This is a test

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

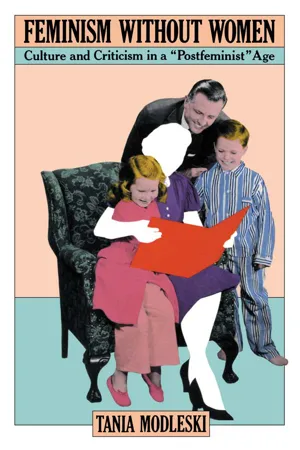

In a series of essays scrutinizing feminist and post-structuralists positions, Tania Modleski examines "the myth of postfeminism" and its operation in popular culture, especially popular film and cultural studies. (First published in 1991.)

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Feminism Without Women by Tania Modleski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Theory and Methodology

CHAPTER ONE

Postmortem on Postfeminism

In 1987, the New York Times Magazine published an article entitled “Literary Feminism Comes of Age.” The article begins with a vignette of the feminist critic Elaine Showalter teaching a course at Princeton University on the literature of the fin de siècle. The female author of the article quotes Showalter’s remarks about the “lunatic fringe of radical feminism” at the turn of the century. Some of these women, Showalter points out to the class, “labelled sperm a ‘virulent poison’ and advocated sexual abstinence as a political goal.”1 After offering this example of feminist lunacy from another era, the author immediately turns to a male critic, Peter Brooks, for an assessment of the present state of feminist criticism. (Although feminism is no longer in its minority it still seems to need a male authority figure to speak on its behalf and certify its legitimacy as well as its sanity.) Brooks, whose previous book on narrative theory contains only a single sentence about feminist criticism,2 remarks, “Anyone worth his [!] salt in literary criticism today has to become something of a feminist” (p. 110). And he goes on to assert, “The profession is becoming feminized” (p. 112). Yet the male critic’s confusion here, of feminism with feminization, may belie the author’s major claim—that feminist criticism in becoming absorbed into the academy has lost its ability to threaten the male literary establishment.

The article is in fact a perfect example of the kind of texts I will be discussing in much of this book—texts that, in proclaiming or assuming the advent of postfeminism, are actually engaged in negating the critiques and undermining the goals of feminism—in effect, delivering us back into a prefeminist world. Thus the Times author, in tacit defiance of feminism’s critique of the institution of the family, consistently adopts familial metaphors, domesticating women and putting them back in their “proper” sphere: “For feminist literary criticism,” she writes, “once a sort of illicit half sister in the academic world, has assumed a respectable place in the family order” (p. 110). Later she remarks, “Despite its growing respectability, feminist criticism retains a hint of scandal, like an old aunt who breaks into bawdy stories over tea” (p. 116). By the end of the article, then, literary feminism has not only come of age, but passed its prime and entered its dotage. And in the process the lunacy invoked at the beginning of the article reemerges as harmless senility.

The very format of the Times article belies the claim made in its title, especially when one remembers that not long before this piece appeared, the Times Magazine had run an elaborate spread on members of the Yale School of Criticism. Five or six full-page color photos of very important looking, prosperous, and, of course, male critics, most nearing retirement age (old uncles?), accompanied the article, which treated the subject of deconstruction with much fanfare. In contrast, the “Literary Feminism” article is illustrated by a single half-page black and white photo of “Princeton’s Elaine Showalter in her study.” Literary feminists may indeed have been accepted into the “family order,” but for all that they would seem to be rather poor relations.

GYNOCIDAL FEMINISMS

The decision to feature Elaine Showalter in the Times article is intriguing in light of this critic’s career trajectory, which is paradigmatic of the developments in feminist criticism that have motivated the writing of this book. Showalter, it may be remembered, was one of the most emphatic and articulate advocates of a female-oriented criticism she labeled “gynocritics.” By “gynocritics,” Showalter meant a kind of criticism that would move away from an “angry or loving fixation on male literature” and on “male models and theories” and would develop “new models based on the study of female experience.”3 For Showalter, feminist criticism found “its most challenging, inspiriting, and appropriate tasks” in concentrating on “female culture”—female literature, female “theory,” etc. (p. 135). To be sure, many found Showalter’s program to be too prescriptive, and ultimately untenable, since patriarchal texts clearly comprise a large part of “female experience”—which is not to say that the experience is identical to that of men. (Thus, for example, my own work on the films of Alfred Hitchcock was motivated by the desire to understand this very misogynist director’s popularity with female viewers.) Nevertheless, Showalter’s strong defense of women and women’s experience, combined with her forceful critiques of male critics who seemed to be coopting feminism and rendering women silent and invisible, were inspiring to those feminist critics struggling to theorize a viable and theoretically sophisticated notion of the female as social subject at a period when the very idea of the subject was undergoing a series of philosophical challenges.

