![]()

I

Introduction

![]()

1

Ecological Psychology Theory: Historical Overview and Application to Educational Ecosystems

Jody L. Swartz

Northern Arizona University

University of Wisconsin-Superior

William E. Martin, Jr.

Northern Arizona University

The conception that an individual’s developmental and adaptational processes are influenced by his or her interaction with the environment has long been discussed in the psychological and educational literature. Although there is an abundance of theoretical applications and research supporting this concept, the predominant trend has been to emphasize the properties of the person. As a result, one is left to assume that the genesis of difficulties in adaptation lies in internal or personal states and traits of the individual. According to Bronfenbrenner (1979), “There has been a hypertrophy of research focusing on the properties of the person and only the most rudimentary conception and characterization of the environment in which the person is found” (p. 16). Although the growth of the field of ecological psychology is evidenced by an increase in research, there still exists little information on how to conceptualize concerns and apply interventions from an ecological perspective (Hewett, 1987; Johnson, Johnson, & DeMatta, 1991). Indeed, it continues to be true that “It... is not much clearer how one creates an ecological classroom, an ecological curriculum, or trains an ecological teacher” (Hewett, 1987, p. 62).

The importance of using an ecological approach to understanding and effecting positive change for problems in ecosystems such as schools and communities must be underscored, particularly when considering the multiple and multifaceted environments in which the individual functions. Communities, the families and schools located within them, and the individuals comprising these systems are integral parts of ecological networks. Consequently, positive intervention outcomes rely on understanding these networks. This is particularly true for school-aged youth who are influenced not only by the school, family, peer, and community systems in which they function, but also by the complex interrelationships among these systems (Christenson, 1993; Hobbs, 1966). However, this is an often difficult and cumbersome task for educators, parents, and school systems to undertake (Hendrickson, Gable, & Shores, 1987). To this end, the following eight chapters provide a brief review of the foundations of ecological psychology and focus on the functional application of ecological psychology for schools within communities. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of the development and current status of ecological psychology, we discuss the theoretical undergirdings of ecological psychology, review past research using the ecological approach, and suggest the role and function of an applied ecological approach to working with individuals who experience difficulties in adaptation in their schools and, consequently, lack “fit” with their environment.

Philosophical Underpinnings of Ecological Psychology

Collectively, ecological psychology theories endeavor to compensate for the paucity of research on the characteristics and impact of the environment (Johnson, Swartz, & Martin, 1995). Ecological psychology theories, in the broadest sense, strive to explain the natural patterns of stimuli, both social and physical, which exist in the individual’s immediate environment and subsequently impact the individual’s behavior and experience (LeCompte, 1972). When considering that the relationship between the individual and the environment is continuous, reciprocal, and interdependent (Bijou & Baer, 1978; Evans, Gable, & Evans, 1993), it is clear that as individuals and environments interact, new stimuli emerge that require constant adaptation for both the individual and the environment to maintain a balance, or a good match. As such, ecological approaches are concerned with how to optimize this adaptation process and, in doing so, examine both the match and/or mismatch between an individual and the reciprocal nature of the person-environment association (Conoley & Haynes, 1992; Fine, 1985).

When an individual experiences difficulties in adaptation, it is explained in terms of the lack of fit between the existing properties of the individual and the environment—a discordance in the system (Hewett, 1987). It is important to keep in mind, however, that this discordance is sometimes specific to certain settings and the variables within those settings rather than pervasive behavioral deficits seen across settings (Evans et al., 1993; Hendrickson et al., 1987). Regardless of whether the difficulties are situation specific or cross-situational, an ecological understanding of the student is of paramount importance. For students, who are at the same time participants and observers in several distinct and overlapping settings, it is essential to explore this person-environment interaction. More specifically, to adequately understand individuals requires the simultaneous examination of both the situational influences and the adaptive processes employed by individuals to select and create environments (Moos, 1980; Smead, 1982) and then to work with the knowledge gained to help individuals and their environment achieve a successful adaptation or adjustment process.

