eBook - ePub

To-Morrow

A Peaceful Path to Real Reform

This is a test

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

To celebrate the centenary of the first garden city at Letchworth, the Town and Country Planning Association has performed a service to planners everywhere by initiating the republication in facsimile form of the very scarce original first edition of To-Morrow. Accompanied by a running scholarly commentary on the text, and by a newly-written editorial introduction and postscript, jointly written by three leading commentators on Howard's life and work To-Morrow will immediately become a compulsory purchase for every serious student and practitioner of planning and for teachers and students of modern social, economic and political history.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access To-Morrow by E. Howard,Sir Peter Hall,Dennis Hardy,Colin Ward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

POSTSCRIPT

FOR A SMALL BOOK, PUBLISHED WITH THE HELP OF A SUBVENTION BY Howard, and sold for a modest shilling a copy, the influence of To-Morrow must have exceeded even the wildest dreams of its inventive author. No sooner was it published than it led to the formation in 1899 of the Garden City Association, and just four years after that to the start of Letchworth Garden City. The rest is history. Welwyn, the second garden city, took shape after the ending of the First World War. Several attempts to start a third foundered, but the Garden City idea was later to find new life (albeit in modified form) in the ambitious programme of new towns launched by the post-war Labour government in 1946. Additionally, in different countries around the world, throughout the past century various forms of garden city and new town development have enriched the history of Howard’s original idea.

In the first decade of the new millennium the surprising thing is that Howard’s book is still a source of inspiration. It would be easy to dismiss its reprinting now as mere indulgence, just another trip down memory lane, but a reading of the original text accompanied by Peter Hall’s and Colin Ward’s Commentary reveals so clearly why this would be wrong. Simply as a model of coherent advocacy, Howard’s book remains intrinsically interesting for the contemporary reader; if for no other reason it is worth re-visiting as a text brimming with ideas. It touches on numerous themes that, even if some were more pertinent at the time than now, continue to invite critical reflection. But there are also more tangible reasons for this new publication. One is that To-Morrow exercised a strong influence on both ideas and urban planning practice in the twentieth century, not simply in the country where the idea was first promoted but also across the world. A second reason is that, more than a hundred years on, elements of the original thesis might still be relevant to the work of contemporary planners and policy makers.

To-Morrow Yesterday

It would be an exaggeration to claim that the 1898 publication took the world by storm, although its early reprint as a paperback and the volume of sales in the first two years exceeded even the author’s own expectations. Howard was encouraged, too, by a number of favourable reviews from fellow radicals, like the influential land nationalization campaigners. But in this camp he was already preaching to the converted and it was inevitable that others with different priorities were more sceptical. Political critics (particularly from factions on the Left who believed that real change could only be achieved through working-class representation in Parliament, if not by outright revolution) disliked the author’s search for a middle way and poured scorn on his conviction that capitalists could be persuaded by rational argument to change their ways. For them it was all hopelessly Utopian.

Howard, though, was nothing if not determined and in 1899 he joined with twelve like-minded radicals to form the Garden City Association (Beevers 1998, Hardy 1991a). Its aims were simply to promote the ideas in To-Morrow and to prepare the ground for the first Garden City experiment. Like dozens of other well intentioned groups in that period, the newly formed Association might well have lost its way within a few years, in the train of ill-attended meetings, insufficient funds and a dwindling membership. Instead, the cause was soon to be adopted by a small number of liberal-minded ‘men of substance’ led by an eminent lawyer, Ralph Neville (who in 1901 became the Association’s Chairman), and an able organizer, Thomas Adams (appointed as Secretary). Through these individuals the Association was rapidly transformed into a sharply focused organization with its sights set firmly on the task of building the first garden city.

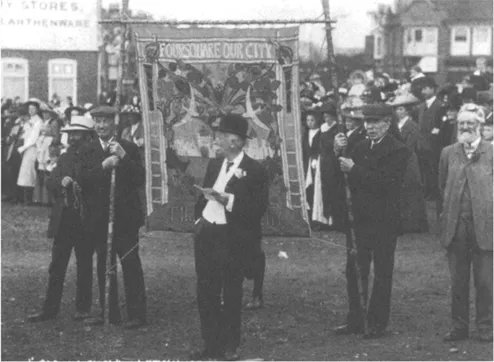

Celebration of Letchworth Garden City Opening Day in 1903.

For Howard himself progress was not without a price. He remained the ‘ideas man’, the inventor, but in other respects he was sidelined by those with a sharper political and financial acumen. The closer the Garden City idea came to realization the more its radical pretensions were stripped away. Neville and his business associates (at odds with the more radical sections of the 1898 text) were constantly at pains to reassure investors that this was not a crypto communist plan for a ‘co-operative commonwealth’ (even though Howard had rather hoped that it would be). When a second version of the book was published in 1902, Howard was persuaded to change the title to Garden Cities of To-Morrow, avoiding any reference to ‘real reform’. And, in due course, when the first garden city was built, it was done without the more contentious elements of Howard’s original plan. Important changes were made to the ways in which capital could be raised, how the community could capture the value of rising rents, how garden cities should be administered, the nature of public services, land tenure, the size of the estate, the area reserved for agriculture, restrictions on growth, and the design layout (Hardy, 1991a, p. 55) To say that what evolved in practice was unrecognizable to readers of To-Morrow would be an exaggeration, but, undoubtedly, in the interests of political contingency important elements of the original concept were jettisoned.

