![]()

CHAPTER ONE

What is language?

This chapter attempts to answer the general question: “What is language?”. One of the most obvious remarks that can be made on human language is that it exists in the form of a variety of different languages. At present, more than 6000 spoken languages are used in the world and the features they bear in common are referred to as “language”. They all show two main characteristics: (1) They make use of the vocal-auditory channel (to produce and perceive sounds), and (2) they are organized according to the principle of double articulation or duality of patterning: that implies a level of words, which bear meaning, and a level of sounds (phonemes), which are limited in number. Phonemes combine to form all the words of a given language. Language is the subject matter of linguistics, a relatively recent discipline comprising several branches, among which phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics are the ones most studied.

One of the first and most obvious remarks made by those approaching the study of human verbal communication is that language does not exist per se but in the form of several different languages. At present, there are more than 6000 spoken languages all over the world, each one representing a specimen of that typically human phenomenon called “language”. There is no evidence of human groups who do not speak at least one language. Generally, children can learn any language in infancy, unless they have Phoniatric or neurological impairments or learning disabilities. Stress is to be laid on the difference between language and communication (Hinde, 1972; Miller, 1951, 1981). To this effect, linguists have defined language as a verbal communication tool based on double articulation.

Two main features differentiate a human spoken language from any other form of communication: the use of the vocal-auditory channel and the principle of double articulation. All spoken languages use the vocal-auditory channel: they are spoken and can be understood because speakers produce particular sounds that are perceived and comprehended by listeners. A language also utilizes other communication modalities, such as writing and fingerspelling, but they derive from the spoken language. In addition, languages are always organized according to the principle of double articulation, that is, at two levels. The first level—also called first articulation—refers to words, i.e. the smallest units of meaning, that can combine to form an almost infinite number of sentences. The second level, or second articulation, refers to sounds peculiar to a given language. They are limited in number and meaningless. They are called phonemes and can combine to form all the words of a given language. This duality in the structure of any language allows the speaker to produce an infinite number of sentences, utterances, and texts by using a relatively small and fixed number of sounds and words.

In deaf communities sign languages are used; these languages have many structural features in common with spoken languages, but they do not use the vocal-auditory channel. In addition, the great majority of signers acquire and use in their everyday life both the minority language (sign language) and the majority language (Woll & Kyle, 1994).

LINGUISTICS AND THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE

Linguistics is the science that studies language. It is generally subdivided into four main branches (Akmajian, Demers, & Harnish, 1979; Asher, 1994; Fromkin & Rodman, 1993):

1. Phonology studies phonemes, i.e. the sounds peculiar to every single language, and also deals with sounds as acoustic phenomena; it is thus sometimes further defined as “phonetics”. For example, /f/ and /v/ are two phonemes of the English language because they mark the only difference between the two words “fine” and “vine”. Although the letters of the alphabet have been invented as a way to represent phonemes graphically, they do not correspond on a one-to-one basis to the different phonemes of a language.

2. Syntax studies the rules governing the combination of words within sentences. For example, a syntactic rule of English is that the article must always precede the noun and not vice versa.

3. Morphology studies the rules governing the internal structure of words, i.e. rules of concordance between adjective and noun, or gender, or number, etc., as well as word inflection and derivation. The systematic addition of an “s” to form the third person singular of verbs in the present tense (e.g. “he works”) is an example of a morphological rule in English.

4. Semantics studies the relationship between words and their meaning. Words carry pieces of infomation, called semantic properties; some words may have more semantic properties in common than other words have (e.g. girl and woman as opposed to stone and apple).

Phonetics and phonology

When a linguist approaches a formally unknown language for the first time, his duty is to find out the precise number of phonemes of this language. This operation is called phonemic analysis and implies the detection and description of every single phoneme of a language. Linguists have developed a special method to transcribe these sounds objectively onto paper, namely the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which makes it possible to note down every phoneme of all languages that have been identified and formally studied so far. Phonemic analysis basically depends on the idea of word segmentation, which, in turn, derives from the invention of alphabetic writing.

A phoneme is the minimal sound distinguishing two words of a given language that would otherwise be identical. A phoneme is thus the smallest distinctive segment of sound between two similar sound sequences. For example, bat and pat are two different English words with different meaning and they only differ in the starting sound /b/ as opposed to /p/. Therefore. /p/ and /b/ are two separate phonemes in English. By similarly comparing and contrasting a large number of words in order to define “minimal pairs”—an operation that is called commutation test—a linguist is able to identify all the phonemes necessary and sufficient to describe the phonemic repertoire of a language. When carrying out a commutation test, a linguist substitutes one sound segment with another and asks a native speaker (an informant) if the substitution implies a change in meaning. The procedure continues until all phonemes of a language have been detected.

