![]()

1 Introduction

This survey of the moral topography of Jihad suggests that McWorld—the spiritual poverty of markets—may bear a portion of the blame for the excesses of the holy war against the modern; and that jihad as a form of negation reveals Jihad as a form of affirmation. Jihad tends the soul that McWorld abjures and strives for the moral well-being that McWorld, busy with the consumer choices it mistakes for freedom, disdains. Jihad thus goes to wars with McWorld and, because each worries the other will obstruct and ultimately thwart the realization of its ends, the war between them becomes a holy war.

(Benjamin R. Barber 1995: 215)

The opening decades of the twenty-first century may be compared to the dark decade of the 1930s. This may be a dress rehearsal for a major human tragedy in which terrorism and weapons of mass destruction will play critical roles. The chasms in the material and cultural conditions between the five layers of human civilization discussed in this volume may be widening. Except for a few nations possessing a history of cultural integration and political unity, most may find it difficult if not impossible to hold on and catch up. In some countries, such as Iraq, tribalization of politics is visible. In Western Europe, tribalization is simmering under the surface and may explode at any time. Witness France mobilized along ethnic lines in November 2005. In contrast to the New World, which was based on immigration, Europe’s immigrants came from the former colonies and have been segregated into ghettoes. In the French case, this spells out the banlieue, the city suburbs. Denial of respect and welfare is leading to explosive social relations.

Tribalization may be considered as part of the unfinished democratic revolution that began with the modern revolutions in Britain (1644), the United States (1776), France (1789), Russia (1905 and 1917), China (1912 and 1949), and Iran (1905 and 1979). As the repressed layers of population1 come to historical consciousness, they demand autonomy, sovereignty and yes, dignity. The dominant ethnic groups, such as the Sunnis in Iraq, normally refuse to give up power peacefully. Thanks to the leadership of Mandela and de Klerk, South Africa was an exception to this rule. A bloodbath was avoided.

Bloodbaths are blueprints for tragedy. Cycles of violence tend to continue. Witness the tragedy in Palestine–Israel. Increasingly transformed into a small global village, an uneven world will have to be divided into its gated castles and their surrounding lawless countryside. The availability of weapons of mass destruction to the powerful and the power aspirants will make the world a more dangerous place. Unless a more democratic method of global governance is found, interventions of superpowers will not be adequate to the challenge of maintaining some measure of peace, fairness, and even security.

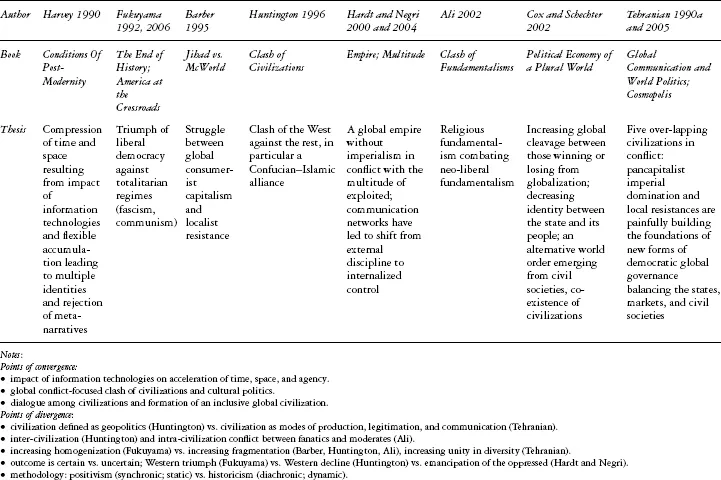

This volume attempts to make sense of the post-Cold War era. But it has done so in the context of the long and unfinished history of civilization. Defined as a normative construct for the pursuit of peace with peaceful means, human civilization remains the human family’s best hope for survival. Table 1.1 summarizes the perspectives of some of the authors who have achieved prominence in the on-going international discourse. Unsurprisingly, most of the eight authors are American. Imperial domination demands ideological legitimation. Due to the rise of English as a global lingua franca, however, other voices also can be heard. The list is arbitrary, but not too arbitrary. In the current global conversation, it attempts to situate the thesis of this volume among those that have preceded it. Despite profound disagreements among the foregoing authors, we can decipher a significant consensus. Before examining the possibility of a consensus, however, let us review the differences.

