eBook - ePub

The Cultural Role of Architecture

Contemporary and Historical Perspectives

This is a test

- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Cultural Role of Architecture

Contemporary and Historical Perspectives

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Exploring the ambiguities of how we define the word 'culture' in our global society, this book identifies its imprint on architectural ideas. It examines the historical role of the cultural in architectural production and expression, looking at meaning and communication, tracing the formations of cultural identities.

Chapters written by international academics in history, theory and philosophy of architecture, examine how different modes of representation throughout history have drawn profound meanings from cultural practices and beliefs. These are as diverse as the designs they inspire and include religious, mythic, poetic, political, and philosophical references.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Cultural Role of Architecture by Paul Emmons,Jane Lomholt,John Shannon Hendrix in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Part One Architecture as

Agent of Recovery

Agent of Recovery

A Testimony to Values

Introduction to Part One

Jane Lomholt

Part One examines how different modes of representation throughout history — in architecture, landscape architecture and interior design — have drawn profound meanings from cultural practices and beliefs. These are as diverse as the works they inspire and include religious, mythic, poetic, political, and philosophical references. The individual chapters examine specific architectural projects and their motivations, all, with one exception, executed before the twentieth century. Although the chapters encompass a wide range of contextual variety and cultural understanding, they have in common a tight knit specificity of focus and singularity of purpose.

As we stand now at the beginning of the twenty-first century and look back over the vast territory called history, we can perhaps identify with Walter Benjamin's Angel of History. There he is, “eyes are open wide, his mouth stands open, and his wings are outstretched. His face is turned towards the past” because that is where “history” is located. What he sees, Benjamin continues, is a major catastrophe, the fallout of which keeps piling up before him. But we have chosen to pick over some of the rubble of the past, to turn the catastrophe which has led to the present turmoil, into tools for recovery of what has been scrambled and lost, to gain an understanding of the significance of past practices, dreams, meanings and acts. So whereas Benjamin's Angel is a gloomy one, ours is one of mediation and reaffirmation of cultural awareness. We cannot go back, as the wind from Paradise pushes us relentlessly into the future, but we can learn from what we find and aim to redefine the values that our future architecture will embody.

Dagmar Motycka Weston's Chapter 1, “Greek Theatre as an Embodiment of Cultural Meaning,” introduces this part. It springs from her conviction that physical and cultural context are integral to significant architecture. Her focus is the classical Greek theatre which, she indicates (with reference to Karsten Harries), allows a people to “understand their own situation in the world through the expression of a shared ethos.” She examines the precursor of theatre, the sacred threshing floor on which circular dances were performed, and establishes a connection between the “grain-mother goddess” (cyclical renewal) and Dionysos (regeneration through fertility). Studying the fourth-century theatre at Epidaurus, she perceives the building's geometrical form as a microcosm of the Greek world.

Chris Siwicki looks at the ancient Roman world in Chapter 2, “The Restoration of the Hut of Romulus.” His focus is the hut of Romulus, which, between the third century BC and the fourth century AD, was ritually maintained in its archaic form. Although the hut may have had significance as a symbol of the city's origins, Siwicki suggests that there may have been other factors involved in its retention as a primitive structure. Ancient authors attribute other values to it, namely, that it was an example of Rome's material and moral origins.

In Chapter 3, Liana De Girolami Cheney moves to the Florentine Cinquecento in order to explore “Il Corridoio Vasariano: A Resplendent Passage to Medici and Vasari's Grandeur.” Cheney demonstrates that this audacious structure, the corridoio, which crosses the Arno above the Ponte Vecchio, expresses political power of the Medici and Vasari's “personal affirmation as a courtly artist and architect.” Under Cheney's guidance, the corridoio brings together Vasari's speculations about physical and metaphysical architecture: the passage is designed as a gallery for famous artists' self-portraits. But equally significant, she demonstrates the political power of Vasari's intricate urban composition of elements, based on early Roman symbols, for Cosimo I de Medici.

In Chapter 4, “Language Beyond Metaphor: The Structural Symbolism of Borromini's Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza,” Noé Badillo explores the Solomonic and Kabalistic connections of Borromini's church in Rome, in which language has become “the physical and metaphysical structure of the cosmos,” reflecting his understanding of the “divine nature of the universe”. Badillo emphasizes the close academic relationship that exists between Borromini and Athanaseus Kircher at the level of both philosophy and science (the study of acoustics) and that the arcane is a tacit leitmotif in the work of both men.

Jane Lomholt and Louise Pelletier locate themselves in the cultural tropes of the eighteenth century. Chapter 5, Lomholt's “Villa Albani: Repository of Multiple Narratives,” is set in the physical reality of Rome, while Pelletier's Chapter 6, “The Space of Fiction: On the Cultural Relevance of Architecture,” uses the set of a house in Paris that exists in the fiction of Jean-Fran?s Bastide (The Little House) and the architectural theories of Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières in his The Genius of Architecture. Both Lomholt's Villa and Pelletier's “little house” are described as places of seduction. Lomholt takes the reader on a walk through the gardens and buildings of Villa Albani as she remembers them. She then reconstructs the Villa and the life that was lived there in the years of its gradual completion, while examining evidence relating to authorship, doubts and uncertainties that surround its coming into being. Central to her text is the complex relationship between the Villa's owner, Cardinal Alessandro Albani, and his protégé, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, ultimately interpreting the Villa, perhaps, as a memorial and tribute to them both. It is reality with an air of fiction. Pelletier, on the other hand, examines her “little house” in the context of sensuality and the emotions in French fiction and architectural theory, especially as forwarded by Le Camus de Mézières. She concludes that he, like many of his contemporaries, developed a “spatial perception” that was based, like narrative fiction, on “a beginning, an emotional climax and an ending that resolved the dramatic tension,” endorsing fiction as “an appropriate realm of experimentation.”