Then, soon after the “Literary Feminism” article appeared, Showalter shifted her focus to “gender studies,” and in 1989 published an edited volume entitled Speaking of Gender. In her introduction, Showalter an-nounces feminism’s departure from the “gynocritics” of the 1970s and early 1980s, argues for the necessity of considering questions of masculinity, and heralds a “renewed feminist interest in reading male texts, not as documents of sexism and misogyny, but as inscriptions of gender and ‘renditions of sexual difference.’ ”4 While Showalter is aware of the danger of cooptation on the part of male critics and understands the feminist concern that male critics might “appropriate, penetrate or exploit feminist discourse for professional advantage” (p. 7), she clearly approves of the direction taken by a generation of younger male critics focusing on masculinity as a construct rather than “a universal norm” (p. 8). Most disturbing about this introduction, however, is its marginalization of feminism in the sense that Showalter is no longer focused on the question (which is the question of the present volume): what’s in these new developments for feminism and for women? Showalter writes, “While men’s studies, gay studies, and feminist criticism have different politics and priorities, together they are moving beyond ‘male feminism’ to raise challenging questions about masculinity in literary texts, questions that enable gender criticism to develop” (p. 8). Feminism, in this formulation, is a conduit to the more comprehensive field of gender studies; no longer is the latter judged, as in my opinion it ought to be, according to the contributions it can make to the feminist project and the aid it can give us in illuminating the causes, effects, scope, and limits of male dominance.

Showalter certainly seems to be accurate in assessing gender studies to be a new phase (although it might prove yet to be the phase-out) of feminist studies. Her book takes a place alongside, for example, journals with names like Genders and Differences, titles that stand in marked contrast to those of journals created in the 1970s like Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society and Feminist Studies. An even more telling sign of the times, however, has been the advent in the 1980s of a new form of anthology organized around debates between men and women who read one another’s texts and take each other to task for their positions on a whole array of issues relating to male feminism and sexual difference. (The first and most notorious of these is Men in Feminism which I discuss in Chapter 4).5 While these books, in staging the perennially fascinating “battle of the sexes,” make for very compelling reading, they can be considered “postfeminist” in several respects. First, insofar as they focus on the question of male feminism as a “topic” for men and women to engage (as the first one did), these books are bringing men back to center stage and diverting feminists from tasks more pressing than deciding about the appropriateness of the label “feminist” for men. Second, the books in their very format betray a kind of heterosexual presumption—a presumption pointed out by the gay male critic Lee Edelman, who in one of these books speaks on behalf of the absent lesbian (and we should note in passing that the practice of including an inoculating critique of its own blind spots, so as to allow business to proceed as usual, has become a common tactic in contemporary political criticism).6 Third, the anthologies tacitly assume and promote a liberal notion of the formal equality of men and women, whose viewpoints are structurally accorded equal weight. Thus while terms like “dialogism” (drawn from the work of Mikhail Bakhtin) are commonly invoked in the rationale for these volumes, it is hard to see how such a term functions as anything other than a euphemism for “dialogue”—a concept that in eliding the question of power asymmetry has rather conservative implications.7

Collections like these have drawn a great deal of notice and publicity, but the kind of work most useful to feminism has, in my opinion, been the work men are doing without clamoring for women’s attention and approval. As Paul Smith, who is given the last word in the Times article, is quoted as saying: “My feeling is that men should be kind of quietly doing the things that support feminism, without at this point being able to get any credit for that” (p. 117).

