Chapter 1

Feminists and the global sex industry

Cheerleaders or critics?

National sex industries and the global sex industry are currently experiencing startling growth and profit levels (IBISWorld, 2007; Poulin, 2005). In consonance, the many problems that are now being recognized as intrinsically linked to the industry, harms to the health of women and girls (Jeffreys, 2004), organized crime and corruption (M. Sullivan, 2007), trafficking (Farr, 2004; Monzini, 2005), the early sexualization of girls (American Psychological Association, 2007), are growing apace. It is surprising in this context that many theorists and researchers on prostitution who define themselves as feminists, or concern themselves primarily with the interests of women, are increasingly using euphemisms in their approach to prostitution. The language of feminist theorists on prostitution was affected by the normalization of the industry in the last decades of the 20th century. Though some remained critical (Barry, 1995; Jeffreys, 1997; Stark and Whisnant, 2004), many started to use a language more in tune with the neo-liberal economists, such as Milton Friedman, who were calling for the decriminalization of prostitution and its treatment just like any other industry. They began to use terms such as ‘agency’, ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘rational choice’ to describe the experience of prostituted women. These approaches are a public relations victory for the international sex industry. In this chapter I shall critically analyse the neo-liberal language and ideas that many feminists have adopted to see whether they are suited to the new realities.

The main vectors of neo-liberal language in relation to prostitution are the sex work agencies set up or funded by governments to supply condoms to prostituted women and men against the transmission of HIV. This ‘AIDS money’ has created a powerful force of sex workers’ rights organizations which take the position that prostitution is just a job like any other, and now a useful market sector that must be decriminalized. Leading propagandists of this movement argue that AIDS funding has been crucial to their success in pushing the decriminalization argument (Doezema, 1998b). The international umbrella grouping of these sex work organizations is the Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) which uses neo-liberal understandings of prostitution to coordinate the international campaign for decriminalization through the work of activists such as Laura Agustin (2004, 2006b), and Jo Doezema (1998b). Jo Doezema, an NSWP spokeswoman, argues that AIDS money gave a big impetus to the campaign. She says: ‘The original impetus for the NSWP came from the huge amount of interest in sex workers due to the AIDS pandemic. Vast amounts of resources were pumped into projects and research to stop sex workers from spreading AIDS’ (Murphy and Ringheim, n.d.). Kamala Kempadoo, a significant researcher in the area of sex tourism and prostitution in the Caribbean who takes a sex work position, echoes the importance of AIDS money: ‘some AIDS-prevention work has contributed to the formation of new sex worker organizations, inadvertently empowering sex workers in other areas than just in health matters’ (Kempadoo, 1998, p. 19).

With the advent of AIDS funding, sex worker activists gained platforms and an authority, as experts in a supposed public health crisis, that enabled the creation of a strong, international pro sex work lobby group. Sex worker activists sometimes direct fury at those who point out the harms of prostitution, and this anger can influence feminists who have previously been critical of prostitution into changing their positions (B. Sullivan, 1994). In an example of this fury, Cheryl Overs refers to the work of academic feminists who challenge trafficking in women and are critical of prostitution as ‘the drivel about sexual slavery that is produced in American “women’s studies” departments and exported in a blatant act of cultural imperialism’ (Doezema, 1998a, p. 206). The influence of the sex work position has been most marked in international health politics, UNAIDS and the ILO (Oriel, forthcoming). The position is a comfortable one for governments and UN agencies to adopt because it offers no challenge to the rights of men to buy women for sex. It represents a return to the 19th century situation before feminists initiated the campaign against the contagious diseases acts in the UK in the 1860s (Jeffreys, 1985a). At that time men’s prostitution behaviour, that is buying women for sex, was an unchallenged prerogative. There were prostitution survivors who set up organizations in the 1980s and 1990s in the US from a very different viewpoint, such as WHISPER (Women Hurt in Systems of Prostitution Engaged in Revolt) (Giobbe, 1990) and SAGE (Standing Against Global Exploitation) (Hotaling, 1999) and Breaking Free (V. Carter, 1999). All these groups argue that prostitution should be understood as violence against women, but their views have not been so influential, perhaps because they do not fit the politics and practice of neo-liberal economics so well.

