![]()

1

Face Recognition

Andrew W. Young

MRC Applied Psychology Unit, Cambridge, UK

The ease with which we usually recognise familiar faces can hide an interesting perceptual feat. Faces form a class of stimuli with high inter-item similarity (two eyes, nose, mouth, in similar positions) and often with an arbitrary mapping to semantic information (the face gives little away as to whether its bearer is an actor or a stockbroker), yet because of their overwhelming social importance we are highly expert at identifying them.

Here, I examine what recent studies have taught us about the organisation of face processing abilities. As well as considering everyday and laboratory recognition of familiar faces, I pay attention to the implications of face recognition impairments caused by brain injury, and the importance of the interaction between data from investigations of normal and disordered recognition in advancing our understanding.

Face Processing as an Important Achievement

Any member of a species with a complex social organisation needs to be able to recognise other individuals, in order to be able to interact with them in different ways. For humans, the face is especially important to recognition. In addition, a wealth of social information other than identity can be derived from the face. We use this to infer moods and feelings, to regulate social interaction through eye contact and facial gestures, to support speech comprehension by lip-reading (even people with normal hearing do this without realising it), to determine age and sex, and to attribute characteristics on the basis of social stereotypes.

These uses of facial information have a long evolutionary history (Grüsser & Landis, 1991). They are well developed even in infancy, and are probably built up from a basis of innately specified components. Newborn babies are attentive to faces (Johnson, Dziurawiec, Ellis, & Morton, 1991), they can perceive different emotional expressions (Field, Woodson, Greenberg, & Cohen, 1982), and they will imitate both emotional and relatively conventional facial gestures (Field et al., 1982; Meltzoff & Moore, 1983; Vinter, 1985).

We also know a little about the neural substrate for face processing from neurophysiological studies (Desimone, 1991; Gross & Sergent, 1992; Heywood & Cowey 1992; Perrett, Hietanen, Oram, & Benson, 1992; Sergent, Ohta, & MacDonald, 1992). The cerebral cortex contains many neurons that are maximally responsive to faces, especially in the temporal lobes, though there is as yet no evidence of any sizeable region in which there are exclusively “face” cells.

Even without this evolutionary and biological background, there are reasons to suggest that faces form a special class of visual stimuli (Ellis & Young, 1989). In particular, there are different environmental demands between the tasks of recognising people’s faces and many other visual objects. Everyday objects often need to be assigned to relatively broad categories that maximise the visual and functional similarity between exemplars; if you are knocking a nail into a wall, it is important to know that a particular object is a hammer, knowing which hammer it might be is not always necessary. Face recognition presents a quite different type of problem. Galton (1883) pointed out that faces form a visual stimulus category that contains many similar items; each with two eyes, nose, mouth and so on in roughly the same general arrangement. But recognising a face as a face does not get us very far. Instead, we need to know which individual’s face we are looking at, and the smallest of differences may be crucial in determining this.

The relation between form and function is also different. The shapes of manufactured objects are generally closely related to the functions they must perform, so that one could expect to tell fairly easily whether a novel object was likely to be a tool or a piece of furniture. This is much less true for faces. Although there are some pointers (pop stars are usually young people with exuberant hairstyles, etc.), there is a fundamentally arbitrary mapping to semantic information; you can’t really know whether the face of an unfamiliar young person with an exuberant hairstyle is that of a would-be pop star, actor, student or hairdresser.

For all of these reasons, investigations of face processing present an important opportunity to study some of our most highly developed visual abilities with stimuli that are rich in social meaning. Here, I will examine what recent studies have taught us about the organisation of face processing abilities, and the recognition of familiar faces in particular. As well as considering everyday and laboratory recognition of familiar faces, I will examine some of the implications of face recognition impairments caused by brain injury, and the importance of the interaction between data from investigations of normal and disordered recognition in advancing our understanding.

Functional Models of Face Processing

One of the dominant themes of 1980s work on face recognition was the attempt to map out the functional organisation of the face processing system in a simple schematic form. The aim of this was not to pretend that we had solved the problem, but to provide a convenient way of synthesising what was known and guiding further investigation (Bruyer, 1987).

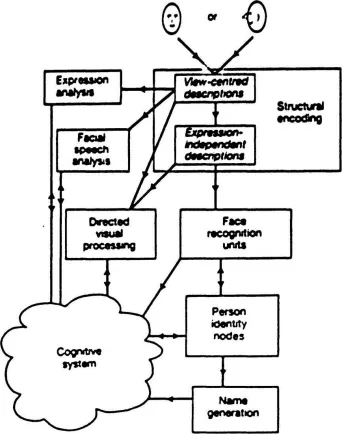

The model proposed by Bruce and Young. (1986) is shown in Fig. 1.1. They maintained that recognition of identity, expression, lip-reading and directed visual processing can all be independently achieved. Hence Bruce and Young claimed that one does not need to interpret a person’s facial expression in order to lip-read, or to determine their sex in order to recognise their identity, and so on.

Fig. 1.1 Functional model of face processing proposed by Bruce and Young (1986).

