- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Language, Cognition, and Deafness

About this book

First published in 1987. This book is intended as an introduction to the field of communication and deafness, with particular reference to cognition and the various forms of language used by hearing impaired people. It is aimed at an audience comprising teachers and student teachers of the deaf, speech pathologists and students of speech pathology, social workers and students of social work, psychologists and students of psychology and, to some extent, the parents of deaf children and deaf people themselves. It attempts to provide a concise summary of the topic and, indeed, as well as being for the audience just described, it will be useful to anyone with an interest in the psychological, sociological, and linguistic ramifications of hearing loss.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

PSYCHOLOGY, AUDIOLOGY, AND DEAFNESS

In this chapter, we set the scene for subsequent discussion. We begin by describing the nature of hearing impairment and its complex (and often misused) terminology. Then we discuss what to most people is the major effect of deafness—the poor speech and lipreading skills of hearing-impaired people and their associated difficulties with spoken language. Finally, we introduce the concept of deafness as a social, rather than psycholinguistic, phenomenon.

The general term hearing impairment can be defined as loss of hearing that is severe enough to produce disorders of communication requiring remedial or educational treatment. The disability is, like most, a continuum, but it can be for practical purposes divided into two distinct groups—those children, adolescents, or adults who are deaf and those who are hard of hearing. In childhood, deaf children or students with impaired hearing require education by methods suitable for pupils with little or no naturally acquired speech or oral language. Hard of hearing children or students are those with impaired hearing whose development of speech and oral language follows the same pattern as their hearing peers, although not necessarily at the same rate. Such students require special educational provision, but not necessarily the same educational methods as are used for deaf students.

The classification of deafness into the categories of deaf and hard of hearing is useful in schools and elsewhere, but it does mask one important variable, the age of onset of deafness. Specifically, depending on whether deafness occurs congenitally, before or after the development of language, or on whether deafness occurs in childhood or in adult life, the effects on the individual vary both qualitatively and quantitatively. Therefore, the terms deafness and hard of hearing should invariably be qualified by one of two adjectives—prelingual or adventitious—which specify the age of onset, or they should be replaced by the term deafened when adventitious hearing loss occurs in adult life.

Obviously the definitions just described represent rough classifications rather than definitive statements. One consequence of this has been a failure on occasion to identify and consider a separate group of children and adults who present unique problems—the prelingual profoundly deaf. As the name implies, these individuals have no residual hearing for practical purposes and their handicap precedes the development of speech and language because it occurs in approximately the first 2 years of life. Many such deaf adults and students are, in practice, congenitally deaf and have etiologies of genetic origin. In all cases, they have been subject to severe sensory, oralaural language and emotional deprivation. They present unique problems, and although audiologically and linguistically speaking it may be proper to regard deaf, hard of hearing, and hearing individuals as forming a continuum, psychologically they do not. Indeed, considerable harm can result and has resulted from a failure to appreciate the special problems facing deaf children in infancy and in later stages of development. Throughout the remainder of this text we refer to and, indeed, are mainly concentrating on deafness, and we usually apply this term to that group of individuals who have severe or profound hearing losses predating the acquisition of spoken language. The term hard of hearing refers to those with lesser but significant degrees of handicap, and the term hearing-impaired refers usually to deaf and hard of hearing people collectively.

Unfortunately, the literature on deafness and on hard of hearing students and adults frequently fails to make the distinctions described in the previous paragraph. The terms also have sociological as well as audiological or psychological ramifications. Therefore, we are not always able to maintain the distinctions with complete clarity, particularly because in a number of major studies of hearing-impaired people, it is difficult to know exactly which group formed the focus of the research. What we do is try to avoid making statements about deaf people that more correctly refer to hard of hearing people, and vice versa; a common and unfortunate failing in the literature. It is this failure that allows us to believe in the fiction that deaf people are able to function psychologically, educationally, and socially in the same way as hearing people. They cannot, which does not mean that deaf people are in some ways inferior, but rather that they interact with their environment in a different way.

