![]()

I

PSYCHOLOGY AND OPERATIONAL POLICING

The behavior of police at the worksite (e.g., on the street, in a private home, at the police station or in a jail cell, in the interview or line-up room) is influenced by a range of psychological factors. A knowledge and understanding of how these factors operate suggest a number of ways for enhancing the performance of the individual police officer and the police organization as a whole. The chapters in this first section of the volume provide a clear and insightful overview of research in mainstream psychology that can be used to inform police about various operational policing matters.

In the first chapter, Wilson and Braithwaite illustrate how a range of psychological variables influence the behavior of police on patrol. Police behavior during interactions with citizens is shown to be a function of the officer’s personality, background, training, and socialization, and of the manner in which these variables interact with situational, environmental, and social psychological pressures. These variables determine the likelihood that an officer will succeed in acting in a way that avoids conflict occurring, or de-escalates conflict when it does occur. Police administrations concerned with minimizing the level of conflict in interactions between police and citizens will be assisted by an awareness of the psychological research that identifies the critical variables associated with aggression and conflict escalation.

Fildes’ chapter on driver behavior and traffic safety (chapter 2) provides an interesting review of psychological research which highlights the role that police can play in the prevention of unlawful driving behavior such as speeding or driving while under the influence of alcohol. This research confirms that where law enforcement procedures are grounded in sound psychological theory, validated by empirical evidence, police can expect to have an active role to play in preventing as well as reacting to undesirable road user behavior.

In chapter 3, Gottfredson and Polakowski provide a concise review of a complex literature on the determinants and prevention of crime. In reviewing some of the important correlates of crime, they argue that much crime is committed by individuals characterized by low self-control, with this being largely a product of experiences, relationships, etc. in the early childhood or adolescent years. Not surprisingly, given this position, they argue that police sanctions are unlikely to impact markedly on crime prevention, a conclusion that many police may find hard to accept. However, they do show how police efforts are likely to be more effective if they target the restriction of opportunities for criminal acts, and increasingly broaden their focus in order to recognize and to deal with the complex psychological and social determinants of crime.

Chapters 4, 5, and 6 on the topics of interviewing witnesses, face reconstruction, and eyewitness testimony and identification all provide a clear demonstration of the important role that psychological research findings should play in the refinement of operational procedures. Thus, for instance, chapter 4 (Fisher & McCauley) provides convincing evidence illustrating how interviewing eyewitnesses using the “cognitive interview” will often increase the amount of relevant (accurate) information a police officer obtains from an eyewitness. In so doing, they present clear guidelines on the basic principles associated with conducting the cognitive interview. Similarly, Bond and McConkey illustrate in chapter 5 how research on memory also has significant implications for the design of procedures used in attempts to reconstruct images of offenders’ faces (cf. identikit photos), and for the purposes for which they might be used (i.e., recognition or recall). Guided by psychological research on how and what people remember (and forget), their chapter provides a critical evaluation of a number of different approaches to face reconstruction. In chapter 6, Thomson provides a detailed overview of those variables that can facilitate and distort the testimony provided by eyewitnesses. He illustrates how characteristics of the event, the situation, and the witness influence testimony, reviews the evidence on various identification procedures, and examines the effect of delay (and intervening events) on testimony and identification. A detailed knowledge and understanding of variables contributing to the accuracy of testimony and identification has important implications for the performance of police investigators.

In the last chapter in this section (chapter 7), Iacono evaluates the techniques for evaluating the accuracy or reliability of offender testimony. He highlights the problems that can arise when police depend on techniques such as polygraphy that do not stand up well to careful evaluation. Iacono also describes and evaluates other techniques (e.g., the guilty knowledge test, possibly coupled with the measurement of cerebral potentials) which are typically ignored by police administrators, despite the availability of evidence demonstrating their efficacy. Thus, this chapter indicates that attention to the results of research is not only critical for developing techniques, but also critical to the ongoing evaluation of techniques currently in use.

Together, the chapters in this first section highlight the important contributions that psychological research can make to the refinement of a number of different aspects of police operations. It seems that police cannot afford to disregard what research in psychology and other behavioral sciences has to offer. At the same time, it is important that psychologists continue to evaluate results from the laboratory under the real world conditions in which police must operate.

