eBook - ePub

Creating Sanctuary

Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies, Revised Edition

This is a test

- 340 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Creating Sanctuary is a description of a hospital-based program to treat adults who had been abused as children and the revolutionary knowledge about trauma and adversity that the program was based upon. This book focuses on the biological, psychological, and social aspects of trauma. Fifteen years later, Dr. Sandra Bloom has updated this classic work to include the groundbreaking Adverse Childhood Experiences Study that came out in 1998, information about Epigenetics, and new material about what we know about the brain and violence.

This book is for courses in counseling, social work, and clinical psychology on mental health, trauma, and trauma theory.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Creating Sanctuary by Sandra L Bloom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Trauma Theory

Deconstructing the Social

And truly, now we see through a glass darkly, not face to face.

The Confessions of St. Augustine, Saint Aurelius Augustine, 401 A.D.

Introduction: 1997–2013

When I first wrote this book, the basic knowledge about trauma was still very new, and in this chapter I summarized what I had learned up to that point, information I thought was critical knowledge for everyone. Trauma Theory became one of the four pillars of the Sanctuary Model and continues to be today. In the last fifteen years, there has been an explosion of research, knowledge, experience, and literature about the issue of trauma exposure, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the treatment of trauma. I have not attempted to fill in all those gaps. I think Dr. Dan Weiss summarized what we have learned, especially from the past ten years after the World Trade Center Disaster, when he wrote in a special issue of the Journal of Traumatic Stress Studies:

It is a truism to note that this man-made terrorist disaster fundamentally, and permanently, altered the world view of the citizens of the United States, at least those who were old enough to appreciate its meaning. For the latter, however, their world view has always included the reality of the collapsing WTC towers and its horrible aftermath. It is also fair to say that the world view of citizens of many other countries around the world was also fundamentally and permanently altered. Victims of 9/11 came from over 70 countries. As well, 9/11 propelled emergency services workers (e.g., police, firefighters, and search and rescue personnel) and the role they play in disasters into the forefront of associations with 9/11. The 9/11 attacks also increased public awareness of the psychological processes that are required to adapt to and recover from exposure to traumatic stress and that such processes can be, blocked, derailed, or overwhelmed. [1]

I have updated some of the references, added a summary of the very important Adverse Childhood Experiences Study that did not come out until 1998, added some beginning information about epigenetics, and covered some new material about what we know about the brain and violence.

What has, however, emerged in the past fifteen years is a problem with the language we use. The word “trauma” often arouses very specific images and feelings in people, like the permanently engraved images of 9–11, meaning discrete, time-limited events that are usually life-threatening. Defined in this way, it is not difficult for people to understand that such events could damage people. But the people we saw in the Sanctuary programs, and most of the people who have been profoundly affected by something, have not been exposed to a discrete, time-limited event; instead they have been exposed to bad things happening to them over and over and over, beginning when they were too young to do anything to self-protect, and the adults around them, in some way or another, failed them. They may have had discrete traumatic events as well, but those are not as likely to have made the events a central organizing context for their lives. It is the exposure to “toxic stress” and the “allostatic load” of living in chronically terrible circumstances that have produced the complex problems they live with every day. We do not have a word in English that combines “trauma”, “toxic stress” and “allostatic load”, so we find ourselves in a language dilemma, repeatedly hastening to explain what we really mean when we use the word “trauma”.

The best we have come up with so far is the notion of “complex traumatic stress disorders”, a term that now is widely used, is usually applied to adults, and which refers to “experiences or events that (1) are repetitive, chronic, or prolonged; (2) involve harm, such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and/or neglect or abandonment by parents, caregivers and other ostensibly responsible adults; and (3) occur at developmentally vulnerable times in the person's life, especially over the course of childhood, and become embedded in or intertwined with the individual's development and maturation” (p.442) [2]. Similarly, the complex trauma work group of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) has advanced a potential new diagnosis – Developmental Trauma Disorder – for complexly traumatized children. There is hope that the next (fifth) edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual will include both of these. If it does, then the diagnostic scheme – and the insurance reimbursement schemes that accompany it – will finally reflect the problems that most clinicians actually see in their practices [2]–[7].

