This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

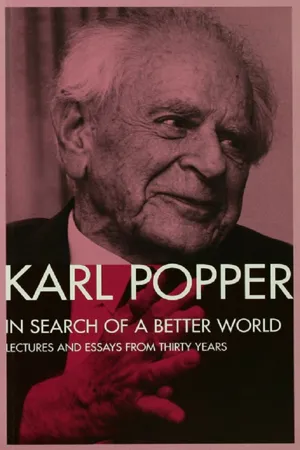

'I want to begin by declaring that I regard scientific knowledge as the most important kind of knowledge we have', writes Sir Karl Popper in the opening essay of this book, which collects his meditations on the real improvements science has wrought in society, in politics and in the arts in the course of the twentieth century. His subjects range from the beginnings of scientific speculation in classical Greece to the destructive effects of twentieth century totalitarianism, from major figures of the Enlightenment such as Kant and Voltaire to the role of science and self-criticism in the arts. The essays offer striking new insights into the mind of one of the greatest twentieth century philosophers.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access In Search of a Better World by Karl Popper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

On Knowledge

1

Knowledge and the Shaping of Reality

The Search for a Better World

The first half of the title of my lecture was not chosen by me, but by the organizers of the Alpbach Forum. Their title was: ‘Knowledge and the Shaping of Reality’.

My lecture consists of three parts: knowledge; reality; and the shaping of reality through knowledge. The second part, which deals with reality, is by far the longest, since it contains a great deal by way of preparation for the third part.

1. Knowledge

I shall start with knowledge. We live in a time in which irrational-ism has once more become fashionable. Consequently, I want to begin by declaring that I regard scientific knowledge as the best and most important kind of knowledge we have – though I am far from regarding it as the only one. The central features of scientific knowledge are as follows:

1. It begins with problems, practical as well as theoretical.

One example of a major practical problem is the struggle of medical science against avoidable suffering. This struggle has been extremely successful; yet it has led to a most serious unintended consequence: the population explosion. This means that another old problem has acquired a new urgency: the problem of birth control. One of the most important tasks of medical science is to find a genuinely satisfactory solution to this problem.

It is in this way that our greatest successes lead to new problems.

An example of a major theoretical problem in cosmology is how the theory of gravitation may be further tested and how unified field theories may be further investigated. A very great problem of both theoretical and practical importance is the continued study of the immune system. Generally speaking, a theoretical problem consists in the task of providing an intelligible explanation of an unexplained natural event and the testing of the explanatory theory by way of its predictions.

2. Knowledge consists in the search for truth – the search for objectively true, explanatory theories.

3. It is not the search for certainty. To err is human. All human knowledge is fallible and therefore uncertain. It follows that we must distinguish sharply between truth and certainty. That to err is human means not only that we must constantly struggle against error, but also that, even when we have taken the greatest care, we cannot be completely certain that we have not made a mistake.

In science, a mistake we make – an error – consists essentially in our regarding as true a theory that is not true. (Much more rarely, it consists in our taking a theory to be false, although it is true.) To combat the mistake, the error, means therefore to search for objective truth and to do everything possible to discover and eliminate falsehoods. This is the task of scientific activity. Hence we can say: our aim as scientists is objective truth; more truth, more interesting truth, more intelligible truth. We cannot reasonably aim at certainty. Once we realize that human knowledge is fallible, we realize also that we can never be completely certain that we have not made a mistake. This might also be put as follows:

There are uncertain truths – even true statements that we take to be false – but there are no uncertain certainties.

Since we can never know anything for sure, it is simply not worth searching for certainty; but it is well worth searching for truth; and we do this chiefly by searching for mistakes, so that we can correct them.

Science, scientific knowledge, is therefore always hypothetical: it is conjectural knowledge. And the method of science is the critical method: the method of the search for and the elimination of errors in the service of truth.

