eBook - ePub

Her Husband was a Woman!

Women's Gender-Crossing in Modern British Popular Culture

This is a test

- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Tracking the changing representation of female gender-crossing in the press, this text breaks new ground to reveal findings where both desire between women and cross-gender identification are understood.

Her Husband was a Woman! exposes real-life case studies from the British tabloids of women who successfully passed as men in everyday life, perhaps marrying other women or fighting for their country. Oram revises assumptions about the history of modern gender and sexual identities, especially lesbianism and transsexuality.

This book provides a fascinating resource for researchers and students, grounding the concepts of gender performativity, lesbian and queer identities in a broadly-based survey of the historical evidence.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Her Husband was a Woman! by Alison Oram in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

1900-late 1920s

The traditions of gender-crossing

1 Work and war

Masculinity, gender relations and the passing woman

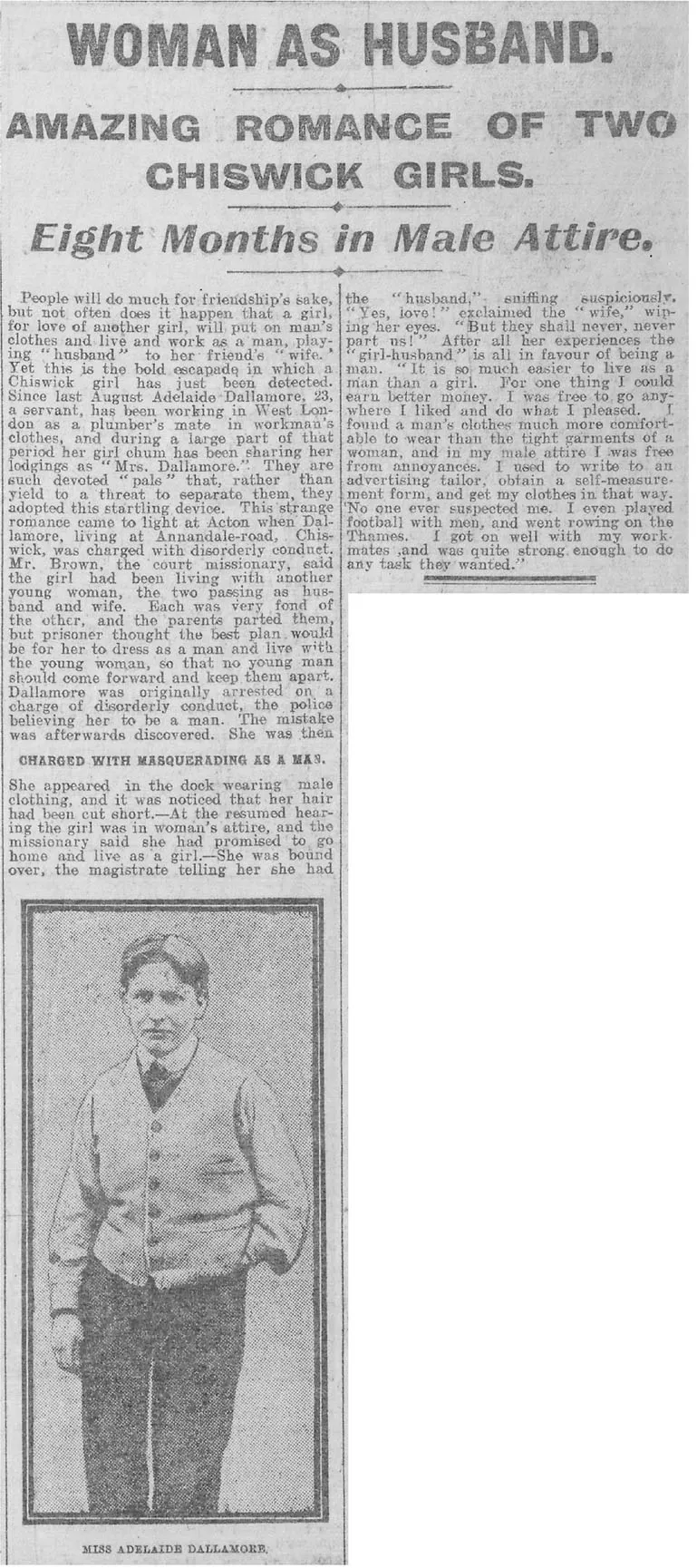

In 1912, the News of the World devoted three headlines, two columns and a photograph to

the bold escapade in which a Chiswick girl has just been detected. Since last August Adelaide Dallamore, 23, a servant, has been working in West London as a plumber’s mate in workman’s clothes, and during a large part of that period her girl chum has been sharing her lodgings as ‘Mrs Dallamore’ (see Figure 2).1

