![]()

Chapter 1

Partners in the Funding Relationship

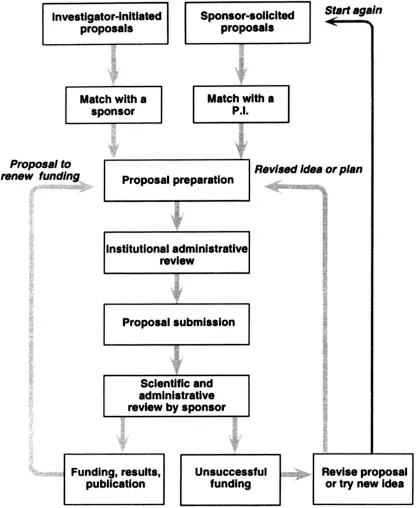

Successful, long-term research funding is grounded in the relationships that evolve explicitly between researchers and their sponsors and implicitly between researchers, sponsors, and society. Every strategic plan for achieving research funding must take into consideration these partners, their roles, and the interactions among them. A diagram of the overall funding process, in which research ideas—developed ideally within the context of a strategic plan-are translated into competitive proposals and ultimately into grant-or contract-funded research is shown in Fig. 1.1. The successful process explicitly unites a researcher, a host institution, and a proposal of significant scientific merit with a sponsor. The implicit link to society is the far-reaching benefit of scientific success.

ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS, CLINICAL RESEARCHERS, AND RESEARCH-ENTREPRENEURS

The first party in the relationship is the researcher: the basic sciences researcher in an academic or research institution; the clinician or physician scientist in an academic medical center; or the researcher-entrepreneur in the private business sector. In the United States today, there are more than 100,000 researchers in the brain and behavioral sciences representing a broad range of disciplines from education to neurology.

FIG. 1.1. Overview of the grants and contracts process.

Regardless of specific background, the researcher’s role is to pursue new knowledge and information in the context of existing knowledge, with the object of at least incrementally enhancing the knowledge base in a particular domain. Science is thus advanced through ideas, proposals, funded research, results, and the dissemination of information. In the case of small businesses, science also yields a tangible commercial product.

During the 1960s and 1970s, researchers were considerably less susceptible to economic forces outside the academic or research institution than they are in the 1990s. Funding rates for basic research at that time were about 40%, renewal of a grant was a reasonable expectation, and many grants had a life cycle of 20 years or more. Steady scientific progress by a researcher was generally accompanied by a reasonable amount of dependable funding. The competition for funds in the 1990s is much more intense, however, and scientific merit must be accompanied not only by an underlying desire to make important contributions to society but, also, by skilled planning to enable it. The creation of a research funding plan, therefore, is an important step for a researcher at any point in a research career.

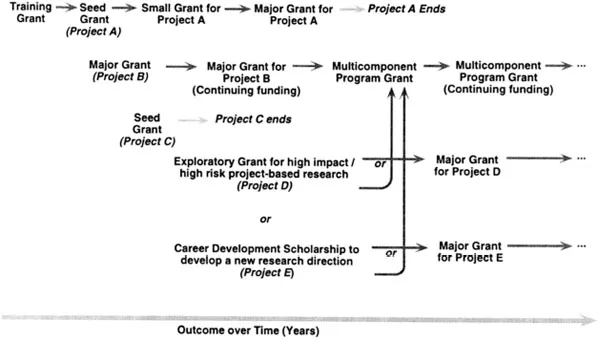

Figure 1.2 illustrates a systematic, albeit idealized, funding plan. As shown, the opportunities available either to the starting or to the experienced researcher are numerous. Each step in a funding plan should consider researcher eligibility in terms of career stage and type of opportunity, especially so that one opportunity does not preclude another (e.g., as in the case of a sponsor who will not fund a researcher who has already exceeded a certain threshold of support). Each step must also consider direct scientific and operational (e.g., personnel and equipment) needs. The outcome of each step will depend on the research timeline, progress, and results.

The execution of a funding plan draws the researcher into the world of sponsors. Sponsors are the researcher’s target audience for ideas (expressed through proposals) and progress (expressed through regular reporting). For the researcher, selecting from among the many possible sponsors involves searching not only for a valid scientific match but, also, for a career match because the evolving, bilateral relationship can impact both the scientific direction of the research and the specialized professional circles to which the researcher belongs.

