This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Building Change investigates the shifting relationships between power, space and architecture in a world where a number of subjected people are reasserting their political and cultural agency. To explore these changes, the book describes and analyzes four recent building projects embedded in complex and diverse historical, political, cultural and spatial circumstances. The projects yield a range of insights for revitalizing the role of architecture as an engaged cultural and spatial practice.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Building Change by Lisa Findley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Power, Space and Architecture

It is no coincidence that one of the most enduring ancient stories about human hubris in the face of power is about building. In constructing the Tower of Babel, humanity, united in language and purpose, set out to build their own addition to creation: a tower to heaven. In this way they could join God in His aerial perspective of the world. The story, from the eleventh chapter of Genesis, goes like this:

And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and lime had they for mortar. And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth. And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the Lord said, Behold, the people are one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

(King James Version)

God, apparently jealous, watched as humanity began to build a tower at Shinar. He was infuriated by this effort, sure that these humans would attempt further acts of arrogant defiance. So God invented myriad languages, dividing them among the builders so they could not understand each other, and therefore could not communicate to complete the tower. One can imagine the chaos on the building site—it is hard enough to get a building done when everyone speaks the same language. Obviously the project was abandoned. Then, just to make sure these troublesome humans did not reunite, God dispersed them over the face of the earth.

While the Tower of Babel story is meant to instruct about the dangers of human arrogance in the face of God’s power, it also illustrates the ancient association of buildings and power. Indeed, in most of the world one of the most enduring activities of power—political, cultural and economic—is building. Not only building, but building well—extensively, extravagantly, durably. It takes tremendous wealth, time, cooperation and labor to secure, organize and deploy resources in such a way as to make a significant work of architecture. The Tower of Babel is the perfect example of such power. It was perhaps because of this that Hegel claimed this was the first recorded act of architecture. In this way, architecture gets bundled up with power and building from the very foundation of our imagination about human culture.

Few people in positions of significant power can resist the urge to build. Monuments, palaces, governmental centers, corporate headquarters, temples, palatial residences and even entire cities reflect the sensibilities and organization of power long after the individuals and entities that wielded them are gone. By contrast, the humble dwellings of the vast majority of the world’s inhabitants are remarkably impermanent—washing away in floods, crumbling in earthquakes, disintegrating over time or disappearing under further layers of building. In these instances, what survives may not be the actual building, but the practice of making and renewing, the patterns of habitation, the craft of ornamentation.

One other lesson endures in the story of Babel: the lesson of the potential of agency. Agency, the power to act on behalf of someone else, or on one’s own behalf, is a prerogative of certain kinds of freedom. It assumes that one has the right to pursue what can be imagined, what can be undertaken. In the case of the tower at Shinar, the people imagined a tower to heaven—something they had the power and freedom to pursue on their own behalf. God, however, quickly came to realize that He had given them too much autonomy, and just as quickly took away the agency they had assumed. He made them speak different languages; dividing them through an inability to communicate. Then He scattered them to the corners of the earth; dividing them spatially as if to emphasize in the physical realm what had already happened in the social. In this way, the agency of the people to build the tower was taken away in the most overt terms. And we are given a definitive lesson on how power operates through the control of agency.

In his book about power and the architecture of national capitals, Lawrence Vale warms up to his subject with a quote from Lewis Mumford on the role of the citadel in a city:

In the citadel the new mark of the city is obvious: a change of scale, deliberately meant to awe and overpower the beholder. Though the mass of the inhabitants might be poorly fed and overworked, no expense was spared to create temples and palaces whose sheer bulk and upward thrust would dominate the rest of the city. The heavy walls of hard-baked clay or solid stone would give to the ephemeral offices of state the assurance of stability and security, of unrelenting power and unshakable authority.

What we now call “monumental architecture” is first of all the expression of power, and power exhibits itself in the assembly of costly building materials and of all the resources of art.

What we now call “monumental architecture” is first of all the expression of power, and power exhibits itself in the assembly of costly building materials and of all the resources of art.