The notion of fiction and narrative continues in Cristina González-Longo's Chapter 7, “Using Old Stuff and Thinking in a New Way: Material Culture, Conservation and Fashion in Architecture,” albeit in the form of “fictitious divisions” and the narratives of buildings undergoing change in their structure and usage. This chapter also brings this section of the book back to the beginning, with discussions about cultural meanings and the historical role of conservation over time. González-Longo in particular examines Palazzo Barbarano in Vicenza, Palazzo Barberini in Rome and Holyrood in Edinburgh. Her final focus is Queensberry House, Edinburgh, and its ultimate inclusion in the new Scottish Parliament. González-Longo finds that there is no universal solution to how these changes are carried out, and like Weston, she concludes that physical and cultural context are deciding factors in the reuse of (significant) existing buildings.

Chapter 1

Greek Theatre as

an Embodiment of

Cultural Meaning

an Embodiment of

Cultural Meaning

Dagmar Motycka Weston

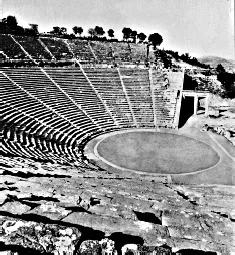

Significant architecture has always been the deep expression of a physical and cultural context, providing a living setting for human activities, and a durable embodiment for cultural meaning. The architecture of the medieval civic square or cathedral, for example, supplied existential orientation to the community. It enabled the town's inhabitants — to paraphrase Karsten Harries (1997: vii, 4) — to understand their own situation in the world through the expression of a shared ethos and to dwell within it. Analogical thinking and metaphor play a key role in this. To explore this cultural role of architecture, my focus here will be on classical Greek theatre. Theatre is a complex social phenomenon, inviting participation and often acting as an immediate expression of the spiritual aspirations and philosophical preoccupations of the society which has produced it. This was so particularly in classical Greece, with its reverence for an ethical order, and at a time when the traditional mythical understanding of the world first began to be informed by a new kind of philosophical questioning and by the social order of the polis. I shall examine some of the aspects of the role played by theatre in the context of Greek culture, thought and religion, and then focus on the fourth-century BC theatre of Epidauros (Figures 1.1a, 1.1b).

Arising from the primal ritual of appeasement of the cyclical powers of nature upon which humankind depended for its survival, and developing into worship of the god of wine and fertility, Dionysos, theatre was a sacred institution of great significance for Greek society. A religious ceremony, the theatrical performance was based on ancient myth, the heroic sagas which the Greeks considered to be their own early history. The myths were accounts of often apparently random events and conflicting forces affecting human life, representing mankind's profound attempt to understand and come to terms with an unpredictable world and its own role in it. However, classical tragedy, as we know it from the surviving works of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, is also a philosophical construct, based on the raw material

Figure 1.1a

Theatre of Epidaurus, c. 360 BC

Theatre of Epidaurus, c. 360 BC

Figure 1.1b

Theatre spectators, after a vase painting by Sophilus, c. 580–570 BC

Theatre spectators, after a vase painting by Sophilus, c. 580–570 BC

of myths, but providing a coherent understanding of the ethical principles which the Greeks believed governed the universe (Vernant and Vidal-Naquet 1988: 7). It reveals a basic belief in reason (logos), and the need to find order in apparent chaos, a propensity which characterizes mature theatre architecture.

In contrast to modern scientific society, which tends to see things in a narrowly literal and univocal way, the ancient Greeks understood all aspects of their world as being infused with a rich multiplicity of analogical meaning (see Harries 1997: 132; McEwan 1993: 62). They, for example, anthropomorphized the deities in their myths, attributing to them complex characteristics and histories, organizing them into human-like families. This tendency is also evident in the notion of mimesis (which can mean the impersonation of something other than oneself), which prompted the development of early drama.

Cosmos — the Polis — Theatre

Implicit in the cosmic significance of the theatre is also the analogy between the ordered universe of the creator, the cosmos, and its microcosm, the social structure of men, the polis. Thus the periodic ritual re-enactment of original events suggests a reiteration of creation and the renewal of cosmic order. The self-governing community which was the polis came of age in the fifth century BC. It embraced the political, cultural, moral and economic dimensions of the life of its community (see McEwan 1993; Hansen 2006). While limited primarily to those free, male householders who could become citizens, the social order of the polis was remarkably progressive and democratic for its time. Religious and political thinking were here particularly closely entwined, with the Olympian gods, who had presided over the formation of the polis, seen as keen defenders of justice and the ethical order of men. Just and ordered human society was understood as a reflection of the harmonious, ideal structure of the macrocosm. These often became the themes of tragic drama. The dramatic festivals, with their companion activity, the athletic games, were for the Greeks then much more than mere entertainment. Performed in the sacred precincts as seasonal contests in honour of the gods (agon), and comprising also sacrifice and feasting, the athletic and dramatic competitions sought to promote human excellence and the cultivation of virtue...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Cultivating Architecture

- Part One Architecture as Agent of Recovery: A Testimony to Values

- Part Two Architecture as Substance and Sustenance: Cultural Desires and Needs

- Part Three A Time of Aspirations: Cultural Understanding of the Roles of Architecture

- Index