- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dramatherapy: Theory and Practice 2

About this book

Dramatherapy: Theory and Practice 2 provides both clinician and theatre artist with a basic overview of recent developments in dramatherapy. The international contributors, all practising dramatherapists or psychotherapists, offer a wide variety of perspectives from contrasting theoretical backgrounds, showing how it is possible to integrate a dramatherapeutic approach into many different ways of working towards mental health.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

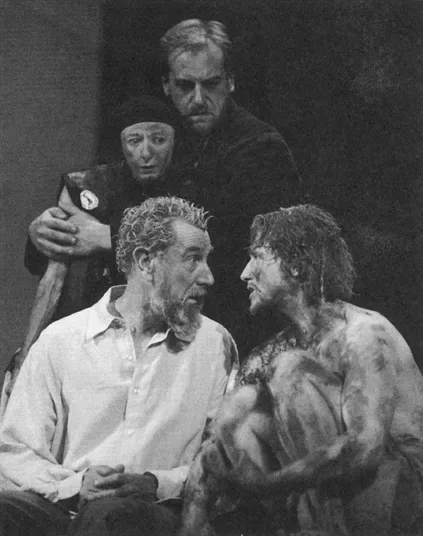

Figure 1.1 John Wood, David Troughton, Linus Roache and Linda Kerr Scott in Nicholas Hytner's production of King Lear, RSC, 1990 (Joe Cocks Studio)

Chapter 1

‘Reason in madness’

Therapeutic journeys through King Lear

Sue Jennings

Dramatherapy is a means of bringing about change in individuals and groups through direct experience of theatre art. Although the techniques of drama are the means whereby this happens, it is the process of the theatre art form that is at the core of this experience. It allows participants and audience to step into dramatic reality from everyday reality, through which creation and re-creation is engendered in new and unexpected ways.

It is not enough for us to read or watch a play or a myth — however much this might engage and absorb us. It is the actual embodiment of the character and scenario which involves us physically in all our senses and thoughts. It allows both an inner expansion of experience and an outer clarification of perception.

As dramatherapists, we may work with people on the direct experiences of their own lives that are painful or unresolved; we may, through the drama, practise behaviours that are unhelpful or inappropriate. We may also take clients fully into the therapeutic theatre art, which establishes a dramatic or theatrical distance from their immediate experience in order to free other aspects of the self. It is indeed a paradox of dramatherapy that theatrical distance enables people to come closer and engage more profoundly with damaged or buried aspects of themselves.

Such a creative journey needs preparation, and most participants need to develop more fully their vocal and physical resources. Spontaneous drama of the moment, may well permit an imaginative leap into therapeutic exploration. However, time spent on the preparation through movement, voice, and drama games, allows a fuller engagement with the drama and brings about a flexibility of possibilities — a myriad of different journeys. Many therapeutic programmes already have drama activities which in themselves are health-promoting and enjoyable. Let us also see them as a means of preparation for a more major step forward into the drama. If human beings only explore within their own experience and with their limited and damaged selves, there is always a boundary on how far we can journey. Ultimately we still have limitations and wounds — even though there is some amelioration. But if we are also able to better equip ourselves for the journey, there are greater possibilities of going beyond the boundary into new and fertile land. It is comparable to people going on a skiing holiday. With no initial preparation, physically or mentally, they may develop severe cramp and have to limp back to base, or they may feel they can only stay on the nursery slopes; they may push on resolutely, and then find that a dangerous fall makes it impossible to try again, or they may feel they can only stay within the safety of social events at the sports centre. The more difficult and complex the journey, the greater is the preparation needed.

What should the preparation entail? Vocal and physical techniques such as those in an actor's training are necessary. For the actor or performer of any kind, the human body is the instrument of experience and communication. The more it is expanded, the more the person can experience. It is not enough just to try these methods; as in any training, repetition in itself brings about greater freedom. Drama games1 are an important way of learning control as well as developing the imagination. Young children play games and invent new ones spontaneously, and through them they learn body control, anticipation, danger and problem-solving. Drama games teach us about ritual — the repetition that provides security and the known base, and also the risk; the delightful danger of grandmother turning round to see if we have moved as we follow in her footsteps. I emphasise the importance of repetition in drama games and ritual, not only to provide the safety of the known, but also because it allows us to refine and perfect the experience.2

For the purpose of this chapter, I am taking the preparation outlined briefly above as a given, as a necessary way into more developed dramatherapeutic work. How then may we progress from the preparation for the journey to aspects of the journey itself?

