This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Atlas of Jewish History

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this illuminating history, Dan Cohn-Sherbok traces the development of Jewish history from ancient times to the present day. Containing over 100 maps and 30 photographs, this is a comprehensive atlas of Jewish history designed for students and the general reader. It is ideally suited for those courses in Jewish or Biblical Studies, serving as a handy reference guide as well as a textbook.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Atlas of Jewish History by Dan Cohn-Sherbok in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Weltgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST AND THE ISRAELITES

Ancient Mesopotamian and Canaanite civilization

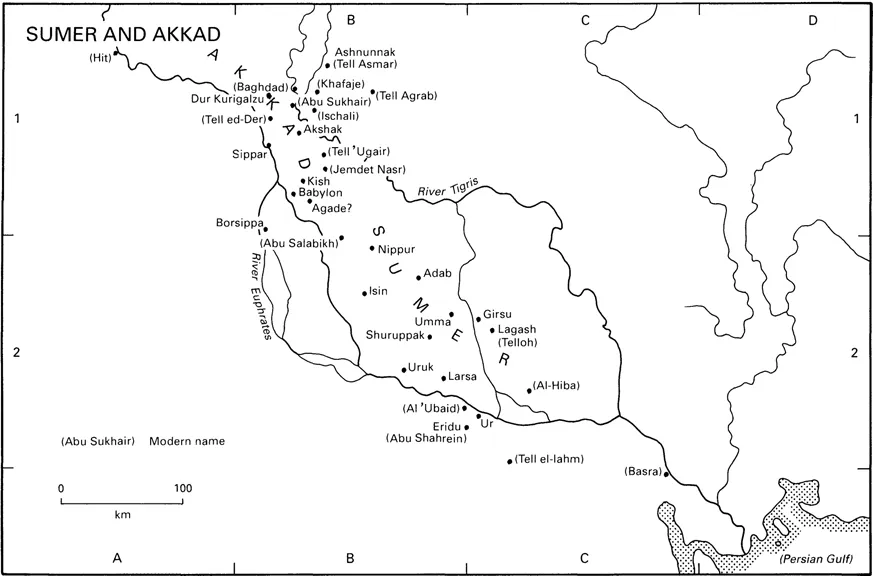

The rise of ancient Mesopotamian civilization occurred at the end of the fourth millennium in southern Mesopotamia alongside the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, where the Sumerians created city states, each with its local god. In Uruk there were two main temples: one was for Anu, the god of heaven; the other was for Inanna, the mother goddess of fertility, love and war. In addition, other deities were worshipped at other places – Enlil, lord of the atmosphere at Nippur; Utu, the sun god, at Larsa; Nanna, the moon god, at Ur. Each of these gods had a family and servants who were also worshipped at various shrines. The temple itself was located on a high platform and housed in a holy room in which a statue of the god was washed, dressed and fed each day. Through the centuries, Sumerian priests recounted stories about these gods, whose actions were restricted to various spheres of influence. In addition, the Sumerian myths contain legends about creation: Enlil, for example, separated heaven from earth, and Enki created man to grow food for himself and the gods.

During the next millennium, waves of Semitic people (known as the Akkadians) settled amongst the Sumerians, adopting their writing and culture. From 2300 BC, when Sargon of Akkad established the first Semitic empire, they dominated Mesopotamia. At this time Sumerian stories were recorded in the Semitic language, Akkadian. These Semites reshaped Sumerian culture, equating some of their gods with the Sumerian ones. Anu, for example, was identified with El; Inanna with Ishtar; Enki with Ea. In Akkadian schools epics of the gods were chronicled. The Gilgamesh epic, for example, depicts King Gilgamesh, who ruled Uruk in about 2700 BC.

For the Sumerians and the Akkadians, life was controlled by the gods. To obtain happiness, it was mandatory to keep the gods in a good humour through worship and sacrifice. None the less the gods were unpredictable, and this gave rise to the reading of omens. In the birth of monstrosities, the movements of animals, the shapes of cracks in the wall and the oil poured into water these peoples perceived the fingers of the gods pointing to the future. Thus if a person wished to marry, or a king chose to wage war, they would consult omens. Another frequent practice was to examine the liver of a sacrificed animal – a special class of priests was trained to interpret such signs.