Of course someone will ask me ‘the old and famous question’, as Kant calls it: ‘What is truth?’ In his major work (884 pages), Kant refuses to give any further answer to this question other than that truth is ‘the correspondence of knowledge with its object’ (Critique of Pure Reason, 2nd edition, pp. 82 f.1). I would say something very similar: A theory or a statement is true, if what it says corresponds to reality. And I would like to add to this three further remarks.

1. Every unambiguously formulated statement is either true or false; and if it is false, then its negation is true.

2. There are therefore just as many true statements as there are false ones.

3. Every such unambiguous statement (even if we do not know for certain if it is true) either is true or has a true negation. It also follows from this that it is wrong to equate the truth with definite or certain truth. Truth and certainty must be sharply distinguished.

If you are called as a witness in court, you are required to tell the truth. And it is, justifiably, assumed that you understand this requirement: your statement should correspond with the facts; it should not be influenced by your subjective convictions (or by those of other people). If your statement does not agree with the facts, you have either lied or made a mistake. But only a philosopher – a so-called relativist – will agree with you if you say: ‘No, my statement is true, for I just mean by truth something other than correspondence with the facts. I mean, following the suggestion of the great American philosopher William James, utility; or, following the suggestion of many German and American social philosophers, what I mean by truth is what is accepted; or what is put forward by society; or by the majority; or by my interest group; or perhaps by television.’

The philosophical relativism that hides behind the ‘old and famous question’ ‘What is truth?’ may open the way to evil things, such as a propaganda of lies inciting men to hatred. This is probably not seen by the majority of those who represent the relativist position. But they should have and could have seen it. Bertrand Russell saw it, and so did Julien Benda, author of La Trahison des Clercs (‘The Treason of the Intellectuals’).

Relativism is one of the many crimes committed by intellectuals. It is a betrayal of reason and of humanity. I suppose that the alleged relativity of truth defended by some philosophers results from mixing-up the notions of truth and certainty; for in the case of certainty we may indeed speak of degrees of certainty; that is, of more or less reliability. Certainty is relative also in the sense that it always depends upon what is at stake. So I think that what happens here is a confusion of truth and certainty, and in some cases can be shown quite clearly.

All this is of great importance for jurisprudence and legal practice. The phrase ‘when in doubt, find in favour of the accused’ and the idea of trial by jury show this. The task of the jurors is to judge whether or not the case with which they are faced is still doubtful. Anyone who has ever been a juror will understand that truth is something objective, whilst certainty is a matter of subjective judgement. This is the difficult situation that faces the juror.

When the jurors reach an agreement – a ‘convention’ – this is called the ‘verdict’.2 The verdict is far from arbitrary. It is the duty of every juror to try to discover the objective truth to the best of his knowledge, and according to his conscience. But at the same time, he should be aware of his fallibility, of his uncertainty. And where there is reasonable doubt as to the truth, he should find in favour of the accused.

The task is arduous and responsible; and it demonstrates clearly that the transition from the search for truth to the linguistically formulated verdict is a matter of a decision, of a judgement. This is also the case in science.

Everything I have said up to now will doubtless lead to my being associated with ‘positivism’ or with ‘scientism’ once again. This does not matter to me, even if these expressions are being used as terms of abuse. But it does matter to me that those who use them either do not know what they are talking about or twist the facts.

Despite my admiration for scientific knowledge, I am not an adherent of scientism. For scientism dogmatically asserts the authority of scientific knowledge; whereas I do not believe in any authority and have always resisted dogmatism; and I continue to resist it, especially in science. I am opposed to the thesis that the scientist must believe in his theory. As far as I am concerned ‘I do not believe in belief, as E. M. Forster says; and I especially do not believe in belief in science. I believe at most that belief has a place in ethics, and even here only in a few instances. I believe, for example, that objective truth is a value – that is, an ethical value, perhaps the greatest value there is – and that cruelty is the greatest evil.

