![]()

Part I

THE LIFE OF COLLECTIVE MEMORIES

![]()

Chapter 1

On the Creation and Maintenance of Collective Memories: History as Social Psychology

James W. Pennebaker

Southern Methodist University

Becky L. Banasik

University of Chicago

In 1973, Kenneth Gergen ushered the deconstruction movement into social psychology by arguing that the theories and findings within social psychology were dependent to a large degree on the prevailing culture. Further, because the field was generating culture- and time-dependent scientific results, these findings should be considered as historical data points or records. Social psychology, in his view, was a form of history. At the time, Gergen implied that history itself was an impartial truth with social psychological findings serving as archival reminders of the ways people thought and behaved at the time the studies were conducted. Although this chapter agrees with many of Gergen’s assumptions, it is important to appreciate that history itself is highly contextual. Indeed, social psychological processes help to define history. The ways people talk and think about recent and distant events is determined by current needs and desires (see also Tetlock, Peterson, McGuire, Chang, & Feld, 1992). Just as the key to the future is the past, the key to the past is the present.

In the United States over the last half century, most adults would agree that a relatively small number of national events have profoundly affected Americans’ collective memories: World War II, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the peace movement/anti-Vietnam/Woodstock period, Watergate, and, perhaps, the explosion of the Challenger space craft. This is not to say that other extremely important events did not occur—such as the Korean War, the Bay of Pigs in Cuba, the election of Ronald Reagan, and the Persian Gulf War. However, this second group simply did not have the same psychological impact as the first. Why does society tend to spontaneously recall the first set of events rather than the second? What distinguishes an event that yields a broad-based collective memory from one that does not? By the same token, in whom are these collective memories instilled and what maintains them over time?

The creation and maintenance of a collective or historical memory is a dynamic social and psychological process. It involves the ongoing talking and thinking about the event by the affected members of the society or culture. This interaction process is critical to the organization and assimilation of the event in the form of a collective narrative.

ELEMENTS OF COLLECTIVE MEMORY

The recent resurgence of the term collective memory can be traced back to the French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (1992) and the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky. Each questioned the assumption that memory resides in the individual. Halbwachs addressed the topic of collective memory, and Vygotsky presented a theory of the mind allowing others to theorize about it (Wertsch, 1985). Halbwachs asserted that all memories were formed and organized within a collective context. Virtually all events, experiences, and perceptions were shaped by individuals’ interactions with others. Society, then, provided the framework for beliefs and behaviors and recollections of them. Vygotsky’s assumptions were similar in noting that adult memory is dependent on society or community. The social mechanism guiding memories was language—the primary symbol system that defines the framework for individuals’ memories (Bakhurst, 1990). By extension, people’s ways of remembering the past should be dependent on their relationship to their community (Radley, 1990).

In stark contrast to the assumptions of collective memory, most traditional laboratory-based memory research has attempted to understand memory as a context-free, isolated psychological process. This laboratory-based strategy has yielded some important findings about what individuals can and do remember. For example, memories for events, objects, or facts (declarative memory) are most likely to be remembered if they are unique, provoke emotional reactions, are actively rehearsed, and are associated with subsequent changes in behaviors or beliefs (e.g., Craik & Lockhart, 1986). It is particularly important to appreciate that unique emotion-provoking events requiring no psychological adaptation are not necessarily memorable. Moreover, while individuals are psychologically adapting, they may be more likely to remember events that occur during that time (Pillemer, Rhinehart, & White, 1986).

One interesting subset of memories is the phenomenon of flashbulb memories (Brown & Kulik, 1977). Flashbulb memories are an example of a mixture of personal circumstances and historical events in memory. When people hear the news about a shocking significant event, like the fall of the Berlin Wall, they not only remember details about the event, but also their personal circumstances when they heard about it. Therefore, almost everyone who was at least 12 years old at the time of the tearing down of the Wall can tell their story (their narrative) of what they were doing when they heard the news.