This report is a classic example of early twentieth-century cross-dressing stories – the ‘bold escapade’, the typical masculine working-class occupation, and the relationship with another woman. Press stories always pursued detailed descriptions of the ‘man–woman’s’ appearance – height, build and facial hair – and assessed her social performance as a man – strength and skill in masculine work, appropriate leisure pursuits such as drinking and smoking, and courtship and marriage with women. The first half of this chapter will show that each of these themes continued to be important in press reporting between the 1900s and the late 1920s and beyond, suggesting that these were core elements in the contemporary understanding of masculinity. These stories of passing women are really about the performance of gender in daily life. How cross-dressed women acted and were judged as men demonstrates the ways in which masculinities are continually contrived in various everyday settings and relationships and how the mirage of masculinity was produced, not only by those who were passing as men yet had female bodies, but also for biological men engaged in the process of constantly reinventing manliness. Cross-dressing women were both disruptive and respectable. Newspapers represented them as exciting, sensational figures, yet applauded them for successfully following what were quite conservative ideals of masculine behaviour. Within a familiar story formula they were safely entertaining, yet sowed the seeds of the insurrectionary idea that gender was not innate but a social sham.

The early twentieth century was a time of transition and crisis in masculinity and femininity. The second part of this chapter shows how the cross-dressing story was also a means of exploring feminist challenge and the disruption of gender

Figure 2 Adelaide Dallamore. News of the World, 7 April 1912, p. 9.

Reproduced with the permission of the British Library.

certainties during the years of suffrage agitation, the First World War and postwar social consolidation in the 1920s. It is striking, however, that despite considerable social changes, there are significant story-telling continuities in the representation of passing women in these decades.

Appearance, clothing and the equivocal body

Masculine gender is established in two interconnected ways. It is expressed physically through body management and also in social interaction with other people, with other men at work or during leisure, with women and in the family.2 In the press stories both these layers are keenly examined: the ‘look’ of the masculine and the acting out of social masculinity. The stories were always presented as entertaining and constructed with humour. They often explicitly drew on the reader’s familiarity with male impersonation on stage, offering complex and frequently contradictory messages about the very nature of gender.

Women’s and men’s clothing was so distinctly gendered in this period that abandoning skirts and adopting trousers and short hair was a crucial step towards acceptance as a man. What people wore was central to how they were read by others, not only for their gender but also for their age, class and occupational status. The press was obsessed with the physical appearance and clothing of cross-dressing women. The photograph of Adelaide Dallamore published by the News of the World in 1912 showed her to be a convincing young man. The paper described her as ‘a good-looking girl, sturdy, and rather short of stature. Dressed in workmen’s clothes, with her smooth, boyish face and rather low-pitched voice, she would easily pass as a young man.’ Dallamore had obtained men’s clothes by mail order from an advertising tailor. After work she would exchange her working clothes ‘for a better suit’ and her soft collar ‘for a hard “stick-up” one’ and go out for walks arm-in-arm with her wife.3 In another case, Paul Downing, a black American, was arrested in London in 1905 after working as a farm labourer in Kent. Unlike many of the other passing women, Paul Downing was described as tall and strong: ‘A huge negress . . . of powerful build’.4 The perception of Downing as a man was aided by contemporary racial stereotyping of black people in terms of their physicality and capacity for hard manual labour. ‘“Paul Downing” was a striking figure – a woman over 6ft in height, and of magnificent physique, with a not unpleasant face and fine teeth.’5