Politics, though, is the art of compromise, and Howard’s willingness to let his sponsors have their way allowed at least some of his ideas to take shape. Sufficient capital was raised and the foundations of Letchworth, the first garden city, were laid in 1903, under the inspired guidance of the chief architects, Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker. In spite of a slow start the emergent garden city was soon to draw tens of thousands of visitors, intrigued by the prospect of a newly found Utopia in the Hertfordshire countryside. Media views of this New Jerusalem were tempered by the experience of trudging across the mud-sodden ground, and later by the sight of prominent groups of eccentrics amongst the pioneer settlers. To outsiders they seemed an odd lot: clad in djibbas and with home-crafted sandals on their feet, invariably practicing vegetarianism, and subscribing to what were regarded as alien beliefs. The fact that it was a teetotal community must have added to the discomforts of visiting journalists; the Skittles Inn, with its Bovril and hot chocolate, was a poor substitute for the real thing (commentary page 105). It was, of course, the exceptional that made the headlines, at the expense of more enduring features, such as the model housing and progressive schools, and the exemplary parks and social facilities that became the mainstays of the first garden city (Miller, 1989).

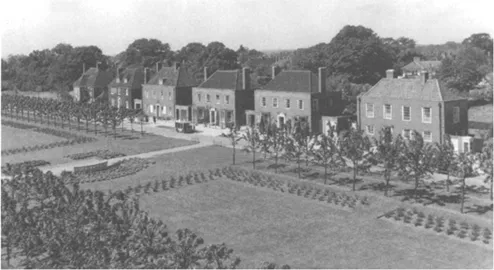

Station Road Letchworth: cottages designed by Parker and Unwin between 1905 and 1907.

Letchworth grew slowly at first but its very foundation was enough to set an unquestionable standard for its keenest advocates. The pages of the Garden City Association’s journal at that time contained regular reports of what was seen elsewhere as the misappropriation for commercial purposes of Howard’s concept. Property developers were quick to spot the attraction of adding the term ‘Garden City’ to what in many cases might have been little more than speculative housing estates. The ultimate transgression was the case of Peacehaven, on the south coast of England, a motley collection of shacks and bungalows that the instigator, Charles Neville, marketed as the ‘garden city by the sea’ (Hardy and Ward, 1984, pp. 71–91).

In the eyes of the purists, though, even worse than developments that were manifestly not garden cities was the growing popularity of the garden suburb. This was a term that was commonly used to describe even the most mundane of suburban developments, although high standards were set by the pioneering and prestigious Hampstead Garden Suburb (designed by no less than Parker and Unwin, following their work at Letchworth). The criticism of the garden suburb was not on grounds of design so much as a fundamental flaw in the very idea of extending the boundaries of large cities. Even the Hampstead development was based on an acceptance that its residents would commute from nearby Golders Green into the centre of London. Garden suburbs, no matter how carefully planned, could simply not, according to the Garden City campaigners, offer the benefits of a totally new settlement built according to the ideas in To-Morrow.

In challenging localized developments, the Association was at risk of becoming too inward looking and might well have campaigned itself into an historical cul-de-sac. In the event, wiser counsel prevailed and the point was taken that what would really matter in the future was to see progress in establishing a proper system of town and country planning for the nation as a whole. Without this, it was argued, Garden City experiments would, inevitably, remain isolated and their very principles would be eroded by schemes owing little to the principles promoted by Howard. Thus, the Garden City Association gradually entered a wider political arena of campaigning, becoming heavily involved in a national lobby for planning. To coincide with the first national planning legislation, the pressure group changed its name and constitution in 1909 to the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association. Within this broader remit, garden cities were no longer the sole or even the prime reason for the organization, and it was left very much to Howard and a core of fellow sympathizers to keep the original flame alight. In 1910 an attempt was made to commemorate the death of the late king with a new garden city, to be called King Edward’s Town, but Edward’s successor, George V, made it known that he would prefer to see more conventional monuments.

It was not until after the First World War that, very much as a result of the personal initiative and insistence of Howard, land was secured for a second experiment, to be known as Welwyn Garden City. In spite of bold statements by the government of the day that homes would be built for returning heroes, Howard remained healthily sceptical: ‘if you wait for the Government to do it you will be as old as Methusaleh before they start’ (Osborn, 1970, p.8). Against all the odds, Welwyn took shape, as Letchworth had done, largely as a product of private capital and dedicated effort. Also like Letchworth, it attracted a great deal of publicity and interest; for a while it was known as the Daily Mail town because of the decision of that newspaper to feature Welwyn in its annual Ideal Home Exhibitions.

