This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The top names in the field come together in this collection with original essays that explore the link between gender and racism in a variety of racial and white supremacy organizations, including white separatists, the Christian right, the militia/patriot movements, skinheads, and more.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Home-Grown Hate by Abby L. Ferber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Mapping the Political Right: Gender and Race Oppression in Right-Wing Movements

Right-wing hate groups do not cause prejudice in the United States—they exploit it. What we clearly see as objectionable bigotry surfacing in extremeright movements is actually the magnified form of oppressions that swim silently in the familiar yet obscured eddies of “mainstream” society.1 Racism, sexism, heterosexism, and anti-Semitism are the major forms of supremacy that create oppression and defend and expand inequitable power and privilege; but there are others based on class, age, ability, language, ethnicity, immigrant status, size, religion, and more.2 These oppressions exist independent of the extreme right in U.S. society.

Bigotry and prejudice are easy to find in the texts of various right-wing movements in the United States, but they occur in varying degrees in different groups and can change over time. Between the hate-mongering groups of the extreme right and the reform-oriented groups in the conservative right are a series of dissident-right social movements. Examples include the Christian right and the patriot movement (which includes the armed citizens’ militias).

Some scholars study the dissident right and extreme right and treat them as a single entity for analytical purposes. In one sense this is fair: both the dissident right and the extreme right have stepped away from politicians, elections, and legislation where the political movements and institutions of the conservative right are most active. Many scholars and activists refer to all right-wing movements outside the electoral system as the far right or the hard right. This chapter will use the term hard right in this manner, to cover both the dissident right and the extreme right.

While it is sometimes appropriate to discuss similarities in the various movements in the hard right, too often very real differences are minimized, ignored, or dismissed. The terminology and definitions used to describe hard-right groups are sometimes applied in an overbroad or confusing manner. Some of the work conflating the dissident right with the extreme right uses guilt by association or fallacies of logic in ways that would be more obvious (and raise more objections) if the groups being examined were not held in such low esteem in academia and the general public.

This is not to apologize for supremacist bigotry in the U.S. political right, but to argue that the specific ideology and the types and degrees of prejudice, supremacy, and oppression are important distinctions to be observed, since they vary greatly depending on the sector of the hard right under inspection. This variance is so significant that the Christian right, patriot movement, and extreme right should be studied as autonomous social movements. Later in this chapter, the commonalities and differences among these three sectors of the right will be examined in detail, along with critical comments concerning previous research, including my own.

Coming to Terms with Right-Wing Movements

It is not useful to lump together all right-wing dissident groups outside the mainstream as “far-right hate groups” or “religious-political extremists.” If scholars presume to study demonization as socially dysfunctional, we should scrupulously avoid it in our own work. Not all forms of prejudice rise to the level of hate. Not all scapegoating calls for genocide. Not all forms of sexism qualify as misogyny. Not every group that defends heterosexism is a hate group. To some observers the Christian right, the patriot movement, and the armed militias may seem far to the right; but it is neither accurate nor fair to claim they are identical to neo-Nazis or other race-hate terrorists.

When talking about the hard right, we need to discuss as shared attributes only those attributes that are actually shared by all the different sectors. It is true that scholars often can find some similarity in the ideologies, styles, tools, frames, narratives, or targets utilized across the hard right. What is neither useful nor accurate is the tendency to discover a distinct aspect of one movement, such as the extreme right, and then extrapolate it across all movements in the hard right. If the same features are identical in the extreme right, patriot movement, or the Christian right, then some evidence needs to be presented. In addition, all sorts of people occasionally make prejudiced statements. Locating one prejudiced statement by an individual is not convincing evidence that the statement represents the ideological worldview of the individual. In the same way, finding a member of a movement or group who utters prejudiced or hateful statements is not convincing evidence that the member’s view represents the ideological worldview of the group itself or even most of its members. Maybe it does, maybe it does not—evidence is required.

When writing about the social evils of prejudice and oppression, the devil is in the details. Many older studies of prejudice had a “tendency to collapse distinctions between types of prejudice” observes Elisabeth Young-Bruehl. They assumed “that a nationalism and racism, an ethnocentric prejudice and an ideology of desire, can be dynamically the same.” Furthermore, she writes, “there is a tendency to approach prejudice either psychologically or sociologically without consideration for the interplay of psychological and sociological factors.”3 In a complementary fashion, Steven Buechler notes that issues of class, race, and gender are “omnipresent in the background of all forms of collective action” and reflect “institutional embeddedness within the social fabric at all levels.” But he adds that these are distinct yet overlapping structures of power that need to be assessed both independently and jointly. To do this, it is important “to theorize the different, specific, underlying dynamics that distinguish one structure from another.”4 Ultimately, the successful assertion of “collective human rights” or “group rights” depends on the “linking of ethnicity/race, class, gender, and sexuality,” argues William Felice, because this linkage “mutes supremacist tendencies by denying the right of any one group to assert supremacy over a different group.”5 For brevity, this constellation of identities is sometimes referred to as race, gender, and class.