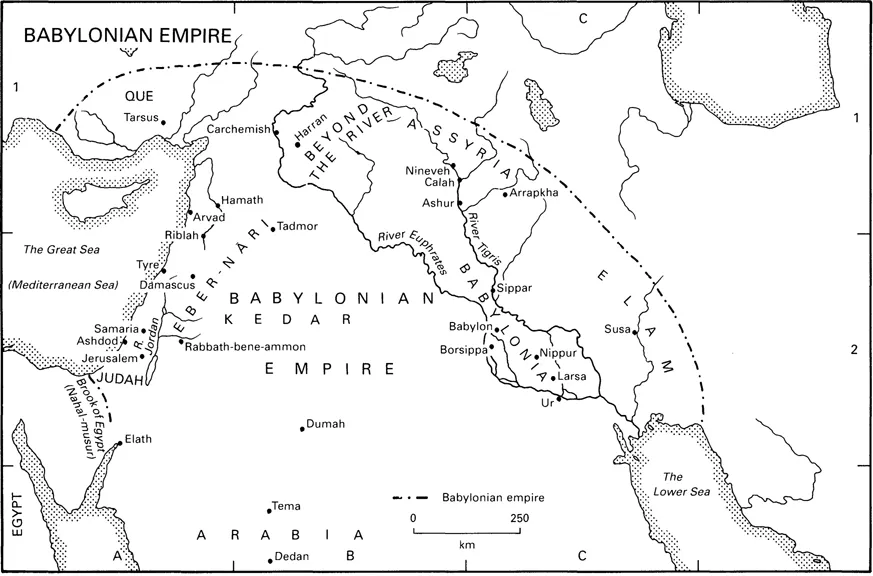

At its height Sargon’s and his descendants’ empire stretched from the Persian coast to the Syrian shores of the Mediterranean. However, this kingdom collapsed in about 2200 BC through invasion and internal conflict. Among the new arrivals in Mesopotamia were the Amorites, who dwelt in Mesopotamian cities such as Mari and Babylon, where they assimilated Sumero-Akkadian culture. Other Amorites penetrated into ancient Canaan, where they retained their separate tribal structure. The collapse of the Akkadian empire was followed by a Sumerian revival in the Third Dynasty of Ur (2060–1950 BC). During this period Hammurabi of Babylon reigned from 1792 to 1750 BC; as a tribute the Babylonian creation story (‘Enuma Elish’) was composed in his honour. In c. 1400 BC the state of Assyria grew strong in northern Mesopotamia and later became the dominant power in the Near East. The Assyrian kings imitated the Babylonians; they worshipped the same gods, but their chief god (identified with Enlil) was Ashur.

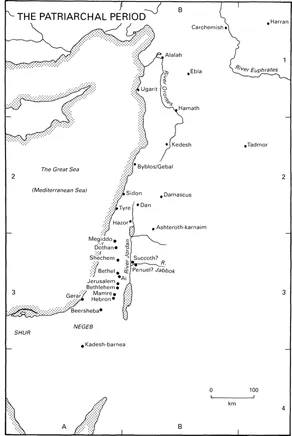

In the second millennium, the inhabitants of Canaan were composed of a mixture of races largely of Semitic origin. Excavations have unearthed the remains of small temples in Canaanite towns; these housed cultic statutes in niches opposite doorways. When temples had courtyards, worshippers remained outside while priests entered the sanctuary. A large altar was placed in the courtyard and a smaller one inside the temple. The animal remains from these places of worship suggest that offerings consisted mainly of lambs and kids. Liquid offerings of wine and oil were also contributed, and incense was burned. In some temples, stone pillars were erected as memorials to the dead; other pillars served as symbols of gods. Statues of gods and goddesses were carved in stone or moulded in metal overlaid with gold, dressed in expensive clothes, and decorated with jewellery. To the north of Canaan, excavations of the city of Ugarit have provided additional information about religious practices. The texts of Ugarit emphasize that the gods of Canaan were like many others of the ancient Near East: they were powers of the natural world. El was the father of gods and men; his wife was Asherah, the mother goddess. El had a daughter Anat who personified war and love and is portrayed in some accounts as the lover of her brother, Baal (the god of weather). The texts of Ugarit depict Baal’s victory over Yam (the sea) and against Mot (the god of death). Additional gods include Shapash, the sun goddess; Yarikh, the moon god; Eshmun, the healer. This Canaanite religious structure as well as the earlier Sumerian and Akkadian civilizations provide the backdrop for the emergence of the religion of the Jewish people.

