![]()

1

Egypt

I am one pure of mouth, pure of hands,

One to whom, "Welcome" is said by those who see him;

For I have heard the words spoken by the Donkey and the Cat,

In the house of Eternity.

(From the Book of the Dead)1

Egypt is the ultimate homeland of all domestic cats throughout the world, and so will always have a significant place in the history of the species. We are fortunate that a superb book has recently appeared on the topic, Jaromir Malek's The Cat in Ancient Egypt,2 that treats all aspects of the animal. A chapter devoted to Egyptian cats may therefore seem redundant; nevertheless, it is important for a work devoted to Greek and Roman cats to include a section on Egypt, since many later characteristics of the animal in iconography, symbolism, religion, and folklore have their origins in that culture. Furthermore, it remains true that important descriptions of the Egyptian cat come from Greek authors, most notably Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, and Claudius Aelian. Finally, we will emphasize the history of the animal in the later period of the country's history (1070 BC - 330 AD), not the earlier era.

The Libyan wildcat

The Felis sylvestris libyca, the direct ancestor of all domestic cats, is a feline opportunist that has not only survived but flourished in the drastically changing natural and human environments of North Africa for the last five million years. Its head and body length are some 30 inches (75 cm) and its tail, some 12 inches (30 cm). Its ears are not tufted as in other small African wildcats and it has proportionally longer legs than a domesticated individual. As in the case of F. sylvestris sylvestris, and indeed even more so here since the libyca is the direct ancestral form, there has probably been considerable interbreeding between it and the catus. This has led to a gradual reduction of its modern body size and other wild characteristics. This may be why an examination of many mummified ancient Egyptian cats shows that they are larger than the modern libyca (Fig. 0.2). The ancient cats were more closely related to the larger, ancestral libyca, and the modern libyca itself has declined in size through interbreeding.

Its color is also variable depending on genetics and local environments. Generally, however, the body is a "pale sandy fawn ... with a rufous line on the back and multiple traverse stripes of the same colour, though paler, on the body.3 The markings generally recall those of the common orange and grey striped tabbies. The tail is ringed and has a black, untufted tip, important features for the purposes of identifying it in works of art. Leopards (Panthera pardus), for example, have spotted tails and lions (Panthera leo) have plain tails with a tufted tip.

There are several significant Greek references to the libyca. Diodorus Siculus, who wrote a universal history that was published about 49 BC, noted that in a region of what is now central Libya, the wildcats (ailouroi) had driven out so many birds from the trees and ravines that none would nest there. This reference is made in the context of a military campaign undertaken by Archagathus, a general of Agathocles of Syracuse in 307 BC, against the Carthaginians. At this time, and indeed throughout the Roman era, North Africa still retained many forested regions.4

The natural historian Claudius Aelian, writing in the late second century AD, made many shrewd observations on cats and other animals in his De Natura Animalium. One passage on the taming of the Egyptian libyca deserves to be repeated in full:

In Egypt, the cats, the mongeese, the crocodiles, and even the hawks show that animal nature is not entirely intractable, but that when well treated they are good at remembering kindness. They are caught by pandering to their appetites, and when this has rendered them tame, they remain thereafter perfectly gentle. They would never set upon their benefactors once they have been freed from their genetic and natural temper. Man however, a creature endowed with reason, credited with understanding, gifted with a sense of honor, supposedly capable of blushing, can become the bitter enemy of a friend for some trifling and casual reason and blurt out confidences to betray the very man who trusted him5

That this animal was indeed a libyca and not a Felts chaus or margarita is indicated by the animals tamability, a characteristic generally absent from the two other species.

Aelian also notes the predation of wildcats on other animals and birds, and how these animals have evolved defensive measures to avoid it. In these instances, it is not certain whether the wildcats are the libyca, or another species; nevertheless, the interest in the stories lies in the preys' methods of escape.