Development of Ecological Psychology as an Applied Psychology

When reviewing the development of applied ecological psychology, one limitation lies in its sometimes confusing and complex theoretical history. Perhaps it is this confusion that has led some educational researchers, such as Hilton (1987), to presume that an ecological orientation is not grounded in theory. Contrary to this supposition, ecological psychology has a long history tracing back to the early 1900s. In 1909, counseling psychologist Frank Parsons1 proposed that satisfaction can be achieved through knowledge of both individuals and environments, not merely one or the other. This premise of person–environment psychology was later expanded in the interactionist framework under which ecological psychology is subsumed. Specifically, as early as 1924, Kantor suggested that, as the person is a function of the environment and the environment is a function of the person, the unit of study in psychology should be the individual as that individual interacts with the contexts which produce behavior. In other words, behavior is a function of the interaction between the person and the environment, B = f (P, E). A decade later, Koffka (1935), a gestalt psychologist, further delineated the environmental components of the interactionist model into the geographical environment that is shared by individuals (i.e., all individuals in a classroom are in the same geographical environment) and the behavioral (psychological) environment that is a result of the interaction between the geographical environment and the individual (i.e., how an individual perceives the geographical environment). According to Koffka’s framework, understanding an individual’s behavior cannot be gleaned from examining either the person or the environment in isolation, but is dependent upon simultaneous consideration of both.

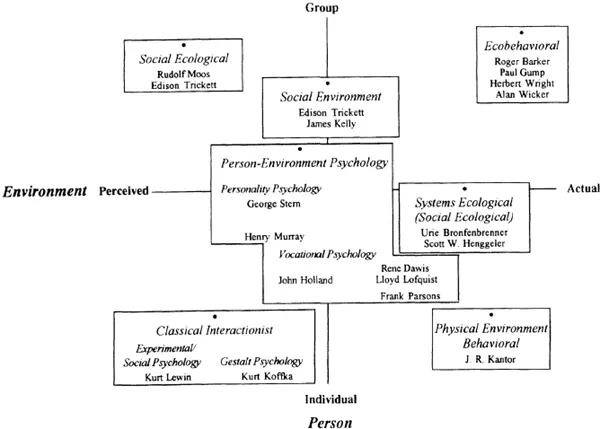

Although the roots of the ecological model appear to have a long history (see Ekehammer, 1974; Schmid, 1987; Walsh & Betz, 1995), it was not until the 1930s that ecological psychology as a separate domain began to emerge through the work of Kurt Lewin (1935, 1951) and later Roger Barker and his colleagues (Barker, 1965, 1968, 1978; Barker & Gump, 1964; Barker & Schoggen, 1973; Barker & Wright, 1954; Gump, 1975; Wicker, 1973, 1983, 1992). Through these and other theorists, the primary assumption undergirding ecological psychology emerged: Behavior is a function of the person and the environment, and the unit of study is the natural environment. Although the underlying premise of ecological psychology retained its original intent, theorists approached the ecological “problem” from different perspectives, placed along a continuum from a focus on the more subjective or the psychological features of the environment to the more objective or the social and physical features of the environment. According to Allport (cited in Fuhrer, 1990), this difference is referred to as the inside–outside problem or the ecological–psychological gap between the actual and perceived environment. Within this gap, and similarly important, is that different theorists and researchers tend to organize their definitions and constructs according to individual or group explanatory models, that is, whether the unit of study should be the individual or the group. Taken together, the actual environment versus perceived environment and the individual versus the group, both historical and contemporary psychologists who have impacted our understanding of the person–environment relationships can be conceived of as conceptualizing behavior in terms of an integration of the following four dimensions: perceived environment, actual environment, individual, and group. Figure 1.1 presents a two-dimensional graphic depicting this relationship between the historical and contemporary theorists and researchers in ecological psychology.

Fig. 1.1. Matrix of influential ecological psychology theorists by subspecialty.

Actual or Perceived? Individual or Group?

Historical Theorists

B = f(Perceived[Environment] × Individual[Person]). Theorists more interested in the psychological features of the environment, such as Lewin (1935, 1951), emphasized the people’s phenomenological experience of their environmental situation in understanding individuals. Although Lewin is considered an ecological psychologist and an experimental social psychologist, his training and primary orientation in gestalt psychology is evident in his emphasis on consideration of the whole situation rather than either the person or the environment piecemeal. Lewin (1935) posited that behavior is a function of the whole environment, including the mutually dependent interaction between the person and the environment, from which individuals generate subjective observations about the environment, themselves, and their behavior. Lewin termed this psychological environment the life space, which is defined as all aspects of individuals and their subjective environments that impact behavior. According to Lewin, the life space is interdependent with the nonpsychological (objective) environment. Although Lewin accepted that the nonpsychological environment impacts behavior, his focus remained primarily on the psychological environment. Specifically, he maintained that individuals’ behavioral environments are the result of their subjective experience of the objective physical environment. any given time and that it is this experience that generates patterns of action and subsequently interaction between the individual and the environment. Changes in behavior, then, rely on modifications in how the individual perceives the environment.