Prevalence of Hearing Impairment

The preeminent demographer of deafness is Jerome D. Schein of New York University. Written with Marcus Delk, his study of The Deaf Population of the United States (Schein & Delk, 1974) provides a wealth of data on the status of the American adult deaf population. For the younger age range, the population of students in schools, programs, and classes for the hearing-impaired in the United States is surveyed annually by the Center for Assessment and Demographic Studies at Gallaudet College, and the College publishes informative and interesting data on the characteristics of these students. However, the survey itself does not establish prevalence rates, because it surveys students who are already in programs for the hearing-impaired, rather than the population at large. In practice, an unknown number of hearing-impaired children are either misdiagnosed or never even identified; many others are diagnosed later in life than is either technically necessary or educationally desirable (e.g., Lyon & Lyon, 1981–82; Rodda & Carver, 1983).

At the time of writing, another major prevalence survey is being undertaken in the United Kingdom by the Medical Research Council’s Institute of Hearing Research, but the final data have yet to be published. Preliminary reports by Davis (in Lutman & Haggard, 1983), and by Haggard, Gatehouse, and Davis (1981) indicate an overall prevalence rate of 4.5% for significant hearing impairment in the population of the United Kingdom (roughly a Better Ear Average Hearing Level, BEA of 45dB, see p. 7). This rate is somewhat lower than that found by Schein and Delk (1974), but the definition of significant hearing impairment is probably a little more conservative.

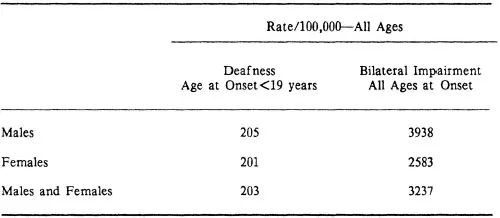

Table 1.1 is based on the data of Schein and Delk (Tables II.10 and II.11, pp. 28/29). It is surprising to the uninitiated because it shows hearing impairment to be a problem of some magnitude. Even prelingual profound deafness is not the small problem it is often assumed to be. In fact for prevocational deafness, the prevalence rate is about twice (2/1,000 population) the rate that we have characteristically used for planning purposes in the past (1/1,000). The difference explains why it was possible for Rodda (1970) to locate samples of deaf students in the United Kingdom that were more than 100% of the estimated total population, and also explains a number of other similar discrepancies in the demography of deafness. As Schein and Delk (1974) clearly established, hearing impairment is a major educational problem, and it probably explains far more academic retardation and developmental delay than we are aware of. In the United States alone there are an estimated 13.5 million adults (6.6% of the population) who have some degree of hearing impairment, of whom about 400,000 became deaf before the age of 19 years and 200,000 before the age of 3 years.

TABLE 1.1

Prevalence Rates for Deafness and Hearing Impairment in Civilian, Noninstitutionalized Population of the USA in 1971

Prevalence Rates for Deafness and Hearing Impairment in Civilian, Noninstitutionalized Population of the USA in 1971

Source—J.D. Schein and M. Delk, 1974, The Deaf Population of the United States, tables II.10/II.11, published by the National Association of the Deaf.

The Cause, Measurement, and Remediation of Hearing Loss

It is not the purpose of the text to provide basic information on the ear, hearing, and audiology (the science of hearing assessment and aural remediation). Nevertheless, it is important to provide some information in order for the reader to understand what causes hearing loss and what the terms deafness and hearing impairment mean in a concrete sense.