The newspaper photographs of the short cropped hair, the confident boyish face and the man’s suit of the passing woman, the spectatorial effect underlined by her masculine stance, gesture and accessories such as cigarettes, echoed the publicity postcards of popular male impersonators on stage. The descriptions, too, recall those made of male impersonators. Ernest Wood, a young Soho waiter discovered to be a woman after her death in 1924, was said to dress ‘immaculately’ in fashionably cut clothes when off duty: ‘She was very proud of her appearance, and when walking looked a positive dandy.’6 The reports of Paul Downing framed her appearance in terms of blackface minstrel entertainment. ‘She has a coal-black complexion, dazzling white teeth, is well built, and has a very pleasant manner.’7 Both kinds of gender-crosser were assessed for their competence at mimicking masculinity.

Yet the cross-dressing story was crucially different to stage impersonation. Its sensationalism lay in the fact that this performance of gender had gone undetected. The music hall male impersonator was judged on her capacity to imitate masculinity at the time of her performance, in the full knowledge that she was a woman. Hetty King’s skill at crossing gender was relished by the audience and her peers: ‘Old pros, who had seen the lady over the years, have raved to me about her painstaking, perfect portrayals of the characters she created for her songs: the man about town, the down and out, the army sergeant.’8 Male impersonators’ performance of masculinity was precisely defined and often caustically observed; in some acts it was overblown and comically exaggerated. Real life cross-dressers, on the other hand, aimed to pass so well they would go unnoticed, their masquerade more of a homage to masculinity.

Reviewers emphasised this contrast between the performer’s gender and her skill in male costume, an approach which could work to secure the idea of innate gender difference. The press was always willing to help Vesta Tilley construct her image as the best-ever male impersonator alongside her genteel, feminine and irreproachable private life as Mrs Walter (later Lady) de Frece. While ‘delightful . . . to look upon in her male attire, those who have the privilege of her friendship know that she is even more delightful to look upon when attired in the garb of the sex which she may truly be said to adorn’ declared the News of the World’s reviewer in 1919.9

Male impersonation had multiple and sometimes contradictory effects. It suggested the social construction of gender, as artists displayed their skill at performing masculinity down to the last gesture. Yet while the inversion of gender and the parodying of masculinity challenged audience assumptions, it was, through the ubiquity of the genre, also normalised. J. S. Bratton argues that the boundaries of male impersonation were increasingly policed in the early twentieth century, as reviews emphasised performers’ smart and feminised appearance using terms such as ‘dainty’ and ‘dapper’.10 Male impersonators might be unsettling in their gender-crossing, but the music hall context stressed their theatrical skills and the woman underneath.

Both the male impersonator on stage and the cross-dressing woman on the street were consciously and deliberately performing gender. But in her successful and undetected mimicry, the cross-dressing woman undermines the idea of essential gender difference. Her masculinity was not a product of biological maleness, nor presented as theatrical artifice. Because she takes in the people around her with a few authoritative tricks, she reveals to the reader the taken-for-granted daily staging of masculinity by all men, the normally hidden reiteration of ‘performative' gender.11 Hegemonic masculinity seemed to rest on a slim thread indeed (and have little relationship to the sexed body) if these slight, short men, who lacked facial hair, could be accepted in the daily relationships with workmates and neighbours familiar to many readers, over months and years.

The sensational nature of the cross-dressing story rested on this troubling knowledge. Alarm at this dissonance between the sexed body and the appearance of gender was instantly transmuted into an entertaining puzzle for the reader. Which aspects of appearance or behaviour might or should have revealed ‘true’ gender sooner than they did to those around the passing woman? The stories tried to contain the implications of cross-dressing, both by asserting that ‘true’ sex would somehow always find its way out, and by dragging women’s cross-dressing firmly back to the relative security of the theatrical frame of reference, belatedly assessing her past performance of masculinity.

