eBook - ePub

Courtyard Housing

Past, Present and Future

This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Courtyard housing is one of the oldest forms of domestic development spanning at least 2000 years and occurring in distinctive form in many regions of the world. Traditionally associated with the Middle East where climate and culture have given shape to a particular type of courtyard housing, other examples exist in Latin America, China and in Europe, where the model has been reinterpreted. This book demonstrates, through discussions on sustainability and regional identity, and via a series of case studies, technical planning and design solutions, that the courtyard housing form has a future as well as a past.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Courtyard Housing by Brian Edwards, Magda Sibley, Mohammad Hakmi, Peter Land in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Arquitectura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1 History and theory

1 The courtyard house: typological variations over space and time

ATILLIO PETRUCCIOLI

Introduction

Studies of the courtyard house rest on an ever-present ambiguity that tends to perpetuate the image of a generic and universal type, indifferent to the site and immutable over time. However, the work of Orientalists and Arabists, celebrating the courtyard as the heart of the dar, the extended family, have confused matters in architectural terms. Satisfied with generic symbolic and functional virtues, they have omitted structural and typological components that are essential to the full appreciation of the courtyard house. They have failed to recognize the historical phases which mark the change of the type and its various translations in different geographical locations.

In the following passage Vittorio Gregotti underscores the tectonic importance of the courtyard as an architectural act par excellence:

The enclosure not only establishes a specific relationship with a specific place but is the principle by which a human group states its very relationship with nature and the cosmos. In addition, the enclosure is the form of the thing; how it presents itself to the outside world; how it reveals itself.1

Given the fact that the archetype courtyard house represents a primordial act of enclosure and construction, it is senseless to establish a primogeniture for something that is as essential to mankind as the wheel. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consider that every cultural region developed shelter and enclosure along different lines, through the choice of a specific elementary cell or by addressing the typological process in a specific direction.

This chapter seeks to describe the typological processes inherent in the evolution of the Mediterranean ‘Islamic’ courtyard house with reference to the forces intrinsic to the building plot. It will also discuss the complex problems found at the level of the aggregation of building types and the accumulation of the courtyard house into the characteristic Middle Eastern city.

The courtyard house

In the typological history of the courtyard house there was a critical moment when a precursor marked off an area around a monocellular unit by an enclosing wall. After that the enclosing wall became a reference point, with an aggregation of more cells around a central space. Unlike the side by side placement of serial cells, the enclosure simultaneously suggests the final form of the courtyard house and emphasizes its inward looking content.

Much has been written about the sacred significance of the courtyard house. For example, it has been suggested that the courtyard of an Arab house evokes the Garden of Eden.2 Gottfried Semper3 associated the enclosure with a southern Mediterranean agricultural society that must struggle to coax a harvest from grudging soil and protect it from the elements; G.Buti used linguistics to tie it to Indo-European nomadic people. The type is, however, a generic domestic form of residence which independently evolved in various places from the Egyptian-Sumerian civilization to the Mediterranean, Asia Minor, and right up to the Indus Valley.4 The closed and reinforced courtyard house is thus a product of cultural polygenesis dating from the Bronze Age, and it has endured in the Mediterranean basin in the form of the classical Roman atrium and Greek pastas house.

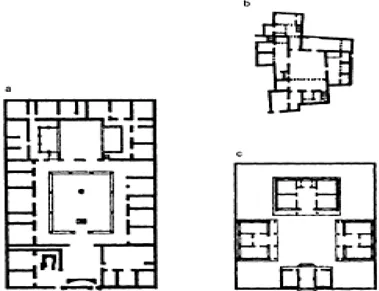

The kernel of the type is the concept of the organism or better, the specific balance between a serial and/or organic attitude of putting together forms that is the genetic patrimony of every culture. A courtyard house in Jilin, China, a courtyard house in Fez and a domus in Italica, Spain, are, however, deeply different in spite of a generic similarity. The Chinese house disposes its pavilions inside the enclosure in a scattered manner, scarcely related to the wall of the perimeter. The house in Fez lays out the elementary cells enmeshed along the border of the plot, while double symmetry controls the regularity of the patio, but without influencing the whole building. The domus in Italica disposes the cells around the peristyle in an organic way, ordered by a biaxial symmetry that crosses the whole building from the entrance to the exedra. Spaces have different sizes and are hierarchically composed in a variety of ways, in spite of their superficial similarity as courtyard houses.

1.1 Three examples of courtyard houses which appear identical but feature different uses of seriality: (a) house in Italica, Spain, (b) house in Fez, Morocco, (c) house in Jilin, China

In order to better understand the courtyard model in all of its guises it is useful to introduce the fundamental typological differences between the courtyard house and the row (or terraced) house. The row house always lies on a road, faces onto it, and is directly accessible to it from the outside. Its pertinent area is behind, to be covered in subsequent stages as the area is filled in. The pre-eminence of the building site and the high property value attached to its facing front determine the dimensions of the lot, the front of which is equivalent to the size of the elementary cell, usually around 5 metres. The courtyard on the contrary has a superior sense of the familial territory, so that the form coincides with borders of the same territory. The same strict relationship to the road does not apply in the courtyard type, so any side of the lot can face the street without interfering with the internal organization of the house. A first building is even conceivable in which the courtyard is some distance from the road. The unbuilt area dominates the built area because the former must mediate between the inside and the outside of the enclosure as well as distribute the organism from within. Furthermore, the courtyard-house type lacks external openings: they appeared only recently in both East and West following a lengthy process and exclusively in urban areas. The fact that a room has only one source of light, that is, from the courtyard, limits its depth to 6 metres or less, depending on the size of the elementary cell used by a society. This depth can be extended by adding a groundfloor portico into the courtyard with a loggia on the upper level. The building bay can be doubled only by making an opening in the wall that faces the street, which then allows the portico to be enclosed.

