- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools for Transforming Trauma

About this book

Tools for Transforming Trauma provides clinicians with an integrative framework that covers a wide range of therapeutic modalities and a "black bag" full of therapeutic tools for healing trauma patients.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

Understanding How Trauma Leads to PTSD

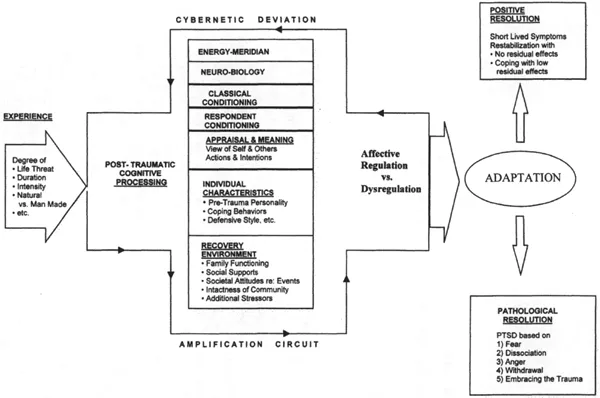

In order to be able to help clients transform trauma, it is important to understand how trauma affects people. A traumatic or stressful event does not necessarily lead to formal post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or to other trauma-based psychological problems. The process that creates this change is highly dynamic. There are many interactions with many variables. The person is the passive recipient of certain events, and at the same time is never truly passive, but rather always actively processing information, creating responses, and creating meaning. The process occurs over time. The time involved can be on the microlevel of the time it takes to process visual stimuli and develop an immediate cognitive appraisal of danger. Or the time involved can be on a macrolevel consisting of days, months, or years in developing a view of self and other, creating behavioral patterns, and so on. The process is depicted in Figure 1. The figure does not adequately depict the time dimension.

If we look at the extreme left of the figure, we see that some type of traumatic event happens. If we look at the right-hand side, we see the end of the process. We see that there are two possible directions that a given person can eventually take. In one direction, the person will eventually have a positive resolution either with no residual effects or coping well with any effects that do occur. Optimally, the person’s life remains rich. In the other direction, a person has a poor adaptation in which there are many symptoms and in which the person’s life becomes impoverished and/or focused in one of several limiting manners.

Figure 1.1. Eco-systemic model of PTSD.

We will spend the rest of this chapter looking at what happens in between the precipitating event(s) and the resolution to learn how one path is chosen over another. A thorough understanding of all of the different interactive elements that create PTSD will allow us to design different tools to help transform a negative resolution into a positive one.

The nature of the traumatic event(s) does have a significant impact. First, the duration and intensity of the event or events matters a great deal. A single event of childhood sexual abuse can have tremendous effects. However, years of repeated sexual abuse will have a far greater impact, all other things being equal.1 Being held captive for a day in jail is likely to be less traumatic than being held captive in a Nazi death camp for a year. All things being equal, the longer and more intense the experience, the more likely it will be to overwhelm the individual’s ability to cope, resulting in greater PTSD. If a person perceives the likelihood of serious injury or death, there is a far greater likelihood of PTSD developing (Kilpatrick et al., 1989). If the traumatic incident is perceived as natural and without malicious intent or manmade negligence, it is less likely to lead to PTSD. Quarantelli (1985) has noted that survivors of natural disasters such as hurricanes and tornadoes do not have relatively high levels of PTSD given the amount of devastation. If abuse is inflicted with sadistic intent, it will tend to create different reactions in the victim than if the intent were nonsadistic (Salter, 1995).

Big “T” and Little “t” Traumas

This is a good point to discuss the difference between “big T” traumas and “little t” traumas. Big T traumas all meet the criteria in the DSM (APA, 1980, 1994) for PTSD. They include violent attacks, rape, war, and so on. A little t trauma is any event that is beyond a person’s ability to master at the time of the event. It can be something as simple as a child getting lost for a few minutes, or a child being overwhelmed with fear after a nightmare and no one comforting the child. These little t traumas often are left unprocessed in the unconscious. They create areas of vulnerability that become part of a negative spiral when a Big T trauma occurs. In the case of a major trauma, the person may be able to stand the impact of the main event. However, he may be so weakened that it is a small t trauma that finally collapses his coping abilities. For instance, when I recently watched the movie Saving Private Ryan, I was barely able to stand the first 30 minutes when the soldiers attacked Normandy. This was not to be the scene that haunted me. It was the scene where the Nazi slowly kills one of the soldiers in a knife fight while “hushing” the man like you would a baby. This was more than I could take. There was something about the smallness of this event (compared to the massive trauma of the assault on the beach) that allowed the trauma to get through. Some of these small t traumas are inevitable in life. When caretakers allow too many of these small t traumas to occur, neglect is present.

