![]()

Chapter 1

Laying the foundations for teaching writing

Introduction

Being able to write is a gateway to empowerment. Not only does academic success in most countries still depend on writing as the dominant mode for assessing learning, but being able to write gives access to social and cultural power. Think of the very real consequences of a well-written letter of complaint, or an incisive report on an important issue, or an emotionally persuasive campaign leaflet. And there is little doubt that the power of the message is shaped by the medium: it is not just the persuasiveness or authority of what is communicated but the way in which it is written. A PGCE student who had worked in a well-known high-street store once reported that scruffy, badly expressed letters of complaint were simply thrown in the bin on the basis that their authors were unlikely to put up much of a fight! But writing is also about how we express and understand ourselves and how we communicate with those closest to us, be that a verse composed for a Valentine’s card or a chatter on MSN. Writing can hold records of the past and shape visions of the future; it can bring down politicians and build up personal relationships; it can make us laugh, weep or scream. Yet writing is not a natural activity.

Unlike learning to talk, which almost all of us learn naturally through our social interactions, writing is a more deliberative activity which has to be learned. Critically, from the perspective of this book, it is an activity which has to be taught. And it is a highly complex activity, requiring us to shape our thoughts into words, frame those words into sentences and texts which are appropriate for our intended audience and purpose, and pay attention to shaping letters, spelling words, punctuating sentences, and organising the whole text. Kellogg (2008) suggests that engaging in a writing task is as mentally demanding as playing chess. And unlike many other activities which are initially hard to learn but become easier with practice, writing remains a highly demanding activity even as we become more experienced. Even though many of the aspects of writing which are highly effortful for very young writers, such as shaping letters, understanding word boundaries, spelling and punctuation, do become automatised in older writers, the effort involved in these activities transfers to higher-order activities related to increased expectations of what texts can or should do. Writing your first academic assignment at university can suddenly make you feel like a novice all over again!

This chapter sets out to offer you an overview of research and theoretical thinking about the writing process and the teaching of writing. We hope it will demonstrate that there are multiple perspectives of the writing process, drawing on different ways of thinking about writing, and that it will challenge you to reflect on your own practice as a teacher of writing.

Writing as a social act

The dominant theoretical view of writing at present is that writing is a social act; in other words, when we write, we are participating in a social practice which is shaped by social and historical understandings of what writing is and what texts should do. When we teach children to write, we teach them what is valued by our culture. For example, English culture tends to place a high premium on accuracy in spelling, and in academia or the workplace, spelling errors are frowned on. But there is no reason why spelling should be so significant – Shakespeare managed very well without standardised spelling, and it would be a quite reasonable position to argue that spelling only matters when errors impede the communication of meaning. The importance of spelling is a culturally validated stance. In the same way, social views of writing distinguish between Standard English and non-Standard English and privilege the Standard version. These examples of what is socially valued in writing are, of course, the views of the powerful and the privileged in our society, and may not be shared by other social groups. A Yorkshire writer may value a text written in Yorkshire dialect much more highly. The way that writing as a social practice is influenced by views on Standard English is highly contested. It was at the heart of national debates about the first National Curriculum for English in 1988, and Brian Cox, the architect of the first version, argued that learning how to write in Standard English was an entitlement: ‘in our democracy Standard English confers power on its users to explain political issues and to persuade on a national and international stage. This right should not be denied to any child’ (Cox, 1991: 29). There is a robust body of argument on this issue (Pound, 1996; Crowley, 2003; Myhill, 2011) but, in essence, they all counterpoint the notion of access to Standard English as an entitlement with the notion of dominance and power of the privileged being exerted over those with less social power. The very public debates about spelling, grammar and Standard English are vivid examples of the way that writing is a social practice.

But writing as social practice is far more than the ways in which conventions of accuracy and language use are played out in writing. The way we use language in speech or in writing is fundamentally expressive of who we are and how we create meanings for ourselves. Richardson (1991: 171) argues that language

… begins with everyday experience, with perception, and yet it controls the very way in which we experience, understand and manage our lives. It is a window on to our innermost thoughts, the most intimate part of ourselves as individuals, and yet its words, and the grammatical patterns which shape and hold them together, come entirely from outside ourselves. Our social context teaches us our language, and language makes us ourselves.

Texts themselves are socially constructed and culturally validated artefacts: for example, what is acceptable in a formal letter varies from culture to culture, and expectations about the structure of argument writing are very different in western cultures when compared with Chinese culture. Written genres are sociological constructions, representing particular views and values, and shaped by the communities who use them. Swales (1990: 42) defined genres as ‘goal-directed communicative events’, or as Martin (1985: 250) expressed it, ‘Genres are how things get done, when language is used to accomplish them’. Genres in school are often taught rather formulaically as a fixed set of conventions, whereas theoretical views of genre are more diverse, recognising that genres have an essential stability, but that they are also flexible and negotiable. Genres represent ‘preferred ways of creating and communicating knowledge within particular communities’ (Swales, 1990: 4) but they shift, transform and evolve through the communities who use them.

