1

THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN EVIL AND GOOD

On 19 July 64 a great fire broke out in the city of Rome. It began amid shops between the Palatine and Caelian hills, and the fire immediately became so fierce it could not be contained. It blazed rapidly through the low parts of the city then began to climb the seven hills. The palaces of the rich burned as did the wooden tenements of the poor, and witnesses told of the panic that ensued. Women, children, and the elderly were trapped in flaming narrow streets and screams of the helpless rose over the roar of the flames, while rumors spread that some people were openly hurling torches to keep the fire blazing as it consumed more and more of the city. Finally, after burning for five days, the fire was contained by the erection of a huge firebreak around the flames. When the smoke settled, Romans could see with horror that of the fourteen districts of the city, only four were left unburned. Three were completely leveled, while the remaining seven had only a few half-burned houses left.1

The unpopular emperor Nero opened the public buildings for the homeless and brought in food to provide for the newly destitute Romans, but his popularity did not increase. People muttered that he had started the fire so he could make room for a new huge palace for himself. Others said that he appeared on a private stage and sang of the destruction of Troy as he watched the fire burn.2 Roman priests offered prayers and sought to propitiate the gods and goddesses who had so far guarded the city so well, but popular sentiment was not satisfied. As Tacitus wrote, “But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the propitiations of the gods, did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration was the result of an order.”3 Nero then hit on an ingenious way to deflect anger and suspicion: he accused Christians of starting the fire. Tacitus does not tell us why he selected Christians, writing only that he selected a “class hated for their abominations” who followed “Christus,” a man killed “at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus.”4 Nero may have selected Christians because as a new sect they had little support among the large population of Rome. He may also have been influenced by his wife Poppaea’s favoritism to the Jews, many of whom fiercely objected to Christians (see chapter 5). Whatever his motives, Nero introduced the first persecution of the Christians by Romans, and he did so in spectacular fashion.

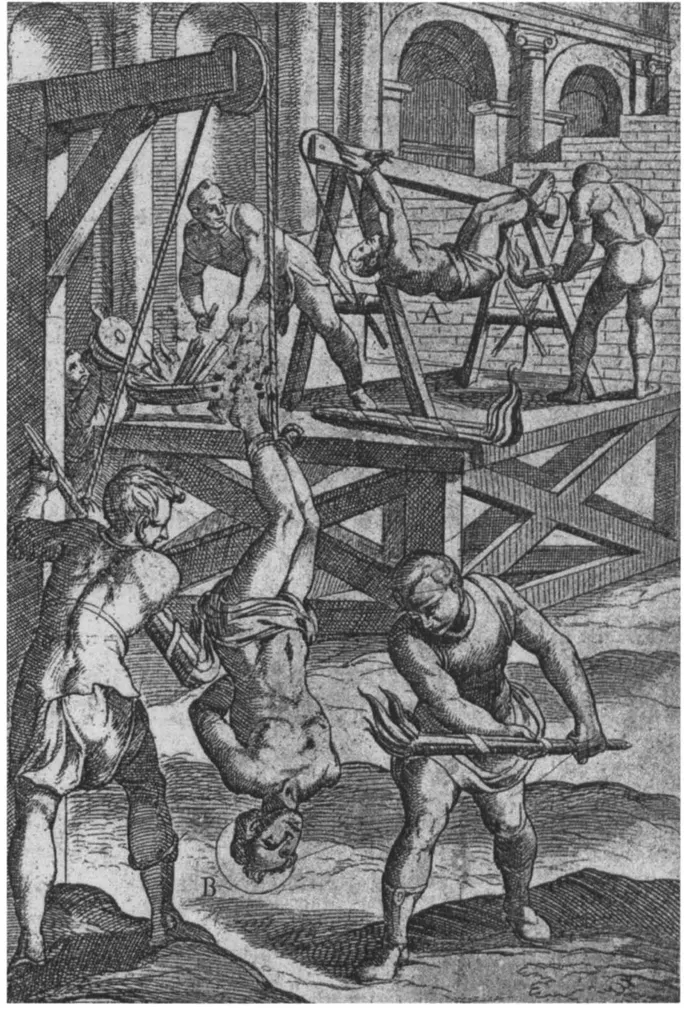

Nero had his soldiers arrest everyone who claimed to be Christian, then tortured them to get names of others in the Christian community. In this way, he arrested hundreds of people. Nero turned their execution into a spectacle designed to please the crowds who had so recently turned their anger on the emperor himself. He had some Christians covered with the skins of beasts and attacked by dogs. Others were crucified or tied to wooden torches and burned alive to illuminate the night. These “executions” were conducted in Nero’s own gardens, and he mingled with the spectators in the costume of a charioteer. Once again, Nero’s excesses offended some of the crowd. Tacitus, who had no sympathy for Christians, noted “even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed.”5

Tacitus had no idea how significant this event was; he reported it as one more bizarre example of the excesses of a cruel and corrupt emperor. The historian rapidly moved on to tell of other more momentous events. But this was a turning point, for the age of martyrdom had begun. Christian communities were no longer quarreling in the synagogues with their Jewish relatives. Now, they had to prepare themselves to confront the power of Rome.