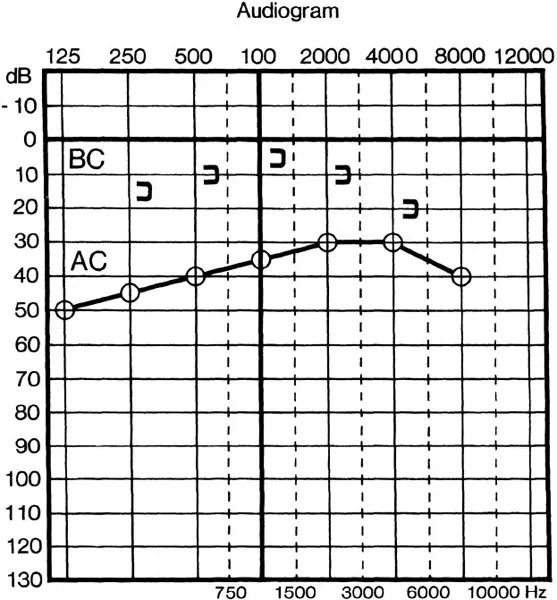

An Audiogram

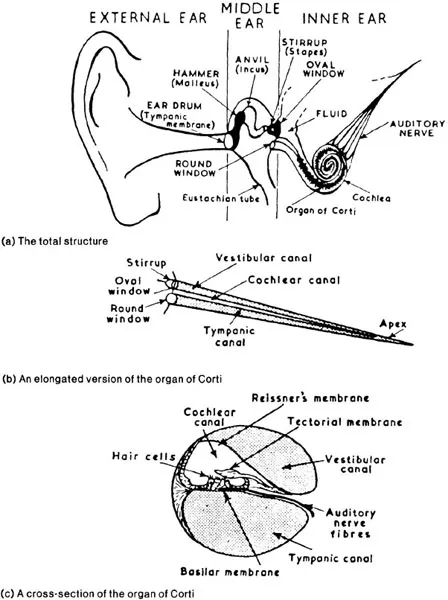

Figure 1.1a shows a schematic diagram of the ear and Fig. 1.1b a pure tone audiogram. The two axes of the audiogram record the degree of hearing loss in decibels (dB), and frequency of the pure-tone sound used in testing in hertz (Hz). The line marked zero is the theoretical level of hearing of average unimpaired young adults. In practice, the average young adult probably hears a little better because the zero line reflects a statistical average, and it includes some older and some mildly impaired ears. For this reason and because we are dealing with averages, hearing losses on the audiogram can range from -10dB to +110dB. Scores outside these ranges are not usually possible because they reflect the range of conventional audiometric equipment. However, the audiologist, particularly at the upper limit, will sometimes note a “No response” (NR)—meaning that the hearing may be worse than the maximum possible hearing loss shown on the audiogram.

FIG. 1.1a. A schematic diagram of the ear.

Source—M. Rodda (1967), Noise and Society, Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd.

FIG. 1.1b. Shows a pure-tone audiogram. AC is testing when sound is presented through the external ear. BC is testing when the sound is presented through a vibrator.

The BEA loss refers to the average hearing loss in dB in the best ear for the most important frequencies for the reception of speech, generally regarded as 500, 1,000 and 2,000 Hz but sometimes including 4,000. However, hearing losses can and do vary with frequency. For example, sometimes losses are greater in the higher frequencies than in the lower ones, and the shape of the audiogram assists the audiologist in diagnosis and remediation, as do many other tests of speech, sound, and hearing reflexes.

In Fig. 1.1b, the curve marked ‘AC’ shows a right ear air conduction audiogram, in which the sound is presented through earphones in the normal way. Curve ‘BC’ shows the bone conduction audiogram for the same ear, and in this case the sound is presented through a tactile vibrator, usually placed behind the ear. In bone conduction the sound is conducted in three ways. Inertial lag results in movement of the stapes (see Fig. 1.1a) resulting in movement of the oval window, and the organ of Corti, the main receptor of hearing, is also stimulated directly. In addition, the vibration of the skull causes the air in the outer ear to vibrate, and some sound is conducted through the normal air conduction route. These three sources of sound are called inertial, distortional, and osseotympanic bone conduction respectively. Hearing losses affecting the mechanical parts of the ear are called conductive; those affecting the organ of Corti and auditory pathways are called sensori-neural. Air conduction measures both conductive and sensori-neural losses and does not distinguish them. Bone conduction separates conductive from sensori-neural losses, and so provides important diagnostic information.