A monkey, pursued by wildcats fled as fast as he could and climbed a tree. The wildcats also climbed the tree,

very swiftly, for they cling to the bark and can also climb trees. But as he was going to be caught, since he was one against many, he leapt from the trunk with his paws and seized the end of an overhanging branch high up and clung to it for a long time.6

The wildcats gave up the chase, descended the tree and went after other prey. This is also an interesting example of teamwork among wildcats in their hunting.

Aelian notes too that the Egyptian Goose is a fierce fighter and can defend itself from eagles, cats, and all other animals that come against it. Finally, there is the ibis, who also eats dangerous snakes and scorpions without harm to itself.

It makes its nest on the top of date-palms in order to escape the cats, for this animal cannot easily climb and crawl up a date-palm as it is constantly being impeded and thrown off by the protuberances on the stem.7

The miu: the domesticated cat

The earliest remains of cats in domestic contexts from Egypt date from about 4000 to 3000 BC, but are probably of tame wildcats rather than domesticated cats. Wildcats of various species were first represented in Egyptian art from about 1900 BC, about the time the libyca was domesticated. This is also the time that the first representations appear of what are probably domesticated cats. One bas relief from Coptos of about 1950 BC shows a cat sitting beneath a woman's chair, a common iconographic portrayal in later works of art. By 1450 BC, the cats are a common feature in Egyptian painting of domestic scenes.

For a few hundred years before this era, however, we find the first individuals named after the cat, as other individuals were named after other local animals such as "Monkey," "Wolf," and "Crocodile." The name given to the domestic cat by the Egyptians was the onomatopoeic "miu" or feminine "miit." So we find names such as Pa-miu, "The Tomcat," and Ta-miit, "The Cat."8

Among the factors that undermined the serenity and security of Nilotic life, the most significant were deadly snakes, such as cobras and vipers, and rodents, both mice and rats. Since there was little men could do to protect themselves from such dangers, the appearance of an animal that could destroy such vermin would have been a welcome event. Indeed, since snakes can inflict fatal bites on humans, it would have been literally a life-saving event.9 Since granaries and silos attracted rodents, they represented a reliable source of food for the cats, who would leave the grain alone. Feeding scraps to the cats would assure their presence near their food supplies and homes. As territorial creatures, they would soon strike up associations (if not exactly friendships) with the humans and come to regard the area around their homes as their own. Thus it was just as much a factor of the cats adopting the humans in their territory, as the humans adopting the cats.

Before long, the people began to recognize the benefits of having the cat in the house. Households with cats had more food, less sickness, and fewer deaths. Its personality and behavior compared well to the other pets they had in their homes, such as dogs and monkeys. Its cleanliness no doubt attracted the Egyptians, while its "house training" - the burial of its excrement outdoors in the sand, more preferable to the cat than the fertile earth of the fields — its killing of scorpions, rodents and snakes that may have entered the house, and its general rejection of grain-based food, the staple of the Egyptian diet as for most ancient Mediterranean peoples, must also have recommended it to their service. In exchange for comfort and safety, the cats were willing to give up some of their freedom. Selective breeding would ensure that only the tamest and best-behaved individuals would survive in human company.10

It must also be noted that the cat was a new type of domestic animal. Other animals were exploited for their hides, meat, milk, or hair. Some were used for transport, like the horse, donkey, mule, and later the camel. As we saw in the Introduction, the dog was used for hunting, herding, and for guard work but not for killing rats in antiquity. The cat, however, was used solely as a predator of small animals and later as a human companion.

Iconography

Cats occur frequently in the art of the New Kingdom (1570—1070 BC) and the Late Period (1070—332 BC). There are wonderful wall paintings of cats and, of course, some magnificent bronzes. Fortunately, these works have been beautifully illustrated and thoroughly described by Malek. Nevertheless, there are two major categories of images that are of interest to us because of their later use by both Greeks and Romans: the "cat under the chair," and the "cat in the marshes." In addition, there is an important series of bronzes depicting the cat goddess Bastet with her sistrum that will be treated in the sections on religion and folklore below.

