![]()

1 Religion

An institutional portrait

| • | Ancient movers: how religious beliefs and actors shaped history and how religion's roles have changed |

| • | Religion and state in contemporary societies |

| • | The “Islamic world” and “the West” |

| • | Clash of civilizations? |

| • | Contemporary religious dynamics |

| • | Blessed are the peacemakers |

| • | Religious demography and attitudes |

| • | Religion's organizational forms |

| • | Conclusion |

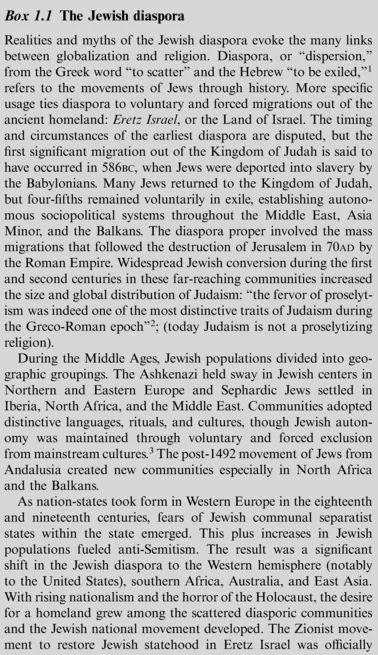

The world's many religious traditions have given rise to an extraordinary range of institutions. This chapter situates these institutions within an historical context and in the framework of contemporary global institutions. To do so, a reflection on historic visions and manifestations of religion is an essential first step. Religious leaders and organizations often paved the way for transnational movements of people and institutions: in that sense, they were the original globalizers. For much of world history, religion was so central to belief systems, governance, and notions of authority as to make the distinctions among them—distinctions that we still labor to draw today—largely inconceivable. The first part of the chapter thus focuses on four critical topics: the mid-seventeenth-century European move towards the ideal of a nation-state that distinguished religious and secular authority and the subsequent rise of "secular" norms; the United Nations (UN) Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its assertion of the right to religious freedom, suggesting both freedom to practice a religion and freedom from rule by religion; contemporary debates around the roles of religious beliefs, laws, and authority that in some instances pit a "Western" versus a "non-Western" world (and its particular links to the idea of a clash of civilizations); and an exploration of the "secularization" of international relations in the post-World War II era, then followed by the current revival of interest in religious institutions and roles. The chapter also introduces a discussion of religion as a factor in violence and war as well as peace and social cohesion (this is treated in greater detail in Chapter 5). While religion remains a significant source of conflict today—often indirectly, sometimes directly—religious peacemaking is also an important force. These contrasting dimensions of religion are central elements of the institutional landscape.

Religious demography is also an essential part of understanding contemporary religious institutions. Three clear trends are notable: the growing weight of non-European and non-North American religious communities within major religious traditions; the transnational patterns that religious fundamentalism and extremism are taking; and the growing complexity of plural societies, juxtaposed with greater concentrations of adherence to the major global religions. The religious transformations of the twentieth century represent perhaps one of that era's most significant social developments and the worlds of religion are still today undergoing profound transformations that are linked inter alia to modernization, migration, and the impact of technology and new modes of communication.

Against the backdrop of this dynamic portrait of changing religious demography, patterns of religious adherence, and organizations, this chapter sets out a framework to help guide the navigation among very different types of religious institutions.

Ancient movers: how religious beliefs and actors shaped history and how religion’s roles have changed

From the earliest recorded history religion and government were intertwined, and political authority was commonly associated with some mystical or spiritual force. This is still frequently the case in indigenous societies; in Africa, for example, many chiefs are seen as carrying a spiritual as well as a temporal role and authority. From the first millennium BCE, and especially after the middle of the first millennium ad, many religions, in an institutionalized form, took on vastly expanded roles as moral and political authorities and acquired significant worldly power and wealth. Government and religion were often de facto one and the same, with the authority that came from religion often trumping even power strongly based on military might. This was particularly the case for the Catholic Church and, after the seventh century, Islamic Caliphates, but there are parallels in other world religions and regions, notably China and Japan, Persia (under the Zoroastrians), and South Asia. Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), who represented an apex of Christian power, described the power relationships as a linking of day and night, sun and moon (with religious authority representing day and sun):

In the same way for the firmament of the universal Church, which is spoken of as heaven, he appointed two great dignitaries; the greater to bear rule over souls (these being, as it were, days), the lesser to bear rule over bodies (those being, as it were, nights). These dignitaries are the pontifical authority and the royal power. Furthermore, the moon derives her light from the sun, and is in truth inferior to the sun in both size and quality, in position as well as effect. In the same way the royal power derives its dignity from the pontifical authority: and the more closely it cleaves to the sphere of that authority the less is the light with which it is adorned; the further it is removed, the more it increases in splendour.1

Part of this concept of the integration of religion and government was that a single faith was seen as essential to civil order, and a vital element of the social fabric. Having the right faith was essential to pleasing God, who upheld the natural order and averted disaster. Religious heresy was treason, and religious toleration was seen as admitting evil and dangerous elements into society.