Through a Glass Darkly: The Theory of Trauma

In ways vastly more complicated than any computer, the human organism is designed to function as a unity, an integrated and interconnected whole. Unfortunately, our ability to think clearly, logically, and in an integrated way is vulnerable to a multitude of stresses. These stresses can be biological, psychological, social, or moral, or any combination of these. Regardless of the kind of stress, our capacity for clear thinking is constantly jeopardized by physiologically based bodily and emotional reactions, over which we have little control and about which we often have little awareness. Any kind of overwhelming stress produces fragmentation, and, like Humpty Dumpty, the pieces often elude reunion.

It is this fragmentation, or loss of normal integrated functions, that is at the heart of understanding the impact of overwhelming stress. Once we understand that the brain – not just the mind – is overwhelmed at the time of an event and does not perform its normal integrative processes, then all else begins to fall into place. It is when we are severely stressed, when the expected routine of daily life is disturbed by traumatic events, that our bodies respond in primitive ways, and we find ourselves in the midst of a storm of emotional and physical reactions that we cannot understand or control. In many ways, we are not the same people when we are terrified as when we are calm. Our bodies change in remarkable ways, as do our perceptual abilities, our emotional states, our thought processes, our attention, and our memory. When under this kind of stress, it is as if we become another person, no longer able to respond to others as we would under less threatening circumstances.

Compared with other animals, humans are astonishingly vulnerable to their environment. We cannot run very fast, our fingernails are poor substitutes for claws, our skin offers little resistance to the vicissitudes of weather, we have no poisonous fangs. We are, however, “set” internally to respond to situations of danger more readily than situations that evoke feelings of contentment, satisfaction, or joy. Like other animals, we are biologically equipped to protect ourselves from harm as best we can. But even with our superior brains, an early human standing alone against a dangerous foe had very little defense. Our ability to form attachments to each other and form social groups has been our best defense and has guaranteed our survival. Attachment to our social group is a deeply ingrained structure that derives from our primate heritage.

In the next two chapters I will lead the reader through a condensed process of re-education similar to the one my colleagues and I experienced over the course of several years. We are still looking “through a glass darkly”, because there is yet so much to be learned.

I am going to look at what happens to the body, the mind, the emotions, the social identity, the behavior, and the meaning system of people who are exposed to experiences of terror, most particularly terror that is unrelenting, repeated, severe, or secret. Then, I am going to begin building a case for the “antidote” – the capacity of human relatedness to provide the healing integration that is necessary if the victim is to transform suffering into victory.

Background

The most persistent sound which reverberates through man's history is the beating of war drums.

Arthur Koestler, 1978, Janus

Accounts of the effects of overwhelming stress on the body, mind, and soul of the victim go back at least as far as Ancient Greece, whose writers had a great deal to say about combat, traumatic death, grief, horror, guilt, betrayal, and tragedy [8]–[10]. Likewise, women have described experiences with domestic violence and child abuse since at least the twelfth century [11]. Shakespeare knew well the signs and symptoms of states of terror, and in 1666, Samuel Pepys described post-traumatic stress disorder in depicting people's reactions to the Great Fire of London. Over the years, post-traumatic stress disorder has had many names – hysteria, soldier's heart, psychic trauma neurosis, shell shock, physioneurosis, combat fatigue, railway spine disorder, battle fatigue, traumatic neurosis, survivor's syndrome, rape trauma syndrome, battered child syndrome, battered wife syndrome [12].

In the last century, knowledge of the effects of psychological trauma has twice surfaced in public consciousness and been lost again [13]. Each time awareness has grown, it has been in connection with a sociopolitical movement that gave it support. The first emergence was the study of hysteria in the late nineteenth century that grew out of the republican, anticlerical political movement of late nineteenth-century France. Freud and his colleagues noted a strong connection between the psychiatric symptoms of “hysterical” women and a personal history of sexual molestation. But he became increasingly concerned about the sociopolitical implications of his observations. It was not credible that there could be so many adults molesting children. In place of the real events of women's lives, he substituted sexual fantasy. As Dr. Herman summarizes, “Sexuality remained the central focus of inquiry. But the exploitative social context in which sexual relations actually occurred became utterly invisible” (p.14) [13]. As a result, the connection between childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric disorder was buried for another century.