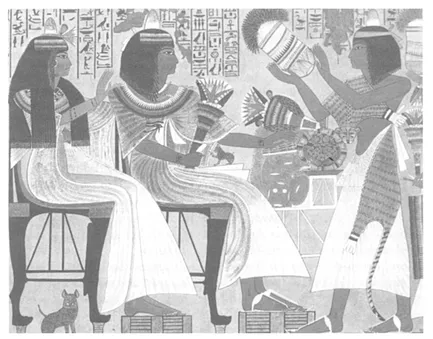

Most portrayals of the cat under the chair are in the context of a scene depicting a seated husband and wife accepting gifts and offerings from their servants or children. The cat invariably sits beneath the chair of the wife and sometimes a dog sits beneath the husband. For example, in Figure 1.1, we see the couple Ipuy and his wife Duammeres portrayed on their tomb, which dates to about 1250 BC. A cat sits beneath Duammeres' chair and a small kitten scratches at the garment worn by Ipuy. The cats themselves show the typical color and markings of the libyca, which has now been domesticated.

The cat under the woman's chair may symbolize her fertility and the association of both with the goddess Hathor. The dog or the monkey that is frequently found beneath the man's chair, although not on this particular scene, may symbolize his fertility as well.11 In these tomb paintings, the cat may symbolize the continual force of life even after death. In other scenes, the cats under the chairs play with monkeys, embrace geese, hiss at geese, eat food, or try to break free of their tethers, so they can eat some food that is placed nearby.12

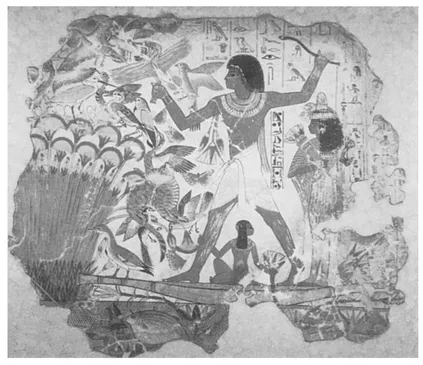

Another common theme is the cat hunting birds in the marshes. Often the cat is portrayed with a hunter on his boat or in the marshes attacking water birds. Figure 1.2 shows the family of Nebamun on a small skiff, while the family cat attacks the fowl. The painting is from Nebamun's tomb in the Theban necropolis and dates to about 1450 BC. It is one of the great masterpieces of Egyptian painting. Seldom in any artistic tradition are animals, plants, wildlife, fish, and people portrayed with greater empathy and realism. The cat is a masterpiece in itself and is shown assaulting three different birds at once! Nevertheless the animal is depicted with great naturalism, and is one of the best portrayals in existence. Once again, we see the beautiful golden-tan coat, the darker transverse stripes, and the ringed tail with the black tip (Fig. 1.3).

Figure 1.1 Ipuy, Duammeres, and their cats, tomb fresco, Deir el-Medina, 1250 BC

Figure 1.2 Nebanum and his family, tomb fresco, Theban necropolis, 1450 BC

The cat may indeed have been used to flush out the birds so they could be struck down by the hunter's throwing stick, spear or arrow. Alternatively, during the roosting season, the presence of a cat may force the birds to instinctively protect their nests so that the hunter can have several targets at once. On the other hand, it is more likely that Nebamun merely wanted to show his family together on their eternal journey, and naturally the family cat was included. The cat would do what came naturally when confronted by so many birds and, realistically, it would be quite difficult to train a cat to flush out waterfowl.13

The goddess in the house: the sacred cats of Egypt

Throughout history, many have believed that the cat embodies profound spiritual forces. This has been true not only among the ancient Egyptians and the Europeans, but also among the Asian Indians, Chinese, and the Japanese. Part of the reason for this may have been the remarkable sensory acuity of the animal. Its ability to predict the weat...