The sex work position appealed to socialist feminists in particular because they were prepared to see prostitution as an issue of workers’ rights rather than one of violence against women. Socialist feminist theory and action have focused less on violence against women and more on issues of work and the economy. The sex work position had considerable influence on feminist debate, also, because many feminist academics and activists from different points of view were keen to listen to and respect the views of those women who represented themselves as having experience of prostitution, and spokespersons of sex work organizations were generally uncritical (Jeffreys, 1995). When some sex work groups said that prostitution was a positive experience, an exercise of personal choice and should be seen as legitimate work, some found it hard to disagree. The fact that there were survivors expressing very different perspectives, and that adoption of a sex work perspective involved a conscious choice to reject these other views, did not cause as much concern as it should have. Radical feminists, on the other hand, were not prepared to see prostitution as ordinary work because their backgrounds lay in researching and working on violence against women, particularly sexual violence. They recognized the similarities between the experience of prostituted women and rape victims, such as having to disassociate emotionally from their bodies to survive, and suffering symptoms of post-traumatic shock and negative feelings about their bodies and their selves (Jeffreys, 1997; Farley, 2003).

The radical feminist philosopher Kathy Miriam explains the apparently positive motivation behind the adoption of the pro sex work position. She says that this position ‘casts sex workers’ rights in terms of a politics of “recognition”’ which ‘pivots on “identity” as its moral/political fulcrum and aims at redressing injuries to status, for example stigma and degradation, as a basic harm or injustice inflicted on certain identity-groups’ (Miriam, 2005, p. 7). When this approach is applied to prostitution, ‘the stigmatization of prostitutes – rather than the structure of the practice itself – becomes the basic injustice to be redressed by pro-sex-work advocates’ (ibid.). Miriam explains that though this approach may well be founded upon the positive motivation of dealing justice to a stigmatized group, it makes it very difficult to see the ‘relations of dominance and subordination’ that underlie prostitution, particularly in forms that go beyond obvious force. Though the impulse towards adopting a sex work position might have been progressive on the part of many of the theorists and activists who adopted it, the language and concepts of the position are precisely those that most suit the present economic ideology of neo-liberalism. They can, as Miriam points out, veer towards a decontextualized individualism of personal choice which is quite far from the politics of gender, race and class that is at the root of both socialist and radical feminism. They can even go so far as to support a free market, deregulationist approach to prostitution which suits the interests of sex industrialists rather than the girls and women caught up in the industry. Since radical feminists have focused more on the politics of the personal, such as how power relations are represented in women’s everyday relationships with men, they have tended to be less well represented in theorizing international politics than socialist feminists. Those radical feminists who have been writing in the area of international politics have tended to concentrate on issues of violence against women, including prostitution (Kelly, 2000; Jeffreys, 1997; Barry, 1995). The sex work position has, therefore, tended to predominate in international feminist political theory through socialist feminist work which privileges a workers’ rights or politics of identity approach.

Prostitution as reproductive labour

One upshot of the adoption of the sex work position is that many feminist theorists of the international political economy have lumped prostitution in with domestic labour in the category of ‘reproductive labour’ (Peterson, 2003; Jyoti Sanghera, 1997). When serious feminist critics of globalization mention prostitution it is usually not problematized, since reproductive labour is an area of women’s work that such theorists tend to valorize in compensation for the way in which women’s work, particularly unpaid work in the home, has been ignored in economic theory. Theorists such as Spike Peterson (2003), Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Hochschild (2003), have pointed out that the ‘service sector’, which is becoming more and more significant in rich countries as manufacturing is outsourced to the poor world, represents to a large extent work that women have always carried out in the private sphere with no pay. Once commercialized as ‘services’, this work attracts payment in the form of domestic labour, or caring work. These writers, less convincingly, tack on prostitution to this analysis and point to ‘sex work’ being paid for as ‘sexual services’. Identifying prostitution as a form of reproductive labour is a category error. Domestic labour fits this category in a way that prostitution does not, particularly because ‘reproductive labour’ is defined as ‘socially necessary’ (Peterson, 2003, p. 94; Jyoti Sanghera, 1997). Though arguably the preparation of food and care of children is ‘socially necessary’, and indeed men may, though they do not much at present, do it too, prostitution is not. The idea of ‘social necessity’ in relation to prostitution applies specifically to men. Prostitution is a socially constructed idea (Jeffreys, 1997) and behaviour which may be necessary to the maintenance of male dominance, but is not in any way socially necessary to women.