SPONSORS

Government Sponsors

Sponsors differ in configuration and size. They operate for the purpose of promoting progress in the areas that are important to them. In the United States, the federal government is the largest sponsor of basic research at research institutions and provides about 60% of the funding for those institutions. For health and medicine, the largest government sponsor in the United States is the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH has approximately 30 institutes and centers representing widely varying interests and priorities. In 1998, for example, there are approximately 15,000 researchers funded by NIH, 2,000 reviewers, and hundreds of contexts in which health-related research is being pursued. This vast sponsor’s budget is more than $12 billion, with target funding priority areas in AIDS, breast cancer, molecular imaging, and minority health.

FIG. 1.2. Hypothetical long-term research funding plan and outcome. As a research program grows, parallel opportunities can be pursued strategically depending on the goals and success of the ongoing activities within the program.

The interests and priorities of other government agencies, both within and outside the United States, are equally broad and varied. For example, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) provides overall support for education in science and engineering and for academic research infrastructure such as instrumentation and facilities modernization, especially as it applies to improving educational and training opportunities. Unlike NIH, whose purview is research for the improvement of health and health care, NSF’s mission is to support the basic sciences. With a current budget of more than $3 billion, NSF supports almost 20,000 research and education projects in science and engineering (http://www.nsf.gov). In Canada, the major funding source for biomedical research is the Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC). With its $230 million budget, the MRC promotes basic and clinical research, as well as training of health scientists. Its counterpart, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), is the national source of funding in science and technology, with more than 11,000 supported Canadian researchers (http://www.nserc.ca). In Europe, national agencies such as the Swiss Federal National Science Foundation (SNSF), promote research at academic and scientific institutions. The SNSF distributes 75% of its approximately $300 million budget and almost 2,500 grants in the areas of humanities and social sciences, mathematics, natural and engineering sciences, and biology and medicine (http://www.snsf.ch).

Nongovernment Sponsors

In contrast to government sponsors, nongovernment sponsors such as foundations have considerably smaller budgets and narrower areas of interest and priority. There are approximately 40,000 foundations in the United States, divided into four types: independent, corporate, operating, and community foundations (Rich, 1996).

Independent Foundations. Independent foundations are supported by individuals and families, and are operated either under the voluntary direction of the principals or by a board of trustees and professional staff. Areas of scientific interest for extramural support are predefined; geographical restrictions may also apply, depending on the foundation.

Corporate Foundations. Corporate foundations, together with independent foundations, represent the large majority of the 40,000 foundations most commonly approached for extramural support. Corporate foundations are company sponsored, but are legally separate from them. Their funding activity is usually focused on research and education in areas related to the company’s interests and to geographic areas in which the company has operations.

Operating Foundations. Operating foundations are private foundations structured to fund their own intramural research, and are commonly found in the biomedical and pharmaceutical industries.

Community Foundations. Community foundations are created to serve regional interests and priorities. This type of public entity receives its funds from a variety of donors, much like the independent foundations, and may support a broad range of research. However, distribution of funds extramurally is highly restricted to the region in which the foundation operates.

Much like the state of the geopolitical world today, in which countries come and go, sponsors—whether they are governmental or nongovernmental—form and disperse, separate and integrate. New ones appear each year, some may merge permanently with others or combine resources temporarily for specific programs, and some may run out of money. For example, the NIH established an Institute for Alternative Medicine in the early 1990s; NSF and the Whitaker Foundation joined together in 1994 to support a research initiative on cost-effective health care technology. In parallel with these new initiatives, the federal Office of Technology Licensing, for example, was abolished and the U.S. superconducting collider project was terminated. Therefore, knowing which sponsors are in a formative or sunset phase, and which sponsors have funds to disperse or none remaining, can be valuable data points in finding a funding match.

Accessing Information About Sponsors

Information about sponsors’ standing interests and regional giving priorities can be obtained through their regular publications, annual reports, and home pages on the Internet. The Foundation Center Directory and associated publications also provide comprehensive summaries of sponsors spanning all disciplines (http://www.fdncenter.org). The American Psychological Association (APA) publishes a compendium of funding sources specifically for the brain and behavioral sciences (Herring, 1994).