The Role of Neglect

The role of neglect is often underrated in working with trauma and abuse. If a person is raped as an adult or sexually or physically abused as a child, it is easy to point to “The TRAUMA.” These are capital T traumas. But, it is often the shear number of small t traumas in a neglectful family that can create such havoc. (This is not a legal definition of childhood neglect, which usually includes lack of appropriate physical care.) In many cases, therapists as well as clients pay too much attention to the big T traumas because they are easy to identify. In many cases it was the neglect or the acts of omission that individually or cumulatively caused so much dysfunction.

Neglect forces a child to attempt to self-regulate before the child is able to do so effectively. Therefore, the child will become overwhelmed, perhaps chronically so. The child will be forced to make adaptations, such as increased use of dissociation and denial. The child will make certain assumptions verbally or preverbally about the nature of the world. There is evidence that neglect may lead to actual brain changes that may make it more difficult to self-regulate later in life.

Neglect also means that the child will probably not learn more successful and adaptive coping strategies. Nor will the child have effective internal representations (states of consciousness, SoCs) of love and positive affect to call upon in times of stress. Children who have histories of significant to extreme abuse by definition live in families that are highly dysfunctional. It is not just the events of abuse that occurred. These families “neglect” to teach their children adaptive coping strategies or belief systems. There are almost always huge problems with boundaries. For instance, the child is often made to feel it is his or her fault that the abuse occurred. Some of this belief comes from the developmental egocentricity of the child. But oftentimes, the child is told this directly and indirectly. These children are almost always deprived of loving, warm, and safe interpersonal transactions. It is not just that you were raped as a child, it is that very few times were you hugged or told “I love you” (without it leading to some abuse).

Once an external event happens to a person, that person must process it. Technically, we can speak of the event from an external perspective, such as, “A yellow car traveling at 35 miles per hour impacted a green car traveling at 10 miles per hour at an angle of 25 degrees at 9:15 a.m. on Tuesday, April 22, 1998.” We can speak of specific physical injuries and so on. These are so-called objective facts. However, from the perspective of the people in the car, we cannot speak about the accident as an external event independent of their processing.

Over time the person must process the experience and all of its ramifications. Horowitz (1986) has described this process as a cognitive information model. He suggested that the main reason for the phenomenon of intrusion of traumatic symptoms (e.g., flashbacks) is that the individual keeps trying to think about the event to understand and process the event. During those times the brain is attempting to assimilate the experience. If during the process the person becomes overwhelmed again, the cycle shifts and the person moves into a numbing phase. The cycle continues until the traumatic experience has been assimilated. The problem is that many times this never happens. In more severe cases it would be more accurate to say that instead of the person assimilating the trauma, the trauma assimilates the person.

As the post-traumatic cognitive processing is occurring, a parallel process occurs in the affective system. Part of the overwhelming nature of the trauma is that the person is flooded with intense affect. Fear states are the main feeling. This can include fright, anxiety, panic, and terror. Other common affects are helplessness, shame, anger, guilt, and grief. The person attempts to regulate the amount of affect and feeling they are having. The more a person can maintain a connection to positive or resourceful feeling states, the more they can cognitively process the event.

For example, Michael lives through a devastating hurricane. His house is destroyed and he and his family are almost killed. He feels intense fear as he remembers the event. He feels grief that he has lost his house. He feels even more fear and helplessness as he ponders the possibility that everyone he loved could have been killed. So his unconscious mind begins to search for something resourceful and positive to help regulate the feelings as well as process the event. He thinks about other difficult challenges he has overcome and feels some pride and mastery. He reflects on how he did certain things during the storm that were helpful and feels some decrease in helplessness. He attends to the fact that this happened to his entire community and knows he is not alone in this, so he feels some belonging. He also remembers his connection to God and is grateful that no one got hurt, so he begins to feel safe and loved. In this manner his affect is regulated so that he can continue to process the experience.

