eBook - ePub

Attachment and Family Systems

Conceptual, Empirical and Therapeutic Relatedness

This is a test

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Attachment and Family Systems

Conceptual, Empirical and Therapeutic Relatedness

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

I Attachment and Family Systems is a cogent and compelling text addressing the undeniable overlap between two systems of thought that deal with the nature of interpersonal relationships and how these impact functioning. In this enlightening work, leading thinkers in the field apply attachment theory within a systemic framework to a variety of life cycle transitional tasks and clinical issues.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Attachment and Family Systems by Phyllis Erdman, Tom Caffery, Phyllis Erdman, Tom Caffery in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theoretical Overview

Chapter 1

Implications of Attachment Research for the Field of Family Therapy

A central feature of my concept of parenting [is] the provision by both parents of a secure base from which a child or and adolescent can make sorties into the outside world and to which he can return knowing for sure that he will be welcomed when he gets there, nourished physically and emotionally, comforted if distressed, reassured if frightened. In essence this role is one of being available, ready to respond when called upon to encourage and perhaps assist, but to intervene only when clearly necessary.

—John Bowlby, MD, A Secure Base: Parent–Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development

Over the past 15 years, there has been increasing interest in integrating the field of attachment theory and research with clinical assessment and intervention (e.g., Fonagy, 1999; Marvin, 1992; Marvin, Cooper, Hoffman, & Powell, 2000; Van den Boom, 1995; Lieberman & Zeanah, 1999). The two areas of clinical intervention most focused on are object relations therapy (Fonagy, 1999) and family rherapy (Marvin & Stewart, 1990; Byng-Hall, 1999). Both of these movements are in their preliminary stages, and both offer much promise. In the case of attachment research and family therapy, the excitement and motivation seem to be coming primarily from the family therapists.

In writing this chapter I have three main goals. First, I want to present a view of attachment theory and research from the perspective of a family researcher and family therapist. This will be a very personal view, somewhat different in focus from the work of most current attachment researchers. This personal view stems primarily from (a) my longstanding interest in the systemic nature of attachment theory, (b) the fact that my clinical orientation has always been a family systems model, and (c) my active involvement in developing attachment-based interventions for at-risk children and their families. My impression is that most practicing clinicians have an understanding of attachment theory and research that is limited to the individual child, or at most the child–parent dyad, rather than to the child or dyad as a subsystem of the larger family system. This limitation is understandable because most current research on attachment is focused on the child, or at most the child–parent dyad.

My second goal is to present examples, from the research and clinical work of my colleagues and myself, of interventions that do integrate these two fields. Third, I will end the chapter with some thoughts about future directions. As will become obvious, I do think an integration of attachment and family systems is both possible and promising. I also think, however, that the integration will require specialized tools and specialized training or collaboration. Although the school of family therapy I will focus on here is structural family therapy, I think the integration applies equally well to others, such as the “constructivist” and “psychoanalytic” schools of family therapy.

Attachment Theory and Family Systems Theory: Points of Convergence and Divergence

Interestingly, the founder of attachment theory himself, John Bowlby, always espoused a family systems perspective. From early in his career, Bowlby was struck with the fact that children develop within an extended family system and that our understanding of relationship problems and our interventions should be viewed from that perspective. In fact, Bowlby (1949) wrote one of the first papers on family therapy. In it he suggested that the problems child guidance clinics faced actually reflected tensions with the overall family, that even very dysfunctional families have a strong drive to live together in a healthy way, and that working jointly with all family members was a procedure that held considerable hopes for successful intervention.

What turns out to be Bowlby’s most important contribution was his desire to study these relationship problems within a truly scientific, empirical framework. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Bowlby thought that family systems were too complex to study with the scientific methods then available, and he decided to take just the first step in this process (i.e., the study of parent–child dyadic relationships as a subset of larger family systems). Bowlby went on to develop the theory, and the Robinsons, H. R. Schaffer, Mary Ainsworth, and others provided the initial empirical validation for the theory.

Although Bowlby did not highly develop that part of his theory that would apply to family systems, systems theory was one of the two primary theories Bowlby used in developing attachment theory—the other being the field of ethology. In fact, he drew heavily from general systems theory, information theory, and cybernetics in developing what he eventually called his “Control Systems Theory of Attachment.” Finally, toward the end of his life, Bowlby (1988) again placed strong emphasis on the child as developing within the family system and called for research on that topic.

