![]()

1

The Tall Building Typology

The confluence of a number of economic, social and technological innovations at the end of the nineteenth century in the USA spurred the development of the tall building. Up to that point, the tallest buildings in cities were either religious buildings such as churches or temples, palaces of the nobility or connected to defence (Kostoff, 2001). Since that time, however, a number of distinct periods of tall building development have occurred as a result of different sets of drivers. This chapter examines the challenge of tall buildings, looking specifically at the evolution of tall buildings, responses to them in particular places and the potential range of tall building impacts. It explores the evolution of the tall building using a number of cities and buildings to exemplify responses to tall buildings during specific periods and in particular locations, and is sub-divided into the following sub-sections: the emergence of the tall building; the modern movement and tall buildings; the post-modernist backlash; and the global tall building phenomenon.

The emergence of the tall building as an architectural form has been a feature of the twentieth century city (Bradford Landau and Condit, 1996). Likewise, responses to the development of tall buildings have characterised urban planning during this period. As well as the design and appearance of the buildings themselves, the urban planning implication of building tall started to be articulated from the end of the nineteenth century onwards. Goldberger (1981) outlines that at the start of the twentieth century it was beginning to be understood that tall buildings were fundamentally different to what had been built before, and that they demanded a different set of attitudes towards the making of cities. The following sections use the examples of New York City, Paris, Houston and Shanghai to assist in understanding the drivers, impacts and responses to tall buildings during their evolution.

The Emergence of the Tall Building

The evolution of the tall building has been punctuated by a series of technological innovations that have fuelled their development since their inception in the USA in the late nineteenth century. Webster (1959) suggests that the tall building typology would not have evolved without unique favourable conditions. Firstly, he outlines economic conditions: as the emerging cities of the USA developed, demand for land in central areas led landowners to seek to maximise their profits by demanding ever more intense development (Webster, 1959; Kostoff, 2001). This has been a characteristic of tall buildings ever since; they are a way of increasing the amount of saleable or rentable floor space of a plot in order to maximise returns to the landowner. Secondly, the nature of land ownership in many cities in the USA at that time meant that plots were small or fragmented, requiring innovative solutions for development in order to realise profits on individual sites (Bradford Landau and Condit, 1996). Finally, the availability of capital contributed to the evolution of the tall building in that it provided significant amounts of money to both experiment with built forms and to portray the wealth of individuals and corporations. Critics such as Abel (2003) and Kostoff (2001) indicate that tall buildings often represent excessive money and power and the erosion of traditional values. Furthermore, it has been argued that tall buildings can either declare to the world that there is a strong economy where tall buildings develop, or that there is economic confidence in a particular location (House of Commons, 2002). For contemporary tall building projects to come to fruition there is a requirement that an occupier for a significant amount of the internal space is found, meaning that market confidence in the location of new tall buildings is crucial to the success of such projects (Sudjic, 2005, Sudjic, 1993).

Webster outlines the technological conditions that allow tall buildings to evolve. He distinguishes these from the means (structural and material conditions) outlined above and specifically refers to the availability of suitable tools, building processes, sources of power, plumbing, heating, air conditioning and so on, as being crucial to the evolution of the tall building. The necessary synthesis of these technological developments is often overlooked as they are not readily visible yet are crucial to the successful completion of tall buildings.

The evolution of this new built form at the beginning of the twentieth century resulted in a new set of challenges for planning, regarding the impacts of tall building in particular places, how the impact of such buildings could be managed through existing or new regulatory mechanisms, and finally, how this regulation could be incorporated within decision-making processes. Furthermore, the unique challenges posed by building tall were magnified in situations where built heritage and character of place were relevant, necessitating the evolution of regulatory tools designed to protect buildings and townscapes of historic or architectural significance.

The first quarter of the twentieth century saw the evolution of the skyscraper as a distinctly American invention, providing much needed office space to overcrowded and rapidly growing cities. The debates around the impacts of such buildings related mainly to the concerns of light and shadow, impact on neigh-bouring buildings, the health and safety of occupants, and the transport of large numbers of workers to and from such buildings.