There is another problem with recognizing ‘sexual services’ as part of reproductive labour. This could imply that providing sexual access to men whilst they disassociate is an ordinary part of women’s work in the home, which would undermine decades of feminist work to end the requirement that women engage in unwanted sex which has no connection with their pleasure. Prostitution may outsource that part of women’s obligations under male domination that they most despise and are particularly harmed by. It is not the same as cleaning or baking cakes. One good indication of this is the fact that youth and inexperience are the most highly valued aspects of a girl inducted into prostitution. She will never be as valuable to her handlers as she is at the moment at which she is first raped, which may be as early as 10 years old (Saeed, 2001). Maids are not most valuable when they are children and do not know what they are doing. It is more useful to see prostitution as the outsourcing of women’s subordination, rather than the outsourcing of an ordinary form of servicing work which just happens to be performed by women.

Choice and agency

The sex work position employs an individualist approach, representing the diverse aspects of prostitution, such as stripping, as areas in which women can exercise choice and agency or even be empowered (Hanna, 1998; Schweitzer, 1999; Liepe-Levinson, 2002; Egan, 2006). This approach is in rather sharp contradiction to the industrialization of prostitution which has been taking place in recent decades. As Carole Pateman points out, when socialist feminists adopt this approach to prostitution they end up being rather more positive and context blind in relation to prostitution than they would be towards other kinds of work, which are understood to be carried out in relations of domination and subordination (Pateman, 1988). Until recently the sex work position was mainly confined to research on forms of prostitution in the west, where prostituted women could be seen by ‘choice’ theorists as having the possibility of engaging in a variety of occupations to maintain subsistence. Now, however, the use of liberal individualist language, and even rational choice theory, has been extended to describe the most impressively unlikely situations in the non-west.

Alys Willman-Navarro, for instance, uses the language of rational choice in an issue of the journal Research for Sex Work, on ‘Sex Work and Money’ (2006). The journal publishes material from sex work organizations from different countries. She looks at research literature showing that prostituted women in Calcutta and Mexico engage in sex with prostitutors without condoms because they know ‘sex workers who are willing to perform unprotected sex will be compensated for doing so, while those who prefer to use condoms earn less’, a loss which can be as much as 79 per cent of earnings (Willman-Navarro, 2006, p. 18). Such research, she says, shows ‘sex workers’ as ‘rational agents responding to incentives’ (ibid., p. 19). The ‘choice’ between the chance of death from HIV/AIDS and the ability to feed and school her children does not offer sufficient realistic alternatives to qualify as an exercise in ‘agency’. Nonetheless, Willman-Navarro remains upbeat in her approach: ‘In Nicaragua I have met sex workers who are barely making ends meet. I have met others who send their children to some of the best schools in the capital … They didn’t do this by cashing in on one lucky night, but through years of rational choices.’ Women in prostitution, this account tells us, can be successful entrepreneurs if only they act rationally.