To my knowledge, it was Patricia Minuchin (1985) and Marvin and Stewart (1990) who first argued that the two fields could benefit by an integration. A quick review of these papers suggests points of similarity and of difference. What has always been intriguing to me is that the two frameworks do not appear to have contradictory basic theoretical assumptions. To the extent this is true, it implies that an integration that does not violate the tenets of either theory is possible.

Systemic Similarities

From P. Minuchin (1985) and Marvin and Stewart (1990), both theories share the following basic ideas:

- Any system is an organized whole, and elements within the system are necessarily interdependent. This applies equally, and in the same manner, to triadic mother–father–child roles within the family, to the reciprocal behaviors of caregiver and child, and to components of the child himself1 (e.g., its attachment and its exploratory behavior systems).

- Complex systems are composed of systems and subsystems. This nested set of systems is equally applicable to the child-as-system or to the family-as-system. The subsystems within a larger system are separated by boundaries, and the interactions across boundaries are governed by implicit rules and patterns. Dysfunction within the system is often the result of the breakdown in the adaptive rules governing those boundaries.

- Behavior patterns in a system are circular rather than linear. This forces us to assume a much more complex model of the factors that activate and terminate different behavior patterns. Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) and family systems theory (P. Minuchin, 1985) have similar frameworks for conceptualizing these factors—both based largely on information theory, broadly defined.

- Systems have homeostatic, or self-regulatory, features that maintain the stability of certain invariant patterns or outcomes. This is true whether we are speaking of a dysfunctional pattern of boundary violation within a family system or the basic operation of the young child’s use of the attachment figure as a secure base for exploration.

- Evolution and “developmental” self-(re)organization are inherent to open systems. Children’s attachment behaviors, as well as family structures, undergo developmental changes according to many of the same underlying developmental processes.

The systemic similarities between the two frameworks also include the fact that interactions between and among individuals are as much a focus of observation and conceptualization as the behaviors of the individuals themselves. They also include a focus on lifespan developmental changes in the overall family system coinciding with developmental changes in the child or sibling subsystem. Finally, they include the recognition of the child’s role in organizing family interaction patterns, as well as the child himself being organized by family patterns.

Systemic Differences

Although there are differences in the two frameworks, I maintain that these differences are more those of focus and emphasis rather than of substance. For example, attachment research has focused primarily on the structure and functioning of affectional bonds. Family systems work has focused primarily on family subsystems, boundaries, roles, hierarchical relations, communication and conflict-resolution, and homeostasis and change. Certainly, both fields acknowledge the importance of the other’s focus, both are increasingly moving in the other’s direction, and both would profit from more integration. Fifteen years ago, the two frameworks had markedly different focuses: Attachment research started with the individual child and caregiver and worked toward the dyad-as-system. Family therapy and research, conversely, started with a focus on triads or larger systems and subsystems (see Bowen’s work). In recent years, however, there is as much movement in family systems thinking toward a focus on individual family members as there is in attachment research toward a focus on triads.

Attachment Theory from the Perspective of a Family Systems Therapist

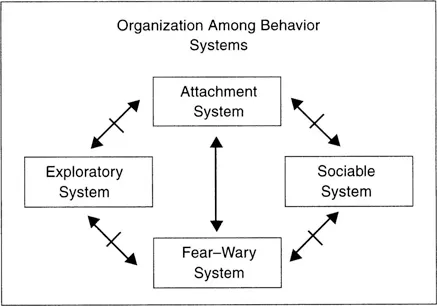

Bowlby (e.g., 1969) and Ainsworth (e.g., 1990) thought of attachment behavior as belonging to a coherent system of behaviors that have the predictable outcome of bringing the youngster and caregiver into proximity and contact with one another. The attachment behavior system has an internal organization of thoughts, feelings, plans, and goals (internal working models) and has the biological function of protecting children from a wide range of dangers while they are developing the skills to protect themselves. Attachment researchers are especially interested in three additional behavior systems that operate in a dynamic equilibrium with the attachment system (e.g., Ainsworth, 1969, 1990; Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). These other systems are the exploratory system, the wary–fear system, and the affiliative, or sociable, system. In a self-regulatory manner family systems therapists can immediately appreciate, these four behavior systems activate and terminate each other in a way that protects the child by inhibiting the exploratory and sociable systems and activating the attachment system when distressed or afraid, and then facilitates the child’s developing competence by activating its exploratory and sociable systems when its wary or attachment systems are not activated (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Organization among behavior systems.

