This is a test

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book addresses issues of space, historicity, architecture and textuality by focusing on Singapore's singular position in the region and as a global city. The articles consider how various experiences of Singapore, both from within and from outside, help to complicate existing assumptions about global urbanism, postcolonialism, and architectural theory while producing challenging new ideas from a variety of disciplines concerned with how space, historicity, architecture and textuality inform one another.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Beyond Description by Ryan Bishop,John Phillips,Wei-Wei Yeo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: Beyond Description: Singapore Space Historicity

Ryan Bishop, John Phillips, and Wei-Wei Yeo

BEYOND DESCRIPTION

This volume contains a collection of articles that productively interpret the architectural spaces of Singapore, while addressing issues of space, historicity, architecture, and textuality. The main underlying assumption is as follows: any site of the architectural is always going to be more than its mere material presence. Accordingly, the articles consider the ways in which the architectural comes to have specific meanings, and must thus go beyond descriptions of its empirical forms. The key intersection would be between space and history. However, while intersections like this cannot be located through empirical study, we do not accept that independent existing theories can be simply applied to the spaces we wish to deal with. If our accounts of Singapore are to be produced through analysis and interpretation we must more than ever think hard about the problems and possibilities of interpretation.

The collection does not attempt to put into practice claims for alternative epistemological frames. A number of interesting recent studies do attempt to bring alternative ways of conceptualizing urban space to contemporary non-Western urban sites. Ackbar Abbas, in his Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance (1997), makes the following observation about present-day Hong Kong: “the apparently permanent-like buildings and even whole towns – can be temporary, while the temporary-like abode in Hong Kong – could be very permanent” (9).1 Abbas argues that a phenomenon of this kind (which is as relevant for Singapore as it is for Hong Kong) requires “something more” than the so called “cult of the ephemeral” derived from Louis Aragon’s novel Paris Peasant and established as a key reference for urban studies by Walter Benjamin. Abbas engages a number of key contemporary theoretical models, those variously of Paul Virilio, Henri Lefebvre, Jean Baudrillard, Jean-Francois Lyotard, and Deleuze and Guattari in order to explain the phenomenon of disappearance and its relations to what he identifies as “the ephemeral, to speed and to abstraction” (8), as it pertains to Hong Kong. This allows him to read and interpret a range of Hong Kong cultural productions (cinema, writing, buildings, photography) through a lens constructed from a variety of contemporary theoretical views and subtly refocused through postcolonialism. While effective on its own terms, and justly admired, Abbas’s method changes very little either in terms of academic practice or how we understand environments. Despite the subtlety and critical force of the arguments themselves, which address the conditions of Western thought at their most basic, their application simply repeats the maintenance of the subject of science and the dream of objectivity, which is its counterpart. Furthermore, the strategies Abbas deploys are applied to a range of cultural products that are read for what they have to say about the built environment, which allows him to ignore the difficulties of what we would argue is the inevitable mediation that conditions all experience.

Our own claim would be, first, that urban space and architecture are at their deepest level of significance always beyond description and, therefore, beyond any epistemological frame whatever. So our alternative is not another epistemological frame. It is an alternative to epistemological frames. Second, it follows that knowledge of urban space can only be accessed by engaging with particular architectures and spaces. Accordingly our focus is Singapore. We believe we have achieved two things in this respect. First, we have been able to access aspects of Singapore that add up to a significant contribution to our knowledge and understanding of the city-state in its historical and global relations. Second, we have been able to establish aspects of Singapore that are significant when compared with often vastly different situations that govern other global cities.

We do not accept that sites like Singapore simply exemplify any theory, however it has been constructed. Nor do we believe that theory can be rigorously separated out from or simply applied to empirical spaces or vice versa. Problems emerge whenever this is attempted. We would argue that both urban theory and urban space are subject to very similar constraints at the level of their conditions of possibility. The problem resides most clearly in the ways that Singapore tends to describe itself. As an exemplar of a certain kind of technological rationality, Singapore produces its self-identifications in ways that often conflict with its actual conditions. The collection, therefore, focuses on the relationships and disjunctions between conditions and descriptions, which all dichotomies between theories and actual spaces repeat.