(Mumford 1961 cited in Vale 1992:13)

What drives this desire of the powerful to build? Some have attributed it to an arrogant need to make physical the power that is wielded. Others think it is a desire to leave a permanent marker of greatness that will communicate forward into history the power of the moment; like procreation, it is an attempt to ward off the annihilation of death by leaving a mark on the physical world. On a more basic human level, as it was for those at Shinar, it is also a way for a person to extend themselves into a larger, built scale—a way of declaring presence in the current moment. Indeed, it may be that the desire to build has little to do with power—but power gives access to the resources to build large and in ways that survive time.

For many architects, the usual discussion about space and power has to do with the organization of architectural space to facilitate vision or surveillance. Most famous is the example of the work of Jeremy Bentham, and his work on the idea of the “panopticon”: the arrangement of spaces so that they can be seen, therefore controlled, from a central point. Bentham’s theories, usually resulting in a radial plan, were most effectively applied to prison design. François Mitterrand, father of the stunning French “Grands Projets” of the 1980s and 1990s, clearly understood the importance of architecture in this context. He is quoted by Julia Trilling in Atlantic Monthly as saying, “an epoch is inscribed in its monuments [so] architecture is not neutral[;] it expresses political, social, economic and cultural ‘finalities’” (Goodman 1988:43).

Architects are deeply embedded in this power structure. We provide services to those who can pay and to those who command the resources to build the expensive cultural artifacts we design. Yet, this connection between architecture and power is a part of the much larger entanglement between power and the control of space. That is, buildings are only a portion of the way that power operates spatially, since power extends to scales both smaller and far larger. At the smaller scale, power controls human bodies through spatial strategies of segregation (that is, making certain bodies invisible or keeping them physically separated), marginalization, exile, imprisonment and banishment. But of course, these same strategies are extended out to the scale of architecture, cities, landscapes, and even nations. At the scale of a building, architecture can reinforce these strategies, with segregation added to the many roles a single building must serve.

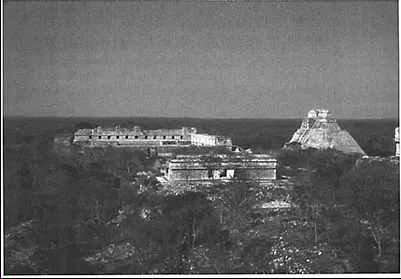

Figure 1.1 The Maya built this temple complex at Uxmal on the Yucatan Peninsula

Among the most damaging and difficult to reverse exercises of spatial power, however, are those that operate at very large scales. In particular, the processes of colonialism and globalization have enormous impacts on the way space is controlled, allocated and inhabited within their spheres of influence – they use all the spatial strategies at their disposal to do this. The power of the forces at work at this scale are so enormous that individuals have little leverage to defy them or the attitudes of superiority, cultural disdain and racism that often accompany them. A sense of inevitability and helplessness accompanies such vast reorganizations of space. Such an exercise of power robs people of the ability to act on their own behalf in political, economic, cultural and spatial terms. This denial of agency is both a brutal outcome of repressive power and the seed of effective resistance to it.

Space and Power

Taking possession of space is the first gesture of living things, of men and animals, of plants and clouds, a fundamental manifestation of equilibrium and duration. The occupation of space is the first proof of existence.

(Le Corbusier 1948)

Le Corbusier, writing in the aftermath of the vast spatial disruptions, displacements and destruction of the Second World War, gives a poetic primacy to the idea of “taking possession of” ‘ that is, owning, controlling and acting within – physical space. “Possess”, “own” and “control” all imply the power of an individual over this primal, and seemingly inalienable, space of existence. In the numb silence following the war, this small idea was a premonition of the widespread challenges to political, social and cultural power that would soon rush to encompass the world. The dismantling of colonial structures, the rise of civil rights, the expansion of the rights of women and the painful reemergence of indigenous peoples from the shadows began breaking down the monolithic power structures that had defined much of history and dictated spatial practices for centuries.

