eBook - ePub

Computational and Clinical Approaches to Pattern Recognition and Concept Formation

Quantitative Analyses of Behavior, Volume IX

This is a test

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Computational and Clinical Approaches to Pattern Recognition and Concept Formation

Quantitative Analyses of Behavior, Volume IX

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The ninth volume in this highly acclaimed series discusses the computational and clinical approaches to pattern recognition and concept formation regarding: visual and spatial processing models; computational models, templates and hierarchical models. An ideal reference for students and professionals in experimental psychology and behavioral analysis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Computational and Clinical Approaches to Pattern Recognition and Concept Formation by Michael L. Commons,Richard J. Herrnstein,Stephen M. Kosslyn,David B. Mumford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I | VISUAL- AND SPATIAL-PROCESSING MODELS |

1 | Mechanisms of Production Control and Belief Fixation in Human Visuospatial Processing: Clinical Evidence from Unilateral Neglect and Misrepresentation |

INTRODUCTION

The Modularity of Perceptual and Representational Processes

Goal-directed, adaptive behavior requires, among other things, discriminative monitoring of activity originating from without (perception), as contrasted to activity originating from within the system itself (representation).

A certain amount of perceptual processing is carried out by relatively autonomous, domain-specific subsystems, which, though exploiting previously acquired knowledge (cf. the Helmholtzian notion of “unconscious inference” in Dodwell, 1975, p. 60), cannot be molded at will by top-down (i.e., cognitive) influences. As Fodor (1983) has pointed out, one cannot deliberately hear a speech as a noise or see the two shafts of the Mueller-Lyer illusory patterns as being of equal length, even if one knows they are such. In other words, perceptual processing is held to be, to some extent, modular.

It has been suggested that the anatomical structures subserving perception might also be involved in representational activity (Merzenich & Kaas, 1980). Evidence has also been given—e.g., through experiments requiring mental rotation of patterns (Shepard & Metzler, 1971) or scanning of mental images (Kosslyn, 1980)—that perception and representation share functional properties of analogue (as opposed to propositional) correspondence to perceived or represented objects. Furthermore, patients with circumscribed brain lesions may not only have circumscribed sensory defects; they may also suffer from circumscribed representational lacunae of which they are quite unaware (Bisiach, Capitani, Luzzatti, & Perani, 1981; Bisiach, Luzzatti, & Perani, 1979). The cognitively uncontrollable shaping of hallucinations and hypnagogic images constitutes additional evidence for the quasiperceptual properties of some kinds of representational activity (Hebb, 1968; Shepard, 1984). On these grounds, it is reasonable to admit that representation itself is largely modular in the same sense as perception.

The question of modularity becomes more subtle if related to more abstract thought processes. According to Fodor (1983), the core of the cognitive machinery does not show the modularity of its tributary, stimulus-driven input systems. It has no domain-specific ordering and is isotropic insofar as at that level each process has a potential for reciprocal interaction with any other process. This claim, according to Fodor (1983, p. 101), holds for the cognitive center of the system “in important respects.” The phrase is well chosen because there might be equally important respects in which vestiges of modularity are preserved in thought processes, so that more or less segregated streams of activity might even be discerned beyond the level of sensory transducers and input analyzers. Clinical neurology may indeed afford some means for tracking modularity beyond the initial stages of information processing, i.e., for showing that cognitive processing is not a homogeneous cloud of wholly interconnected activities but may itself have a modular (or quasimodular) structure.

Anosognosia

One hundred years ago, von Monakov (1885) published the first known report of blindness resulting from circumscribed brain lesion without the patient's being aware of the severe sensory defect. Von Monakov, by contrasting his case to cases in which similar disorders appear following diffuse brain damage and might therefore be ascribed to general intellectual impairment, hinted at the dissociability of the cognitive disfunction.

The selective impairment of thought processes in patients affected by blindness from focal brain lesions was also remarked on by subsequent researchers such as Anton (1899) and Barat (1912). Since then, many cases of “cortical” blindness have been described. They fall into one of the following four types (Nobile & D'Agata, 1951): (1) The patient does not deny his blindness outright but never mentions it spontaneously and seems quite unconcerned by it; (2) the patient denies blindness and claims that he cannot see for other reasons (e.g., darkness due to the light being turned off); (3) the denial of blindness is associated with lucid descriptions of what the patient maintains that he sees. The content of his visual experiences is of a plausible kind and often has some connection to real events in his past life; (4) the denial of blindness appears against a background of general confusion and mental deterioration. Visual hallucinations seem to be independent of the stream of thought, which, on the contrary, they influence.