Singapore has a singular position regionally and globally in relation to these concerns insofar as its history involves extended, strategic engagement with the twin enterprises of postcolonialism and globalization, as well as with colonialism. This history is readable in the city-state’s architecture and physical environment. The entire Marina Bay area, in fact, materially realizes this history. This area is both the old British colonial center of the city as well as the present commercial and government center. From the renovated luxury hotel the Fullerton, once a fort overlooking the confluence of the Singapore River and the strategic bay, to a host of other “colonial” buildings, Singapore flaunts its colonial past and postcolonial/global present through the historical maintenance of these buildings’ façades. The act of renovation preserves the colonial shell of the building while reworking the buildings from the foundation up to better suit contemporary use, whether as luxury hotel, bank, government building, or restaurant. Readable in the buildings, then, is a continuation, perpetuation, and multiplication of colonial richness into the present global order, while also using the striking juxtaposition of colonial buildings and modernist high-rise buildings to reveal a specific continuum and continuity.

The visually jarring but aesthetically attractive connection of the colonial and modernist architecture is also deployed as a mode of attracting global capital to Singapore, a means of demarcating Singapore as both different from other global capitals and a repetition of them. The difference found in the colonial buildings reveals a history and historicity not always so blatantly displayed, often explicitly overturned or rejected, in other postcolonial cities while also marking it as different from the monotonous homogeneity of modernist skyscrapers that dominate financial centers of other global urban sites. The converted shop houses on Boat Quay, now housing upscale restaurants and bars that serve the employees of the banking high-rises towering above the upgraded yet historically maintained buildings, offer transnational corporations a different kind of physical locale for setting up shop, but one that is not too different. And in the continuation and intensification of global capital speculation running from colonialism to the present, Singapore’s built environment provides a historicity that tells us a great deal about the various phases of the continuum.

Figure 1.1 The Padang and the Singapore Cricket Club (foreground); skyscrapers of the central commercial district (background)

This volume, then, considers how various experiences of Singapore, both from within and from outside, help to complicate assumptions about global urbanism, postcolonialism, and architectural theory while producing challenging new ideas from a variety of disciplines concerned with how space, historicity, architecture, and textuality inform one another. Singapore, then, emerges as an exemplar of postcolonialism and global urbanism – or more broadly historicity, space, and architecture – that allows us to read other global cities in light of it while simultaneously allowing us to read other global cities in substantially different ways.

HISTORICITY

The question of Singapore’s historicity emerges forcefully with recognition of the country’s singular history of self-wonder and affirmation through constant, though varied, moves of self-description. Such moves are a staple of communication from official quarters such as ministerial speeches and government directives, and they are delivered with a certain rhetoric that is underpinned by a belief in and urgency about the need for agile and incessant transformation. In critical explorations of Singaporean culture and history, frequently linked to the question of national identity, the trend of self-description is similarly prevalent. Critique by description regularly re-visits areas such as postcolonialism, ideologies of national survival and economic success, the influence of global popular culture, and multi-racial sensitivities. Such moves demand analysis. We may assume that any system, ensemble, institution – anything, that is, which brings its elements together under a principle or set of principles – has come about on the basis of certain historical and systemic conditions. And no such ensemble would fail to produce moments when its relationship to those conditions are thematized, dramatized, or otherwise represented.