It is likely that the limited capacity of motor, perceptive, and mnestic skills in humans has implicitly set a limit on the number of possible phonemes of any given language. None of the languages that have been studied so far have more than 150 phonemes (70% of all languages spoken in the world have on average 20–37 phonemes). This may be due to the fact that the human brain cannot deal effectively with a larger number of separate sounds.

It should be noted, however, that the concept of the phoneme is an abstract entity and has been invented by modern linguistics. At the level of physics and acoustic engineering, researchers have not yet succeeded in identifying and strictly marking the physical boundaries of a consonantic phoneme within the context of a sound sequence forming a word. This is mainly due to the fact that, as experts in acoustics have found out, a given phoneme is never articulated in exactly the same manner either by one speaker as opposed to other speakers, or by one and the same speaker within different linguistic contexts (e.g. the phoneme /t/ in the words study and stool), or even by the same speaker within the same linguistic contexts but under different emotional circumstances.

The different forms of articulation of a phoneme are called allophones. Although they have slightly different acoustic properties, a listener perceives and classifies them as one and the same phoneme of a given language. As underlined by Malberg (1974), the phoneme is represented both in the brain of the speaker and the listener, whereas allophones are “formed” in the phonatory organs and are found in the sound waves. When listeners want to decode a vocal message, it is in the sound waves that they find the implementation of the same phonemes the speakers intended to produce when they planned their messages. If listeners do not make this kind of phonemic identification, they will not be able to interpret the message correctly. Therefore, when an Italian monolingual listens to the English word black [blæk], he will probably have the impression of having heard [blek] or [blak], because the phoneme /æ/ does not exist in Italian. He will thus classify the English phoneme /æ/ as an allophone of the Italian /e/ or /a/.

After proposing the concept of phoneme, linguists found that phonemes had to be broken down further into smaller units if they were to be described in detail. These smaller units are called distinctive features, each of them corresponding to the smallest difference existing between two different phonemes. A phoneme is thus made of several concurrent distinctive features—partly shared by other phonemes, yet never exactly the same in two separate phonemes. Some linguists chose to describe phonemes according to their acoustical properties, others still according to the way they are articulated. Both types of classification use distinctive features, and both present pros and cons. I personally believe that the classification based on articulation is simpler and, at the same time, more useful for the purpose of describing specific language disorders. By definition, according to the principle of the so-called dual opposition, a distinctive articulatory feature may be present or absent in a given phoneme. Distinctive features are abstract entities which provide a description of a series of muscle movements the speaker has to perform in order to shape his vocal tract (i.e. the system producing the sounds of language) into a given configuration.

A list of the main distinctive features used to describe the phonemes of most Indo-European languages follows. These features apply to languages like Italian, English, French, Spanish, etc.

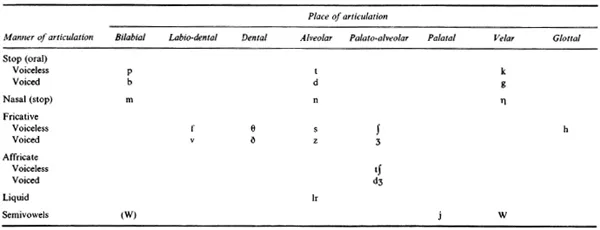

Consonants may be classified according to place and manner of articulation on the basis of the following distinctive features (see Table 1.1):

1. Voiced consonants: If a linguistic sound to be produced requires the vibration of the vocal folds, this sound is called “voiced”, otherwise it is “voiceless”. In the latter case, the vocal folds remain open as in normal breathing. Voiced consonants comprise: b, d, g, v, z, m, n, and 1. Vowels are all voiced sounds.

2. Plosives (stops) are the simplest to be produced and the clearest in perception. During phonation of a plosive, air is temporarily blocked in some parts of the vocal tract, e.g. by the lips (b, p), near the teeth (d, t), or in the region of the soft palate (velum) (/k/ as in “cat”, /g/, as in “gap”). In this case, some linguists make a further distinction between labial, alveolar, and velar consonants, respectively.