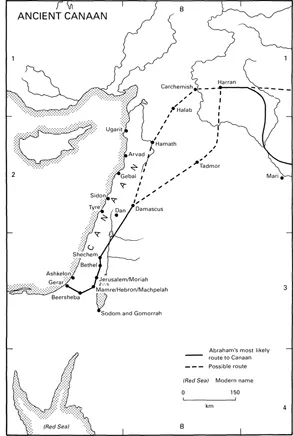

The patriarchs and Joseph

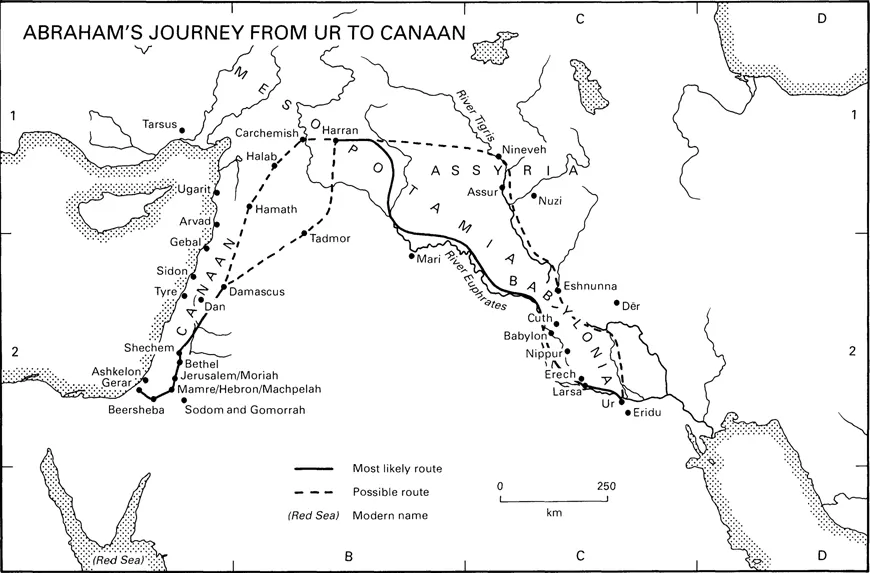

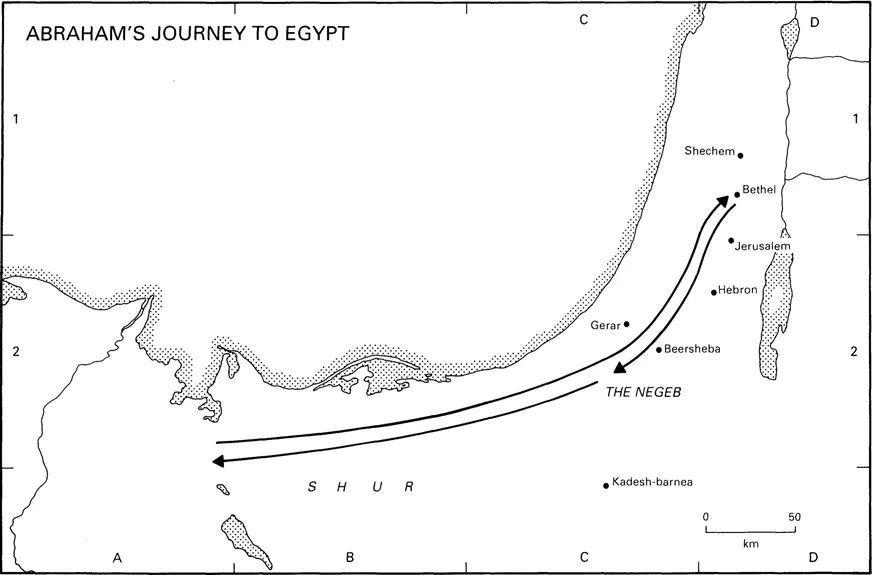

The biblical account in Genesis depicts Abraham as the father of the Jewish nation. Initially known as Abram, he came from Ur of the Chaldeans – a Sumerian city of Mesopotamia. Together with his father Terah, his wife Sarai and his nephew Lot, he went to Harran, a trading centre in northern Syria. There his father died, and God told him to go to Canaan: ‘Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation’ (Genesis 12:1–2). During a famine in Canaan he went first to Egypt and then to the Negeb. Finally he settled in the plain near Hebron, where he experienced a revelation confirming that his deliverance from Ur was an act of providence: ‘I am the Lord who brought you from Ur of the Chaldeans to give you this land to possess’ (Genesis 15:7).

Because Sarai was barren Abram had relations with her servant girl, Hagar, who bore Ishmael. However, when Abram was ninety-nine and Sarai ninety, God gave them a son, Isaac. It was at this time that Abram received his new name Abraham (‘the father of a multitude’), and Sarai was renamed Sarah (‘princess’). When Isaac was born, Abraham sent Hagar and Ishmael away at Sarah’s insistence. During this period God made a covenant with Abraham symbolized by an act of circumcision: ‘You shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskins, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and you’ (Genesis 17:11). Subsequently God tested Abraham’s dedication by ordering him to sacrifice his son Isaac, only telling him at the last moment to desist. When Isaac grew older, Abraham sent a servant to his kinsfolk in Hebron to find him a wife. The messenger returned with Rebecca. Later God answered Isaac’s prayers for a son, and twins (Esau and Jacob) were born. Jacob bought his brother’s birthright for food, and with his mother’s help secured Isaac’s blessing, thereby inflaming Esau’s wrath. Fleeing from his brother, Jacob travelled northward toward Harran; en route he had a vision of a ladder rising to heaven. There he heard God speak to him, promising him that his offspring would inherit the land and fill the earth (Genesis 28:12–14). After arriving in Harran Jacob laboured for his uncle Laban for twenty years as a shepherd. There he married Laban’s daughters, Rachel and Leah; they and their maids (Bilhah and Zilpah) bore him twelve sons and a daughter. Eventually Jacob returned to Canaan. On this journey he wrestled with a mysterious stranger in the gorge of the Jabbok river, a tributary of the Jordan, where God bestowed upon him the new name, ‘Israel’.