Strangely enough, these flashbulb memories, which are reported with confidence, are often inaccurate (e.g., Bohannon & Symons, 1992). This is understandable because all memories fade or are reconstructed. Neisser (1982) hypothesized that flashbulb memories are not established at the moment of the event, but after the event when the significance of the event to society or to the individual has been established, leaving more room for error. People have such a vivid, long-lasting recollection when it comes to flashbulb memories because they allow individuals to place themselves in the historical context, and when relaying their personal flashbulb memories to others, they are able to include themselves in the event.

These event features that are important for individual memories should, by definition, be necessary for collective memories as well. Specifically, a society should embrace and/or collectively remember those national or universal events that affected their lives the most. Interestingly, this suggests that massive national situations that ultimately did not affect the course of history should not be part of the national psyche to the same degree as events that signaled important institutional or historical changes.

Consider, for example, the four most recent wars fought by the United States: World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Persian Gulf War. Each provoked tremendous national discussions, and was associated with the loss of life and huge consumption of resources. Only two, however, appear to have had any long-term psychological consequences: World War II and Vietnam. Surprisingly, winning versus losing does not appear to affect collective memory. Rather, these two wars were important turning points for American self-views. With World War II, the United States emerged as a dominant military and economic force for much of the world. Vietnam changed this egocentric perspective, thereby producing a new generation who questioned the role of the United States in the world.

A critical initial step in understanding both individual and collective memories, then, is that the long-term impact of events themselves help to determine the memories. Studies on individual memories, for example, demonstrate that people tend not to recall common events or objects that have no personal impact or adaptive importance (e.g., Bruce, 1985). By the same token, a war may give the impression of changing the course of history at the time. However, if no institutional and/or personal effects are apparent once the war is over, there will be very few collective memories. Citing the powerful social memory of the execution of Louis XVI in France in 1793, Connerton (1990) demonstrated that previous murders of French kings were ultimately unimportant because the basic dynastic succession remained. With the French revolution and the death of Louis XVI, however, the basic structure of government changed forever.

RESHAPING COLLECTIVE MEMORIES FOR THE PRESENT

Significant historical events form stronger collective memories, and present circumstances affect what events are remembered as significant. Fentriss and Wickham (1992) argued that memory plays an important social role. In their view, individuals invent or redefine the past to fit the present. Evidence that current events affect the ways a society remembers them can be seen in the commemorative symbols the society constructs (e.g., Connerton, 1990; Schwartz, 1991).

Schwartz (1982) documented the people and events commemorated in the paintings, statues, murals, frescoes, reliefs, and busts displayed in the U.S. Capitol. There are congressional procedures that commission artworks for the Capitol building that encourage diverse views of what should be commemorated. Schwartz noted that this effort to reflect the nation’s diversity did not result in an evenhanded display of the important events in American history. Instead, he found that certain historical periods were disproportionately represented and people or events that were not deemed important to the people living in the time period depicted were often “picked up” by later generations. For example, the early colonists commemorated John Cabot as a major explorer. But with the rise of anti-British sentiment came an interest in Columbus, who subsequently became the most celebrated explorer in the United States.

Schwartz (1991) also observed a similar phenomenon with regard to Abraham Lincoln’s reputation and how it changed after his death. Prior to his assassination, Lincoln was neither overwhelmingly popular nor a national hero. After his death, however, there was a 14–day funeral procession by rail passing through most of the largest cities in the country that was witnessed by millions of people. The combination of the funeral procession and the high emotions of the country surrounding the end of the Civil War started a trend in transforming Lincoln’s popularity that eventually elevated him to a status akin to George Washington. According to Schwartz, Lincoln’s image was further bolstered by a shifting national sentiment that believed in the common man rising to lead the people.

THE ROLE OF LANGUAGE IN AFFECTING COLLECTIVE MEMORIES

Translating events or images into language affects the ways they are thought about and recalled in multiple ways. Typically, if not always, language is a social act. When an event is discussed, its perception and understanding is likely to be affected by others in the conversation. On a more psychological level, talking about an event is a form of rehearsal. Further, the act of rehearsing the event through language can influence the way the event is organized in memory and, perhaps, recalled in the future.