The task I now set myself is: how can an understanding of a Shakespeare play assist a dramatherapist in practice? I propose to tackle the question by describing journeys through the play of King Lear, both in relation to several Lear productions and workshops, and also Lear images and themes that recur in dramatherapeutic work with groups and individuals. I maintain that an in-depth understanding of the play provides the dramatherapist with a wealth of archetypal material, as well as sharpening their responses to a plethora of imagery: indeed, King Lear is full of dramatic structures that can be directly applied in therapeutic work.

Over the years, King Lear has stimulated a vast amount of literary criticism and interpretation.3 Each decade seems to bring about a new perspective on this great play. It is surely indicative of the play's greatness that it can continually harvest new understanding. Therefore, it is impossible to say that King Lear is about any one phenomenon; rather, it yields multiple crops of fruit, to which one can repeatedly say: ‘and that's true too’ (King Lear, V.ii:12).

As actor Linus Roache said in an interview about his performance of Edgar in Nicholas Hytner's 1990 RSC production of King Lear: ‘there's no finite or definite way of doing it.… The play will just go on and on and on … mining new truths from it.’ (Jennings, 1990b).

The play of King Lear tells how Lear, aged King of England, intends to abdicate by dividing the kingdom between his three daughters. Unlike her sisters, Cordelia, the youngest and Lear's favourite, cannot make a fulsome declaration of love for her father before the assembled court. In unreasoning rage, Lear rejects her, giving the whole kingdom to Goneril and Regan. The Earl of Kent is banished by Lear when he tries to intervene, but Cordelia, although without a dowry, is accepted in marriage by the King of France. Edmund, bastard son of the Earl of Gloucester, tricks his father into disinheriting the legitimate elder son, Edgar, who is forced into hiding disguised as a Bedlam beggar, Poor Tom. Kent has concealed himself as a soldier and remains with Lear's followers. Goneril and Regan, unwilling to support their father's large retinue, quarrel with Lear who rushes out into the night and storm with only his Fool and Kent. They meet the disguised Edgar before Lear is taken to Dover where Cordelia has landed with an army. Gloucester tries to help the king, but is betrayed by Edmund and has his eyes put out by Regan and her husband. In his blindness, Gloucester is led to Dover by Poor Tom, not recognising his own son. After the battle in which Lear and Cordelia are defeated, Edmund and Edgar fight a duel. Edmund is killed, but Cordelia, on his orders, has been hanged in prison. Lear dies trying to revive Cordelia.

SIGNIFICANT THEMES

Families

The play concerns the dynamics of two families, Lear and his three daughters, and Gloucester and his two sons. The families are linked by the fact that Lear is godfather to Gloucester's legitimate son, Edgar. Traditional readings of the play have usually portrayed Lear as a sad, misunderstood father, with an older and middle daughter who personify evil, and a younger daughter who is all that is good.

One interpretation of the play is that it is based on a Cinderella-like fairytale. If one takes the view that Lear is a fairytale or myth, then Lear's demand that his daughters should publicly state how much they love him — the public ‘test’ — is a mythic convention, recurring in many forms. However, recent productions have not set the play in such a convention, and thus Lear's demand may be seen as an unreasonable and manipulative request, taking place in the public domain of the political court. This latter interpretation appears equally valid, especially since there is no suggestion in the play that there is to be a ‘test’ of the daughter's love: indeed, Lear's stated intention (I.i:35–43) explicitly describes his political decision to divide the kingdom in order to prevent political strife, and to allow younger people to take responsibility for his realm.

The tone changes when Lear says: ‘Which of you shall we say doth love us most?’ (I.i:50).

Both the older and middle sister, Goneril and Regan, make an attempt to state their love, and Cordelia, the youngest daughter, stays silent. The reply of the older two daughters appears to satisfy their father, and Cordelia's silence produces a torrent of words, anger and recrimination from him, which ends up in her being disinherited and disavowed. Even when others intervene, Lear pushes his resolve to the extreme and invokes the gods (the mysteries of Hecate and the Night, Apollo and Jupiter) to uphold his decision. So, having reacted with rage and abuse to Cordelia's silence or her unwillingness ‘to play the game’, he compounds his resolve by swearing to the gods, making his action inviolate.