Instead, Bruce and Young (1986) proposed that recognition involves sequential stages of perceptual classification (by domain-specific face recognition units), semantic classification (involving domain-independent person identity nodes which can access previously learnt semantic information from the person’s face, voice or name) and name retrieval. This was meant as an idealised sequence, and would be compatible with a “cascade” mode of operation. Bruce and Young based these claims on a range of mutually corroborative sources of information, including the results of work on the different patterns of impairment that can follow brain injury, experiments with normal subjects, and studies of everyday errors. Recent reviews of this evidence can be found elsewhere (A.W. Ellis, 1992; Young, 1992; Young & Bruce, 1991), and I will only reiterate some of the main points here.

Recognition and Other Face Processing Abilities

One of the most important claims made by the Bruce and Young (1986) model is that different types of information are extracted in parallel from the faces we see. I will examine briefly four of these putative dissociations. These involve identity and expression, sex and identity, familiar face recognition and unfamiliar face matching, and lip-reading. A more detailed discussion can be found in Young and Bruce (1991).

Identity and Expression

Studies of normal subjects have found that people can classify or match the expressions of unfamiliar faces just as quickly as familiar faces (Bruce, 1986a; Young, McWeeny, Hay, & Ellis, 1986a). This lack of any influence of face familiarity on expression processing is consistent with the view that independent systems are involved in determining identity and expression.

The same conclusion follows from neuropsychological studies. There are some brain-injured patients who remain able to understand emotional facial expressions, despite being unable to recognise familiar faces (Bruyer et al., 1983; Tranel, Damasio, & Damasio, 1988). The opposite dissociation has also been reported, with impaired comprehension of facial expressions even though the identities of the people can be recognised (Kurucz & Feldmar, 1979; Parry, Young, Saul, & Moss, 1991).

Sex and Identity

Some prosopagnosic patients are correctly able to determine the sex of seen faces, even though they can no longer recognise their identities (Bruyer et al., 1983; Tranel et al., 1988), but the opposite dissociation (recognition of familiar faces by someone who cannot determine the sex of unfamiliar faces) has not yet been reported in neuropsychological cases. These neuropsycho-logical findings thus leave open the possibility of a perceptual hierarchy in which the face’s sex is determined before its identity.

However, findings with normal subjects favour the view that sex and identity are determined independently. Bruce, Ellis, Gibling and Young (1987) asked people to classify faces as familiar or unfamiliar, or as male or female. They found that faces whose sex was difficult to determine were recognised as familiar just as quickly as faces whose sex was easy to determine, which is inconsistent with any hierarchy in which sex must be determined before identity. Similarly, Roberts and Bruce (1988) noted that masking various facial features had different effects on determining a face’s sex or familiarity; concealing the eyes had the greatest detrimental effect on determining familiarity, whereas it was concealing the nose area which had the greatest effect on determining sex.

Roberts and Bruce’s (1988) findings show neatly that judgements about sex and identity may dissociate because these draw on cues which primarily involve different regions of the face. They are consistent with other evidence indicating that the face’s three-dimensional structure is particularly important as a source of information for the person’s sex (Bruce, 1990; Enlow, 1982). For example, Enlow (1982) has pointed out that the relatively larger lung capacity of males creates the need for larger nasal passages and thus a more convex facial profile. We will return to this point later, when we consider the roles of pattern and surface-based information.

Familiar Face Recognition and Unfamiliar Face Matching

From his review of neuropsychological studies, Benton (1980) argued that identification of familiar faces and discrimination of unfamiliar faces involve different cerebral mechanisms. Warrington and James (1967) had demonstrated that impairments affecting the processing of familiar or unfamiliar faces were associated with different lesion sites, and there were several reports that prosopagnosic patients (whose recognition of familiar faces is severely impaired) were successfully able to perform face matching tasks. Benton’s position has been supported by more recent studies, which have reported contrasting patterns of impairment of ability to recognise familiar faces or match views of unfamiliar faces (Malone, Morris, Kay, & Levin, 1982; Parry et al., 1991).

However, Newcombe (1979) has pointed out that we need to know not only that prosopagnosic patients can match unfamiliar faces successfully, but also that they achieve this in the normal way. There are grounds at present for suspecting that at least some use idiosyncratic strategies to compensate for their problems with unfamiliar face matching tasks.

Despite this caveat concerning the neuropsychological evidence, the independence of certain aspects of familiar and unfamiliar face processing is supported by studies of normal subjects (Bruce, 1988; Young & Bruce, 1991). A clue to at least one of the reasons for differences between familiar and unfamiliar face processing lies in the finding that somewhat different facial features are involved (Ellis, Shepherd, & Davies, 1979; Young et al., 1985b). The internal features (eyes, nose, mouth) are particularly important in the processing of familiar faces, whereas with unfamiliar faces we make relatively more use of external features (hair, face shape). This differential salience may accrue to the internal features of familiar faces because these remain unaffected by changes in hairstyle or from the attention paid to them because of their expressive characteristics.

Lip-reading

McGurk a...