eBook - ePub

The Resurgence of East Asia

500, 150 and 50 Year Perspectives

This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Resurgence of East Asia

500, 150 and 50 Year Perspectives

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The East Asian expansion since the 1960s stands out as a global power shift with few historical precedents. The Resurgence of East Asia examines the rise of the region as one of the world's economic power centres from three temporal perspectives: 500 years, 150 years and 50 years, each denoting an epoch in regional and world history and providing a vantage point against which to assess contemporary developments.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Resurgence of East Asia by Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita, Mark Selden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia asiática. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Tribute and treaties

Maritime Asia and treaty port networks in the era of negotiation, 1800–1900

Takeshi Hamashita

States and the seas

Countries functioning as territorial states have long distinguished themselves from others by establishing boundaries, extending their territory even out to sea. The result has often been inter-state disputes such as clashes over 200-mile sea zones and conflicting claims to islands, as in the case of the Spratly Island issue with potentially large oil revenues at stake.1

The state has long claimed sovereignty, and in the days when all things were thought to belong ultimately to the state, negotiations and conflicts focused on exclusive possession of territory defined by formal boundaries.

The meaning of the seas cannot be fully appreciated as long as they are seen as opposed to the land and as long as one’s focus is on the land. The seas, in fact, form and set the conditions of the land. The seas and the land should be understood not as being separated by the coasts, but as part of a larger whole in which the land is part of the seas (and vice versa). The sea forms, in short, a road, a basis for communication and network flows, not a barrier.

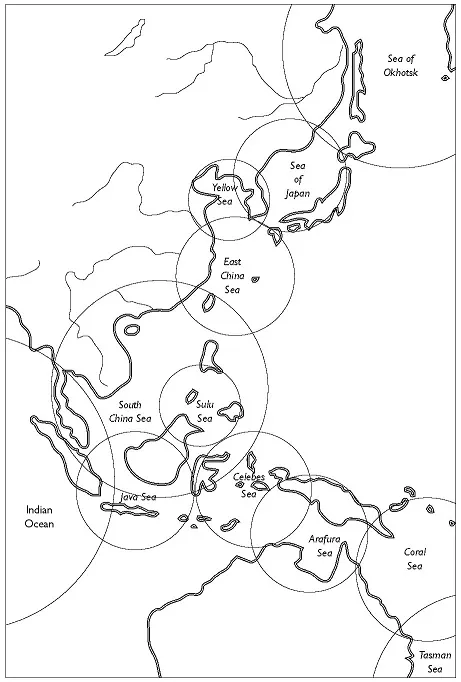

Looking at Asia from the viewpoint of the seas brings into focus the features that identify it as a maritime region par excellence. The seas along the eastern coast of the Eurasian continent form a gentle S curve extending from north to south (Figure 1.1). The chain formed by the seas that outline the continent, its peninsulas and adjacent islands, can be seen as shaping the premises of Asia’s geopolitical space. The “maritime areas” thus formed in and around Asian lands are smaller than an ocean and less closely associated with the land than are bays or inlets.

Let us follow the “Asian seas” from north to south. The Sea of Okhotsk shapes Kamchatka and Siberian Russia. Further south, it merges into the Sea of Japan; then comes the Bohai and the Yellow Sea. These, with the East China Sea, embrace the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese archipelago, and the islands of Okinawa. The chain of seas then divides in two. On the east is the Sulu Sea leading to the Banda, Arafura, Coral, and Tasman Seas. On the west is the Java Sea that stretches west and connects with the Strait of Malacca and thence to the Bay of Bengal. From the intersections of these seas, trade networks formed, pivoting on places like Nagasaki, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Malacca, and Singapore.

Figure 1.1 Maritime zones of Asia

Source: Takeshi Hamashita, China-Centered World Order in Modern Times (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1990). Used by permission of the publisher.

Asian studies in China, Japan and the West has, from its inception, revolved around the history of land-based states. However, to grasp the totality, particularly the regional integrity, it is necessary to study Asia in terms of the interfaces and exchanges that take place within and among maritime zones and that cross state boundaries.

The emergence of maritime zones

If the areas presently called East Asia and Southeast Asia are understood to be the maritime realm shaped and defined by the East China Sea and the South China Sea, the historical land–sea system of the region can be understood logically. The maritime world that functions here is not merely one of seas. Rather, it is composed of three elements. One is the coastal area where land and sea intersect. In the seventeenth century, the Kangxi emperor issued an order forcing the South China coastal population to move inland in an attempt to separate them from the influence of the powerful anti-Qing leader Zheng Cheng-gong (Koxinga) whose maritime empire extended from Fujian and Guangdong to Taiwan. This demonstrates the pivotal role of coastal areas in the maritime world.