This phase of the evolution of tall buildings, and responses to them, was distinctive to North America (Goldberger, 1981) (see Figure 1.1). At that time unique conditions in the USA saw the invention of the iron frame that proved pivotal in assisting buildings to grow taller. This displaced solid, load-bearing walls with an interior metal frame utilising technology borrowed from bridge building (Hall, 1998). Furthermore, when used with the iron frame structure, a curtain wall could be made of thinly-cut stone, glass or metal thereby opening up opportunities for dressing buildings. Finally, the development of the Otis mechanical lift, in 1880, facilitated a great range of building heights (Abel, 2003). Other innovations – from the replacement of the iron frame in the early twentieth century by the use of both rolled steel and reinforced concrete (which expand and contract at the same rates and bond to steel extremely well), to current technological innovations in sustainable building forms – are resulting in the potential for taller buildings with unique forms (Webster, 1959; Yeang, 2002).

Figure 1.1 The Chicago skyline

New York City and the Zoning Response to Skyscrapers

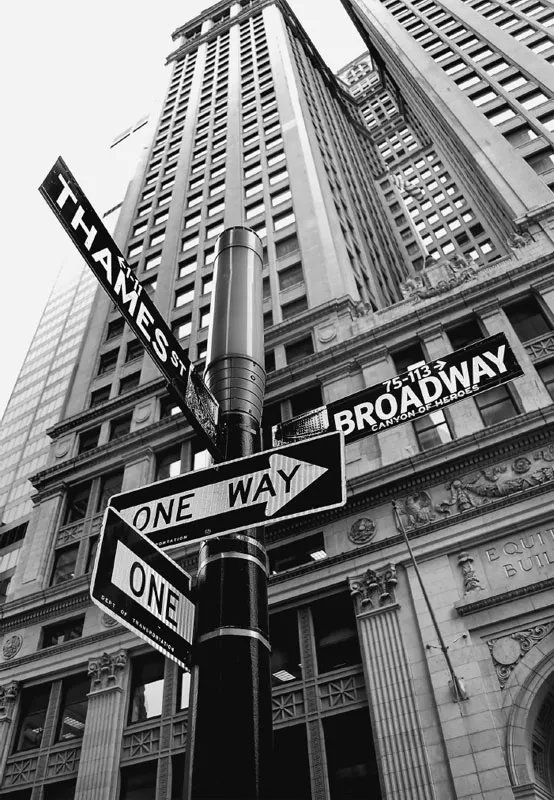

The example of New York City, regarding the emergence of the tall building, is useful in seeking to articulate responses to this new form of building at a certain point in time. A palpable rivalry developed between Chicago and New York City at the turn of the twentieth century, which manifested itself in competitive battles for the tallest building in the world. The beginning of the new century saw New York City predominate for many years, as the city absorbed expanding corporations requiring more efficient workspace and more prestigious headquarters (Hall, 1998). Goldberger (1981) defines two forms of skyscraper that evolved in New York City separate from the Chicago skyscraper style: those which were theatrical, built for sheer visual pleasure and those which were conduits for making money, “systems for building rentable floors in the air” (p. 26). The development of the skyscraper in New York City was, however, ten years behind Chicago, and it borrowed from the techniques that were pioneered and employed there (Watkins, 2000). The city was a more conservative environment than Chicago in which a rigid building code operated, limiting the height and massing of buildings on a tight grid-iron street pattern. Only after building techniques had been tried and tested in Chicago were they utilised in New York City. Hall (1998) postulates that the tall buildings built in the city were mostly commissions from particular corporations, rather than speculative developments like those in Chicago. New York City skyscrapers were the result of two great periods of building, one from 1892 to 1914 and the other in the 1920s (Hall, 1998). The first period brought together the new technologies pioneered in Chicago whilst the second period reflected the burgeoning commercial role of the city in the USA. Artistic expression flourished in the city and the new skyscrapers borrowed strongly from existing architectural genres. The skyline of the city began to rise as a result of growth in the city’s economy (see Figure 1.2). Tall buildings were the new symbols of corporate power and were built “to be seen” (Domosh in Hall, 1998: 774).