The Food Reform Restaurant and ‘Simple Life Hotel’ and the Central Hotel were further examples of Letchworth’s temperance and vegetarianism.

Ebenezer Howard speaking at the Coronation Pageant for George V at Letchworth in 1911.

Welwyn had its radical elements, and visitors were always keen to see examples of what was sometimes erroneously described as communal ownership. They visited the Welwyn Garden City Stores (commentary page 99) and the Cherry Tree Restaurant, and read the Welwyn Garden City News; and they mused over contradictory criticisms that Welwyn was either a socialist Utopia or, conversely, a company town. But if they had doubts on the political front they could hardly miss the evidence of good quality housing and the advantages of a properly planned environment. Howard’s ideas were even more watered down than they were at Letchworth, but Welwyn was still recognizably a garden city. Planned by the architect, Louis de Soissons, the layout combined (to a greater extent than at Letchworth) a mix of modern and traditional features, much liked by the early residents and certainly very much better than what was commonplace in new development at the time elsewhere in Britain (Osborn, 1970).

The second garden city, though, grew slowly in its formative years and was to be the last of its kind. An attempt in 1925 to build a third on a site near Glasgow foundered because of a lack of capital; and in the 1930s an ambitious proposal for a scheme at Wythenshawe, to the south of Manchester, led to housing development but not by a long way a balanced community of the sort Howard had advocated (Deakin, 1989). The fact is that the fashionable trend in planning was moving, increasingly, in favour of greater involvement by the State. Even within the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association (which was, again, in 1939, to change its name to reflect new developments, this time to the Town and Country Planning Association), there was a growing acceptance that the future of planning lay in this direction.

Meanwhile, in other parts of the world the publication of To-Morrow led to parallel histories of garden city development (Ward, 1992). From the outset, partly as a result of successful campaigning by the Garden City Association, Howard’s ideas attracted widespread interest in Continental Europe and beyond. A regular stream of visitors made their way to the Association’s offices and then to Letchworth itself. They returned to their own countries sufficiently enthused to encourage experiments suited to their particular circumstances. An International Garden City Congress was convened and in 1904 held its first convention in London. The main delegations came from Germany and France (each with their own Garden City Association) and the United States, but letters of support were also received from Budapest, Brussels and Stockholm. And there was contact too with enthusiasts in Japan, Australia and Switzerland. Several years later, in 1913, the Association’s Chairman observed that ‘the extent to which this idea has spread outside the limits of our own country is certainly astonishing…we have had enquiries from Russia, Poland and Spain— countries which, in our ignorance, we looked upon as somewhat behindhand in social matters—and we find now they are coming to the front of the Garden City Movement’ (Hardy, 1991a, p. 94).

Parkway, Welwyn Garden City. This early photo appeared on the jacket of Green Belt Cities by Frederic Osborn which was published in 1946.

International interest was matched by experiments on the ground. In France, for instance, a number of cités jardins were built in the environs of Paris—small settlements such as Les Lilas and Drancy, and larger ones like Châtenay-Malabry and Plessis-Robinson—but these were all only partial experiments. The later developments, especially, contained apartment blocks as well as more traditional cottage-style housing. Jean Pierre Gaudin has shown how such experiments (which between the wars were extended to other parts of France), and a wider interest in Howard’s idea of the garden city, appealed both to bourgeois philanthropists and to socialist reformers (in fact, precisely as Howard had intended). Although the cité jardin sometimes bore less resemblance to Letchworth or Welwyn than to a well-ordered industrial suburb, Gaudin points out that the real significance of the experiments was sometimes that of a more far reaching reformist project for citizenship and the urban polity (Gaudin, in Ward, 1992, pp. 52–68). Howard would have approved of that.

Likewise, in northern Europe, there were also applications of the garden city. Germany, for instance, where the idea of social housing had strong roots, was, in fact, a pioneer of garden city development and, indeed, a source of inspiration to some British reformers, if not to Howard himself. The German Garden City Society was formed in 1902 and encouraged a variety of housing experiments gathered loosely under the garden city, or Gart...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Illustrations

- Commentators’ Introduction

- The Facsimile

- Introduction

- I. The Town-Country Magnet

- II. The Revenue of Garden City, and how it is Obtained— The Agricultural Estate

- III. The Revenue of Garden City—Town Estate

- IV. The Revenue of Garden City—General Observations on its Expenditure

- V. Further Details of Expenditure on Garden City

- VI. Administration

- VII. Semi-Municipal Enterprise—Local Option—Temperance Reform

- VIII. Pro-Municipal Work

- IX. Administration—A Bird’s Eye View

- X. Some Difficulties Considered

- XI. A Unique Combination of Proposals

- XII. The Path Followed Up

- XIII. Social Cities

- XIV. The Future of London

- Appendix—Water-Supply

- Postscript

- Bibliography