Another important element is the sea-rim zone comprised of coastal areas. Along this rim are trading ports and cities that comprise the key nodes of the maritime area. These ports are not so much outlets to the sea for inland areas as points that connect one maritime zone to another. Historically, the merchants of Ningbo, located on the Chinese coast, for example, amassed wealth predominantly through coastal and maritime trade rather than from continental trade. Ningbo merchants played a particularly important role in trade with Nagasaki. Other maritime links that flourished in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries included Pusan–Nagasaki–Fukuoka trade linking Japan and Korea, the Ryukyu–Kagoshima route between the Ryukyus and Southwest Japan, Fuzhou–Keelung linking Southeast China and Taiwan, and Aceh–Malacca–Guangzhou linking the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, and Southeast China. Notably, the maritime concept has reappeared today in the concepts of the Japan Sea-rim and Yellow Sea-rim trade zones.

The third element of the maritime world is the port cities that link maritime regions through long-distance trade. Among cities of this type which flourished in the nineteenth century are Naha, Guangzhou, Macao, and Hong Kong. Okinawa’s Naha, for example, had long-established trade links with Fuzhou while Guangzhou’s links were with Nagasaki and Southeast Asia. Port cities linking the South China Sea and Indian Ocean included Malacca, and later Singapore and Aceh in Indonesia. In contrast to the land, the maritime world encompassed coastal trade, cross-sea trade, and chain-of-seas connections, for example, those linking the South China and East China seas. The result was an open, multi-cultural realm that was diverse and well integrated.

To understand the operational principles of the maritime world, it is necessary to examine the interplay of political, economic, and cultural factors that unfolded there.

The major historical principle that loosely unified the maritime world of East Asia was encapsulated in the tribute-trade relations, which functioned from the Tang through Qing dynasties, from the seventh century to 1911. This China-centered order nevertheless permitted Korea, Japan, and Vietnam to assert themselves as “centers” vis-à-vis smaller neighboring states under their sway. The region was sustained by a hierarchical order defined by the Confucian conception of a “rule of virtue.” Like any hegemonic order, it was backed by military force, but when the system functioned well, principles of reciprocity involving politics and economics permitted long periods of peaceful interaction.

In the China-centered order, tributary states sent periodic tribute missions to the Chinese capital, and each time rulers of tributary states changed, China dispatched an envoy to officially recognize the new ruler. In unsettled times, Chinese forces sometimes intervened to prop up or enshrine a ruler. Tribute relations were not only political but involved economic and trade relations as well. In exchange for the gifts carried to the Chinese court, tribute bearers received silk textiles and other goods from the emperor. Specially licensed traders accompanying the envoy engaged in commercial transactions at designated places in the capital. In addition, more than ten times as many merchants as these special traders exchanged commodities with local merchants at the country’s borders and at designated ports. In short, lucrative trade was the lubricant for the tributary system defining regional political, economic, and cultural intercourse. The sea routes and major ports of call of the tribute missions sent by Ryukyu to China, for example, were clearly established. Navigational charts were devised based on seasonal winds and on the points and lines established by surveying the coasts and observing the movements of the stars.

Not only overseas Chinese merchants based in East and Southeast Asia but Indian, Muslim, and European merchants participated in this tribute trade, linking land and maritime zones.2

A maritime zone, therefore, was also a tribute and trade zone. Moreover, such zones broadly defined flows of human migration. In Tokugawa Japan stories about castaways were often told to inspire fear, discouraging people from attempting to leave the land. In fact, however, when castaways were discovered, they were to be taken along the tribute route back to their home country at that country’s expense. Along the coast of Kyushu, private Chinese ships often took advantage of this rule, intentionally drifting up along the coast, and engaging in a brisk illegal trade before officials arrived to do their duty.3

Tribute trade and Ryukyu networks

To see what a trade zone was like, let us look at the Ryukyus.4 The Ryukyu Kingdom regularly sent missions to Southeast Asia to obtain the pepper and sappanwood it could not produce locally, and presented these to China as part of its tribute trade. The first volumes of the Lidai Baoan (Rekidai Hoan or Precious Records of the Ryukyu Kings), a collection of official Chinese tributary-trade records, states that during the Ming period (1368–1644), the Ryukyus engaged in commercial transactions with Southeast Asia, including Siam, Palembang, Java, Malacca, Sumatra, Annam, and Patani.5 It can be assumed that Japan, Korea, and China were among the trade partners in addition to these Southeast Asian countries. The Ryukyus, in short, was part of an extensive trade network. Stated differently, this far-flung Ryukyu network pivoted on but was by no means limited to the Ryukyu tribute trade with China.

The trade network had two distinctive features. One was that trade with Siam and other Southeast Asian countries was vigorous between the early fifteenth century and the mid-sixteenth century.6 The other was that, as far as we know from the Lidai Baoan, Ryukyuan trade with Southeast Asia declined while trade with Korea and Japan increased.

