- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Emperor Constantine

About this book

First published in 2004. The Emperor Constantine provides a convenient and concise intro- duction to one of the most important figures in ancient history. Taking into account the historiographical debates of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Hans A. Pohlsander assesses Constantine's achievements. Key topics discussed include: How Constantine rose to power; The relationship between church and state during his reign; Constantine's ability as a soldier and statesmen; The conflict with Licinius. This second edition is updated throughout to take into account the latest research on the subject. Also included is a revised introduction and an expanded bibliography.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

The emperor Constantine has been called the most important emperor of Late Antiquity. His powerful personality laid the foundations not only of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome and of Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but of post-classical European civilization; his reign was eventful and highly dramatic. His victory at the Milvian Bridge counts among the most decisive moments in world history.

But Constantine was also controversial, and the controversy begins in antiquity itself. The Christian writers Lactantius and Eusebius saw in Constantine a divinely appointed benefactor of mankind. Julian the Apostate, on the other hand, accused him of greed and waste, and the pagan historian Zosimus held him responsible for the collapse of the (Western) empire.

It is the positive view which generally, but not universally, prevailed throughout the Middle Ages, prompted numerous rulers to cast themselves in Constantine’s image, and inspired countless works of art. Otto Bishop of Freising (c. 1114–58), in his Chronica or History of the Two Cities, is full of enthusiasm, writing: “When his associates had reached the end of their reign, and in consequence Constantine was now ruling alone and held the sole power over the empire, the longed-for peace was restored in full to the long afflicted Church. . . . Since wicked men and persecutors had been removed from the earth and the righteous had been set free from distress, therefore, as though a cloud had been dissipated, a joyful day began to gleam forth upon the City of God all over the world.” Conversely Petrarch (1304–74) in his Bucolicum Carmen calls Constantine a miser (wretch) and hopes that he will suffer forever. Here, and also in his De vita solitaria, Petrarch disapproves of the Donation of Constantine.

In more modern times Constantine has come in for some harsh criticism from both philosophers and historians. Thus Voltaire, in his Philosophical Dictionary (1767), s. v. “Julian the Philosopher,” decribes Constantine as a “fortunate opportunist who cared little about God and humanity” and who “bathed in the blood of his relatives.” And the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) thought that in the state-supported Christian church Constantine had created a “double-headed monster.”

Edward Gibbon, in his celebrated The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88), held that Constantine degenerated “into a cruel and dissolute monarch,” one who “could sacrifice, without reluctance, the laws of justice and the feelings of nature to the dictates either of his passions or his interest.” He also held that Constantine was indifferent to religion and that his Christian policy was motivated by purely political considerations.

In his The Age of Constantine the Great (1852) the renowned Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt saw in Constantine an essentally unreligious person, one entirely consumed by his ambition and lust for power, worse yet, a “murderous egoist” and a habitual breaker of oaths. And, according to Burckhardt, this man was in matters of religion not only inconsistent but “intentionally illogical.”

Even the great Theodor Mommsen, whose judgment is never to be dismissed lightly, expressed the opinion, in 1885, that one should speak of an age of Diocletian rather than of an age of Constantine; furthermore that the little which we can tell about Constantine’s character, between the flattery and hypocrisy of his supporters and the hateful attacks of his enemies, is not admirable.

Henri Grégoire (1881–1964), distinguished Belgian scholar, vigorously denied any conversion of Constantine in 312 and, quite unreasonably, it seems to this writer, asserted that the real champion of Christianity was Licinius.

Generally in our own century competent historians of antiquity have examined the record more objectively and reached, while not a consensus, more balanced conclusions. In the following chapters an effort will be made to present these more balanced conclusions in a concise form, or, where conclusions are not possible, the issues and problems in an unbiased manner.

Like most other books on Constantine, so the present modest study purposely places much emphasis on matters of religion. Constantine’s position as the first Christian emperor and the energy and thought which he expended on matters of religion demand this, the nature of our sources brings it about quite naturally, and most readers will expect it.

2

THE SOLDIER EMPERORS AND DIOCLETIAN

If we wish to understand the emperor Constantine we must first examine briefly the times in which he was born and raised and which left their mark upon him.

The half century which passed from the death of the emperor Severus Alexander in 235 to the accession of the emperor Diocletian in 284 presented the Roman empire with a seemingly endless series of crises and calamities, political, military, economic, and social in nature.