Theories in search of complex realities

In his Conditions of Post-Modernity, David Harvey (1990) provided a multidisciplinary analysis of the coming world, which he and others have labeled “postmodern.” In contrast to the modern world, the postmodern world may be considered to have the following features: first and foremost, the postmodern world is characterized by an acceleration of time, space, and agency. Harvey covers the first two features under the rubric of “compression of time and space.” The diffusion of information technologies has radically changed global production and communication. It has made “flexible accumulation” possible. The transnational corporations (TNCs) no longer have to concentrate their production in one locality. In order to gain greater efficiency and competitiveness, they can spread it around the world where the costs of capital, labor, rent, and government regulation are lowest. I might add that the greater flexibilities of production (e.g. modular, just in time, and post-Fordist assembly line) have opened up possibilities for greater agency at the individual and collective level. States have been able to jump on the bandwagon of globalization, gain access to sources of capital, markets, and management. Countries can achieve technological leapfrogging. The East Asian economic miracles can be best understood in this light. Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, and China have been demonstrating how to leapfrog by entering into partnerships while maintaining their identities. Individuals also have leapfrogged from lower to higher incomes by the same method.

Table 1.1 Eight visions in search of the post-Cold War realities

The emergence of cultural politics in the post-Cold War era has been recognized by many authors. Among the theorists of the post-Cold War era, Huntington has received the greatest attention. He provides a comprehensive and well-researched analysis of the post-Cold War trends. In the tradition of the realist school of international politics, Huntington’s concept of civilization is essentially geopolitical. He identifies a mix of nine geopolitically-defined civilizations, including Western, Latin American, Islamic, Sinic, Hindu, Orthodox, Buddhist, and Japanese. But, in the colonialist tradition, he considers Africa to be primarily tribal and not quite “civilized”!

In response to Francis Fukuyama’s (1989) declaration of Western liberal capitalist victory and The End of History, Huntington is deeply pessimistic and concerned about Western decline and the rise of a Confucian–Islamic alliance against the West. He turns out to be a cultural determinist. Like economic determinists, he enlightens but he also obscures. His section on Islam’s bloody borders (pp. 254–265) is a remarkable example of historical amnesia. He neglects the Western periodic interventions, motivated by preoccupation with oil, Israel, and pro-Western dictatorships. Such interventions have often derailed a more indigenous political development in the Middle East and North Africa.

In his more recent book, America at the Crossroads: Democracy, Power, and the Neoconservative Legacy (2006), Fukuyama seems to recant. Having observed the messianic zeal of a US Administration with dismay, Fukuyama seems to revoke his neoconservative credentials. As a New Yorker (Menand 2006: 84) review suggests,

The End of History understood the outcome of the cold war in a spirit quite different from that of the standard neo-conservative account, according to which we [i.e. the United States] won the cold war because Reagan adopted a policy of liberationist interventionism. We changed the political regimes in Russia and its satellites, and the pieces of a liberal society just naturally fell into place there. Fukuyama thinks that we won the cold war mainly because an unworkable system reached its inevitable point of collapse, helped by the actions and inactions of Mikhail Gorbachev, that, apart from oratory and some funding of predemocracy groups, we did little in the way of intervention; and we ought to thank our stars and decline to draw grand policy lessons. Grand lessons were drawn, though, and that is why so many American intellectuals believed that regime change in Iraq was not only readily achievable but cosmically mandated.