When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he touched the hollow of his thigh; and Jacob’s thigh was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, ‘Let me go, for the day is breaking.’ But Jacob said, ‘I will not let you go, unless you bless me.’ And he said to him, ‘What is your name?’ And he said, ‘Jacob’. Then he said, ‘Your name shall no more be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men and have prevailed.

(Genesis 32: 25–8)

Eventually Jacob was welcomed by Esau, but then the brothers parted. Jacob lived in Canaan until one of his own sons, Joseph, requested that he and his family settle in Egypt, where he died at the age of 147.

The history of the three patriarchs is followed by the narrative of Jacob’s son, Joseph. As a young boy, Joseph was given a special long-sleeved robe as a sign that he was his father’s favourite. With his brothers he tended his family flocks in Shechem, but he infuriated them by recounting dreams in which they bowed down to him. Furious at this presumption, they plotted his death. However, Reuben, one of the brothers, persuaded them to wait, and another, Judah, suggested that Joseph should be sold as a slave rather than be killed. Eventually Joseph was taken as a slave to Egypt; his brothers dipped his coat in a kid’s blood, declaring to Jacob that he had been mauled by a wild animal. In Egypt Joseph first served in the house of Potiphar, but was falsely accused by Potiphar’s wife of rape. As a result he was cast into prison. In time he was released by the reigning pharaoh in order to interpret his dreams; subsequently he became chief minister of the land. After the outbreak of famine, he enabled the country to become rich. When his brothers came before him to buy grain, he revealed to them his identity, assuring them that all was guided by God’s providential care:

I am your brother Joseph whom you sold in Egypt. And now do not be distressed because you sold me here; for God sent me before you to preserve life.