Another example of this individualist approach can be found in the work of Travis Kong (2006) on prostituted women in Hong Kong. Kong’s determination to respect the women as self-actualizing and possessed of agency leads to an individualist approach quite at odds with what the research itself reveals about the conditions of the women’s existence. Kong takes the fashionable approach to prostitution of defining it as emotional labour. The concept of emotional labour, developed by Arlie Hochschild (1983), is very useful for analysing much of the paid and unpaid work that women do, such as that of cabin staff on aeroplanes. When this concept is carried over to prostitution, in which what is done to the inside and outside of women’s bodies is the very heart of the ‘work’, it suggests a squeamishness about recognizing the physical details involved, and requires a mind/body split. A large part of the ‘emotional’ work of prostitution is the construction of measures to enable a disassociation of mind from body in order to survive the abuse (Farley, 2003). This is not a usual component of ‘emotional labour’. Kong says that she will employ a ‘poststructuralist conception of power and identity formation’ and ‘depict my respondents as performing the skilled emotional labour of sex in exchange for their clients’ money … I argue that their major problem is not with the commercial transaction … but with the social stigma, surveillance and dangers at their workplaces’ (Kong, 2006, p. 416). These women, Kong explains, are ‘independent workers’ and she expresses some disappointment at how ‘apolitical and conventional’ they are, in contrast with the ‘image of a transgressive sexual and political minority that has been portrayed in the agency model of proprostitution feminism’ (Kong, 2006, p. 415). But when the bald facts of their conditions of work are mentioned they seem to be about the use of their bodies rather than their minds: ‘Since they have ejaculated on us … They won’t rape other women … and they wouldn’t lose their temper when they go home … they won’t ejaculate on their wives when they get home’ (Kong, 2006, p. 420). The example given of how they have to develop ‘skilled work techniques’ is ‘they have to learn to do fellatio’ (Kong, 2006, p. 423). It is interesting to note that a 2007 report on the Australian sex industry states, for the benefit of those seeking to set up brothels, that the work requires no skills training (IBISWorld, 2007).

The postcolonial approach

Exponents of the sex work position can be very critical of those feminists who seek to abolish prostitution and the traffic in women. One major form of criticism is that feminists who seek to abolish prostitution ‘victimize’ prostituted women by not recognizing their ‘agency’. This has been employed against anti-trafficking campaigners and feminists who seek to end prostitution, who are said to ‘victimize’ prostituted women (Kapur, 2002). This criticism is not newly minted in relation to prostitution, but has been common to liberal feminist criticisms of the anti-rape and anti-pornography movements such as the work of Katie Roiphe in the US (Roiphe, 1993; Denfeld, 1995). US liberal feminists of the early 1990s argued that it is important to recognize women’s sexual agency. They said that harping on about sexual violence and the harms that women suffer at the hands of men showed a lack of respect for women’s sexual choices and sexual freedom. It is interesting to note that this idea has been taken up by postcolonial feminists to criticize radical feminists, as in the work of Ratna Kapur (2002).

Kapur says that those who ‘articulate’ the ‘victim subject’, such as suggesting that prostituted women are oppressed or harmed, base their arguments on ‘gender essentialism’ and generalizations which reflect the problems of privileged white, western, middle-class, heterosexual women (Kapur, 2002, p. 6). This accusation implies that those who identify women as being oppressed are ‘classist’ through the very fact of making that identification. Such arguments are based on ‘cultural essentialism’ too, portraying women as victims of their culture, Kapur says. Those guilty of these racist and classist practices are those involved in working against violence. She identifies Catharine MacKinnon and Kathleen Barry in particular, and anti-trafficking campaigners who ‘focus on violence and victimization’. Campaigns against violence against women, she says, ‘have taken feminists back into a protectionist and conservative discourse’ (ibid., p. 7). Anti-violence feminists are accused of using ‘metanarratives’ and erasing the differences between women, and of a lack of complexity that ‘sets up a subject who is thoroughly disempowered and helpless’ (ibid., p. 10). However, it is not just ‘western’ feminists that Kapur criticizes for these solecisms, but Indian ones too who happen to be anti-violence campaigners. They too negate the ‘very possibility of choice or agency’ by saying that ‘sex work’ in South Asia is a form of exploitation (ibid., p. 26). She is critical of what she perceives as an alliance between ‘Western feminists and Indian feminists’ in the human rights arena as a result of which ‘[t]he victim subject has become a de-contextualised, ahistorical subject, disguised superficially as the dowry victim, as the victim of honour killings, or as the victim of trafficking and prostitution’ (ibid., p. 29).