Young writers do not simply reproduce the genres they encounter or are taught; they actively use them to make sense of their life experiences and their literacy experiences. In this way, writing is an act of social meaning-making: learning to make meaning in texts is about learning to make meaning in contexts. Dyson (2009) illustrates how Marcel, an enthusiastic footballer, appropriated and adapted social practices in writing, drawing on both his own experience and understanding of football commentaries and of written conventions. His report on a football match is set out like a television sports report ‘borrowing the symbolic and graphic arrangement of score-reporting practice’ (ibid.: 237). He does not observe left-to-right conventionality but sets out his text with vertical directionality, inviting the reader to read downwards, not across. This mirrors the visual text presentation he has seen on television. But he inserts the words ‘in Texas’ between his column of team names: Dyson suggests that this represents the voice of the commentator reading the score, which the writer has transformed into written text. Marcel draws on his own social experiences to adapt and shape his writing. Marsh (2009) and Merchant (2007) have both illustrated how young writers draw on their out-of-school experiences of popular culture and of digital technology to shape their writing in school. And although writing in school is dominated by linear verbal text, many researchers (Kress, 1994; QCA/UKLA, 2004; Walsh, 2007; Kress and Bezemer, 2009) have shown how writers in both the primary and secondary age phases use their understandings of multimodal constructions of text to inform the way they compose texts and shape meanings. Walsh (2007) describes young writers as multimodal designers who develop ‘repertoires of practice’ (ibid.: 79) in which they creatively and imaginatively transform their knowledge of writing in the world to recreate their own meanings in text.

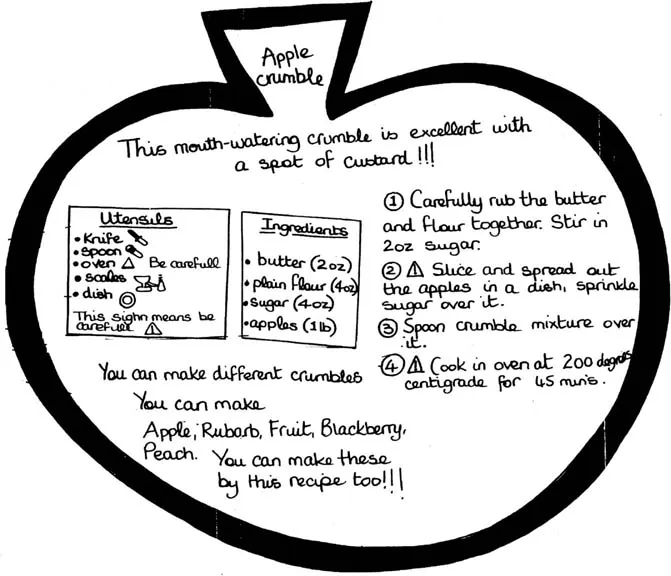

We can see this exemplified in Figure 1.1 below. It was written in school by Tasha, an eight-year-old, following lessons on how to write instructional genres. She has been taught about how instructional texts include lists and diagrams to help the reader, and how instructions are often given through the use of imperative verbs. You can see clear evidence of these features in her text. But she moves beyond what has been taught to design a text which combines the visual and the verbal, with the catching apple shape enclosing the recipe, and with elements of the persuasive genre blended with the instructional genre. She tries to encourage her readers to have a go at this recipe by enticing them with ‘This mouthwatering crumble is excellent with a spot of custard’ and she signals the usefulness of this recipe in making other fruit crumbles which ‘you can make by this recipe too!’

Figure 1.1 Instructional text incorporating both multimodal and persuasive features

Source: Springer Science and Business Media (2005). Used with permission.

Tasha is writing within a community of practice framed principally by the expectations of school writing; but she also uses wider community knowledge, perhaps her own experience of recipe books at home in the family, to support the creation of her text. As a writer, she brings to the classroom a unique set of social, cultural and literacy experiences which remind us that ‘every child’s pathway to literacy is a distinctive journey shaped by personal, social and cultural factors’ (Bradford and Wyse, 2010: 140) and that every act of writing is an act of social meaning-making.

Language development in writing

Children begin to build their knowledge and understanding of writing well before they are formally taught to write. Their social and environmental experiences of print teaches them how print makes meaning and by the time children begin school they have already developed a significant repertoire of understandings about writing. Of course, the nature of this repertoire is very varied, depending on the individual child’s social and cultural experiences. Rather than thinking of early years children as non-writers, we should think of them as emerging writers. The notion of emergent writing owes much to the breakthrough work of Teale and Sulzby (1986) who first showed how children ‘emerge’ as fully fledged writers through a series of developmental steps. Writing development begins with the earliest marks children make on paper and their growing awareness of symbolic representation, that the marks carry meaning. Early mark-making may be as simple as lines or squiggles on paper, but Lancaster (2007) demonstrated that children under two could distinguish between writing, drawing and numbers, showing a high level of symbolic understanding. These early marks develop into more deliberative writing practice, although still pre-writing rather than writing. Children begin to scribble, drawing straight and wavy lines, and they may include drawings or scribbles which look like letters, even if they are not from our alphabet. Then they start to use random letters and increasingly letter strings, some of which may look like words. All of these pre-writing activities are important developmentally: they support both the refinement of fine motor skills and understanding of writing as a meaning-making enterprise.