One clear indication of the insecurity of the times is found in the rapid succession of emperors. With predictable regularity emperor after emperor rose to the top through the ranks of the army, reigned for a short while, and died on the field of battle or fell victim to assassination. The average length of the reigns of these emperors is only three years, and none lasted for more than eight years (except that Gallienus was co-Augustus with his father Valerian in 253–60 before ruling as sole Augustus in 260–8). How many emperors there were is difficult to say with any degree of accuracy, because in addition to those who gained recognition by the senate there were numerous usurpers and contenders. All of them had risen through the ranks of the army and are, therefore, often called the soldier emperors or barrack-room emperors. Many of them, Claudius Gothicus and Aurelian for instance, were capable and energetic enough, but none was able to break the vicious cycle. At the same time the integrity of the empire was threatened by separatist movements in both West and East: the emperor Aurelian (270–5) had to overcome both a secessionist Palmyrene kingdom, under the famous Zenobia, in the East and a secessionist Gallo-Roman empire in the West.

Along the long Rhine-Danube frontier the Romans faced larger, better organized and more formidable Germanic tribes than ever before: Saxons, Franks, Alamanni, Marcomanni, Vandals, Burgundians, and Goths. Again and again one or the other of these tribes penetrated deep into Roman territory. Gaul and northern Italy suffered especially from repeated Germanic incursions; Dacia (modern-day Romania) had to be abandoned. Even the safety of the city of Rome could not be taken for granted; Aurelian’s Wall, 12 miles long and still almost encircling the heart of the city, is a monument not only to Roman engineering skills but also to Roman insecurity. In the East Sassanid Persia pursued a vigorous policy of aggression and expansion. In 260 the emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by the Persian king Shapur I at Syrian Edessa and suffered unspeakable humiliation before dying in captivity.

In circumstances such as these, it is easy to see that the need to recruit, pay and supply a large standing army took precedence over all other needs. Taxation and requisition of goods, often unfairly and inefficiently administered, imposed intolerable burdens on the civilian population and weakened the entire economy. Inflation ran rampant, and the currency was debased. Agricultural production declined as the rural population was driven by despair to abandon productive land and take flight. There was an increase in brigandage. In the towns it became increasingly difficult to get the curiales, members of the propertied class, to fill administrative posts and to assume the financial burdens which went with these posts. To add to all these woes, parts of the empire, notably North Africa and the Balkans, were visited by the plague.

It seems incongruous to the modern observer that, while the empire was thus troubled, the emperor Philip the Arab (244–9) should in 248 observe the one-thousandth anniversary of the founding of the city of Rome with extravagant and wasteful games. But the prevailing sentiment of the age was a deeply conservative one: salvation was sought not in daring innovation but in a return to traditional practices, institutions and values. It is in this context also that we must understand the anti-Christian measures ordered by the emperor Decius in 249 and by the emperor Valerian in 257. These measures, too, fell short of success and were soon abandoned.

It was finally given to the emperor Diocletian (284–305) to restore the empire, by his indefatigable efforts, to relative security and stability. Who was this remarkable man?

Diocletian, born under the name of Diocles, was a man of very humble background, as many of the soldier emperors before him had been. No longer did a humble background keep a career officer from rising to the highest ranks, ranks once the preserve of the senatorial class. And like several of the soldier emperors before him, like Decius or Claudius Gothicus for instance, he was a native of Illyricum (the Balkans). This is not a coincidence, because this region was known for its adherence to traditional Roman values, such as patriotism, discipline and piety, and for the quality of its recruits.

Diocles, the future Diocletian, was born on 22 December in 243, 244, or 245, in Salona, today a suburb of Split, on the Dalmatian coast. His family apparently was undistinguished. A dubious story even has it that his father was a freedman, or perhaps he himself was a freedman. He received only a limited education and, like so many of his countrymen, sought a career in the army. We do not know the details of this career before 284.