Talking as a Memory Aid: Rehearsal

On an individual level, objects or events are most likely to be consolidated in memory if they are rehearsed (e.g., Baddeley, 1986). In laboratory settings, the most common ways by which events are rehearsed are that they are thought about in verbal form. Repeating a 9-digit number over and over again—either subvocally or out loud—helps the person to retain the number for seconds, minutes, or, on occasion, longer.

Most memories for events are quite different from phone numbers or lists of nonsense words in that they have a social component. As noted earlier, Halbwachs argued that virtually all memories are collective—in large part because they are discussed with others. Indeed, for societies to exist at all, the societal members must share a very high percentage of their experiences to increase the cohesiveness of their memories. Indeed, Shils (1981) claimed that for a society to exist over time, its communications must be said, said again, and reenacted repeatedly.

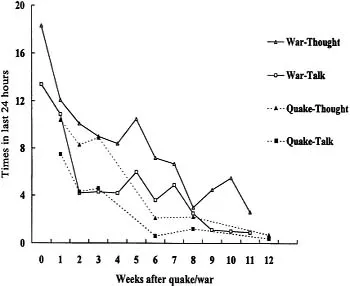

When a large-scale event affects an entire region or society, a common response is for people to openly talk about it. In two related studies on a natural disaster (the San Francisco Bay Area earthquake of 1989) and responses to the Persian Gulf War, the degree of self-reported talking and thinking about these events was startling (Pennebaker & Harber, 1993). In both of these studies, weekly or semiweekly samples of residents of San Francisco (for the earthquake project) and of Dallas, Texas (for the war project), were interviewed using random-digit dialing sampling methods immediately after the war or quake through at least 3 months later. Among the questions that both groups of samples were asked was “How many times in the last 24 hours have you talked with someone about the quake (or war)?” Similar questions asked the number on times subjects thought and heard about the quake or war.

As can be seen in Fig. 1.1, the degree of social sharing and ruminating about these events was remarkably high during the first 2 weeks following the quake and the onset of the war. Clearly, the raw ingredients for shared experiences and memories were being laid down. Not only were people discussing these events to a high degree, but they were bombarded with features of the events via the media. In other words, most residents received similar information from television and newspapers, which in turn was talked and thought about. Given these basic ingredients, it would be difficult for people not to have similar memories of the experience, that is, collective memories.

FIG. 1.1. Thoughts and conversations about war/quake.

Talking as a Forgetting Aid: Cognitive Organization

Just as talking about an event is a form of rehearsal that may aid memory, talking or translating an experience into language can help to organize and assimilate the event in people’s minds (cf. Horowitz, 1976). An emotional experience, by definition, provokes talking because those who are affected by it are attempting to understand and learn more about it (Rimé, 1995). Language, then, is the vehicle for important cognitive and learning processes following an emotional upheaval. Talking about an event may successfully organize and assimilate it, which will allow the person to move past the upheaval. Ironically, once an event is cognitively assimilated, individuals no longer need to ruminate about it and, once it is out of their minds, they may actually forget about it.

An intriguing example of how cultures forget important events can be seen in the case of the Persian Gulf War. As noted earlier, the degree to which people talked about the Persian Gulf War in the United States in the first weeks after its beginning was remarkable. Extrapolating from these numbers, it seems that Americans would have a clear memory for the major features of it. However, if talking about an event helps individuals to organize and forget about it, those who talked most about the war would be the ones with the poorest memories in the years following the war.

As a test of this theory, 76 university students who completed weekly questionnaires in classrooms about the degree to which they talked about the war during the time the war was ongoing were contacted 2½ years later (Crow & Pennebaker, 1996). In the 2½-year follow-up, the participants were asked a series of factual questions about the war, including: Who did we fight? [Iraq] Who was the leader of the opposing force? [Saddam Hussein] How many United States soldiers were killed? [148]. Astonishingly, most people’s memories for the war were extremely poor. It is interesting to note that two factors predicted poor long-term historical memory for the war: deg...