The affect itself is one additional variable that must also be processed cognitively. To put it simply, people often have fear after a trauma. The person must make sense of this feeling. In the example of Michael, it seemed perfectly normal to him that he felt fear. Everyone else felt fear. The entire community was demolished. Furthermore, the entire country was galvanized to help. So there was no loss of face for having fearful reactions in the face of such devastation. Let us quickly compare this to a child who is being sexually abused by her father at night. She also has intense fear. But when she comes downstairs the next morning and everything seems perfectly normal, her fear now does not make so much sense to her. She begins to doubt herself. Every person I have ever seen who has not adjusted well after a car accident is always tremendously upset about his or her emotional reactions to the car crash. They are traumatized by the fear they felt postcrash.

To summarize to this point, during and after any novel event, a person has some emotional reaction to the event and must make sense of the event. The affective regulation and cognitive processing systems work interactively to achieve this goal. Traumatic events are traumatic because they tax and overwhelm the parameters of this system. The system will eventually adapt. One path of adaptation is healthy; the other adaptation is unhealthy. We now move to the variables that affect this outcome.

The single biggest factor in how a person adjusts to a traumatic event is the recovery environment. The recovery environment includes the amount of social support a person has, the reactions of the family, the reactions and intactness of the community, societal attitudes, and the responses of helping professionals (doctors, Red Cross, police, courts, etc.). To put it simply, the more these variables help soothe and comfort the person (regulate affect) and help the person stay connected to positive and resourceful contexts, the more adaptive the resolution is likely to become.

On the other hand, the recovery environment is the arena where a person can also be hit with any number of small t traumas. The individual is especially vulnerable. His or her shields are down. A relatively small problem can do serious damage. I have repeatedly worked with people whose symptoms were not tied to the actual incident, whether that was an accident or rape. Rather, it was something that someone said to them in the emergency room. Or, it was something that a police offer said when questioning the person that haunts him or her. With abuse cases, it is often a small t event that is so hurtful psychologically.

When Vietnam vets came home, they were not welcomed as heroes. They were treated as villains and baby killers. World War II veterans were treated as heroes. This difference in the recovery environment was a huge factor in some Vietnam vets’ poor adjustment to coming home.

Paradoxically, a small gesture of support and kindness at these times of vulnerability can make a world of difference. For instance, Tom had been in a serious auto accident and had lost his arm. As he was entering the emergency room, a nurse came up to him and talked to him in a very soothing voice. He reported that she said, “I know you are scared. That is completely normal. We are going to make you comfortable. We are going to take good care of you. The surgeons will try to reattach it. Let your body relax. That will help the surgeons. Let your body know that you are safe. Everything will work out for the best.” Tom reported that this event is the one thing that he clearly remembered in the blur. He also reported that he did in fact calm down. He stated that he had a task to do in order to help the doctors, so his perceived helplessness lessened. In fact, the doctors could not save his arm. While this did cause Tom some psychological issues, he often thought of the nurse and what she had said. It always was a comfort.

Trauma cascade refers to the fact that traumatic events do not just happen to individuals but to their families as well. In some circumstances, the effects of the traumatic event(s) spread from family member to family member, creating a cascade of increasing trauma and decreasing resourcefulness. This phenomenon often occurs in traumatic deaths of children. Each individual in the family is affected and reacts poorly, which further stresses other family members. Parents begin to fight and blame each other instead of supporting each other, and so on. Another example is in the case of rape. A husband or father may be unable to get a picture of the rape out of his mind. He reacts with rage at the perpetrator. He is not able to manage his feelings. He is not able to be supportive to the rape victim, who then becomes more upset. In some cases, he may even act out and attempt to kill the perpetrator, which places him in legal trouble, and so on.

Nowhere is the impact of a poor recovery environment seen more clearly than in the case of long-term incest. In the best-case scenario, the child is induced to have sex at various times, while at other times the family is “loving” and acts as ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Understanding How Trauma Leads to PTSD

- 2 A Neo-Ericksonian Framework for Treating Trauma

- 3 The Tools Framework

- 4 Tools for Safety, Ego Support, and Ego Growth

- 5 Tools for Transforming Traumatic Memory

- 6 The Use of Thought Field Therapy in Treating Trauma

- 7 Tools for the Holistic Self

- 8 If You Meet the “Tool” on the Road, Leave It! Person-of-the-Therapist Issues

- Integration and Summary: Beyond Tools and Trauma

- Epilogue: Tools for Transforming Terrorism

- References

- Index

- Other Resources

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tools for Transforming Trauma by Robert Schwarz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Emotions in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.