Numerian, son of the short-lived (282–3) emperor Carus, was from July 283 to November 284 joint emperor with his older brother Carinus; Numerian was stationed in the East and Carinus in the West. Numerian, by reason both of his youth and of his temperament, was ill-suited for the demands made upon him. It was the praetorian prefect Arrius Aper who actually controlled things, and it is he who killed Numerian at Nicomedia in the hope of succeeding to the throne himself; this Aper must have been not only a powerful but also a ruthless man, for the young man whom he dispatched was his own son-in-law. Aper’s designs did not lead to the desired end: a council of the army, meeting at Nicomedia on 20 November 284, proclaimed as the next emperor not Aper, but Diocles, then the commander of the protectores domes-tici , the “household cavalry.” As for the hapless Aper, the soldiers seized him, and Diocles killed him on the spot. But there was still the problem of Numerian’s older brother Carinus, whom the army had passed over. The armies of the two rivals met in battle in the spring of 285 at the Margus (Morava) River near Belgrade. The forces of Carinus routed those of Diocletian, but Carinus was killed in action, making the victory pointless; both armies declared for Diocles (Diocletian).

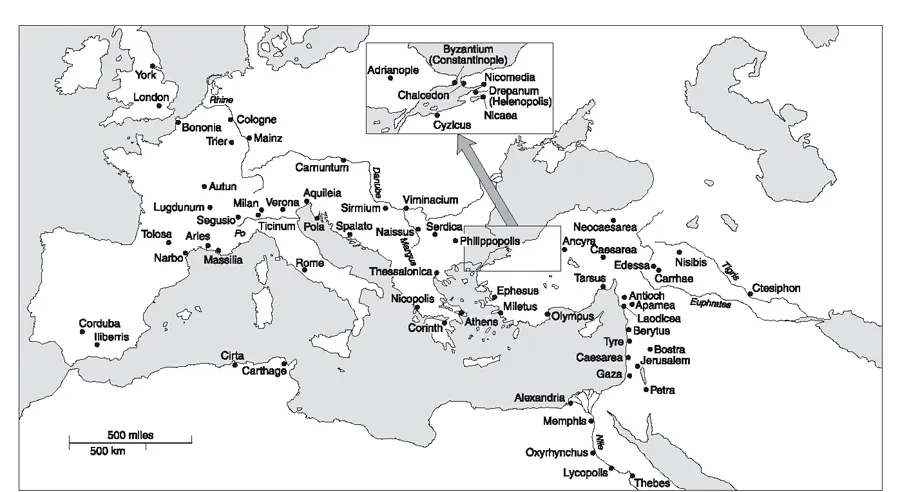

Figure 1Map of the Roman empire.

Courtesy of the Cartography Office, Department of Geography, University of Toronto.

For the Roman empire of the third century the manner in which the new emperor had risen to the very top was the norm rather than the exception. What he had done had been done many times before; what made him different from his predecessors was that he succeeded where they had failed and that he endured for more than twenty years while they had been swept away after much shorter reigns. He broke the cycle. Nor can much moral blame be attached to what he did; any other course of action might well have cost him his own life.

The new emperor took on the name of Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus and began the daunting task of restoring the empire. He, too, like the men before him, was conservative in his approach: traditional institutions were to be restored or strengthened, not replaced, and in this conservative approach religion played a major role. He was capable, confident and proud, and as a soldier he knew the value of discipline.

Early in his reign, certainly before the end of 285, Diocletian appointed a trusted comrade and fellow-Illyrian, Maximian, as Caesar and gave him responsibility for the western part of the empire, especially for the security of the Rhine frontier. Before too long, on 1 April 286, he promoted him to the rank of Augustus. Joint rule of two Augusti had been tried before, but less successfully: Marcus Aurelius had in the earlier years of his reign as his fellow-Augustus the undistinguished Lucius Verus, and Gallienus had been Augustus jointly with his father Valerian. On 1 March 293 Diocletian expanded this joint rule of two Augusti into the system now known as the Tetrarchy, or First Tetrarchy, to distinguish it from the Second Tetrarchy which existed for a short while after his retirement in 305. He did this by appointing two other Illyrians, Galerius and Constantius, as Caesars or “junior emperors.” Galerius was to serve as Caesar under Diocletian himself, and Constantius, the father of Constantine, was to serve as Caesar under Maximian. To strengthen the bonds between each Caesar and his Augustus, both Caesars were adopted by their respective Augusti; furthermore Valeria, Diocletian’s daughter, was given in marriage to Galerius, and Theodora, Maximian’s daughter (or stepdaughter, according to some sources), to Constantius.

