eBook - ePub

Patterns of Life History

The Ecology of Human Individuality

Michael D. Mumford, Garnett S. Stokes, William A. Owens, Garnett Stokes

This is a test

- 514 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Patterns of Life History

The Ecology of Human Individuality

Michael D. Mumford, Garnett S. Stokes, William A. Owens, Garnett Stokes

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This work summarizes an ongoing longitudinal study concerned with the nature of human differences as manifest in peoples' life histories. The traditional models for the description of human differences are reviewed, then contrasted with the presentation of alternative models. This volume is also one of the few to investigate different approaches to measurement procedures. Practical applications of these models and the results obtained in a 23 research effort are discussed.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Patterns of Life History an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Patterns of Life History by Michael D. Mumford, Garnett S. Stokes, William A. Owens, Garnett Stokes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Approaches to the Study of Human Individuality: Science and Individuality | 1 |

The mythology of science describes researchers untangling the complexities of natural phenomena through the objective, dispassionate application of logic and the power of the human mind. Undoubtedly, this myth reflects certain truths concerning the methods and style of scientific research. Yet through long hours and myriad disappointments, what sustains the individual tucked away in the dark bowels of some ancient building is a passionate commitment to some form of knowledge and understanding that transcends pure logic. Although the ensuing discussion presents a variety of logical arguments stemming from an examination of the results obtained in a rather extensive investigation, like most efforts of this sort, it also reflects a nearly compulsive fascination with a particular natural phenomenon; in this case, the development, meaning, and manifold manifestations of human individuality.

This is not an especially novel preoccupation. One of the most obvious facets of human existence is the uniqueness of the individual, and down through the ages the nature of human individuality has been debated by poets, priests, scholars, and peasants. Some of the reasons for this perennial debate are quite easy to identify. From the dawn of culture, mankind has been required to make a variety of decisions concerning the individual. For instance, individuals must be allocated to the available jobs or training programs, selected for leadership positions or public office, chosen as potential friends or mates, and occasionally evaluated by a jury of their peers. Because there is often a lack of other information on which to base these decisions, humanity has found it necessary to analyze the characteristics of the individual and to use this information in selecting a course of action. When this is coupled with the fundamental import and costs of many of these decisions for both the individual and society, it is hardly surprising that the topic of individuality has preoccupied many. Substantial empirical support for the practical importance of basing decisions on the characteristics of the individual may be found in Schmidt, Hunter, McKenzie, and Muldrow’s (1979) observation that a failure to employ this information may cost organizations billions of dollars each year, but its true importance may be clarified by considering the possible consequences of placing a paranoid in the Oval Office.

On a more subtle level, the course of history and the quality of our lives may occasionally be influenced by commonly held beliefs concerning the nature of human individuality. An example of this phenomenon may be found in the nature-versus-nurture controversy. Traditionally, some people have believed that an individual’s characteristics were the result of ingrained and immutable hereditary predispositions, whereas others have believed that they were the end product of a unique series of past experiences. This latter belief suggests that actions may be taken, by the government or other agents, that will “improve” the individual, whereas the former belief suggests that little can be done to change him or her. When the belief in the nurture argument was dominant in the 1960s and 1970s, a number of actions were taken by the American government in an attempt to induce desirable changes in individuals. Although it continues to be difficult to evaluate the success of these efforts, there is little doubt that the actions associated with this belief, such as affirmative action programs and increased social security benefits, have had a profound effect on American society.

Obviously, this suggests that the nature of human individuality is not a value-free topic. The use of aptitude, ability, and intelligence tests as descriptors of an individual’s characteristics and a basis for decisions has been sharply criticized in recent years. Essentially, critics argue that standardized tests yield an inappropriate and artificial description of the individual that is employed in sorting people into the lords, vassels, and serfs of American society. Others argue that such assessments serve an important purpose in a world of limited resources where both the individual and society are benefitted by an optimal allocation of the available talent (Tyler, 1974). Within the context of the present discussion, it is impossible to resolve this conflict, partly because it is a political dispute that involves a tradeoff between equity and equality considerations. Nevertheless, the existence of this conflict and the importance of the decisions that are tied to our conceptions and assessment of human individuality point to the importance of sound scientific investigations of the phenomenon.