3. Fricatives, also called constrictive consonants, are characterized by a narrowing of some parts of the vocal tract; air escapes through a small passage, e.g. between the lips and the teeth (labio-dental consonants /v/, as “vat”, and /f/, as “fat”), between the teeth (interdental consonants /θ/, as “thin”; /đ/, as “then”), in the alveolar region (/z/, /s/), in the larynx (/h/, as in “hat”), or in the palato-alveolar region (/∫/, as in “fish”; /3/, as in “azure”). This narrowing creates friction and attrition between air and some anatomical structures of the phonatory organs, thus making the hissing sound typical of this group of consonants.

4. In affricates, the effect of an occlusion is followed by that of a friction, e.g. /t∫/ as in “rich”, or /d3/ as in “judge”. They are produced at palato-alveolar level.

5. Nasals are produced when air flows through the nasal passages because the soft palate is raised in the upper position; at the same time, there is an occlusion either of the lips (/m/, as in “smack”), or in the alveolar region (/n/, as in “nick”), or in the palate (/η/, as in “sing”).

6. Liquid consonants imply a partial narrowing of the vocal tract so that the air flow is not completely blocked. Examples of liquid consonants are /l/, as in “call” and /r/, as in “singer”.

Vowels are classified according to the position of the tongue within the oral cavity: anterior versus posterior, high versus low, central, etc. For example, /a:/ is a central low vowel, /u:/ is a posterior high vowel, etc.

The analysis and description of the phonemes and their distinctive features belong to a specific branch of theoretical and applied linguistics. However, the use of modern computerized devices and of automatic speech recognition techniques has highlighted that all the classification methods proposed by phonologists and phoneticians only partially reflect the real sound production process. It is hoped that in the near future computers will perceive and understand these sounds and thus contribute to the “translation” of oral language into written language.

TABLE 1.1

Classification of English consonant phonemes according to their place and manner of articulation (adapted from Aitchison, 1992).

One of the major difficulties researchers working on automatic speech recognition are still facing is the fact that all the sounds forming the words of an oral message are linked together in an uninterrupted sequence. The monitoring—by means of special cameras (cineradiographs)—of the articulatory movements performed by a speaker during the production of words has shown that the various phonemes cannot be separated. It has also shown that some phonemes are produced concurrently and consequently, which is due to the fact that the supralaryngeal vocal tract can be engaged in the coarticulation of several phonemes at the same time (Perkell, 1969).

Syntax

The word syntax derives from the Greek syntaxis, literally meaning “combination” or “putting together”. It traditionally refers to that branch of linguistics that deals with the way in which words are linked together in order to construct sentences that convey intentional meanings. One of the major goals of syntax is to identify constant, i.e. “universal”, grammatical rules applicable to all languages in the world. One of the main debated issues in the field concerns the segmentation of the minimal units of discourse. As early as in the second half of the 19th century, the English neurologist John Hughlings Jackson, on the basis of his clinical findings, suggested that the smallest linguistic unit was the sentence. In his opinion, to talk means to produce sentences, in his words “to propositionize” (Jackson, 1874/1958). At present, several linguists agree on the idea that the sentence is indeed a constant feature of the syntax of all known languages. North-American linguist Philip Lieberman proposed a biological explanation for the presence of the “sentence” unit in all languages. He claims that the slight lowering of the voice pitch caused by the natural exhaustion of expiratory air during phonation is perceived by listeners as a sign that the sentence is coming to a close. At the end of a sentence, speakers have no air left in their lungs, thus they have to pause briefly and breathe in again before uttering a new sentence (Lieberman, 1967, 1975). However, it must be noted that individuals can produce sentences of indefinite length, independently of the amount of air flow through their lungs. In addition, the sentence is an abstract grammatical concept based on a linguistic theory.

The identification of constant syntactic rules across languages turned out to be difficult. North-American linguist Edward Sapir highlighted the numerous differences in the syntactic organization of the various languages. Sapir classified languages on the basis of their main syntactic features and distinguished analytical languages, i.e. with a fixed and precise word order within the sentence, from synthetic languages, i.e. the word order is less fixed. Consider the following four Latin sentences: “Hominem femina videt”; “Femina hominem videt”; “Hominem videt femina”; “Videt femina hominem”. They all mean “The woman sees the man” with slightly rhetorical and stylistic differences. As word order in Latin does not affect meaning, it follows that Latin is a synthetic language. In contrast, English is an analytical language, because a change in the word order implies a change in meaning. Consider the following sentences: “The man ate the chicken” and “The chicken ate the man”. Th...