Chapter 1

Introduction

What is cognition?

THE WORD “COGNITION” is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge through thought, experience and the senses”. So, cognition is an umbrella term that refers to all of the mental activities that we engage in; our thoughts and our thinking.

Thinking itself is not a simple process, or even a single process. Thinking (or cognition; the two terms are interchangeable) is a complex procedure that is made up of many other processes. Identifying the different processes that are involved in thinking about both different things and in different situations is one of the main aims of those studying cognition. This is not an easy task, as we can’t actually observe thoughts. We can only observe the behaviours and actions that result from them and the brain function that accompanies them.

Before we can engage in any actual thinking we need to have something to think about. Thinking involves the processing of information and therefore we need information before any processing can occur. Some theorists suggest that we are born with some innate knowledge, but much of our knowledge comes about as a result of learning. To learn things we need to interact with our environment and commit our experiences to memory. Things that we have experienced in the past are stored in our long-term memory. Some theorists argue that all our experiences are committed to memory; other theorists disagree and suggest that only a proportion of our experiences are stored in memory. This is a contentious issue that we do not need to consider here. Either way, we often call on the information that we have stored in our memory; our knowledge. Sometimes we reminisce about specific events or experiences just because we want to or because we want to tell other people about them. At other times we use our past experiences to help us interpret the situation that we now face. This is all thinking and it is this that will be the focus of this book.

When we have no previous experiences or knowledge relevant to the task at hand, we have to work with the information that is currently available. In such situations the only information that we can process is the information that our senses are receiving at the time. Although there is a lot of controversy about whether we have different types of memory and what these might be, it is generally accepted that information that is being received and attended to is held in our working memory and that this is distinct from long-term memory. Information that is recalled from long-term memory when needed to deal with a cognitive task is also stored in our working memory during the time that it is being processed. When thinking we often integrate environmental information and information that we have previously stored in our long-term memory in this way.

All of the knowledge that we have and use when thinking is represented in our brains in some form. The pieces of information that we manipulate when thinking are therefore known as representations. We can represent information at different levels. Whereas most of what we think of as knowledge we can access voluntarily and on a conscious level, some knowledge is stored at a level that precludes its availability to consciousness. Reflex behaviours are an example of lower-level representations of this sort. Sometimes we do things in response to environmental stimuli seemingly without thinking or, to use the proper term, automatically, because we are not consciously aware of any knowledge being involved. For instance, the other day someone asked me which of my kitchen taps was cold and which was hot. I use these taps on a daily basis and consistently turn on the one that will provide me with the temperature water I require. Despite this, it took me a long time to answer the question, as I hadn’t really thought about knowing this before, although I obviously do. This is because I had stored the information at a behavioural level, something that was further evidenced by the fact that I had to visualise getting a glass of cold water and act out my actions to answer the question. Automatic responses are very similar to reflex behaviours in a way because in both cases we act upon knowledge as to how to behave in response to a particular environmental cue. The difference between the two is that reflex behaviours are innately preprogrammed whereas automatic behaviours have been learned, albeit subconsciously.

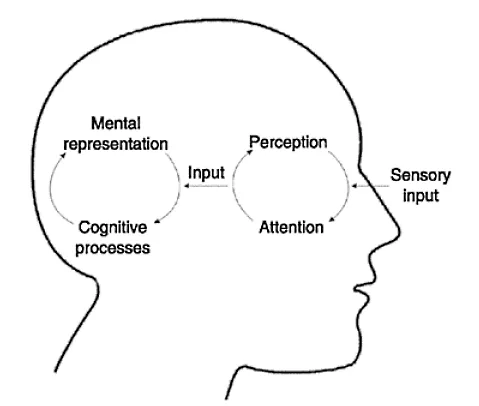

Before we can form representations of our experiences we obviously need to experience things. Experience depends upon us both perceiving and attending to the information that we receive when we interact with our environment (Figure 1.1). Our senses pick up a lot of information and we often need to interpret this. The interpretation of raw sensory input involves imposing some sort of order upon what might otherwise be a confusing bombardment of information. The actual sensory input that we receive is fairly chaotic. As we move around our world we experience a constantly changing array of sights, sounds, smells, feelings and tastes. To make any sense of this we need to organise things. For example, we need to identify objects as objects and therefore we need to work out which features “go together” and form whole objects as distinct from other objects. We also need to understand that the same objects can give rise to several different types of sensory input, and we need to know how these relate to each other. For example, we can see, hear, smell, taste, and feel a bowl of Rice Krispies™ and we integrate this knowledge into an experience. We do not experience the different bits separately. Given that these abilities seem fundamental to the formation of complete and accurate representations it seems likely that we would be able to interpret sensory input at an early age. We might even be preprogrammed to be able to do such things from birth (we will return to this issue in Chapter 2).