(Genesis 45: 4–5)

At the age of 110 Joseph died, and his family remained in Egypt, where they prospered. Yet with the arrival of a pharaoh ‘who did not know Joseph’ (Exodus 1:8), the Jewish people were forced to labour as slaves on the construction of the royal cities of Pithom and Raamses. According to Scripture, this pharaoh declared that all male offspring should be killed at birth: ‘Every son that is born to the Hebrews–you shall cast into the Nile, but you shall let every daughter live’ (Exodus 1:22).

Figure 1 Jacob wrestling with the angel, Rembrandt

(Gemaldegalerie, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

Ancient Egypt

Paralleling the rise of Mesopotamian civilization, Egyptian culture reached great heights in the third millennium. In c. 3000 BC an Upper Egyptian king, Narmer, conquered Lower Egypt, unifying both portions of the land. With the collapse of the Old Kingdom in c. 2200 BC Egypt suffered political anarchy and civil war which lasted over two centuries. However, with the accession of Amenehmet I of the Twelfth Dynasty (c. 1990 BC), the Middle Kingdom enjoyed considerable prosperity – this period coincided with the patriarchal period in Palestine, and it appears that interrelations existed between the two regions.

In c. 1780 BC the Middle Kingdom collapsed. As a result, chaos ensued. About fifty years later the Delta was ruled over by the Hyksos of Asian descent; their rule lasted until c. 1570 BC. Around 1550 BC the Egyptian rulers of Thebes began a war of liberation against the Hyksos – this resulted in the capture of the Hyksos capital at Avaris, and the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt. To prevent the reccurrence of such foreign domination, the rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty extended their domination east and north into west Asia. Under Thutmose (c. 1490–1436 BC), the foundations of Egypt’s Asiatic empire were laid. His two successors continued his policies until the reign of Amunhotep III (c. 1405–1367 BC). During this period the national god, Amun of Thebes, was regarded as having given victory to Egypt.

Under Amunhotep’s son Akhenaton (c. 1367–1350 BC), a social revolution occurred. Akhenaton attempted to revolutionize religious life by suppressing the cult of Amun and other major gods and replacing them with worship of the sundisk Aton. Such reforms resembled monotheism, yet Akhenaton’s revolution did not survive his death. At the death of Akhenaton’s successor Tutankhamun, Egypt was defeated in Asia in a war against the Hittites and a civil war in Egypt led to the independence of Canaan. From c. 1304–1200 BC the Ramesside kings of the Nineteenth Dynasty re-established Egyptian control and Egyptian garrisons were placed in various Canaanite cities. Rameses II (c. 1290–1273 BC), the most famous king of the dynasty, fought a battle with the resurgent Hittites at Kedesh on the Orontes. This battle established the northern limits of Egyptian control and influence in southern Syria.

According to tradition the Exodus of the Israelites from Egyptian captivity occurred rtowards the last quarter of the second millennium BC during the reign of Raameses II. Thus the Book of Exodus relates: ‘Therefore they did set over them taskmasters to afflict them with their burdens. And they built for Pharaoh store-cities, Pithom and Raamses.’ As the greatest builder of the Nineteenth Dynasty New Kingdom Raameses engaged in building works at these two sites, employing vast numbers of slaves. Yet most scholars believe that the Israelites escaped during the reign of his successor Merneptah. A victory stele of this pharaoh dated 1220 BC relates that he won a battle in Canaan and mentions the defeated people as ‘Israel’. Taken in conjunction with biblical evide...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of maps

- Acknowledgements

- 1. The Ancient Near East and the Israelites

- 2. The Rise of Monarchy and the Two Kingdoms

- 3. Captivity and Return

- 4. From Herod to Rebellion

- 5. Jewry in Palestine and Babylonia

- 6. Judaism Under Islam in the Middle Ages

- 7. Jews in Medieval Christian Europe

- 8. Medieval Jewish Thought

- 9. Western European Jewry in the Early Modern Period

- 10. Eastern Europe an JeWry in the Early Modern Period

- 11. Jews in Europe in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

- 12. The Development of Reform Judaism

- 13. Jewry in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

- 14. The Holocaust

- 15. Israel

- List of further reading

- Gazetteer