Guy Petherbridge offers an overall explanation for the dispersal of the courtyard house type by distinguishing two varieties:

The interior courtyard house, where the house encloses a courtyard, characteristic of urban areas; and the exterior courtyard house, where the courtyard borders the house, providing a protected area contiguous with the dwelling units but not enclosed by them.5

Andre Bazzana finds that this distinction holds for the Iberian peninsula; he calls the first ‘block-like’ and the second ‘attached’. According to Bazzana the difference between the two is a result of a difference in economies: the exterior court yard was used by seminomads; the interior courtyard, patterned after the ksar of the Sahara, was originally inhabited by sedentary farmers.6 Such a schematic analysis is doubtful since it is conducted at too low a level of typological specificity. Petherbridge’s contrast between the two models assumes a stereotyped dichotomy between urban mercantile and rural society which does not allow for a plethora of intermediate positions. The contrast is artificial, and is less the result of an Orientalist mentality than the mindset of geographers, who focus on territory, and historians, such as Torres Balbas, who concentrate on exceptions, such as the opulent and lavishly decorated homes of merchants and city officials.

Furthermore, if we look closely at local typological processes in the Maghreb and Andalusia, we not only discover the inappropriateness of the closed and open models of the courtyard house as an explanation, but also discover that the Arab–Islamic city, whose fabric gives the impression of being frozen in time between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries, is not monotypological at all. On the contrary, it is based on a wealth of variants which in no way jeopardize the fundamentals of the courtyard type. Misconceptions like Bazzana’s result from the fact that the idea of an elementary courtyard lingers in the cultural memory long after its physical demise, and is replicated and reused in the same area even after a substantial lapse of time.

General nomenclature and typological process

The approach here is to begin the analysis of typological processes with the study of the rural version of the courtyard house. The limited changes it undergoes allows for a clearer reading of the matrix type and early diachronic phases. Generally there are two types of rural buildings in the same enclosure: the residence and the annexes, which include stables and a shed for tools and farming equipment. Annexes are usually located on the side opposite the house. When the residential part of a structure in an enclosure is located on the side in front of the entrance, they either line up parallel to the entrance or on the perpendicular side. In North African Arab–Islamic urban houses, traces of these annexes coincide with the kitchen or metbah, the pantry area or bayt el-hazim, and the bathroom, and are grouped together on the side opposite the main bayt.7 The dimensions of the enclosure are in no way restricted by the built area: such interdependence is a feature mainly of urban planning. In the Mediterranean, one finds it in both the ancient Greek pastas house, whose frontage varies between 9 and 18 metres8 and the Roman domus, whose frontage measures between 12 and 18 meters.9

Two key factors in the first phase determine the whole growth of the house: orientation and access. The building unit is oriented to take the greatest advantage of direct sun, which in the Mediterranean basin corresponds to a south southwestern exposure. Because choice of orientation relates more to production needs than to the building itself, this rule is rigid in rural areas but not so strictly adhered to in towns, although it is still prevalent in the majority of the town houses. Given the prevalence of a southern orientation, the built part within the enclosure is either parallel or perpendicular to the road. There are then only three possible access variants for the courtyard house: in the first case, when the building is parallel and adjacent to the route, entry is through the building unit, where in order not to limit the distributive possibilities of the building, it is pushed to a far end. In the other two cases, the building is either opposite or perpendicular to the road, and the entry lies in the centre of the free side.

Figures 1.2–1.6 demonstrate situations that produce different diachronic variations, their relative processes, and the most interesting transitions in these processes. These transitions, in turn, are capable of generating parallel processes of synchronic variants which for reasons of space are not represented in the various diagrams.

In the A1–2–3 (Figure 1.2) series the elementary courtyard is gradually transformed as more and more of its area is covered, so that activities that once took place outdoors begin to take place indoors. This is achieved through the addition of rooms on the opposite side of the initial cell; these new rooms are then consolidated with a portico, after which the two parts are unified by a covered passage, and the process ends by forming a courtyard in the centre. Because the example in this series is single family, mezzanines and other possible vertical additions typical of different processes are not included, although it is common to reserve at least one cell with an independent external entry for newly-wed couples or house guests.10

In this first series, the house has a rather low level of specialization. The plot size, even in an urban area, is large enough to allow division of function on a single level. Further hier...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Courtyard Housing

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Illustration credits

- Contributors

- Foreword—Courtyard: a typology that symbolises a culture

- Preface

- Part 1 History and theory

- Part 2 Social and cultural dimensions

- Part 3 Environmental dimensions

- Part 4 The contemporary dimension

- Bibliography

- Glossary