But a little credit where credit is due. A body of male criticism supportive of the feminist project is beginning to develop, and the criticism I have personally found most useful in thinking through my own subject is the kind that analyzes male power, male hegemony, with a concern for the effects of this power on the female subject and with an awareness of how frequently male subjectivity works to appropriate “femininity” while oppressing women. This male feminist criticism reveals such appropriations, which I will be investigating in this book, to be deeply embedded in the American cultural tradition. Thus, in an extremely interesting essay entitled “The Politics of Male Suffering: Masochism and Hegemony in the American Renaissance,” Christopher Newfield examines Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter to show how the character of Arthur Dimmesdale undergoes an exemplary process of “male feminization” that is empowering to men and disempowering to women. “Hegemonic patriarchy can survive,” Newfield argues,

without male assertion, but not without feminization: only feminization enables men to evade the one-directional dominations of stereotypical masculinity, to master the non-conflictual, and to occupy both sides of a question. Whereas tyranny depends on male supremacy, liberal hegemony or “consensus” depends on male femininity.8

These insights confirm my own conviction that however much male subjectivity may currently be “in crisis,” as certain optimistic feminists are now declaring, we need to consider the extent to which male power is actually consolidated through cycles of crisis and resolution, whereby men ultimately deal with the threat of female power by incorporating it. Such a process will become clearer in later chapters, where I discuss Three Men and a Baby, the phenomenon of Pee-wee Herman, and current theorizations of male masochism, but I wish to give some indication here of how the process works in recent writing by established male theorists and critics.

To begin, we might, for purposes of comparison, consider the following quotation from the work of another critic of American culture, David Leverenz, whose work, like Newfield’s, shows a real concern for and knowledge about how male power frequently works to efface female subjectivity by occupying the site of femininity. In an analysis of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Leverenz challenges the tendency within criticism to label Emerson’s power “female,” and he notes the way in which a certain conceptualization of femininity as an attribute of the mind operated in Emersonian thought at the expense of women:

Though Emerson challenges the social definitions of manhood and power, he does not question the more fundamental code that binds manhood and power together at the expense of intimacy. Emerson’s ideal of manly self-empowering reduces womanhood to spiritual nurturance while erasing female subjectivity. “Self-Reliance” takes for granted the presence of faceless mothering in the mind, an ideal state of mental health that he sums up in a memorable image: “The nonchalance of boys who are sure of a dinner.”9

To understand how a male feminist approach like Leverenz’s differs from “postfeminist” male appropriations of feminism, I would like to contrast this passage to one from Stanley Cavell, taken from his analysis of the 1937 film Stella Dallas, which forms part of a larger work on “melodramas of unknown women.” In this new project, Cavell analyzes a genre, melodrama (a.k.a. the woman’s film), which has been important in feminist film theory because, as “texts of muteness,” melodramas seem to strive to articulate a voice repressed within patriarchal culture. Women are attracted to the genre, it has been suggested, because melodrama is about the drive for total expression and for recognition of that which in women’s lives and feelings has been misrecognized, misunderstood, and repressed.10 But Cavell, in focusing on melodramas of the 1930s and 1940s, appears, like many other conservative thinkers at the present time, to be attempting to contain the threat posed by feminist thought and to reposition the struggle between feminism and the patriarchal tradition as a struggle inhering in that tradition. This, in turn, involves a remystification of precisely the mode of thought analyzed by Leverenz, and it reveals a confusion between feminism and feminization similar to the one we saw in the quotation from Brooks at the outset. In the following passage Cavell, who has indicated that his analysis of Stella Dallas is meant to “preserve” philosophy as he knows it, tries to rescue the “feminine” Emersonian tradition from “male philosophy” and in the process to make common cause with feminist critics:

I have written as though the woman’s demand for a voice, for a language, for attention to, and the power to enforce attention to, her own subjectivity, say to her difference of existence, is expressible as a response to an Emersonian demand for thinking. I suppose that what for me authorizes this supposition is my interpretation of Emerson’s authorship as itself responding to his sense of the right to such a demand as already voiced on the feminine side, requiring a sense of thinking as a reception …, and as a bearing of pain, which masculine philosophy would avoid.11

We will put aside the dubious reliance on stereotypes of femininity as passive and masochistic to look at the way Cavell’s text enacts what Leverenz’s deconstructs. In Cavell, female subjectivity and feminism itself are assimilated to the “feminine” mind of a male philosopher—and we might note that the “faceless mothering” of the mind referred to by Leverenz is an especially apt term given Cavell’s use of the text Stella Dallas, the archetypal story of a mother’s self-effacing sacrifice of her child for the child’s own social advancement. Cavell is canny enough to suspect himself of negating the voice he is claiming to help bring forth, for he asks, “Does this idea of the feminine philosophical demand serve to prefigure, or does it serve ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: Theory and Methodology

- Part II: Masculinity and Male Feminism

- Part III: Race, Gender, and Sexuality

- Notes

- Index of Films

- Index