Ainsworth (e.g., Ainsworth, 1967; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978) identified this complex, cyclical pattern of behavior as using the attachment figure as a secure base for exploration. When it is functioning properly, this attachment provides the child with a sense of emotional comfort and security in knowing that he can move off from the attachment figure to explore and that the attachment figure will be available for protection and assistance if necessary. This is the “basic trust” that Erik Erikson spoke of so many years ago, and it provides the youngster with an internal, developmental foundation of seeing others as loving, and seeing himself as lovable.

An attachment is part of one form of “affectional bond.” An affectional bond is a relatively long-enduring tie in which the partners are important to one another as unique individuals who are not interchangeable with others. As the term implies, these bonds are partially governed by strong affect and have the tendency to bring the partners together—either physically or in some form of communication—with regularity. In the case of the attachment bond, this is especially true when one partner or the other senses some danger. Some other affectional bonds include the caregiving bond (the other side of an attachment), sibling bonds, sexual pair bonds, peer or friendship bonds, and mentor or teacher bonds.

The Attachment–Caregiving Systemic “Dance”

What really brings attachment theory and family systems theory together is this notion of a bond, which itself conceptually demands the interactions of at least two partners. From the beginning of his work, Bowlby insisted that an attachment cannot exist, or be understood, outside of the interactions and relationship with the partner who has a reciprocal caregiving bond with the child. Like the child’s attachment behavior system, the parent’s caregiving behavioral system also has an internal and external organization, with the biological function of protecting the infant or child (e.g., Marvin & Britner, 1995; Solomon & George, 1999). To me the most exciting aspect of Bowlby’s (1969) first volume in his trilogy on attachment is his detailed, clear, and wonderfully systemic descriptions of how the young child’s attachment behavior system and the parent’s caregiving system activate and terminate each other in an intricate “dance” on a minute-to-minute basis over the course of a day, and how this “dance” changes and adapts over time as the child develops or as the circumstances (e.g., risk conditions) in which the family lives change. As so aptly described by family systems theorists, it is often difficult to tell who is “leading” the dance, and who is “following.”

Ainsworth observed this “dance” taking place naturalistically in her observational studies of parent–infant interaction in Uganda (e.g., Ainsworth, 1967), in Baltimore (e.g., Stayton, Ainsworth, & Main, 1973), and under standardized, laboratory conditions in the “Strange Situation” (e.g., Ainsworth et al., 1978). The descriptive framework for which she is so renowned focused on the child’s contribution to the pattern of attachment–caregiving interaction. Most of her published statements on the caregiver’s contribution to the patterns were in the form of rating scales. Her students’ and her written descriptions of the caregiver behavior that led to those ratings, however, are rich descriptions for understanding the complex patterns of interaction. Along with Bowlby’s theory, these descriptions have led some attachment researchers to describe the caregiver’s contribution to the interaction and the caregiver’s internal working models (IWMs) of the relationship in a manner that really begins to describe systemic (at least at a dyadic level) patterns of interaction (Marvin & Britner, 1995; George & Solomon, 1996).

Because it is so widely used, and especially because it is so standardized across the infancy and preschool years, describing the attachment–caregiving behaviors in the Strange Situation offers an excellent opportunity to illustrate this systemic interaction. A mother carries her two-year-old son, Jochen, into a 15’ x 15’ room with some chairs, toys on the floor, and a one-way window through which the situation is being videotaped. She puts the toddler down among the toys, and she sits in one of the chairs. Jochen watches closely as his mother sits and smiles at her when he realizes she is not going to move off. His attachment behavior then terminates and his exploratory behavior becomes activated as he turns and begins exploring the toys, using her as a secure base for exploration. Mother watches as he plays, occasionally smiling with mild but obvious delight at his activity. Her caregiving system is “on,” but she sees no reason to intervene and therefore merely monitors Jochen’s play, available to him should he need her. For three minutes (the length of this first episode) Jochen plays, occasionally looking at his mother, showing her the toy with which he is currently playing, and naming the toy or making some other brief comment.

After three minutes a friendly adult enters the room, introduces herself, sits quietly for a few moments, and then begins a conversation with the mother. As the stranger enters the room and sits, Jochen’s wary system is activated. As represented in Figure 1, this automatically terminates his exploration and mi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Part I: Theoretical Overview

- Part II: Family Perspective

- Part III: Life Cycle Transitions: Child and Adolescent Perspective

- Part IV: Life Cycle Transitions: Adult Perspective

- Part V: Specific Clinical Issues

- Index