However, Huntington’s theory of a clash of civilizations provided an easily understood and empirically “validated” explanation of the new forms of conflict between “the West and the rest” (Huntington 1996: 33). The theory caught the imagination of the centers of power in Washington and elsewhere. There are numerous problems with Huntington’s mapping of the post-Cold War era. For instance, it is a portrait focusing on competitive rather than cooperative security. Second, China, Japan, and Korea should properly be considered part of the same civilization. From a geopolitical perspective, they have taken different courses of development and alignments. At the deeper level of cultural analysis, the three countries still share common historical memories, linguistic affinities, and collectivist trends in values and behavior. Japan after the Meiji Restoration, China after the communist revolution, and Korea after partition, each has taken a different course of political development, but are now coming closer together.

Nevertheless, 9/11 and subsequent events have endowed Huntington’s thesis with the mystique of prophecy. In the short run, he seemed right. The rise of identity politics in many parts of the world (USA, India, China, Russia, and the Islamic world) must give us pause. However, Huntington’s analysis is basically static and flawed. True enough, as compared with technological and economic transformations, cultures change at a snail’s pace. The function of cultural life is to maintain continuity and identity over time. That is why cultural life is essentially conservative. But in response to technological and economic pressures, cultures do change. And that’s where Huntington may be unrealistic, one-dimensional, and misleading.

Huntington’s analysis is strong on cultural politics and weak on political economy. Other scholars have come to the rescue. Robert W. Cox has identified empires, states, and social movements as the three major historical forces that are currently shaping our destiny. Empire is represented by the United State hegemony in the post-Cold War era. As represented in the United Nations and other inter-governmental organizations (IGOs), the state continues to be a force that limits the extent and power of the empire. Social movements represent the global civil society in formation. They are another check on imperial ambitions. Cox (2002) calls for co-existence among civilizations. He points to the decline of the state system, the rise of transnational corporations, and the ascendance of civil societies as the most important elements in a new world order.

Chua (2003) points to the genocidal aspects of colonization, modernization, and globalization. The three historical sequences have bred a class of comprador bourgeoisie in the post-colonial countries that are on the forefront of modernization and globalization. This class often constitutes a visible ethnic or religious minority. It suffers therefore the brunt of the post-colonial anger of the masses. The Tutsis in Rwanda, the Chinese in Southeast Asia, the Bahaiis in Iran, the Arabs in West Africa, and before them, the Jews in Eastern Europe have suffered genocide. They are the pioneers who have often sided with the colonialists to dominate the indigenous peoples, or at least that is how they are perceived in the post-colonial years. Chua concludes that capitalist extensions in the less developed countries often breed genocide against such minorities.

Castells (1996–2000) provides a comprehensive and detailed account of the post-war years. He argues that a network society is taking the place of industrial civilization. Erudite and persuasive, the argument put forth by Castells must be weighed against all the other networks in past historical epochs. The new networks are electronic, disembodied, and fast-paced. They are frequently extensions of the past social networks. They seem to be powerful only to the extent that they can connect with the face-to-face networks

Jerry Bentley (2004) has similarly argued that the human journey is marked by three great ambitions: empires, businesses, and missions. Empires represent the ambition to build domination over vast territories. Business refers to, as Adam Smith put it, “the human propensity to tuck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” Mission suggests the complex variety of efforts to convert others to one’s own belief system. He is reluctant to employ “civilization” as a concept because it has been so badly abused for hegemonic purposes often by violent means. Bentley calls for globalizing history and historicizing globalization, to which this volume responds.

Barber’s contribution to this discourse has been to identify already a competition between the two most important global pathologies: McWorld versus Jihad. To avoid localized identities, I have opted to call them, more abstractly, commodity and identity fetishism. But as rising state and opposition terrorism has amply demonstrated, we are witnessing a new kind of security fetish, a reminder of the inter-war period (1919–1940). History repeats itself, yes, first as tragedy, but if we do not learn, as yet another tragedy.