Throughout the whole history of investigation of anosognosia (i.e., un-awareness-denial of an illness resulting from brain lesion), however, a still unresolved controversy is evident between two rival conceptions of the phenomenon. According to the first, denial of illness and pathological sensory-like productions are the consequence of a more general disorder of thought. The second conception emphasizes the domain-specific character of cognitive disorders. Intuitively, the first view might seem to be promptly falsified by instances in which the cognitive disorders are segregated to such an extent that, as in the famous case published by Anton (1899), a patient obdurately disclaiming her blindness may nonetheless be fully (and painfully) cognizant of a far less disabling mild dysphasia. Furthermore, Angelergues, de Ajuriaguerra, and Hécaen (1960) have made a point of the fact that there are instances in which severe mental deterioration does not entail anosognosia. Unfortunately, however, there is at our disposal no safe criterion on which to decide whether a thought disorder is genuinely domain specific. Indeed, even admitting a relative modularity of thought processes, nobody would deny that such processes are also, in important respects, isotropic in Fodor's sense—that is, subjected, at the very least, to some degree of intermodular leakage. So, one way out of the dilemma that seems to bedevil the study of anosognosia might be the admission that both views are wrong—wrong, that is, if uncompromisingly held in their extreme formulations.

Given these premises, it is practically convenient to sketch a purposedly tendentious model of cognitive processing inspired by the (more inciting) second position, which sees anosognosia and related phenomena as, at least in some instances, modality-specific disorders of thought. The model, compatible with known clinical data, might thus be confronted with (and possibly refuted or ameliorated by) further findings from anecdotal or systematic neuropsychological observations.

A Model of Cognitive Processing

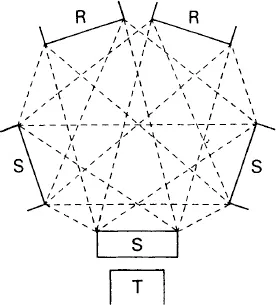

Although ambitious, the model may be initially very simple (Fig. 1.1). One may start from the fact that visual defects due to lesions of the nervous system are subject to a first dichotomy. There are peripheral lesions that produce absolute blindness, in the sense that no residual impulse from the retina reaches the centers in which cognitive processes are assumed to take place. The whole behavior being consistent with blindness, the patient admits the presence of the sensory defect and no belief of reality is fixed to possible visual representations. On the other hand, there are more central lesions of the visual system that also seem to prevent any cognitive processing of visual input. These, however, are associated with a visuospecific cognitive dysfunction that manifests itself in a disordered monitoring of the disability (such that the patient denies blindness or behaves as if pretending to see) and in visual experiences that the patient purports to perceive from real objects.

By way of first approximation, one might suppose that the first type of disorder corresponds to the failure of the sensory transducer (T), whereas the second implies the breakdown of a sensory processor (S) intervening between the transducer and the (as yet unanalyzed) core system corresponding to thought processes. This rough subdivision leaves the transition between sensory transducer and intervening sensory processor largely unspecified and passes over details that would be crucial points at a level of finer grained analysis. To mention just one such instance, the phenomenon of blind-sight (Perenin & Jeannerod, 1975; Weiskrantz, Warrington, Sanders, & Marshall, 1974) is not considered here.

FIG. 1.1. A model of cognitive processing based on the assumption that anosognosia and related phenomena are modality-specific disorders of thought.

The boldest feature of the model consists in the suggestion that messages issued from modality-specific sensory processors—involved in perceptual as well as in representational activity—and propagating over the neural net subserving thought processes are not simply tagged according to their source but flow along relatively segregated paths, interlaced to input from other sensory channels, towards the outlets of different response systems (R). This quasimodular structure of central processes, which imposes some limits on their isotropism, might explain the domain-specific quality of cognitive disorders corresponding to the different forms of anosognosia, as well as their rigidity, that is the usual tendency of patients suffering from those forms of anosognosia to unyieldingly withstand persuasion.

The occurrence of such domain-specific cognitive disorders that result from local failures of sensory processors suggests a decentralization and a specialization of the mechanisms for cognitive control (Bisiach, Vallar, Perani, Papagno, & Berti, 1986). Indeed, such disorders are incompatible with the idea of a superordinate, general-purpose module detecting and controlling failures in the system. As was argued elsewhere in a somewhat different context (Bisiach et al., 1979), a supreme autonomous control unit should of necessity be endowed with a model of its domain of intervention, a model that should, among other things, ensure monitoring of local disorders in such...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Volumes in the QUANTITATIVE ANALYSES OF BEHAVIOR series

- CONTENTS

- About the Editors

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- PART I VISUAL- AND SPATIAL-PROCESSING MODELS

- PART II COMPUTATIONAL MODELS

- PART III TEMPLATE AND HIERARCHICAL MODELS

- Author Index

- Subject Index