This phenomenon prompts us to ask two questions concerning the Ryukyus: what happened to the trade with Southeast Asia after the mid-sixteenth century? And what was the nature of the trade with Manila and Luzon in the context of Ryukyu trade with Southeast Asia?

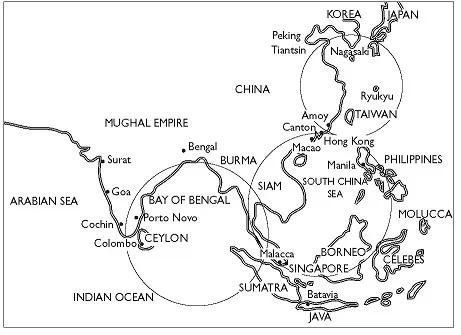

In examining these questions, we note that the Ryukyus were involved in two trade routes between the South China and Southeast Asia. One route ran along the island chains on the eastern side of the South China Sea from Luzon to Sulu and the other stretched along the coast of the continent on the western side of the South China Sea from Siam to Malacca (Figure 1.2).

The eastern route started from Quanzhou (or Fuzhou) in Southeast coastal China, and spanned the region between the Ryukyus, Taiwan, and Sulu. This route not only carried the trade with Southeast Asian tributary states but also, from the sixteenth and seventeen centuries onward, the trade with Spain centered at Manila – exchanging silk for silver – and with the Dutch East India Company centered on Taiwan. At the same time, the route ran farther north from Fuzhou where soybean and soybean meal arrived from North China in exchange for rice, sugar, porcelain, and silk. The western route, starting from Guangzhou, linked various parts of Southeast Asia following the coast to major Southeast Asian tributary states, including Siam, Malacca, and Sumatra. Rice, marine products, and spices were major items imported to Guangdong from Southeast Asia and then traveled inland to Guangxi, Hunan, and other parts of South and Central China. China’s exports to Southeast Asia were predominantly rice and sugar.

Figure 1.2 East and West maritime routes

Source: Takeshi Hamashita (1989: 249).

In 1666, ninety-six years after the records of official trade with Southeast Asia stopped appearing in 1570, the Ryukyu King Sho Shitsu asked that pepper, which was not produced locally, be excluded from the list of tribute goods. The Chinese court approved. This suggests that over the preceding century, using non-official trade channels, Ryukyu was able to obtain pepper from Southeast Asia for inclusion in its tributary shipments to China. Behind this development lay the increase in China’s rice trade with Siam, bringing more merchants from the Chinese coast to Southeast Asia. Ryukyuan traders were able to obtain pepper and sappanwood either by joining Chinese merchants trading in Southeast Asia or by direct purchase from them.7

Even after being invaded by the Satsuma domain of Tokugawa Japan in the early seventeenth century, the Ryukyu Kingdom continued to dispatch tribute envoys to Qing China. At the same time, it sent envoys to Tokugawa shoguns in Edo (present-day Tokyo). Ryukyu relations with Korea also continued.

After the Ryukyu Kingdom was abolished and the Ryukyus became a Japanese prefecture in 1879, Naha, which had been an important trading port linking the Ryukyus with East and Southeast Asia, lost these linkages and a new treaty port system emerged through treaties with western countries. Ryukyu trade was thereafter routed exclusively through Japan, and Japanese merchants controlled much of it. Hong Kong and Singapore played important roles in the emerging treaty port system that would redirect trade routes throughout Asia and between Asia, Europe and the Americas.8

The era of negotiation in the tributary-trade zone

From the 1830s to the 1890s the nations and regions of East Asia entered a period that can be called the era of negotiation, one characterized by multilateral and multifaceted intra-regional negotiations. The origins of the historical issues that the era poses can best be grasped not from the conventional perspective of Asia’s “forced” opening from the “impact of the West,” but rather from a perspective that focuses on internal changes in the East Asian region.

Changes in the historical international order of East Asia began with adjustments in the tribute relationships centered on the authority of the Qing emperor. Tributary states and trading nations (hushi guo) on the periphery of the Qing empire, based on their newfound economic strength, no longer strove to maintain as close a relationship with the Qing as before, and in each of them internal conflicts erupted between reformist and conservat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Notes On Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Rise of East Asia In Regional and World Historical Perspective

- Chapter 1: Tribute and Treaties: Maritime Asia and Treaty Port Networks In the Era of Negotiation, 1800–1900

- Chapter 2: A Frontier View of Chineseness

- Chapter 3: The East Asian Path of Economic Development: A Long-Term Perspective

- Chapter 4: Women’s Work, Family, and Economic Development In Europe and East Asia: Long-Term Trajectories and Contemporary Comparisons

- Chapter 5: The Importance of Commerce In the Organization of China’s Late Imperial Economy

- Chapter 6: Japan, Technology and Asian Regionalism In Comparative Perspective

- Chapter 7: Historical Capitalism, East and West