The new system did not divide the empire. Each of the four emperors had specific responsibility, especially in matters of defence, but they were not restricted by territorial boundaries. Each Augustus supervised his own Caesar, and Diocletian remained a senior and central authority. All new legislation was issued in the name of both Augusti. The new system provided for greater efficiency in the administration of the empire and for greater security along the borders (by reducing response time). It also provided an orderly means of succession: it was anticipated that in due time the two Augusti would step down, the two Caesars would succeed them, bringing with them a wealth of experience, and they in turn would appoint new Caesars. The system was thus, in theory, self-perpetuating; it would prevent the disgraceful way in which most emperors during the third century, including Diocletian himself, had attained their position. That it worked only once certainly was not Diocletian’s fault.

Diocletian provided for a new territorial organization of the empire as well. There were now four areas of responsibility, the later prefectures: the West, Italy, Illyricum and the East. Each of these had its own capital or, more accurately, chief imperial residence: Constantius resided in Trier, Maximian in Milan, Galerius in Thessalonike, and Diocletian in Nicomedia (now Izmit). The city of Rome, although still the seat of the senate, was now of much diminished importance. The second-highest level of administration was the diocese, and there were twelve dioceses in the empire, each headed by a vicarius and each consisting of a number of provinces. By dividing existing provinces Diocletian vastly increased the number of provinces throughout the empire from about forty to more than one hundred; it has often been assumed that the aim was to reduce the possibility of rebellion. It is also noteworthy that Italy, except for the city of Rome, lost its privileged status and was divided into provinces and subjected to taxation just as the other territories of the empire were.

Diocletian and his colleagues were quite successful in their efforts to assure the integrity and security of the empire. Diocletian himself campaigned successfully on the Danube frontier and settled a revolt in Egypt. His Caesar Galerius fought successfully against the Goths on the lower Danube and, after an initial setback, won a fine victory in 298 over the Persian king Narses; the Arch of Galerius in Thessalonike bears witness of that victory to this day. Maximian secured the Danube frontier and quelled an insurrection in Mauretania. His Caesar Constantius secured the Rhine frontier and recovered Britain from the secessionist naval commander Carausius and from the usurper Allectus who succeeded him. To achieve these military successes Diocletian had vastly increased the size of the army, perhaps doubled it. He had also divided it into two branches, the mobile field army, known as the comitatenses, and the border garrison troops, known as the limitanei.

Diocletian was much less successful in his attempts to strengthen the faltering Roman economy. The burdens placed upon this economy were now heavier than ever because of the increased size of the army, an enlarged bureaucracy, and four imperial residences. An equalization of the tax assessments provided at least some relief. Diocletian’s monetary reform, undertaken in 294, was only partially successful; a currency edict in 301 represents a further effort to stabilize the monetary system. His famous Edict on Prices, also issued in 301, was an attempt to curb inflation by prescribing maximum prices for a long list of goods and services. It failed, but to historians the extant text is the single most important document of Roman economic history. In his efforts to control the economy Diocletian even used coercive measures to freeze people in their occupations, whether they be farmers or craftsmen, and in their habitats. He was, of course, no more an economist than anyone else in antiquity.

Diocletian’s desire for conformity, including religious conformity, and also political considerations led him in 302 to launch a severe persecution of the Manichees, wh...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- LANCASTER PAMPHLETS IN ANCIENT HISTORY

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CHRONOLOGY

- 1: INTRODUCTION

- 2: THE SOLDIER EMPERORS AND DIOCLETIAN

- 3: CONSTANTINE’S RISE TO POWER

- 4: CONSTANTINE’S CONVERSION

- 5: CONSTANTINE AS THE SOLE RULER OF THE WEST

- 6: THE CONFLICT WITH LICINIUS

- 7: THE ARIAN CONTROVERSY, THE COUNCIL OF NICAEA AND ITS AFTERMATH

- 8: THE CRISIS IN THE IMPERIAL FAMILY

- 9: THE NEW ROME

- 10: CONSTANTINE’S GOVERNMENT

- 11: CONSTANTINE’S FINAL YEARS, DEATH AND BURIAL

- 12: CONSTANTINE’S IMAGE IN ROMAN ART

- 13: AN ASSESSMENT

- APPENDIX I: THE SOURCES FOR THE REIGN OF CONSTANTINE

- APPENDIX II: GLOSSARY OF GREEK, LATIN AND TECHNICAL TERMS

- APPENDIX III: BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

- APPENDIX IV: THE CREEDS

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Emperor Constantine by Hans A. Pohlsander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.