The study of trauma re-emerged as a result of the First and Second World Wars when so many soldiers and prisoners-of-war (POWs) returned with what was called “shell shock” in WWI and “combat fatigue” or “combat neurosis” in WWII. Just after WWII, researchers asserted that 200 to 240 days of combat was enough to break anyone [13]. Despite this, combat fatigue was still considered to be a result of individual weakness on the part of the soldier. Not until the 1970s did the reality of violence and its effects become central to our culture. This centrality derived largely from the problems of Vietnam War veterans who organized themselves outside of official governmental systems, paralleling a similar movement among American and Western European feminists whose concerns focused on violence toward women and children. Now we have an entire new generation of traumatized veterans – men and women – as a result of the wars in the Middle East that have been ongoing since after the World Trade Center attacks.1

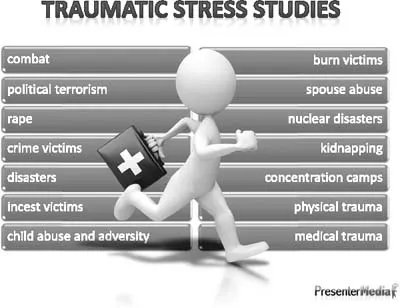

In 1980, the diagnosis of “post-traumatic stress disorder”, or PTSD, entered the formal psychiatric lexicon of the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual [14, 15]. Although quite limited in scope, the addition of a formal diagnosis for PTSD helped to move the field of traumatic stress studies forward. In 1985, the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies was founded to provide a forum for the sharing of research, clinical strategies, public policy concerns, and theoretical formulations on

Figure 1.1 Traumatic Stress Studies

trauma in the United States and around the world [16, 17] (Figure 1.1). Treatment guidelines have been formulated for PTSD and for dissociative disorders [18, 19].2 There is now an extensive literature on the subject of “Complex Post-traumatic Stress Disorders” and “Developmental Trauma Disorders” in an effort to extend the diagnostic categorization system to encompass the complex and interactive problems associated with exposure to childhood adversity and prolonged exposure to traumatic stress [2–7, 13, 20–28].3

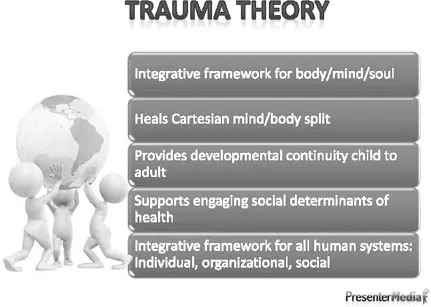

The result of this resurgence of interest in traumatic experience is trauma theory, a knowledge base that serves as an anchor for the integration of various psychological theories, techniques, and points of view, a possible “unified field theory” of human behavior (Figure 1.2). We cannot formulate effective strategies to deal with violence unless we have a common knowledge base that explains to us what trauma, adversity, and interpersonal violence actually do to the body, mind, and soul of the individual, and how that affects the group.

Poor Humpty-Dumpty

Nursery rhymes are said to have many meanings, but one explanation of the historical significance of this one was that Humpty-Dumpty was an English cannon that was destroyed by Parliamentary forces during the English Civil War, and that it was so broken that neither the King nor his Royalist forces could put it back together again. Lewis Carroll used the Humpty-Dumpty character in Through the Looking Glass, and added to Humpty's character development that he could not

Figure 1.2 Trauma Theory – An Integrative Framework

identify faces – an innate human characteristic that plays a significant role in the development of our social brain. Humpty-Dumpty is typically portrayed, however, as an egg – and the image of an egg cracking is a good representation of the loss of integrated function that accompanies a traumatic event and that helps to explain many of the subsequent difficulties.

Under normal circumstances, we are constantly responding to environmental stimuli, physically – with our bodies and all of our senses as well as emotionally and cognitively. But our brains perform the complex integration operations that comprise our experience of reality so smoothly that we do not perceive the separate nature of these functions (Figure 1.3).

Experience that is overwhelming does just that – it overwhelms the brain's capacity to do the more complex integrating tasks that have evolved across our evolutionary history, and we are reduced to forms of brain processing that originated much earlier in our species development (Figure 1.4).

In this state, the brain continues to take in a great deal of somatic, sensory, and emotional information, but this information is inadequately integrated into a coherent cognitively based narrative. This primary failure of integration helps to explain many of the subsequent problems that survivors endure as they try to cope with the immediate, short-term, and long-term aftermath of overwhelming exp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Fifteen Years Later, 1997–2013

- 1 Trauma Theory: Deconstructing the Social

- 2 Attachment: Constructing the Social

- 3 Remembering the Social in Psychiatry

- 4 Creating Sanctuary: Reconstructing the Social

- 5 Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies

- Notes

- References

- Index