Many of the faithful remembered this horror of persecution when so many were brutally killed, but the most influential articulation of the struggle between good and evil that began in Nero’s garden was written in about 95 by a man named John who had been exiled to the island of Patmos by Emperor Domitian. While on this rocky island off the coast of modern Turkey, John recorded his visions of the upcoming struggles, and these visions, which came in magnificent and frightening images, became the final book of the New Testament—The Revelation to John: The Apocalypse, known as the Book of Revelations.

The Book of Revelations recognized that the age of martyrs had dawned: “For men have shed the blood of/ saints and prophets” (Rev. 16:6), and in this struggle, Christians were set against the power of the state. In John’s vision, a beast rose out of the sea that was “allowed to make war on the saints and to conquer them” (Rev. 13:7), and most commentators identify this beast with the Roman Empire. The “number” of this beast —666—probably referred to Emperor Nero (the sum of the letters in his name).

John’s visions were probably written for Christians outside Rome who had heard of the horrible events. His visions were intended to inspire hope among Christians who John believed would face more persecutions. He promised that God was guiding the struggle and that it would end in victory. Furthermore, the revelation promised justice: The martyrs were in heaven—“I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded for their testimony to Jesus and for the word of God, and who had not worshiped the beast…,” and unbelievers who had persecuted them would be “thrown into the lake of fire” (Rev. 20:4, 15). This book foretold the struggles that were to come and promised an ultimate victory in which Christians would prevail. However, as people interpreted the powerful and compelling images, John’s revelation did more: it cast the struggle between the faithful and the unbelievers into a cosmic battle between good and evil in which the state was evil. As we will see in chapter 8, the cosmic vision had long-standing consequences long after the age of martyrs was ended. When John wrote of his vision, however, the martyrdoms had just begun. The struggle was still new, and even though John fiercely drew the battle lines, Rome did not yet realize it was engaged in a war.

After the violence under Nero, the emperors did not officially per-secute Christians for almost another 150 years. That is not to say that there were no martyrdoms during that time, for there were, but the persecutions were local and took place when provincial officials chose to prosecute. The random nature of these persecutions between 64 and 203 has led to much discussion about what constituted the legal basis for the persecutions, and the answer has remained somewhat elusive, or at least unsatisfying.

Some Romans spread scandalous rumors about their Christian neighbors. The Christian North African Minucius Felix in about 240 listed some of these shocking charges in order to refute them: He said that Christians were accused of gathering together with “the lowest dregs of society, and credulous women.” They met in the dark and despised the temples. They disdained present tortures, yet “dread those of an uncertain future.” They threatened the whole world with destruction, and finally in violation of all propriety, they committed incest, cannibalism, and indulged in orgies after secretive love feasts.6 One can see hints of a badly misunderstood reality within these accusations, for there actually were secret Eucharistic feasts at which Christians who called themselves “brother and sister” exchanged kisses of peace while expecting the destruction of the world.

Christians universally denied the charges of criminal behavior. The church father Tertullian wrote with characteristic sarcasm: “Who has detected the traces of a bite in our blood-steeped loaf? Who has discovered, by a sudden light invading our darkness, any marks of impurity, I will not say of incest, in our feasts?”7 Tertullian was right; none of the trials of martyrs accused them of these charges, although one early martyr (Attalus) was clearly reacting to these rumors when he shouted to the crowd as he was being slowly burned to death: “Look you, what you are doing is cannibalism! We Christians are not cannibals, nor do we perform any other sinful act.”8 Another martyr, Lucius, cried out to the judge as his fellow Christian was condemned: “What is the charge? He has not been convicted of adultery, fornication, murder, clothes-stealing, robbery, or of any crime whatsoever; yet you have punished this man because he confesses the name of Christian?”9 Rome had to decide what their crime was.

Romans were deeply—and rightly—proud of their legal traditions. By the time of the empire, Roman law had developed into a complex system, which was unique in the ancient world because Roman jurists not only wanted to maintain the stability of the state but they also wanted to provide justice. Consequently, when confronted with Christians, Roman authorities were careful to look at the prevailing laws, and they were troubled by the lack of clear direction.

The legal situation was complicated by the fact that in the early empire, citizens and noncitizens were subject to different laws. Citizens were governed by civil law (ius civile), while others were subject to their own laws and customs, which came to be called the ius gentium, or law applying to other nations. Different magistrates administered these two different kinds of laws, so when Christians were arrested, judges first had to ascertain whether they were citizens, then they were tried in the appropriate courts. The penalties for citizens and noncitizens differed, which also determined the legal form of execution. As we shall see, this question of legal status would shape the experience of the martyrs.