Figure 1.1 The relationship between sensory input and information processing

Having imposed order upon sensory input we then need to attend to it. Even though we may recognise many objects in our surrounding environment as objects, we don’t always pay attention to all of them! Although our attention can be focused intentionally, that is we can consciously control it, we also attend to a lot of things that we are not consciously aware of paying attention to. Our understanding of this aspect of cognition underlies things such as television reconstructions of crimes. Often we attend to information without knowing it and triggers are needed to bring that information to a consciously accessible level. After all, we can’t deliberately recall things that we don’t know we know.

Attending to information on some level, whether that is consciously or subconsciously, is necessary for information to be committed to memory. As previously mentioned, our working memory is where much of our cognition occurs. When we are actively thinking about something, whether that be recalling a memory or solving a problem, it is our working memory that is being used. If a cognitive process, such as using a strategy to solve a problem or to remember something, is applied to information in working memory this often triggers its transference to our long-term memory store. Whether this is always the case is debated but evidence suggests that it does help.

The simple retrieval of a previously stored memory can be said to constitute thinking at a low level (for example, recalling the events of a Friday night out involves thinking about what happened) but we often go beyond the information given and fill in gaps and Introduction 3 interpret events. Such interpretation often involves us making use of information that we have previously acquired and stored in our long-term memories. For example, the way in which we interpret the behaviour of another person will depend on our knowledge of that person. Similarly, our knowledge about an individual will be based on similarities in that person’s behaviour over time and in different circumstances. This is a much more complex process than the retrieval of memories because it involves both this and the integration of this knowledge with new knowledge, and thus it involves more information processing. As such, it is considered to be a higher-order process. The passage of information from our working to long-term memory is therefore two way. We often use knowledge we already have to interpret new information. Similarly, new information can help us to make sense of and organise memories that we have previously acquired. Given that we hold a lot of information in our long-term memories and that we often need to access this information at a moment’s notice (and that we can do this quite easily) it is probable that we organise our long-term memories; that we have some sort of mental filing system.

Thinking is not just a matter of remembering and recalling information, as we have seen. We often have to go beyond what is given and engage in some sort of reasoning process. Such reasoning allows us to make use of information and generate new ideas based on information we have acquired elsewhere. All the cognitive activities that we engage in are geared towards obtaining information, understanding and interpreting this information and modifying our existing knowledge on the basis of new information so that it provides an accurate description of objects and explanation for events that happen in the outside world. That is, we appear to be preprogrammed to learn and develop our knowledge. Only this flexibility of thought appears to distinguish us from other species and allow for the complexity and ever-changing nature of human society. Human cognition involves a constant interaction between incoming information and information that we have already stored away in our long-term memory. The process of using old information to interpret incoming information often results in changes being made to the knowledge stored in our long-term memory. This allows for cognitive development, something that appears to be a more complex and lengthy process in humans than in other species.

Individual differences in cognitive development

If cognition is thinking, then the term cognitive development refers to the way in which our thinking changes with age. Given that we appear to be internally motivated to learn, and that human cognition is flexible and develops in response to environmental experiences, it would seem obvious that every individual, because of their different experiences, will follow a different developmental pattern.

All children are different from the outset. Any parent of more than one child will tell you that they have different temperaments and that these are apparent very soon or even before birth. Such temperamental differences are a reflection of genetic tendencies and are therefore inherited.1 The temperamental differences of children affect cognitive development in that they specify how the child interacts with his or her environment. They also affect the way in which the environment responds to the child. For example, an active baby might receive more stimulation from his or her caregivers than a baby who cries a lot, who might elicit more negative responses. Given that environmental input and experience is where much of our knowledge comes from, any differences in experience will effect the cognitive development of the child. Other factors that affect experience, such as cross- and within-cultural differences in childrearing and expectations of development, all have an impact upon the precise path of development. We will discuss this issue in more depth later in this book.

Despite individual differences in development, development does seem to follow a predetermined path, with children reaching specific developmental milestones at remarkably similar ages, both across and between cultures. Because of this, the focus of this book will be on the process of normal development and general trends and changes in cognitive abilities. However, factors that contribute to individual differences in development will not be glossed over completely because they can often help us to identify factors that contribute to development.

Cognitive development

It is obvious that newborn infants are not capable of complex thought patterns but also that they are born with the capacity to develop the ability for complex thought. This ability appears to be a uniquely human capacity.2 Newborn babies appear to be equipped with all that they need to be able to learn. They enter the world ready and able to extract information from their environment and thus they can immediately begin to form representations of this information (these abilities will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter). But development involves more than just collecting pieces of information. Whereas learning itself can be a passive process, the learner merely taking “photo-shots” of reality and committing them to memory, for humans at least cognitive development goes way beyond this. Human cognition is an active process that involves interpretation and organisation so as to provide an explanation for, and interpretation of, what is seen to be reality. As such, cognitive development involves the constant reorganisation of knowledge so that new incoming information is consistent with what the learner already knows. This has the knock-on effect of enabling the learner to develop new and more effective ways of dealing with and explaining the world.