In several workshops, we explored father/daughter relationships, taking single lines from Lear and then developing improvisation. We took the following lines: ‘Meantime, we shall express our darker purpose’ (I.i:35); and ‘Sir, I love you more than word can wield the matter’ (I.i:54).

The improvisations ranged through a series of scenarios involving middle-aged daughters with aging fathers. Each time, the people who played the daughters ended up exasperated at the manipulation of the aging father: for example, one father attempted to persuade his daughter to allow him to move into an already overcrowded family home. He used as his persuasion the fact that he had already paid his daughter some of his savings in order to avoid tax. The daughter found herself, in the end, saying extreme things to her father in order to try and get him to understand, such as, ‘Well, if you really can't look after yourself, we shall have to put you in a Home’, and, ‘Well that's it then, if we can't have a sensible conversation, I shan't come around anymore’. In reflection on the improvisations afterwards, many of the people who themselves worked with elderly people, commented that they had never realised how an irascible old man could push them to their limits. Rather than seeing Lear only as a poor old man to be pitied, they now felt that his behaviour was quite unreasonable. As the improvisations developed further, the above reactions carried over from the test of love, into the scenes where Lear goes to live with his eldest daughter and then attempts to move into his middle daughter's home. Again, Goneril felt that her father's behaviour in continuing to keep a retinue of many soldiers and giving orders to her household was unacceptable. In both the recent (1990/1) productions by the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal National Theatre, the soldiers are boisterous, noisy and very male. Goneril's exasperation seems a reasonable response to a feeling of being pushed beyond her limits.

The point of these explorations was not to suggest that either side was right or wrong, but to gain insight into the complex relationship between elderly parents and their children. It is particularly relevant to the contemporary context in which the nuclear family is seen as parents and dependent children rather than as three generations. The above described dynamic would probably not have come about several decades ago, where there was an expectation that children would care for their aging parents and that the aged parent would continue to play a dominant role in the running of the household.

The sub-text of another set of improvisations based on fathers and daughters, taking the lines ‘What shall Cordelia speak? Love, and be silent’ (I.i:61,62), and ‘Sure I shall never marry like my sisters, To love my father all’ (I.i:101,102), moved on from the overt themes of Cordelia's unwillingness to state her filial affection and Lear's verbiage in the public domain, to an examination of the nature of the relationship between Lear and his daughter. Many interpretations of the play make Cordelia very young, almost an Ophelia-figure, who, similarly, is a victim of her circumstances.

G. Wilson Knight (1949) suggests that the tragedy of this play is not Lear's, but Cordelia's, and that it is the tragedy ‘par excellence of the innocent victim’. However, why is Cordelia still single and still living with her widowed father? She is obviously not a teenager, since Lear says he is 80, and one is forced to speculate on the seeming gross dependency between Cordelia and Lear. In one workshop, some of the improvisations went as far as to develop themes of incest and child sexual abuse; again, not a surprising theme in relation to our contemporary awareness and open discussion of child abuse, especially within families.

How far is Cordelia struggling to deal with the position of being the favourite child, still at home and looking after her aged father, and as yet not forming an adult peer/spouse relationship. As she attempts to speak, she is unable ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and tables

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Reason in madness’: therapeutic journeys through King Lear

- 2 The place of metaphor in psychotherapy supervision: creative tensions between forensic psychotherapy and dramatherapy

- 3 Therapy in drama

- 4 Therapeutic theatre: a para-theatrical model of dramatherapy

- 5 Enactment, therapy and behaviour

- 6 The building blocks of dramatherapy

- 7 One-on-one: the role of the dramatherapist working with individuals

- 8 The dramatherapist ‘in-role’

- 9 Playtherapy and dramatic play with young children who have been abused

- 10 Story-making in assessment method for coping with stress: six-piece story-making and BASIC Ph

- 11 Dramatherapy and thought-disorder

- 12 Theatre as community therapy: an exploration of the interrelationship between the audience and the theatre

- Name index

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dramatherapy: Theory and Practice 2 by Sue Jennings in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.