Causes and Types of Hearing Loss

Sensori-neural hearing losses can be subdivided into those resulting from damage to the organ of Corti in the ear itself, and those (sometimes called central losses) occurring in the neurological processes that transmit the sound signals up to and including the cortical areas of the brain. The adjectival descriptions we apply to different degrees of hearing loss are:

| BEA Pure Tone Loss | |

| Normal | −10 to 25dB |

| Mild | 26 to 40dB |

| Moderate | 41 to 55dB |

| Moderately Severe | 56 to 70dB |

| Severe | 71 to 90dB |

| Profound | >91dB |

A motor mower approximates to a sound intensity of 90dB, and people with profound hearing losses will not be able to hear this sound or a normal telephone bell even when they are close to them. They might get a slight sense of vibration. Conductive losses are invariably less than 60dB and, therefore, any loss above this level must include a sensori-neural component.

Deaf people usually have hearing losses in the severe or profound category, but because deafness implies membership of an ethnic group (pp. 42 to 43) some deaf people may have quite mild impairments and may on rare occasions even be hearing.1 Hearing children of deaf parents are also sometimes bicultural—members of both the hearing and the deaf communities. Definitions are arbitrary, and we refer to these special situations only so the reader clearly understands that the audiological definition of deafness is only one way of looking at the problem.

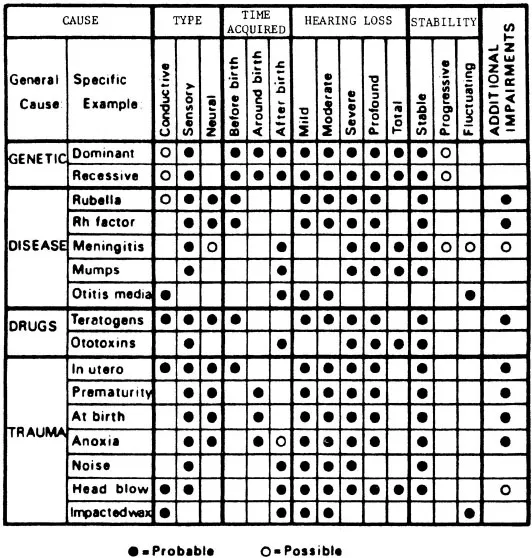

The causes of deafness are many and they are constantly changing. Figure 1.2, reproduced from Boothroyd (1982, p. 50), is a useful synopsis, and it also shows the type of hearing loss associated with each cause, the time it can affect hearing and whether the loss is always the same (stable), whether it becomes progressively worse (progressive) or whether it varies in severity (fluctuating). Impacted wax is probably the most frequent cause of a mild hearing loss, and it is easily and completely treatable. A number of other conductive losses often can be alleviated by medical treatment, and those that are not responsive to treatment can be helped considerably by a properly fitted hearing aid. Sensory and neural losses cannot be cured medically, and a cochlear implant is still only a crude aid to hearing (perhaps more correctly described as an aid to lipreading). Rubella epidemics still occur, although their effects are less severe because rubella vaccination has protected at least part of the population at risk, pregnant women. Unfortunately, there are still many females of childbearing age who have not been vaccinated, and still others who do not realize that a periodic booster vaccination is necessary.

FIG. 1.2. Cause...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Credits

- Contents

- Preface

- Dedication

- 1. Psychology, Audiology, and Deafness

- 2. The Cultural Context

- 3. The Linguistic Status of Sign Language

- 4. Cognitive Factors in Communication

- 5. Language Development and Educational Issues

- 6. The Physiological Basis of Communication

- 7. Social and Emotional Development and the Problem of Counseling

- 8. Current Trends and Final Conclusions

- References

- Glossary of Some Additional Terms

- Name Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Language, Cognition, and Deafness by Michael Rodda,Carl Grove in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.