Of course, it has often been argued that the scientific study of any topic as nebulous as human individuality represents little more than an exercise in futility. Certainly, any single attempt to study human individuality as an observable natural phenomenon is unlikely to provide answers to many of the questions that mankind has posed in this regard. Moreover, such an effort cannot address the political issues laid out heretofore, nor can it define the essence, soul, or value of a particular person. In our opinion, these matters are best left to philosophers and the courts. Nevertheless, the development of human individuality is a natural occurrence, and so it should be possible to employ the observational logic of science in an attempt to obtain at least a limited, albeit consensual, understanding of the phenomena. Certainly, its conceptional and pragmatic importance would seem to warrant a substantial effort along these lines, even bearing in mind the limitations that are inherent in the scientific method.

Individuality and Psychology

The importance of human individuality has not been completely ignored in the social sciences, although it has not received the attention it deserves in recent years. Traditionally, the study of human individuality has been the province of psychology. Although definitions of the nature and goals of psychological research differ, general agreement exists that psychology’s primary task entails the description, prediction, and understanding of behavior. Behavior may be observed in many forms, and any given behavioral act is a complex event that, in both its conception and expression, is influenced by a variety of factors. Some of the factors underlying a behavioral act may generalize across a number of organisms, whereas others may be specific to a single organism. Yet, in all cases, behavior will be a property of an individual organism. In other words, such variables as physiology, drugs, and social structure may influence behavior, but it is always a single organism that will emit the consequent behaviors.

If behavior is a property of the individual organism, it follows that psychology’s attempts to describe, predict, and understand behavior must also be tied to the individual organism. Cognizance of this fact has made the individual the central referent in psychological theory (Vale & Vale, 1969) but not necessarily the central referent in relevant research methods. In its attempt to progress as a science, psychology has been forced to address the issue of what constitutes individuality. Unfortunately, a fundamental question has involved conceptualizing and quantifying individual behavior within a replicable operational methodology.

To date, one of the best descriptions of the parameters within which studies of individuality must operate is Kluckhohn and Murray’s (1949) comment that each person’s behavior is like the behavior of “all other men, some other men, and no other men” (p. 46). Ideally, psychological research concerned with the nature of human individuality should examine behavior in relation to all three of these levels. Unfortunately, the truly idiosyncratic, or the ways in which a person is like no other person, are beyond the scope of the analytical tools of social science. On the other hand, despite its relevance to understanding individual behavior in the broadest sense, the ways in which a person’s behavior is like the behavior of all others prevents defining the individual as a separate being with unique behavioral properties. Hence, by default, psychological studies of human individuality have come to focus on the ways in which the individual’s behavior is like that of some other persons. Historically, this area of endeavor has been referred to as involving measurement and the psychology of individual differences, and in the remainder of this book an attempt is made to examine individual differences as a natural phenomenon along with psychology’s varied attempts to formulate a science of human individuality within the context of differential behavior.

Issues in the Study of Individuality

At present, the field has not reached any consensus with respect to a single most appropriate methodology for use in attempts to describe, predict, and understand human individuality (Mischel, 1969). The existence of multiple schools of thought has led a number of scholars to suggest that the study of human individuality, like psychology as a whole, remains in a pre-scientific phase of development (Kuhn, 1970). A number of general issues are likely to be important in any effort to study individuality. In the following paragraphs, the general issues are explored, and the various strategies that have been employed in the study of human individuality, along with their relative strengths and weaknesses, are discussed.

As previously stated, studies of human individuality must focus on the ways in which the behavior of the individual is similar to or different from the behavior of others. What, at first glance, seems to be a rather straightforward requirement has been the source of a number of problems. Most problems stem from the fact that individuality will be reflected in all those behaviors that different individuals display with different frequency or intensity. In a more technical sense, a legitimate indicator of individuality exists whenever variance among individuals exceeds that attributable to random measurement error. Thus, the sheer number of behaviors that could be legitimate indicators of individuality prohibits a comprehensive description of every person in terms of all their discrete behaviors. Consequently, a perennial problem entails determining how information derived from various indicators of individuality across persons may be summarized in a viable description of the individual. Given the fundamental importance of this issue, it is hardly surprising that it has been a major source of controversy.

