply for social housing anywhere in France, provided their income was below income ceilings.51

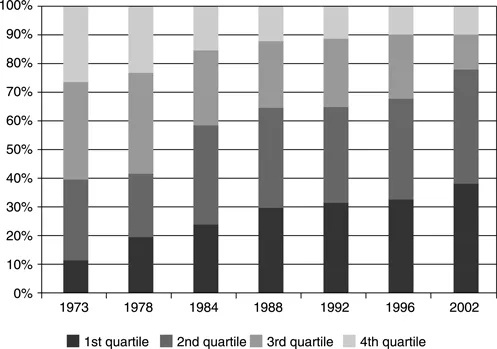

Amzallag and Taffin (2003: 110) said that social landlords housed the poor but did not succeed so well in housing the very poor. In 2002, 37 per cent of social tenants were poor (Figure 1.1). Nonetheless the distribution of social tenants’ incomes shows a continuing presence of better-off households, and a minority of tenants under the bottom quartile of income.

1.1 The income of social tenants 1972–2002. Source: INSEE (2002).

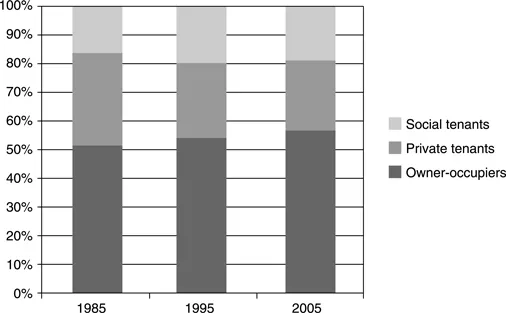

The capacity of French social housing to house the poor also depended on the percentage of social housing stock, as shown in Figure 1.2. Social housing stock declined sharply up to 1995, but then maintained market share up to 2005, when social housing comprised 18.6 per cent of French principal homes. This declined again to 16 per cent of principal homes by 2008 (USH 2009). In practical terms, some of the poor are housed in private rented housing, 24.7 per cent of principal homes. From the 1990s, programmes of tax relief and subsidy encouraged private renting and in 2005–6 there were around two million small private landlords.52 Owner occupancy had steadily increased to 56.6 per cent.

1.2 Housing tenures in France as a percentage of principal homes. Source: EPLS (2005).

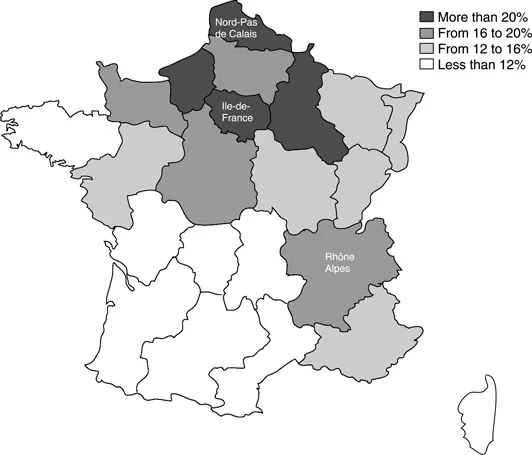

Social housing allocation was also inevitably affected by its uneven distribution across France. Figure 1.3 shows that French social housing was concentrated in particular regions, with more towards the north and east and much less towards the south, so social housing can be sometimes simply unavailable.

1.3 The distribution of social housing in mainland France. Adapted from Direction des Études Financières et Economiques (2005).

Generally statistics and law in this book cover the period of 2005–6, unless it is clear that another period is being discussed, because this is the period of the empirical study, to show how local decision-makers responded to the legislation then current. There will also be comment on later major legal developments. French law changes rapidly, but basic power structures and procedures change much more slowly, so the empirical study is still relevant.

1.1.3 Local Government Involvement

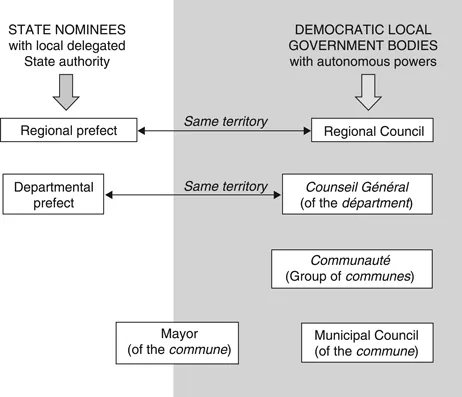

From 1911, local government bodies took the initiative in founding public social landlord companies53 and were still involved in allocation. Consequently, the basic structure of local government should be explained, together with the role of other actors (see Chapter 5 for more detail). Figure 1.4 is a schematic representation of French local government. This has a double structure, being split between elected local bodies, shown on the right-hand side of the diagram, and the nominated local representatives of the central State, shown on the left.

1.4 The main levels of local governance in France.

French local governance was characterized by a multiplicity of local government bodies, each possessing rights or powers affecting housing, although few had significant housing duties. There was fragmentation of powers and budgets, although local actors could act together. Public social landlords could be attached to any level of local government.54 A social landlord might be controlled by one local authority, whilst another one financed its homes elsewhere. During the study, reduced central funding made local authority support indispensible.

The State was primarily responsible for guaranteeing the right to housing for the disadvantaged (see quote on p. 1). The State generally refers to the central state, which also had a local presence through departmental and regional prefects, an old and prestigious office. The prefect was nominated by government and charged with ensuring the legality of local decisions, although this power had reduced with decentralization.

The local prefects implemented State policies, including responsibility for housing. In theory, departmental prefects were entitled to access 25 per cent of all social housing vacancies for disadvantaged people, plus 5 per cent to house civil servants.55 This ‘prefectural contingent’ had fallen into disuse in most areas,56 although the new 2007 right of action against the government might have partly revived this.57

In Figure 1.4, the main democratic local councils are listed in descending order of size: region, département, communauté, and commune. The large cities of Paris, Marseilles and Lyon have yet another lower level, the arrondissement, and were given their own mayors (with limited powers) in 1982.58 None of these councils were hierarchically inferior to each other and all could intervene in housing.59

The support of the mayor was essential for a successful local housing policy. Mayors were the executive officer of the commune, the smallest local government unit (unless subdivided into arrondissements in large cities). At the same time, they were also the local representative of the central State under the prefect. Mayors had multiple roles in...