For over a millennium, the stories of civilizations were thus to a large degree narratives of the ebb and flow of religious and temporal power. Conquests, conversions, and defeat involved many different authorities, and their ties to religion were elemental. During Europe's Middle Ages, the ideal was that a universal Christian empire and a universal church would hold sway, harking back to ideals of the height of the Roman and Carolingian Empires. The reality, however, was often quite different: fractured feudal rule with deep political divisions among many principalities, free cities, duchies, and feudal kingdoms. However, for centuries there was a religious unity in the Christian world and little question that the Church was a primary political force and actor. These assumptions and ideals were shattered by the Protestant Reformation which in turn gave rise to centuries of warfare, fought often in the name of religion—an experience which to this day shapes the views of many who look with unease to the explosive potential of religious conflicts and perceived dangers of religious involvement in governance. Likewise, as Islamic soldiers and merchants swept across vast regions of the world beginning in the seventh century, there were again ideals of the Umma, the united community that combined spiritual and religious authority, but here also sharp schisms emerged, notably between Sunni and various forms of Shi'a Islam. For centuries the Ottoman Empire combined political and spiritual rule, with the noteworthy characteristic that multiple religious communities were an accepted part of the regime. However, it was succeeded by a fractured set of communities that dreamed of unity but rarely came close to achieving it.

Alongside the epic power struggles that dominated geopolitics, the religion in which people believed and which dictated the rhythm of lives and days was in large measure either an inherited identity, not open to question, or an identity and rule imposed as the religion practiced by the rulers. Religion was important, shaping worldviews, influencing land tenure, defining ideals of family and community, and affecting financial matters at all levels, but choosing one's religion was hardly the norm and dissenters and religious minorities were often subject to discrimination or persecution. The Latin phrase cuius regio, eius religio means that the religion of the King was the religion of those he governed. A term coined by jurists in the Holy Roman Empire, which occupied much of Central Europe, it implied that each prince in the empire could decide which tradition his subjects would follow. In England in the 17th century, the monarchy shifted from Catholic to Protestant, back to Catholic and finally — under Elizabeth the First —to Protestant. The result was violent persecution of those who did not follow suit. The discriminatory laws and persecution of Jews in Europe, especially during the Spanish Inquisition, were emblematic of an era in which religion and authority were largely one and the same, and where tolerance of diverse beliefs was far from the norm. One of history's most extraordinary stories is that of the global movement of the Jewish people as they fled persecution and exercised their remarkable talent for creative solutions to their environment (see Box 1.1). The motivation for the emigration of colonists to North America was driven in large measure by persecution of groups termed "non-conformists." The early years of settlement and history have both a dark side and one with visionary ideals and courageous application. The exclusivism that characterized much colonial enterprise, including in North America, resulted in the destruction of indigenous communities as the colonies that became the United States of America expanded. The contrasting courage of people who stood behind their beliefs and opened themselves to different traditions is equally part of the legacy. American concepts of religious freedom as they were hammered out in the United States Constitution were marked by this experience.

In reflections on the relationships between religious and political authority in the modern era, the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 is held up as a watershed. Its main goal and result was a peace agreement that recognized what has come to be known as the nation-state. It also broke the perceived and actual power hold of the church. Box 1.2 elaborates on some of the Westphalian principles and agreements. Westphalia, in effect, represented the end of the dream of a unified Christian Empire, yet in France the continuing influence of the ideal of une foi, une loi, un roi (one faith, one law, one king) was an indication that lingering assumptions and practical experience still reflected an ideal where state, society, and religion were bound together. Religion still formed the basis for the social consensus and the church sanctified the state's right to rule in exchange for military and civil protection.

Two other major watersheds still color approaches to religion and power today: the French Revolution and the emergence of Marxist-Leninist thought. The French Revolution represented a fierce, outright rejection of the authority of the "Two Estates": the royals and noblemen, and the church. The two were linked as the enemies of the people, and in the heyday of the Revolution all signs of religious authority and practice, starting with landed estates and extending to the very names of days and months, were eliminated. Many clerics died or fled and church properties were confiscated. What was promoted instead was a civic religion—a deeply secular state stripped of the symbols as well as the practical power embodied in religious institutions. The ideas behind the French Revolution emerged from the prior centuries of Enlightenment thinking and notably, where religion was concerned, of Spinoza and Voltaire. The crux of Enlightenment thinking was to question the authority of religion and other uncritically accepted beliefs. One impetus for this thinking was the catastrophe of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which shook beliefs and encouraged a deep rethinking of acce...