![]()

1

Police Patroling, Resistance, and Conflict Resolution

Carlene Wilson

National Police Research Unit, Australia

Helen Braithwaite

The Flinders University of South Australia

Police patrol work is commonly perceived to be a dangerous undertaking, principally because it involves contact with potential and actual offenders. However, although the potential for officers to experience confrontation in their daily activities is certainly high, officers are only rarely assaulted, and full compliance by suspects to officers’ requests or no contact at all with potential offenders are much more frequent outcomes (Wilson & Brewer, 1991). This is not to negate the fact that officers sometimes are placed in dangerous situations in which a conflict escalates to the point where injury is sustained by police, suspect, and/or bystander. By attempting to develop an understanding of the variables that distinguish these dangerous encounters from the more frequently occurring benign interactions, risk to both officers and the public can be minimized.

A considerable body of research in the past 2 to 3 decades has focused on the identification of those variables that impact upon the probability that conflict will escalate and, more particularly, the likelihood that a police officer will experience physical resistance. This research, originating from a wide range of criminological, sociological, and psychological perspectives, highlights a range of environmental, situational, personal, and interpersonal variables that contribute to the risk for the officer on patrol. This chapter provides an overview of these research results, focusing primarily on those variables over which the individual police officer and/or the police organization can exert some control, as opposed to variables like offender characteristics which, while having a significant influence, are largely destined to remain outside of the realm of police influence.

A BEHAVIORAL MODEL EXPLAINING CITIZEN RESISTANCE TO POLICE

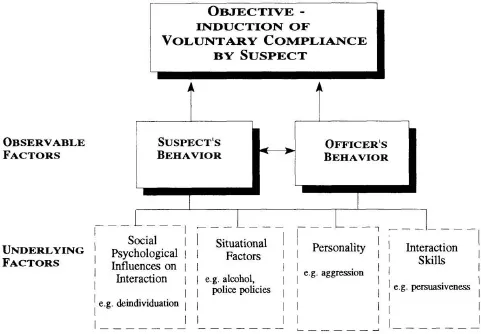

We have chosen to take a behavioral approach to the analysis of resistance encountered by police while on patrol because this seems to provide the best opportunity for developing a systematic intervention model designed to minimize risk. It is our contention that risk is primarily determined by the behavior of the parties in a confrontation situation, and that this behavior in turn is dependent upon, to a greater or lesser extent, a variety of psychological influences—the personality and interaction skills of the suspect, the personality and interaction skills of the officer, situational constraints on the exchange, and a variety of social psychological factors that impact in any interaction. This model is diagrammatically summarized in Fig. 1.1.

The basic premise of this model is that the primary behavioral aim of the officer on patrol is to maintain order and, where necessary, to enforce laws, through the obtainment of suspect compliance (Richardson, 1974). Ideally this compliance will be voluntary, thereby minimizing risk to all participating parties. However, the ability of the officer to achieve the goal behavior—the voluntary compliance of the suspect—will be dependent on the characteristics of both the suspect and the officer, on some aspects of the situation, and also on factors identified in social psychological and other research, which influence the nature and outcome of interactions, especially when participants’ goals diverge. The remainder of this chapter summarizes the research in psychology that bears upon these issues—specifically research investigating social psychological and situational variables that influence outcomes in interpersonal situations, personality and conflict resolution, the skills and tactics used in gaining compliance, as well as how these sets of factors influence the behavior of the officer and of the citizen during an interaction. Sometimes these areas of research will overlap, reflecting the complexity of the factors determining outcomes in interactions. Each section includes a summary of any research that has focused primarily on police. On this basis it will be possible to attempt to integrate the findings from research in psychology into a more broadly encompassing model of police patrol, highlighting the variables that determine the nature of the police-citizen interaction. The chapter concludes with the application of the model to the development of a framework for the management of the risk associated with patrol.

FIG. 1.1. Factors influencing the ability of police to induce voluntary compliance.