The first steps of more formal writing develop alongside the development of handwriting skills. Young writers have to learn about the orthography of writing, the way language represent spoken words in written form. Initially, this involves learning about the left-to-right directionality of print, the shaping of letters, and discriminating words as separate linguistic units. In speech, although we use words, the boundaries between them are not visible in the way they are in writing. Some very common words in English are the outcome of a historical word-boundary confusion at a time when most of the population were not literate. The word ‘apron’, for example, was originally ‘a napron’ and word-boundary confusions led to its current usage. Young writers often write in what is called scriptio continua (Ferreiro and Teberosky, 1982), a continuous stream of text with no spaces between words. Once young writers have a fair grasp of phonics and grapheme-phoneme correspondences, they can attempt new words for the first time using invented spellings. Invented spelling ‘plays an important role in helping children learn how to write. When children use invented spelling, they are in fact exercising their growing knowledge of phonemes, the letters of the alphabet, and their confidence in the alphabetic principle’ (Burns, et al., 1999: 102). It also indicates that the child is thinking on their own about the relationship between letters, sounds and words.

Once young writers have mastered these crucial basic processes in writing, there is a well-documented trajectory of linguistic development which can be traced through the primary age range. In particular, young writers have to learn about the sentence as a unit unique to writing (Kress, 1994) and the many options and varieties for different syntactical structures. In the UK, the two studies by Perera (1984) and Harpin (1976) are the most significant. Both found that clauses and sentences increased in length with age, and that whereas young writers use simple active verbs, they become increasingly adept at using more complex constructions, such as the passive and modal verbs. They found that writers move from using coordination as the means of joining two sentences to an increasing use of subordination (a finding confirmed more recently by Allison et al., 2002). Perera’s research also indicated that noun phrases lengthen and become more complex with age, but that primary writers sometimes have difficulty mastering appropriate use of pronouns and causal and adversarial connectives. Many of these linguistic trajectories continue in the secondary phase, but there are some subtle differences. More able writers in their teenage years develop greater variety in sentence structure and length, so a developmental feature is not increasing sentence length and increasing subordination, but achieving greater variation in sentence length and greater use of the simple sentence alongside sentences with subordination (Myhill, 2008). They also vary how their sentences start, not relying on repeated use of the subject in the start position. Indeed, the key characteristic of linguistic development in the secondary age range is variety, both lexical and syntactical. Older writers are better able to compose texts with readers in mind, making word and image choices and varying syntactical structures for rhetorical effect.

A further characteristic of language development in writing is learning the difference between talking and writing. Writing is not speech written down: indeed, if we did write as we speak it would look extremely odd and be very difficult to follow, as speech is typically full of long, often unfinished utterances, with hesitations, rephrasings and repetitions. Speech is also very dependent on the context in which it takes place and many words in speech refer to a shared understanding of the context; for example, the utterance ‘this one’ will almost certainly be accompanied by pointing to something which both speaker and listener can see. In writing, young writers have to develop what Kress call ‘the habit of explicitness’ (Kress, 1994: 37), providing the right level of detail and information to help an unseen reader understand the text. Wells and Chang (1986) note the difficulty young writers have in transferring from speech to writing, particularly because the absence of response and feedback from the reader puts all the responsibility on the writer to sustain the writing. In effect, they have to imagine their reader and their reader’s responses.

Evidence from Loban’s (1976) study suggests that although writing and talk appear to develop in tandem, language constructions found in speech did not appear in writing until about a year later. Perera (1986) found that by age eight, most children are able to distinguish between speech and writing and use few specifically oral constructions in their writing: in other words, ‘children are differentiating the written from the spoken language and are not simply writing down what they would say’ (Perera, 1986: 96). At the secondary stage, whilst no writers write literally as they speak, the influence of oral linguistic patterns on writing is a feature of less able writers who have not yet acquired confidence with more writerly forms (Myhill, 2009a).

Cognitive models of writing

Research into psychological models of writing have focused on the cognitive processes and sub-processes which are involved in the act of writing. Perhaps surprisingly, given the rich reservoir of research on cognitive processes in reading, the first cognitive model of writing (Hayes and Flower) was not published until 1980. It is therefore still a relatively young field of research. The model proposed by Hayes and Flower was generated through investigating how writers described their composing process: they asked them to ‘think aloud’ – that is, to say what they were thinking as they wrote. From this information they devised their model, which suggested that there were three core processes involved in writing:

• Planning: this describes the process of organising oneself to write and generating the ideas for writing. It includes thinking about the nature and ...