All attempts to summarize the differential characteristics of individuals are based on either an explicit or implicit classification of the relevant indicators or persons into categories based on some conception of the similarities and differences between them. These categories then form a basis for formulating a summary description of individuality. Fleishman and Quaintance (1984) have noted that there are a number of different methods that might be employed in classification efforts and a number of different ways in which similarities and differences may be defined. For instance, classification can be made on the basis of inferential logic, deductive logic, or statistical covariation. Similarity may be defined on the basis of the frequency with which a behavior is expressed or its intensity of expression. Given manifold approaches to classification, it is hardly surprising that some disagreement exists concerning the manner in which a summary description of human individuality should be formulated.

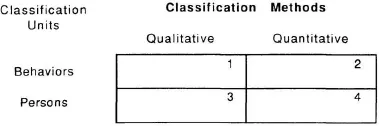

Because classification efforts represent a topic beyond the scope of the present discussion, it is not possible to examine the subject in any detail. However, there are certain general points bearing on the description of human individuality that should be noted. Figure 1.1 presents a schematic representation of the strategies that may be employed in classification efforts. It is intended to convey two general notions. First, classification may be carried out either through qualitative observational and theoretical considerations, or through quantitative empirical relationships. Second, the units being classified may be either individuals or their behaviors.

Fig. 1.1. Classification strategies.

That is, classification and summarization of behavior can be carried out either by assigning individuals to different categories on the basis of their behaviors or by assigning behaviors to different categories on the basis of their expression by an individual.

Studies of human individuality generally incorporate three specific implementations of these generic strategies. First, differential behaviors are often classified and summarized on the basis of their pragmatic or theoretical significance with respect to a particular phenomena of interest. This strategy falls into cell 1 of Fig. 1.1, and its use is illustrated in numerous experimental studies and in the construction of many tests. For example, in the development of content-valid achievement tests, an attempt is made to identify and combine a set of responses to test items that reflect academic performance in some domain across both persons and situations. A second implementation involves summarizing differential behavior by combining behaviors that display a high degree of overlap across persons. This is accomplished by identifying and combining indicators of differential behavior that give similar descriptions of individuals, as indexed by the extent of their intercorrelations or by the stability with which individuals are ordered in terms of frequency, intensity, or correctness. Summarization attempts of this sort fall into the second cell, and this strategy is often used in the construction of personality tests. Finally, pre-existing groups of observational or theoretical significance, such as males, females, successful salespersons, or schizophrenics, are sometimes used to summarize differential behavior by identification of the behaviors that are characteristic of each of these groups. A statement assigning a person to one of these categories can then be used to summarize a wide variety of differential behaviors. Illustrations of this approach may be found in the procedures employed in the construction of life history keys and vocational interest inventories, and these measures would fall into the third cell of Fig. 1.1.

The preceding procedures for formulating summary descriptions are not necessarily mutually exclusive (Gough, 1957). In fact, most studies employ some combination of both the qualitative and quantitative methods for the classification of behavior. Yet it is also true that most investigations tend to focus on a particular classification strategy, and application of different strategies may yield very different descriptions for the individual. For example, the summary descriptions obtained through application of cell 2 procedures would incorporate a set of manifestly similar or homogenous behaviors, but the summary descriptions obtained through application of cell 3 procedures would incorporate a very diverse set of behavioral indicators. Because these summarization strategies provide the groundwork for any study of human individuality, yet may not yield comparable descriptions of the individual, the selection of an appropriate classification strategy is an important issue that should be based on both the problem at hand and the perceived nature of human individuality. Unfortunately, this topic has not received a great deal of attention, in part because psychology lacks a well-grounded understanding of individuality in behavior (Fiske, 1979).

Assuming that an appropriate method has been selected for summarizing differential indicators, the issue of how much generality should be sought arises; that is, whether a summarization should be applicable to a single individual, a group of individuals, or all human beings. The relative value of the idiographic and nomothetic approaches has been debated at length in the literature (Lamiell, 1981). The distinction becomes blurred if a description is targeted on a limited segment of the population, such as individuals over age 65. Despite this confusion, the choice is an important one because it implies a tradeoff between the descriptive accuracy characterizing the idiographic strategy and the generality, efficiency, and parsimony associated with the nomothetic strategy.