Nor am I a positivist just because I hold it to be morally wrong not to believe in reality and in the infinite importance of human and animal suffering and in the reality and importance of human hope and human goodness.

Another accusation that is frequently levelled against me must be answered in a different way. This is the accusation that I am a sceptic and that I am therefore either contradicting myself or talking nonsense (according to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus 6.51).

It is indeed correct to describe me as a sceptic (in the classical sense) in so far as I deny the possibility of a general criterion of (non-tautological) truth. But this holds of every rational thinker, say, Kant or Wittgenstein or Tarski. And, like them, I accept classical logic (which I interpret as the organon of criticism; that is, not as the organon of proof, but as the organon of refutation, of elenchos). But my position differs fundamentally from what is usually termed sceptical these days. As a philosopher I am not interested in doubt and uncertainty, because these are subjective states and because long ago I gave up as superfluous the search for subjective certainty. The problem that interests me is that of the objectively critical rational grounds for preferring one theory to another, in the search for truth. I am fairly sure that no modern sceptic has said anything like this before me.

This concludes for the moment my remarks on the subject of ‘knowledge’; I now turn to the subject of ‘reality’, so that I may conclude with a discussion of ‘the shaping of reality through knowledge’.

2. Reality

I

Parts of the reality in which we live are material. We live upon the surface of the earth which mankind has conquered only recently – during the eighty years of my life. We know a little about its interior, with the emphasis upon ‘little’. Apart from the earth, there are the sun, the moon and the stars. The sun, the moon and the stars are material bodies. The earth, together with the sun, the moon and the stars, furnishes us with our first idea of a universe, of a cosmos. The investigation of this universe is the task of cosmology. All sciences serve cosmology.

We have discovered two kinds of bodies on earth: animate and inanimate. Both belong to the material world, to the world of physical things. I will call this world ‘world 1’.

I shall use the term ‘world 2’ to refer to the world of our experiences, especially the experiences of human beings. Even this terminological and provisional distinction between worlds 1 and 2, that is, between the physical world and the world of experiences, has aroused much opposition. All I mean by this distinction, however, is that world 1 and world 2 are at least prima facie different. The connections between them, including their possible identity, are among the things that we need to investigate using hypotheses, of course. Nothing is prejudged by making a verbal distinction between them. The main point of the suggested terminology is to facilitate a clear formulation of the problems.

Presumably animals also have experiences. This is sometimes doubted; but I do not have the time to discuss such doubts. It is perfectly possible that all living creatures, even amoebae, have experiences. For as we know from our dreams or from patients with a high fever or similar conditions, there are subjective experiences of very different degrees of consciousness. In states of deep unconsciousness or even of dreamless sleep we lose consciousness altogether, and with it our experiences. But we may suppose that there exist also unconscious states, and these too can be included in world 2. There may perhaps also be transitions between world 2 and world 1: we should not rule out such possibilities dogmatically.

So we have world 1, the physical world, which we divide into animate and inanimate bodies, and which also contains in particular states and events such as stresses, movements, forces and fields of force. And we have world 2, the world of all conscious experiences, and, we may suppose, also of unconscious experiences.

By ‘world 3’ I mean the world of the objective products of the human mind; that is, the world of the products of the human part of world 2. World 3, the world of the products of the human mind, contains such things as books, symphonies, works of sculpture, shoes, aeroplanes, computers; and also quite simple physical objects, which quite obviously also belong to world 1, such as saucepans and truncheons. It is important for the understanding of this terminology that all planned or deliberate products of man’s mental activity are classified within world 3, even though most of them may also be world 1 objects.

In this terminology, therefore, our reality consists of three worlds, which are int...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- A summary by way of a preface

- Translator’s acknowledgements

- Part I: On knowledge

- Part II: On history

- Part III: Von den Neuesten … zusammengestohlen aus Verschiedenem, Diesem und Jenen*

- Appendix

- Name index

- Subject index