This dismantling continues today, creating ever more unstable, diverse and diffused systems of power relations. While power shifts and spreads, the physical constructs and spatial practices left behind by previous regimes remain as more permanent marks on the landscape. These spatial wounds are not neutral. They were made using strategies to embody particular attitudes, cultural practices and ideologies. They are specifically designed to support and encourage these practices. Rearranging or erasing these spaces to reflect a new set of ideas, constituents and power relations is a long-term endeavor necessary to complete any political, cultural and social transformation.

What does Le Corbusier mean exactly when he talks about the “occupation” of space? The inhabitation of space (and here we must assume he means more than simply replacing some volume of air) is intimately connected to the exercise of individual liberty. Conversely, not having control of the space one is occupying is in some way demoralizing—depriving life of one of its essential modes of existence. To remove from a person her or his right to act in space is to deny that person any kind of spatial agency. That is, it is to take away the power of individuals to determine movement through the world and to rob them of the dignity of the spatial aspect of free will. Indeed, throughout human history one of the most effective means of exercising power has been to conquer, circumscribe and control a people’s space.

In addition to actual movement through and occupation of space, possession of space might extend to how one represents oneself in space. This representation can happen at multiple scales: from the level of the body, through hair, clothing and adornment, to the level of the landscape, through buildings and gardens. While individuals can exercise some level of control over their body, the degree of control decreases with the increase in the scale of the space where one is attempting to be represented.

Architects take for granted that the term “space” means actual physical volumes of air, perhaps circumscribed by walls and a roof, or by edges of buildings, or even a chain of mountains. Henri Lefebvre’s seminal 1971 book The Production of Space significantly widened the discussion of space by directly relating social constructions and relationships to the production of physical space at a wide range of scales. This analysis was part of the shift in the use of the term “space”. A number of disciplines outside of architecture began to describe as “space” non-physical ideas or social constructions that flow from place to place almost as if they were molecules of air caught on a prevailing wind—and in this way operate as if in a unique world with its own laws of physics. The word “space” then is used to reinforce the ubiquitous nature and fluid distributions of certain concepts and conditions discussed. And the word “flow”, with its image of water or hot lava, introduces the element of time to such discussions.

Geography is a discipline explicitly interested in space of all kinds, from the kind of spatial “flows” that political economists address and the “social space” of sociologists, to the manifestations of natural systems, culture, money and power in actual physical space. For geographers the idea of flow reiterates the importance of the dimension of time when discussing space. Geographer David Harvey puts it this way:

Armed with the right kitbag of tools, it is possible to set up common descriptive frames and modeling procedures to look at all manner of flows over space, whether it be of commodities, goods, ideas, energy, ecological inputs. The diffusion of cultural forms, diseases, biota, ideas, consumption habits, fashions; the networks of communications, energy transfers, water flows, social relations, academic contacts: the nodes of centralized power, of city systems, innovation and decision-making; the surfaces of temperature, evapotranspiration potential, of population and income potential; all these elements of spatial structure become integral to our understanding of how phenomena are distributed and how processes work through and across space over time.

(Harvey 2001:223)

These flows, however, are slowed down by physical distance: the greater the distance, the slower the flow. A letter containing vital information that used to take weeks to cross the Pacific by ship can now be zapped in an instant via the Internet. Harvey goes on to join in the widely held speculation that much of the human agenda driving invention is to lessen the physical drag of space by continually reducing “the friction of distance”.

Attempts to deal with these dynamic systems of spatiality—generally under the rubric of the “social construction” or “production” of space— are now legion. The whole history of capital accumulation which, as Marx long ago observed, has embedded within it an historical tendency towards the annihilation of space through time, points to an evolutionary process in which relevant metrics and measures of both space and time have been changed significantly. Speed-up of turnover time and reductions in the friction of distance have meant that spatio-temporality must now be understood in a radically different way from what was operative in, say, classical Greece, Ming Dynasty China, or mediaeval Europe.