Another argument that Kapur makes is that prostitution is transgressive. This idea fits into the pro sexual freedom position of the new left which led to the promotion of pornography by those creating the 1960s and 1970s ‘counterculture’ (see Jeffreys, 1990/91). She argues that the correct approach for feminist theorists is, therefore, to ‘focus on moments of resistance’ and thus disrupt the ‘linear narrative produced by the VAW [violence against women] campaigns’ and this will ‘complicate the binary of the West and the Rest’ (ibid., p. 29). She explains that she chooses to do this by foregrounding the ‘sex worker’ because ‘[h]er claims as a parent, entertainer, worker and sexual subject disrupt dominant sexual and familial norms. In post-colonial India, her repeated performances also challenge and alter dominant cultural norms. From her peripheral location, the sex worker brings about a normative challenge by negotiating her disclaimed or marginalized identity within more stable and dominant discourses’ (ibid., p. 31). But the idea that prostituted women transgress the social norms of heterosexuality and the heteropatriarchal family is by no means clear in India and Pakistan, where forms of family prostitution thrive (Saeed, 2001; Agrawal, 2006b).

In her research on family prostitution in Bombay in the 1920s and 1930s, Ashwini Tambe specifically refutes the notion that prostituted women should be seen as transgressive (Tambe, 2006). She stresses the continuities between families and brothels. She says that feminist theory is wrong in always locating prostitution ‘outside the ambit of official familial institutions’ (Tambe, 2006, p. 220). She criticizes the idea put forward by what she calls ‘sex radicals’ that prostitution has the potential to ‘sever the link between sex and long-term intimacy and allow the performance of undomesticated sexualities that challenge common prescriptions of feminine passivity’ (ibid., p. 221). What, she asks, ‘do we make of sex workers who are, effectively, domesticated?’ (ibid., p. 221). She cites national studies from India in the present that show that for 32 per cent of prostituted women ‘kith and kin’ were responsible for their entry into prostitution, and that 82 per cent of prostituted women in Bombay have and raise children in brothels. Precisely similar family structures exist in Calcutta’s brothels too, she points out. Many prostituted women remain in brothels because they have been born there. In her historical study she found that husbands and mothers delivered girls and women to brothels. Brothel keepers adopted maternal roles towards the girls delivered to them. Family members put girls into prostitution through the devadasi system, and in castes that traditionally practised ‘entertainment’ for their livelihood, girls and women supported whole families through prostitution combined with dancing and music. Tambe ‘cautions against’ the celebration of the ‘liberatory potential of sex work and brothel life’ and is critical of ‘sex radicals’ who say that ‘sex work can be a source of agency and resistance’ (ibid., p. 236–7).

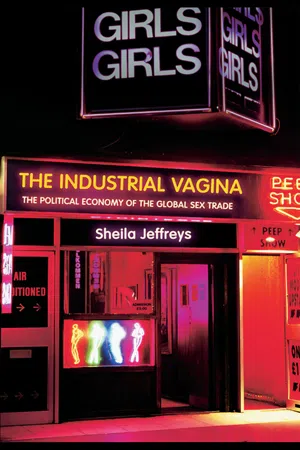

But Kapur goes further in her romanticization of prostitution, stating that the agency of the women that the anti-violence perspective turns into ‘victims’ is ‘located in the recognition that the post-colonial subject can and does dance, across the shaky edifice of gender and culture, bringing to this project the possibility of imagining a more transformative and inclusive politics’ (Kapur, 2002, p. 37). In her laudatory commentary on Kapur’s work, Jane Scoular makes the basis of this approach, which she identifies as ‘postmodern’, plain. She says such theorizing, ‘by maintaining a critical distance from oppressive structural factors’, enables theorists ‘to resist attempts to see power as overwhelming and consuming the subject’, thus creating space for a ‘transformative’ feminist theory which seeks to ‘utilize the disruptive potential of the counter-hegemonic and “resisting” subject to challenge hierarchical relations’ (Scoular, 2004, p. 352). If power relations are downplayed, then it is easier to see prostituted women as ‘dancing’. In contrast, The Industrial Vagina is diametrically opposed to the idea of keeping a distance from ‘structural factors’ that underlie prostitution; rather, I seek to make them more visible.

Kapur’s approach is echoed in the work of Jo Doezema, who argues that ‘western’ feminists victimize Third World prostituted women (Doezema, 2001). She too is savagely critical of the work of feminist anti-trafficking campaigners such as Kathleen Barry and the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW), accusing them of what she calls ‘neo-colonialism’ in their attitude to Third World prostituted women (ibid.). She says that the attitude ‘that Third World women – ...