Hardt and Negri present an unlikely team of authors. An American professor of Literature has collaborated with an imprisoned Italian communist leader to write two books of immense size and elegant prose devoted to an explication of our brave new world. Their central thesis appears to be that we are witnessing the rise of a new world empire without imperialism. How can we have an empire without imperialism? The invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq undermine the thesis. But the volume has considerable merit in recognizing that the new “digital empire” (my terminology) is significantly different from the imperial systems of the past. It is global, it cuts across territorial boundaries, and divides each nation from within between its digital and predigital populations. Although old-fashioned geopolitical rivalries continue, the new digital empire has an imperialist ambition to conquer all parts of the world. President Bush’s inaugural address of January 20, 2005 left no doubt about that ambition. As revolutionaries, Hardt and Negri pin their hope on the multitude (2004), the subject of their most recent publication.

Tariq Ali (2002) provides a punchy, journalistic, and personal account of the shape of the world that refutes Huntington’s theoretical speculations. He is not shy in telling the truth of the Afghan, Pakistan, and Iraq wars. We learn that the United States along with its allies, the governments of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, virtually created the so-called “terrorist” guerrillas in 1980s as “freedom fighters” to battle the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. The United States also supported Saddam Hussein in his war against Iran. Those truths are completely concealed by the fog of war and ideology in the American media and Huntington’s narrative.

Jared Diamond is a UCLA physiologist. He goes back into history to explain the contemporary world. In his earlier book (1997) he tried to explain the contemporary chasms among nations today. His explanations are always original and fascinating. They focus on the role of guns, steel, and germs in the fate of human societies. His most recent book, The Collapse (2004), explains how and why civilizations collapse. They do so primarily by destroying their own natural environment as in Easter Island or contemporary America. His observations about American society as revealed in Southern California are sobering. The most affluent in the United States live today in gated communities, ride gas-guzzling SUVs, and drink their water out of manufactured bottles, sometimes imported from France (Perrier). With two-thirds of the world’s population living on two dollars a day, the affluent are contributing their share to a coming upheaval that will have ecological and social dimensions.

The unfinished journey

This volume puts the current problems into a larger historical context. As a result of Europe’s pioneering modernization path, the rest of the world has had no choice but either to modernize or be colonized. The United States led the way by the American Revolution of 1776 to liberate itself from the British yoke. In order to catch up, the communist and socialist states took a short cut by concentrating economic and political power into the hands of the state. Having built an infrastructure necessary for the free markets to operate, Russian, Eastern Europe and China have joined the global markets during the last two decades. Societies that are further behind such as those in Africa, Asia, and Latin America are currently struggling to catch up with a variety of market and state regulations. For example, Iran is trying to reach the same catch-up goal on the basis of Islamic precepts. In the meantime, globalization is taking its merry but devastating course. Accelerating fragmentation, tribalization, and cultural politics are its consequences. However, globalization is also encouraging the development of global consciousness, networks, and citizenship. This volume triangulates the historical process of globalization in terms of modes of production (chiefly technological and economic), modes of legitimation (mainly ideological and political), and modes of communication (largely cultural).

As a normative concept, civilization may mean the pursuit of peace with peaceful means (Galtung et al. 2000). The contradiction between empires and civilizations appears to be a constant factor in history. Empires often employ military might to achieve territorial and juridical domination. By contrast, civilizations contain normative standards for humane governance.

However, the genealogy of the term “civilization” is deeply embedded in the rise of Western empires. The term “civilization” was conceptualized in modern European history to make distinctions between us and them, the civilized and the barbarian (Mazlish 2004: 14–20). Proponents of European, Russian, American, and Japanese empires have argued that the more advanced states and peoples have a moral mission to extend the benefits of civilization to the “savages and barbarians,” which was often called “the White Man’s Burden.”2 Knowingly, the poet laureate of colonialism, Rudyard Kipling, recognized that equality of power blurs all differences:

Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God’s great Judgment Seat;

But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth,

When two strong men stand f...