The occasional story tried to emphasise the ‘really a woman’ element, rather like the on and off stage performance, implying that cross-dressing was very difficult and contrary to a woman’s feminine instinct. Some newspapers told the tale that Charlie Richardson, discovered on her death in 1923 to be Annie Miller, had rented a separate room in which she had kept her women’s clothes and went back there sometimes to wear them. The People used this as the twist for its headline: ‘Astounding Masquerade Revealed by Death: Woman in One Neighbourhood – Man in Another’.12 Other stories used the language of the stage more explicitly, explaining cross-dressing as a talent for acting. In 1910 Dorothy Morgan, a runaway girl of 15, ‘masquerading as a youth . . . was found in the train dressed in boy’s clothing, and seems to have essayed to play the part very completely’.13 A London story from 1926 told how a 22-year-old woman dressed as a man was accused of attempted arson after being found in the garden of a house. Rose Edith Smith, it transpired, was a theatre attendant from Vauxhall. ‘Her face was covered in grease-paint, while a moustache had been “lined” in with soot.’14 Theatrical terminology signalled that cross-dressing was to be judged by the tenets of the theatre – the skill of the performance, the success of the pose, the humorous qualities of the account. Presented as entertainment, the qualities of sensation and display to be enjoyed, the disguise to be marvelled at, the act of gender-crossing was not to be taken entirely seriously and its implications for the making of gender were thus avoided. It is a diversion, a mere ‘escapade’, as the language of the press headlines reiterated time and again. Even breaking the law is secondary to the main show of the passing woman as star performer in a human-interest drama. The cross-dresser is lent the protection of the performer, the joker, giving her licence to perform outside the boundary of the theatre.

Yet the more stories emphasised theatrical skill, the more evident it becomes that gender can be unravelled and is not an essential quality possessed by the body. The 1910 story of Elena Smith, who had passed as a man in New York for five years, demonstrates this double bind. ‘Mrs Smith disguised herself as a man in order to win a wager that any woman possessed of histrionic talent could pass unsuspected as a member of the opposite sex.’ Working as a businessman and living the life of a man about town (unusually for a cross-dresser, and more like a stage male impersonator), she ‘was constantly at theatres, music-halls, restaurants, races, saloon bars, and even boxing bouts’. Exposing the everyday performativity of gender, Elena Smith said she wanted ‘to laugh at both sexes for their shallow, artificial tricks and insincerities’ (though she expounded at length on the egotistical and self-centred character of most men).15

Gentle humour was a recurring stylistic device in these accounts. Humour, like the theatre and the telling of stories, creates a sanctioned public space to lightheartedly explore what may otherwise be difficult and disturbing topics such as gender, class and sexuality.16 Comedy and laughter can work to dissipate unease around ‘strange’ behaviours and relationships, while retaining a narrative about this potentially disruptive knowledge. Joking drew attention to the realisation that faking gender was easy, while diffusing anxiety about this knowledge. In the interview with Adelaide Dallamore and her wife Jessie Mann a comic tone develops with some light-hearted exchanges between the two girls about Adelaide’s men’s clothes. ‘“Do you remember what an awful job we had tying your first necktie?” The girl plumber burst out laughing at the recollection’, and explained that it had taken an hour and a half to get it tied properly.17 The reported laughter signals to the reader that this is a funny story about the comedy of dressing up and the inversion of gender. The boundaries between male and female clothing styles are so tightly drawn that young women would have no idea how to knot a tie. Yet it also shows that, just like the male impersonator, they can learn how to do so. Gender boundaries are not so impermeable and with a little practice it is easy to pass for the opposite sex by exploiting the everyday presumption that gender is aligned with dress.

As in music hall, comic postcards, funny stories or everyday jokes, stock elements of humour were developed in the cross-dressing stories. There was repeated verbal humour around how to speak of the passing woman, and play with gender pronouns: the classic comment being ‘I still cannot call him “she”.’18 The equivocal body provided various jokes. A perennial focus on the beardlessness of the passing woman appears in the story of Annie Miller or Charlie Richardson in 1923. The local barber told the News of the World:

I remember now that she had little hair to shave. There were a few bristles on the upper lip, and some fluff on the chin . . . One afternoon when she came in, a customer suggested that they should toss who should pay for two shaves. ‘Charlie’ agreed and won. She was delighted, and passed the remark that she had suddenly become lucky.19

The responses of the participants –...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: sex, scandal and the popular press

- Part I 1900-late 1920s The traditions of gender-crossing

- Part II The 1930s Entertaining modernity

- Part III Gender and sexual identities since the 1940s

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index