The Roman desire for justice and legality led to discussions about the proper treatment of members of this new religious sect. There is a famous correspondence between Pliny the Younger and Emperor Trajan from 112 that addressed the ambiguity of the charges against Christians. By 112, there had been enough sporadic charges brought to the attention of the authorities that Pliny, as a careful provincial governor, wanted an imperial ruling about how to handle these Christians. Pliny told the emperor how the matter had progressed: a number of people came to him and denounced others—both citizens and noncitizens—of being Christian. Since Pliny had never before confronted such a trial, the governor did not know whether the crime was one simply of being a Christian (the “name” itself) or whether they were indeed guilty of vile crimes, as the previously mentioned rumors indicated. These Christians pleaded guilty to the name and were sent off to be executed.

The situation then became more complicated for Pliny. The accusations spread and a large number of people were accused, some of whom were clearly innocent and others who said they had once been Christians but were no longer. Pliny forced the accused to sacrifice by pouring a bit of wine and burning incense before the imperial statue and cursing Christ. Those who performed these rituals were freed. Pliny, however, was made more curious about this cult, and he investigated the matter further to see if they were guilty of any crimes. After questioning people, he found nothing illegal in the life of these people, and even after torturing two Christian slaves (identified as deaconesses) to determine the “truth,” he still found no illegality. They carefully avoided all crime and simply met before daybreak to sing and worship God.

Yet, Pliny found something disagreeable at best in their obstinate refusal to perform the Roman sacrifices for the health of the emperor. Pliny called this a depraved superstition that was intolerable, but the legality of his trials was unclear to him. Thus, he stopped all proceedings until he received a ruling from the emperor. Trajan’s answer was decidedly lenient. The emperor forbade anonymous accusations as contrary to the spirit of his reign, so the governor need not seek out Christians. However, if an obstinate Christian came to the attention of the governor, he should be punished, but if an accused Christian was willing to sacrifice, then all his or her previous “crimes” or associations were forgiven.10

Trajan’s ruling was practical but somewhat inconsistent. In his clear analysis, the fourth-century historian Eusebius noted what many believed: “This meant that though to some extent the terrifying imminent threat of persecution was stifled, yet for those who wanted to injure us there were just as many pretexts left.”11 Tertullian, a little less than a century after the letter was issued, commented with scorn at the legal difficulties implicit in the opinion: “How unavoidably ambiguous was that decision!… So you condemn a man when he is brought into court, although no one wanted him to be sought out. He has earned punishment, I suppose, not on the ground that he is guilty, but because he was discovered for whom no search had to be made.”12 In many ways, Tertullian was right. What was the crime that brought Christians to the attention of the authorities? It was not the crime of not sacrificing because that came after the charges as proof of innocence. No, the charge was simply that of the “name,” and throughout the records of the martyr trials, their profession of the name Christian was enough to condemn them. A group of North African martyrs in 180 are representative. The dialogue is sparse and to the point:

The proconsul Saturninus said to Speratus: “Do you persist in remaining a Christian?”

Speratus said: “I am a Christian.” And all agreed with him.

The proconsul then read the decision: “Whereas [all]…have confessed that they have been living in accordance with the rites of the Christians, and whereas though given the opportunity to return to the usage of the Romans they have persevered in their obstinacy, they are hereby condemned to be executed by the sword.”13

There was no evidence presented, nor were additional crimes charged; the name was enough. Some of the reported trial records include more dialogue with the judge and confessor arguing the merits of each side, but there is never any doubt that the end is as the dialogue between Speratus and Saturninus portrayed.

Trajan’s successor, Hadrian (who ruled from 117 to 138), also issued an edict restricting persecution of Christians. His letter urged his provincial governors to rely strictly on the law, not on rumor or popular demand for persecutions. He wrote, “If then the provincials can so clearly establish their case against the Christians that they can sustain it in a court of law, let them resort to this procedure only, and not rely on petitions or mere clamor.” He further urged the governors to prosecute people who brought charges against Christians for their own financial gain.14 Both Trajan and Hadrian demonstrate that from 64, the persecutions that created martyrs did not originate from imperial policy. Instead, they were local matters stimulated usually by controversy among neighbors.

In 177, a persecution broke out in Lyons in Gaul, and we know many details about this horrible event from a letter by an eyewitness written to inform churches in Asia of the persecution. Christians in Lyons were made unwelcome by their pagan neighbors—they were forbidden to go to the baths, to the forum in the center of the city, indeed, to be seen anywhere at all.15 Were these Christians immigrants from the East (which would explain why the letter relating their fortunes would have been sent back) and thus perceived as foreigners bringing in an unusual cult? Probably, but we cannot know for sure. Nevertheless, ...