After specifying the indicators and the level of generality needed for application across individuals, the summarization may be operationaliz-ed and employed in the description of a particular individual. In opera-tionalization the individual’s status on the indicators included in a summary category can be used to obtain a quantitative description of the individual through some subset of psychometric and experimental techniques (Guilford, 1954). However, because there is not likely to be any absolute criterion available for defining individuality, description of a particular individual is generally carried out through a comparative or relativistic strategy. In experimental studies, this is accomplished by comparing the behavior of an experimental group to the behavior of some control group and ascribing differences to all individuals undergoing the experimental treatment. In psychometric studies, the performance of a given individual on the operational summarization is compared to the typical performance of the members of a normative group. In certain cases, the normative comparisons may be replaced by ipsative comparison, in which the individual’s performance is assessed in relation to personal performance on other summarizations or in other experimental conditions. The ipsative strategy is most often employed in conjunction with an idiographic approach. Regardless of the particular procedure being employed, the description of the individual must be parsimonious in the sense that the summary categories should be limited to the smallest possible number required to obtain an adequate description, prediction, and understanding of differential behavior.

The meaningfulness or practical significance of the description of individuals derived from a particular summarization of indicators is of substantial importance, because there must be some assurance that a viable summary description has, in fact, been formulated. Scientific and pragmatic concerns have resulted in a two-fold approach to this problem. Initially, it had been incumbent on researchers to establish the reliability or robustness of a particular summary description by demonstrating that it reflected variance among individuals above and beyond that which may be attributed to measurement error or chance expectation. Although some ambiguity exists in determining exactly what constitutes measurement error (Thorndike, 1949), various indices of reliability, along with cross validation and replication efforts, have proven to be of some value. Additionally, researchers should attempt to establish the meaningfulness or validity of a summary description by determining the extent to which (a) the indicators incorporated in a summary description provide an adequate sample of the relevant domain or category of differential behavior (content validity); (b) the description of individuals obtained from the summarization is related to other indicators of differential behavior of some significance (criterion related validity); and (c) the summarization manifests a meaningful pattern of interrelationships with other indicators of individuality (construct validity). Though construct validity subsumes content and criterion related validity (Messick, 1980), the most clearcut evidence of the effectiveness of a summary description of individuality is often provided by focusing on predictive validity.

Differential psychology has expended a great deal of effort on the study of procedures for the operationalization and validation of a summary description of individuality. However, a somewhat more nebulous issue has been the effect of differing assumptions regarding the causal locus of individuality. Some investigations assume that individual differences in behavior can be attributed to the particular sequence of environments and learning experiences to which the individual has been exposed, whereas others assume that they are the result of enduring, perhaps hereditary, predispositions that are properties of the individual rather than the environment. Labels such as nature versus nurture and trait versus state philosophies have often been applied to these divergent perspectives. Although psychologists have not been able to resolve this debate in nearly a century of its cyclical reemergence in the literature, there can be little doubt that the assumptions that investigators make in this regard have had a substantial impact on the methods employed and the results obtained in studies of human individuality.

Approaches to the Study of Human Individuality

Over the course of the years, the varied attempts of psychologists to address the foregoing concerns have led to the emergence of four major methodological approaches to the study of human individuality. Experimentation has long been the psychologist’s favored vehicle for the study of human behavior as a general phenomenon. Although experimental methodology ha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series Foreword

- Preface

- 1. Approaches to the Study of Individuality: Science and Individuality

- 2. Studies of Individual Development and Their Implications

- 3. A Prototype Alternative for the Description of Individuality

- 4. Background Data in Formulating Prototypes

- 5. General Methods and Bias Checks

- 6. Cross-Sectional Results

- 7. Sequential Results

- 8. The Composite Summary Dimensions

- 9. Description of the Composite Prototypes

- 10. Evaluation of Composite Prototypes

- 11. Comparative Findings

- 12. Theoretical Implications: A General View of Human Individuality

- 13. Technical Implications: Methodological Considerations in the Description of Human Individuality

- 14. Practical Implementation Strategies for Applying the Prototype Model

- 15. Retrospective and Parting Comments

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Citation styles for Patterns of Life History

APA 6 Citation

Mumford, M., Stokes, G., Owens, W., & Stokes, G. (2013). Patterns of Life History (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1616430/patterns-of-life-history-the-ecology-of-human-individuality-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Mumford, Michael, Garnett Stokes, William Owens, and Garnett Stokes. (2013) 2013. Patterns of Life History. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1616430/patterns-of-life-history-the-ecology-of-human-individuality-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Mumford, M. et al. (2013) Patterns of Life History. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1616430/patterns-of-life-history-the-ecology-of-human-individuality-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Mumford, Michael et al. Patterns of Life History. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.