Many sponsors also have changing priorities that appear in the form of special announcements, program announcements, or as requests for applications (RFAs) and requests for proposals (RFPs).

Special announcements, program announcements, and RFAs alert the scientific community about a new or renewed interest of a sponsor in a priority or expanding area. These opportunities can have an extended life span, and proposals may be submitted for any published deadline until the opportunity is withdrawn. The availability of funds, however, is not a precondition to their release.

By contrast, RFPs signify the specific availability of funds either for a grant or for a contract in a well-defined research area. Availability of RFP funding for a grant, per se, implies that a sponsor is seeking to fund research in a specific area, with the approach to the research proposed by the applicant. Contract funding, however, is typically for research with goals and deliverables explicitly directed by the sponsor. The applicant must be responsive to the contract terms with a time line for work and budget that conforms to the sponsor’s specific criteria. The impending release of an RFP is usually announced 3 to 4 months in advance of its publication. Once the RFP is released the required time to respond may be as short as 45 to 90 days and, unlike RFAs, it is usually a one-time solicitation.

Both RFAs and RFPs specify the type of funding mechanisms that may be used. The most common mechanisms across sponsors—both governmental and nongovernmental—are project-based research grants, multicomponent research program grants, career development grants, and small business grants. These are the focus of chapters 2 through 5. Other less frequently utilized mechanisms, such as construction and instrumentation grants, are also discussed in chapter 3 on multicomponent programs.

Institutional-sponsored projects and research development offices learn about these special funding opportunities through regular hard copy and electronic announcements. These come from sponsors locally, nationally (like NIH), and internationally, and are now accessible to every individual who has access to the World Wide Web. The Web has also provided access to funding information through sites maintained by professional societies such as the American Psychological Association (http://www.apa.org/science/fbinfo.html), the American Academy of Neurology (http://www.aan.com/public_res/publicfunding.html), the Society for Neuroscience (http://www.sfn.org/agency), and the Radiological Society of North America (http://www.rsna.org) (see also Bergan, 1996, for tips on electronically accessing sponsor information).

Many services also exist as central distributors of funding information. Some services, such as the Medical Research Funding Bulletin (Science Support Center, New York) and the ARIS Funding Reports (

http://www.arisnet.com), have subscription charges. A new Community of Science, Inc. service is designed to meet the information needs of research and development researchers worldwide, and is also a subscription-based resource (

http://medoc.gdb.org/repos/fund). Others, such as the FEDIX (

[email protected]) e-mail information service, are free of charge. FEDIX electronically distributes information about government research and educational funding opportunities at no charge to FEDIX subscribers. Distribution is made on the basis of a match between key words provided by the subscriber and participating agencies. Participating agencies include the Department of Energy, Federal Aviation Administration, NASA, Office of Naval Research, Air Force Office of Research, National Science Foundation, NIH, and the Department of Education. Distribution is daily.

New funding information sources are appearing routinely in the age of rapid electronic information dissemination; at the time of this writing, one of the latest and most promising one-stop shopping services specifically for training and early faculty development is Grantsnet (http://www.grantsnet.org), sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

It is not uncommon to subscribe to multiple sources of funding information. Although there is a fair amount of redundancy between the services, with as much as 25% to 30% new information in each, the time invested in proactively perusing them is worthwhile.

Funding Power, Paylines, and Award Rates

Funding power is the level at which a sponsor will fund proposals and, even with the most well-managed assets, it would be exceptional that a sponsor could fund every proposal submitted to it. Therefore, although scientific review determines which proposals are meritorious, a payline determines which proposals can actually be funded from that group. Paylines are the funding cutoffs defined either as an absolute score (e.g., a score on a scale of 1 to 100) or as relative score (e.g., percentile) or rank (e.g., 6th of 92 proposals) that indicate the position of a proposal with respect to other proposals reviewed in that cycle or over a set of cycles (the advantage of averaging over a series of cycles is that it tends to correct for some inevitable variability that exists between reviewers and review groups).

Sponsor paylines may be set a priori, as in the case when a sponsor funds only, for example, ten proposals in any cycle regardless of cost or number of proposals received, or may be set on the basis of the trade-off between available funds and the total cost of the most meritorious proposals. Although the latter is the norm, ...