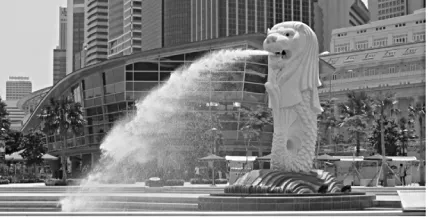

These moments of self-identification produce récits, including myths and fictions, as factual narratives. Such representations can always be compared with the historical and systemic conditions themselves, which are also readable at the level of an ensemble’s performance. Take the Singapore Merlion for instance. The Merlion, a logo found on government stationery up to the late 1990s and a subject of address for many Singaporean poets, is a mythical creature – one invented by the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board in 1977. Created to lend mystique to the island’s history, the Merlion has become the site of other narratives. Poets from the first generation to the present day have written about the Merlion in earnest eulogies, and more recently, with wit and irony. For many locals it is a symbol of geomantic significance. When the Merlion was recently moved from its former home at the mouth of the Singapore river, where it had become obstructed by Esplanade bridge, to a more prominent position facing Marina Bay and the newly opened Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay arts center, this was widely interpreted as a move to arrest the city-state’s economic slowdown and perhaps also to signal a new start as it embarks on a new phase of economic restructuring. The Merlion began as a pragmatic gesture from which separate lines of significance have been drawn. Its symbolism for Singapore is not easy to place, just as the very perpetuation of its aura is perplexing. The example of the Merlion shows that it is imperative for our principle of interpretation to be located in the space, the disjuncture, or gap between the statement about and the performance of the relation between the ensemble and the conditions of its own existence.

This volume is therefore concerned with excavating the spaces between the descriptive frameworks and the complex legacy of Singapore’s postcolonial and global urban space. As soon as we begin to talk of spaces between, it becomes clear that we are no longer simply addressing space in its empirical, observable sense. Observable space would be measurable. Spaces can be described and evaluated, as Bob Powell does in his article on South Bridge Road, when he describes the bridge as “a modest structure by today’s engineering standards but perfectly serviceable with high arches and slender suspension columns to support the carriageway.” This ability to describe, evaluate, and account for the spaces of the city constitutes a key component of urban analysis. However, the many uses of the term space that we would normally regard as figurative also play an indispensable role. For instance, in analogy with the literal bridge, we talk of bridging the space between buildings and their history, and, as we have just done, the gap between the ensemble and the conditions of its existence. This figurability allows us to speak of all kinds of phenomena, which are not strictly spatial, in spatial terms. Conventionally we would suppose that the literal logically precedes the figurative, and that these figurative uses are thus derived from the literal. However, the difference between these two ways of talking about space presupposes a way of conceptualizing space that is neither literal nor figurative but which allows our use of both literal and figurative senses.

Figure 1.2 The Merlion – a fanciful blending of fish tail and lion head

For instance, the Ancient Greek term topos reveals how both the literal and the figurative senses of space emerge from a prior form of conceptualization, what Immanuel Kant calls the transcendental imagination. Topos gives us the following familiar terms: topic, topography, and topology. The first addresses a space of thought, while the second denotes how we map spaces. The third bridges the two by allowing a flexible or conceptual mapping, which is neither literal nor figurative. This is why – even when we are describing space – our topic will always be in some sense beyond description.

SPACE

Not only does space have unavoidable conceptual dimensions to it but, taking our argument about beyond description a step further, we can also now say that thought itself seems impossible outside its own architectural constraints. The disciplinary division of the institutions of knowledge demonstrates this concretely. So, on the one hand, the possible coherence of any theoretical reflection on urban space seems seriously threatened. If, as modern philosophy teaches, our perceptions are structured spatially a priori, then all attempts to treat urban space objectively must fail. On the other hand, however, if we accept the continuity of structural constraints on both environmental and theoretical boundaries, a number of productive possibilities emerge as the space of theory overlaps in curious and productive ways with urban space, each providing means for considering the other. Neither domain can ever contain the other despite attempts to erect barriers and borders demarcating them. Where this containment does not hold is the topos (physical and intellectual) from which the articles in this volume emerge.

Architecture does not simply enclose but rather it produces space. The question of architectural constraints and enclosures forces the space of thinking to interact with the space of dwelling. In the context of contemporary global urbanism the space of thinking is not separable from the technologies of speed, including information technologies and telecommunications. Speed in the current moment firmly places space and architecture within geopolitical concerns, especially when one considers the deeply intertwined development and application of virtual reality modeling for military and architectural purposes, as evidenced at MIT and the Media Lab founded there by Nicholas Negroponte. The profound relations that converge in space and time interacting with speed in contemporary urban sites demand closer scrutiny.