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGICAL INFLUENCES ON THE OCCURRENCE OF CONFLICT

One area of concern for social psychologists is the nature of group processes, and how these can impact upon the behavior of the individuals who constitute the group. These processes include those oriented to intergroup dynamics, as well as those involved with intragroup interactions. These social psychological processes have been shown to influence attitudes and behavior in a range of laboratory and field experiments. The most graphic demonstrations of these processes have involved conflict situations (e.g., Sherif & Sherif, 1953).

The police officer on patrol, whether he or she patrols in a group, as a pair, or even alone, is acting as a representative of a well-defined and easily recognizable group. As a consequence, the officer’s behavior while acting as a representative of this group is constrained by group norms and expectations as well as by individual preferences. In addition, both the officer and the public have a set of well prescribed perceptions of the role and function of police. For example, the roles of law enforcer and peace keeper are well accepted by both police and public as legitimate police concerns which can dictate behavior in a variety of social situations. Both of these roles also serve to heighten intergroup competition and conflict with those who would wish to break the law or disturb the peace, while maximizing intragroup unity and conformity among officers upholding the law.

The specific social psychological processes involved in the development of intergroup conflict have received considerable research attention. Pioneering research in this area was undertaken by Sherif and associates (e.g., Sherif & Sherif, 1953; Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood, & Sherif, 1961) who described a process of conflict generation, later labeled “realistic group conflict theory” (R.C.T., Campbell, 1965), in which competition in the form of “real conflict of group interests causes intergroup conflict” (Campbell, 1965, p. 287). These conflicts of interests serve to promote both antagonistic intergroup relations, and enhance intragroup cohesiveness, thereby dichotomizing in-group from out-group members.

Deindividuation

Subsequent work has focused on the specific explanatory variables that can predict the behavior of ingroup members toward outgroup members. Deindividuation is one of the variables that can be used to predict successfully the likelihood that an individual in a conflict situation will act in a way dissonant with their normal personal preferences because he or she is freed from the constraints that operate upon individual behavior (i.e., he or she is deindividuated). Deindividuation has been defined as the process whereby “antecedent social conditions lessen self-awareness and reduce concern with evaluation by others, thereby weakening restraint against the expression of undesirable behavior” (Prentice-Dunn & Rogers, 1980, p. 104). It is particularly potent in situations where the potential for violence is high.

The process of deindividuation is facilitated by circumstances that highlight group cohesion and by situations in which arousal is maximized. In the former situation it would appear that a sense of shared identity, a common role, or both, may serve to accentuate group unity and the salience of out-group differences; and consequently to increase the likelihood of deindividuation. Evidence for this comes from a number of sources, including descriptions of mob behavior and laboratory situations set up to study the process. Other studies that have attempted to foster group cohesiveness have reported that successful manipulations of this sort increased perceived unity.

Police are a strongly cohesive group in the community brought together by a common role, and easily identifiable as a distinct group. Occupational socialization, together with a strong paramilitary component to training, ensures the cohesiveness of the group. In addition, participation in duties that can in some circumstances be described as highly arousing, serves to accentuate the influence of deindividuation, thereby increasing the likelihood of impulsive responding (Guttmann, 1983; Mark, Bryant, & Lehman, 1983).

Experimental evidence further suggests that commitment and belief in ingroup membership does not depend upon the presence of a large number of fellow ingroup members, with two members sufficient to produce a more competitive untrusting orientation towards an outsider in certain situations (e.g., Pylyshyn, Agnew, & Illingworth, 1966; Rabbie, Visser, & van Oostrum, 1982). This finding suggests that the typical two-officer patrol is not immune to influence from social psychological variables like deindividuation.

This brief summary of theory and research in deindividuation provides us with the framework from which we can make a number of predictions about the behavior of police on patrol. Police patroling in groups, even small groups (e.g., a pair), and/or those officers dealing with more than one suspect, will be influenced by the constraints of group membership and, consequently, demonstrate the influence of deindividuation. Thus it can be predicted that such an influence should be evidenced as a more aggressive approach to the resolution of a patrol activity undertaken by two or more officers, in comparison to the approach taken by a solo-officer, especially i...