To unravel systems of oppression involving race, gender, and class, we need a more complex formula that is better at mapping out the dynamics of societal oppressions in ways that resonate with the everyday experiences of our colleagues, students, neighbors, and families. This is especially important in an era of open hostility to discussions of supremacy, domination, and oppression. Developing a concept of “racial formation “Michael Omi and Howard Winant argue that “racial projects” that are “racist” entail a linkage between “essentialist representations of race and social structures of domination.”6 They further argue that “racial ideology and social structure” act in an interconnected and dialectical manner to shape racist projects.7 Applying these concepts to racism, sexism, and heterosexism, I think it is useful to define societal oppression as the result of a dynamic process involving ideas, acts, and a hierarchical position of dominance that is structural. The dominance enshrined in “social structures of domination” involves both unequal power and privilege. The resulting formula is as follows: supremacist ideology +discriminatory acts+structural dominance=oppression.8

In studying groups that promote oppression, scholars need to identify discrete components of ideology, methodology, and intent in order to classify and explain more accurately how different social movements function. Increased attention to specificity in language, categorization, and boundaries can assist our analysis of oppressions promoted by the hard right. By tracing the similarities and differences among hard-right movements and charting the dynamic relationships among the various sectors, we not only better understand movement dynamics but also learn how to construct a more effective counterstrategy to defend and extend freedom and equality.9

Terminology and Boundaries

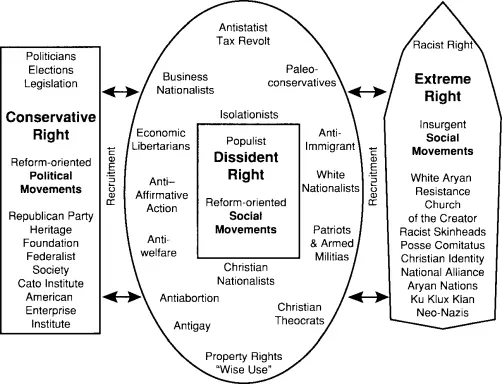

A number of scholars who have studied the contemporary hard right already use a range of careful distinctions.10 However, Martin Durham has called for scholars to pay even greater attention to precision in terminology when analyzing right-wing political groups.11 Many analysts, especially in Europe, see the landscape of the political right as involving three major sectors, with some sort of dissident (often populist) sector between the conservative right and the extreme right.12 Figure 1.1 shows how these sectors interact.

Fig. 1.1 Adapted from Right-Wing Populism in America (Berlet and Lyons, 2000)

Note that Christian nationalists are closer to the conservative right (an example would be the legislation-oriented Free Congress Foundation), as opposed to Christian theocrats (such as the group Concerned Women for America), who promote more antidemocratic agendas. The most militant and doctrinaire Christian-right groups, such as those that embrace Christian Reconstructionism, actually fit best under the banner of the extreme right.13

The term extreme right refers to militant insurgent groups that reject democracy, promote a conscious ideology of supremacy, and support policies that would negate basic human rights for members of a scapegoated group. The terms extreme right and racist right are often used interchangeably, although for some groups on the extreme right gender is also a major focus, and racism exists in various forms and degrees in all sectors. Extreme-right ideologies of overt white supremacy and anti-Semitism envision a United States based on unconstitutional forms of discrimination. Extreme-right groups are implicitly insurgent because they “reject the existing political system, and pluralist institutions generally, in favor of some form of authoritarianism.”14 In contrast, dissident-right groups still hope for the reform of the existing system, even when their reforms are drastic and the dissidents are skeptical that their goals will be reached. The term “hate group” describes an organization in any sector that overtly and aggressively demonizes or dehumanizes members of a scapegoated target group in a systematic way.15 The term “extremist” is of dubious value and not used in this chapter. As Jerome Himmelstein argues, “At best this characterization tells us nothing substantive about the people it labels; at worst it paints a false picture.”16

When analyzing a movement or group, we must ask a whole series of questions: What are the main public issues and what are the subtexts? What is overt and what is covert? What is intentional and what is unintended? What is conscious and what is unconscious? What are the degrees of prejudice and what are the degrees of discrimination? How different are the ideologies and actions from those of “mainstream” society? This last question is especially important when looking at historic movements because, while it is fair to judge these earlier movements by today’s standards, it also is necessary to locate the group in its historic context.

Commonalities

One reason that differences and boundaries within the hard right are often overlooked is that hard-right groups not only can share the same targets for scapegoating but also can use common styles, frames, and narratives. In addition, since the late 1970s, mobilization by the hard right in the United States has been assisted by a widespread heteropatriarchal identity crisis. Before I argue the differences, I need to exami...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Mapping the Political Right: Gender and Race Oppression in Right-Wing Movements

- 2. Women and Organized Racism

- 3. “White Genocide”: White Supremacists and the Politics of Reproduction

- 4. Normalizing Racism: A Case Study of Motherhood in White Supremacy

- 5. The White Separatist Movement: Worldviews on Gender, Feminism, Nature, and Change

- 6. “White Men Are This Nation”: Right-Wing Militias and the Restoration of Rural American Masculinity

- 7. “Getting It”: The Role of Women in Male Desistance from Hate Groups

- 8. The Dilemma of Difference: Gender and Hate Crime Policy

- 9. Green or Brown? White Nativist Environmental Movements

- Afterword: The Growing Influence of Right-Wing Thought

- Notes

- References

- Contributors

- Index