As Paul Virilio has discussed, speed affects spatial domains as well as temporal ones, having significant effects on architecture itself. The life span of buildings is increasingly being delimited, with cities such as New York and Paris requiring building contractors to obtain demolition permits at the same time as they apply for construction permits. The emphemeralization of commodities essential to contemporary global consumer markets has its analogue in the emphemeralization of labor and buildings. Demands for increased speed and foreshortened building lifespans have profound ramifications for the interactions between architectural practices and theory and urbanization processes. One area that demands further study involves the conceptualization of vertical and horizontal space, and how buildings and sites manifest different types of temporality. Further, these demands fundamentally alter the means by which so called historical districts, historical buildings, and older neighborhoods are understood, defined, and delineated, especially with regard to “use.” In Singapore, more often than not, conservation planning seems to begin and end with the question of the economic value or opportunity cost of an area or a building. Technologies of speed in these cases are reproduced and developed as part of a general discourse of efficiency and productivity, such that the technologies responsible for producing or transforming the situations tend to be described in terms of the improvements they bring to them. A characteristic of this discourse is that it submerges positions and facts that might contradict its sense of benign progress. This is, once again, why it is necessary to go beyond the empirical and the merely describable aspects of the urban environment.

Once we focus on aspects that cannot be considered empirically, a relation between the built environment and what we would call the un-built emerges. Much as the literal and figurative conceptualizations of space reveal a prior condition that makes them possible, the built environment similarly reveals an inescapable connection with its un-built. The built, of course, designates both the concrete structure and the various manifestations of its conception: plans, models, and blueprints. But for the design to have been possible one must consider the undetermined and thus un-conceptualized possibilities against which a design decision is always made. In this exact sense the un-built corresponds to that notion of space that constitutes the condition of possibility for both literal and figurative conceptions and experiences of it.

The point here is to grasp that the un-built plays an intrinsic and essential role for the built environment. The un-built helps us understand what is beyond description in any urban space. Several dimensions are implied beyond the standard three dimensions normally attributed to built space. It is a matter of thinking through the built not only in terms of the concrete decision that it represents, but also in terms of its occupation of the imagination, at the basic level of the image. For instance, the Eiffel Tower in Paris from the outset operates as a repeatable image that is both independent of its original purpose and liable to all kinds of possible appropriation. In this case the tower becomes the imaginal logo of Paris itself. With the invention of the Merlion in Singapore we witness an attempt to appropriate the effects of a process that has become iconic of the global city generally.

More forcefully perhaps the un-built allows a building to operate as the focus for a field of contexts, and thus to re-contextualize its own environment. In this way Singapore’s “Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay” re-contextualizes the Marina Bay area as the hub of global culture as well as capital. Furthermore, the un-built has apparently interrelated temporal dimensions: the past un-built (demolished, transformed, historicized) allows the new to be buil...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- BEYOND DESCRIPTION

- THE ARCHITEXT SERIES

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CHAPTER 1: BEYOND DESCRIPTION: SINGAPORE SPACE HISTORICITY

- CHAPTER 2: OF TREES AND THE HEARTLAND: SINGAPORE’S NARRATIVES

- CHAPTER 3: TOWARD A SPATIAL HISTORY OF EMERGENCY: NOTES FROM SINGAPORE

- CHAPTER 4: ”THE VERTICAL ORDER HAS COME TO AN END”: THE INSIGNIA OF THE MILITARY C3I AND URBANISM IN GLOBAL NETWORKS

- CHAPTER 5: AT HOME IN THE WORLDS: COMMUNITY AND CONSUMPTION IN URBAN SINGAPORE

- CHAPTER 6: EVANGELICAL ECONOMIES AND ABJECTED SPACES: CULTURAL TERRITORIALISATION IN SINGAPORE

- CHAPTER 7: SINGAPORE: A SKYLINE OF PRAGMATISM

- CHAPTER 8: THE AXIS OF SINGAPORE: SOUTH BRIDGE ROAD

- CHAPTER 9: MODERNIST URBANISM AND ITS REVITALIZATION

- CHAPTER 10: POST-FUNCTIONALIST URBANISM, THE POSTMODERN AND SINGAPORE

- CHAPTER 11: THE TROPICAL CITY: SLIPPAGES IN THE MIDST OF IDEOLOGICAL CONSTRUCTION

- CHAPTER 12: INTELLIGENT ISLAND, BAROQUE ECOLOGY

- CHAPTER 13: AS THE WIND BLOWS AND DEW CAME DOWN: GHOST STORIES AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY IN SINGAPORE

- CHAPTER 14: URBAN NEW ARCHIVING