(Harvey 2001:224, emphasis added)

Just as technology has allowed physical objects to move faster through space, it has also allowed for information, ideas, capital, communications and other non-physical entities to move faster as well. In these ways, as Harvey says, the general term “space” applies to all kinds of networks: financial, informational, social, intellectual, cultural and so on. However, this now widespread use requires that we now must qualify the word “space”: space of flows, economic space, social space, and so on. A common example of the wider applications of the term is “cyber-space”—a conceptual location made very real by the social and cultural interactions and economic transactions that take place through digital connections. This is a growing world parallel to, and often separate from, physical spaces.

While architecture, as a profession, may not deal with non-physical space very often, some of the ideas about “space” from the various thinkers about its different modes have value for our current conversation. This is particularly true when it comes to the discussion of the relationship of power and these spaces. And, indeed, discussions of space and power ultimately return, most notably in Lefebvre, to buildings.

This analysis leads back to buildings…. In their pre-eminence, buildings, the homogeneous matrix of capitalistic space, successfully combine the object of control by power with the object of commercial exchange. The building effects a brutal condensation of social relationships… It embraces, and in doing so reduces, the whole paradigm of space: space as domination/appropriation (where it emphasizes technological domination); space as work and product (where it emphasized the product); and space as immediacy and mediation (where it emphasizes the mediations and mediators).

(Lefebvre 1991:227)

Once again, recent work in Geography is of particular interest to this discussion. In a logical extension of their field in the era of deconstruction and postcolonialism, geographers came early to the analysis of the affects of power on physical space. As David Harvey observed in 1973: “Dominant organizations and institutions make use of space hierarchically and symbolically. Sacred and profane spaces are created, focal points emphasized, and space is generally manipulated to reflect status and prestige” (Harvey 1973:280).1

Geographers have also made important contributions toward the analysis of how power is embedded in various representations of space. Harvey writes that “map-making and cartography have been central to the history of Geography…. Cartography is about locating, identifying and bounding phenomena and thereby situating events, processes and things within a coherent spatial frame. It imposes spatial order on phenomena” (Harvey 2001:219–220). Noted cartographic historian, J.B.Harley was among the first to view maps as texts that could be deconstructed with a view toward understanding the underlying motivations within them. This led him, naturally, to write extensively about the connection between cartography and power:

Cartographers manufacture power. They create a spatial panopticon. It is power embedded in the map text. We can talk about the power of the map just as we already talk about the power of the word or about the book as a force for change. In this sense maps have politics. It is a power that intersects and is embedded in knowledge. It is universal.

(Harley 2001: cover flap)

In describing a map as a tool of power, Harley provokes thoughts of looking past the power itself to the techniques power deploys to achieve its ends. There is a difference between describing the physical results of power in the landscape and addressing the time-based relationship between space and power on a strategic and tactical level. By understanding what strategies power uses to affect space, to control it, to possess it; it is then possible to contemplate counter-strategies to undo coercive spatial practices and to restore spatial agency.

The Spatial Strategies of Power

On the level of culture and society, there are four broad categories of spatial strategies of power: (1) the construction of hierarchies, (2) segregation, (3) marginalization, and (4) long-term, large-scale mechanisms of spatial transformation like apartheid, colonialism and globalization. Each of these has a particular paradigm of operation, and each impacts at various scales of physical space. From the scale of the body, up through the scale of buildings and cities to the scale of the landscape, power exercises explicit and implicit control over the shaping and occupat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Building Change

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Power, Space and Architecture

- Chapter 2: Building Future Tjibaou Cultural Centre

- Chapter 3: Building Visibility Uluru Kata-Tjuta Cultural Centre

- Chapter 4: Building Memory The Museum of Struggle

- Chapter 5: Building Presence

- Chapter 6: Architecture and Change

- Appendix Project Credits

- Notes

- Bibliography