Figure 1.2 The Flatiron building, New York City

As a result of the increasing height of building in the city, a group of concerned citizens formed calling themselves the Committee on Congestion of Population in New York to lobby the City Building Commission about the perceived impacts of these buildings. A report issued in 1913 by the Committee has been recognised as the blueprint for the zoning regulations of 1916. Namier (1931) indicates that in the USA skyscrapers had, up to this point, related to and reflected human form, representing “vertical streets that have risen to their feet and stand upright like human beings” (p. 7). The erection of the Equitable Building in 1916 (see Figure 1.3) however, showed how such buildings could dominate the environment and negatively impact upon the way in which people lived. The neo-Renaissance building occupying the whole block, rising in two masses above the base and connected by a wing for the building’s whole height, forms a giant letter “H” when viewed from above (Abel, 2003). The building is tall but not slender like many of its contemporaries (Kitt-Chappell, 1990).

Figure 1.3 The Equitable building, New York City

The Equitable Building had a profound impact upon the way in which people viewed tall buildings in the city, it was said to block ventilation of the surrounding streets, deposit 13,000 workers onto already overloaded pavements, roads and subways, and create a problem for fire-fighting. Furthermore, the building was said to cast a shadow six times the size of itself at noon and it visually dominated the surrounding streets (Kitt-Chappell, 1990). The Equitable Building, in essence, became a whipping-boy for the political lobby which supported some sort of building height control in the city, even though it was not one of the tallest buildings in the city at that time. It is apparent, in hindsight, that the building did pioneer both lift design and building management, but also that it became a necessary scapegoat in the passing of the zoning regulations in 1916.

The 1916 zoning regulations, drafted in advance of the completion of the Equitable Building, required tall buildings to be set-back to allow sufficient daylight to reach the streets and adjacent buildings. Many subsequent landmark buildings such as the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building owe their distinctive shape to the impact of this building and these zoning laws, although the new style could be seen to be an evolution of the type exemplified by the Singer Building.

The Modern Movement and Tall Buildings

The development of the American skyscraper in the early twentieth century was followed by the development of a distinct phase of tall building promoted by the modern movement. Also known as the International Style, modernism was a major architectural trend in the 1920s, mainly influenced by German and Dutch movements such as Bauhaus, de Stijl and Deutscher Werkbund, which all rejected tradition and revelled in radicalised ideas of the future (Webster, 1959). The movement’s goal was a rational, even scientific, approach to art and architecture, informed in part by a popular view of evolution, namely that progress toward a perfected world was inevitable, making the past obsolete (Lampugnani, 1983). The particular importance of tall buildings in the modern movement was evident from the initial ideas of architects who believed that the form of buildings should follow their function. Lampugnani (1983) outlines a number of attributes of this movement which can be termed the “machine aesthetic”: a radical simplification of built form; the rejection of ornament; the use of “modern” materials such as glass, concrete and steel; the literal transparency of buildings (reflecting an open public view of traditionally private space); the rationalisation of space and a reliance on industrial mass production in buildings (see Figure 1.4). Architects such as Le Corbusier and van der Rohe experimented with new styles for housing and offices at this time.

Figure 1.4 Lake Point Tower, Chicago

Le Corbusier’s “Plan Voisin” for Paris, for example, took the removal of historicism from architecture to new lengths, proposing an urban planning solution to the perceived chaos of the old city on the right bank (see Figure 1.5). Instead of the beauty of the city of Paris, he proposed row after row of identical skyscrapers to replace the historic fabric of the city, a veritable skyscraper park. Interestingly, the main impacts of this movement were felt after the Second World War when the legacy of Le Corbusier’s work and the production of new iconic buildings by van der Rohe, amongst others, stimulated the wholesale adoption of modernist principles in architecture and urban planning. Modern movement ideas represented the “bold … mystical rationality of a generation that was eager to accept the scientific spirit of the twentieth century on its own terms and to throw off all pre-existing ties – political, cultural, conceptual – with what was considered an exhausted, outmoded past” (LeGates and Stout, 2003: 317). Furthermore, for the first time, other uses apart from offices were suggested for tall buildings, most notably as dwellings. The main impacts of this movement were felt after the Second World War, when its legacy stimulated the wholesale adoption of modernist principles in architecture and urban planning. Buildings inspired by modernist ideas were built across the globe.

Figure 1.5 Le Corbusier’s “Plan Voisin”

The towers of glass proposed by the modern movement were both radical and contemporary, reflecting advances in tall building engineering that cr...