B = f(Actual[Environment] × Group[Person]). On the other end of the continuum are those researchers, such as Barker and his colleagues (Barker, 1965,1968,1978; Barker & Gump, 1964; Barker & Schoggen, 1973; Barker & Wright, 1954; Gump, 1975; Wicker, 1973,1983,1992), who focused their attention on the more objective characteristics of the environment. Although Barker (1968) concurred with Lewin’s assertion that people’s momentary behavior is determined by their life space, he further stated that “if we wish to understand more than the immediate ... behavior, ... knowledge of the ecological environment is essential ... Development is not a momentary phenomenon, and the course of the life space can only be known within the ecological environment in which it is embedded” (p. 9). According to Barker (1968), because a person’s behavior changes from setting to setting, and individuals within a setting tend to behave in a similar manner, it is not necessarily the people in the settings, but the setting itself, that is the unit of study. Accordingly, Barker posited that the focus of analysis should be on the functioning environment or nonpsychological environment that is comprised of multiple behavior settings or small ecosystems that call forth particular behavior. Behavior settings are persistent patterns of behavior that occur within a specific period of time and in a specific place (Carlson, Scott, & Eklund, 1980; Wicker, 1983). In addition to physical attributes (e.g., arrangement of furniture, size, accessories), behavior settings have social characteristics such as rules and norms that dictate a routinized pattern of action carried out by the people inhabiting the setting (Wandersman, Murday, & Wadsworth, 1979). Thus, it is the setting itself, rather than the person’s perception of the setting, that calls forth certain types of behavior from the individuals who inhabit them (Barker, 1968; Trickett & Moos, 1974) such that, when in school, students “behave school” and, when at home, they “behave home.” Despite his obvious partiality toward the environment, Barker did concede that an individual’s satisfaction with the environment and goals within the environment will affect the degree to which the rules of the setting influence the individual’s behavior (Walsh & Betz, 1995). Barker’s student, Alan Wicker, explored this area more fully in his work on cause maps and major life pursuits (see Wicker, 1992).2

Although the approaches come from different foci, both delineate a means of understanding how environments determine an individual’s adaptation or adjustment (Wandersman et al., 1979). Specifically, when individuals either adapt or adjust their behavior, they are striving to retain concordance (or fit) with their environment. In this manner, understanding the individual’s interdependent relationship with the environment draws on delineating both how the individual is impacted by changes in the environment (e.g., changes in norms or rules; Barker, 1968) and how the environment is impacted by changes in the individual (e.g., shifts in perception; Lewin, 1951). Consequently, this interplay between individuals and their environment is a continuous process whereby individuals seek to maintain homeostasis within their system and subsystems.

Contemporary Ecological Psychology

Drawing upon the notion of the importance of the individual’s perception of the environment (Lewin, 1951) and the necessity of understanding the environment to discern the individual’s pattern of behavior (Barker, 1968), are logical outgrowths of Lewin’s and Barker’s work in ecological psychology. Although contemporary interactionists are aligned with different fields of psychology, their work continues to fall under the auspices of ecological psychology and integrates the four dimensions of ecological psychology mentioned previously. Discussed here are the social environment researchers such as Kelly and his colleagues (Kelly, 1967, 1970, 1971, 1979, 1986; Trickett, Kelly, & Todd, 1972; Trickett, Kelly, & Vincent, 1985; Trickett & Todd, 1972; Watts, 1992), Moos and his colleagues (Moos, 1970, 1976; Trickett & Moos, 1973,1974), and the systems ecological perspective (SEP) researchers (Fine, 1985, 1990, 1995; Henggeler & Borduin, 1990; Henggeler, Schoenwald, & Pickrel, 1995; Schoenwald, Henggeler, Pickrel, & Cunningham, 1996) most closely aligned to the work of Bronfenbrenner in his social ecological and person–process–context–time model (1979, 1980,1986, 1995).

B = f(Perceived[Environment] × Group[Person]). Like Barker, Moos and his colleagues (Moos, 1970,1976; Moos & Trickett, 1987; Trickett & Moos, 1973, 1974) focused their work on delineatin...