It is not only the amount of information that we have learned (and have stored in our memory) that increases with age. The degree to which it can be and is consciously accessed and controlled also changes with development. Thinking does not just get better, faster and more efficient with age, the processes involved actually change in nature. Moreover, the way in which information is represented changes as we develop.

Why study cognitive development?

Understanding the nature of cognitive development, the factors that contribute to it and the way in which internal and external factors interact and result in changes to the way that children think, allows us to develop ways of teaching children so that their development is maximised. Similarly, knowing what constitutes typical cognitive development allows us to identify those children who are not developing as expected. We can then use our knowledge of development to help the child development as best we can. For example, if a child’s reading age is below normal we can look at the environmental and biological factors that we know contribute to reading development (assuming that it is only the child’s reading that is affected). We know that certain brain regions are implicated in reading and so these might be damaged. If this is the case then we might be able to develop strategies that do not rely on these parts of the brain but would enable the child to develop reading abilities. We also know that motivation to learn and the encouragement of caregivers and access to reading materials are important factors in the development of reading abilities. If these appear to be contributing to the problems being experienced by the child then we could take the appropriate steps and try and remedy the situation (we will discuss reading development in much more detail in Chapter 6).

If the factors that contribute to development in a particular area are biologically or genetically determined, the extent to which we can intervene in development is obviously going to be limited. This is often the case with children who have genetic syndromes such as Down syndrome, which put an upper limit on cognitive development. Despite these limitations, we can aim to maximise development and make sure that children fulfil their biologically limited potential. The study of genetic syndromes can be helpful in informing our understanding of cognitive development. If a specific biological impairment can be associated with specific cognitive impairments then we have evidence to suggest that biological mechanisms have a large part to play in cognitive functioning in the impaired area. We will discuss how studies of brain function can help our understanding of cognitive development later in this chapter.

Developmental psychologists study cognitive development to understand it. The theoretical models and research findings that have contributed to and arise from such an understanding also have a lot of practical value for educators and clinical child psychologists. Likewise, studies that look at the effects of intervention programmes that have been developed from theories of development can provide useful feedback and inform subsequent theories and models. The relationship between theory and practice is therefore two way and continuous.

Traditional approaches to the study of cognitive development

Traditionally, the behaviourist school of thought argued that children came into the world with no knowledge or capabilities, except the ability to learn. “Blank slate” theories such as this see development as little more than the gradual acquisition of knowledge; the child simply receives input from the external environment and internalises it. The nativist view, by contrast, argued that we are born with innate abilities that are preprogrammed into the brain at birth and so determine development. For proponents of this approach, the environment of the child has little effect on the child’s cognitive development as it is therefore thought to be dictated by a biological timetable within which there is little room for manoeuvre; a view known as genetic determinism.

Both the nativist and behaviourist accounts of development described children as passive participants in the process of development; they are either entirely at the mercy of their biology (the nativist view) or dependent on what they are taught (the behaviourist view). Neither of these is correct. We now know that environmental and biological factors interact and the child has an active role to play in his or her own development. This is a constructivist position and it is the constructivist perspective that Jean Piaget pioneered.

Many consider Piaget to be the founder of developmental psychology because he was the first to suggest that children of different ages think in different ways. This sounds obvious today, but for many years it was assumed that children think in the same way as adults—they are just not as good at it. Piaget’s theory acknowledged that both innate predispositions and environmental factors have a role to play in cognitive development. Piaget believed that children’s thinking is constrained by brain development and tendencies rooted in the child’s biological make-up and that these put an upper limit on the child’s cognitive capabilities. However, he also suggested that the information that the child is presented with, as well as the way in which it is presented, affects the child’s thinking and how this thinking develops. Thus he acknowledged the role of the environment. Piaget’s theory represents a compromise between the radical nativist and behaviourist theories and suggests that cognitive development is transactional, that is, that it results from an interaction between environmental input and knowledge and structures that are inside the child. Piaget claimed that children are preprogrammed not only to learn, but also to organise their mental representations and to adapt their existing knowledge base on the basis of new information; that children actively construct knowledge.

Piaget saw the process of development as a continuous one with new cognitive developments emerging from earlier ones. Piaget claimed that children are born with only a very limited amount of knowledge. This knowledge is said to be behavioural in nature and therefore it is not available to consciousness. What he meant by this is that newborn infants possess only knowledge of how to do certain things such as demonstrate simple reflex behaviours in response to specific features in the environment. They are not aware that they have such k...