This is a test

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Dance Masters is a lively ensemble of conversations with seven celebrated dancers and choreographers. In these intimate interviews, dance critic Janet Lynn Roseman probes the heart of dance:

* The creative process

* The role of dream and rituals

* The interplay between dancer and audience

* The spiritual aspects of performance These dance masters offer rare insights into the internal world of the artist as they reveal their philosophies on dance training, discuss their mentors, and speak candidly about the artistic process of dance-making and how it actually feels to dance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Dance Masters by Janet Lynn Roseman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Edward Villella

"The moment Villella bursts into view a kind of magnetic rapport snaps on between himself and the audience. As he flashes across the stage he creates the illusion that the music isn't fast enough, the ceiling isn't high enough, the stage isn't big enough to contain the dancing demon that somehow has invaded this small, five foot seven and a half mortal. Take, for example, Tarantella, a nine-minute ballet that Balanchine choreographed to showcase Villella's special virtuosity. With a snaggle-toothed grin stamped on his face, with a mischievous twinkle for his delectable partner, Patricia McBride, Villella soars birdlike in the air and hangs at the apogee a beat longer than gravity permits. Leaping, spinning, dashing, bouncing, he threatens to explode with vitality, ecstasy, life."

—David Martin, 1969

Edward Villella has performed in some of the finest ballets ever made, courtesy of the genius of choreographer George Balanchine, including leading roles in Apollo, Agon, Prodigal Son, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Tarantella, Bugaku, and Jewels. His rise in the world of dance is a mythic tale. He began studying ballet as a child when his mother forced him to take ballet class at the School of American Ballet with his sister. Mrs. Villella wanted to keep him off the streets of the neighborhood in Queens, New York, after the young boy was knocked unconscious playing sports with his friends. Ironically, the young athlete resisted taking classes and was more than a bit embarrassed to study, but he soon fell in love with ballet and discovered that he had a great talent for it. Jerome Robbins's Afternoon of the Faun was inspired by Villella's dancing when the choreographer watched the teenage dancer at the School of American Ballet's studios.

When he was at Rhodes Prep he crossed paths with fellow dancer Allegra Kent. After a few years of dance study at SAB, which fed the burning conviction that he would become a classical dancer, Villella was heartbroken when his parents forced him to quit dance to attend college. He attended the New York Maritime College, where he felt like he was in "prison," desperately harboring his dream to become a classical dancer. Although he excelled in his studies and athletic endeavors, Villella missed dancing. An integral part of the program at the college involved travel, and when he visited other countries he quickly searched for the best dance studios in the area to take classes. During his senior year, he secretively attended dance classes in New York, firmly committed to creating a life of dance for himself once he graduated college. That experience was not only necessary for him to retrain his body but was necessary in all respects: body, mind, and spirit.

After graduation in 1955, he returned to the New York City Ballet, where he had danced as a youngster and trained ferociously in an effort to regain the precious years of technical training that he had missed while in school. Working his body mercilessly and without pause, Villella called upon master teacher Stanley Williams to guide him. For any other serious dancer, those lost years would

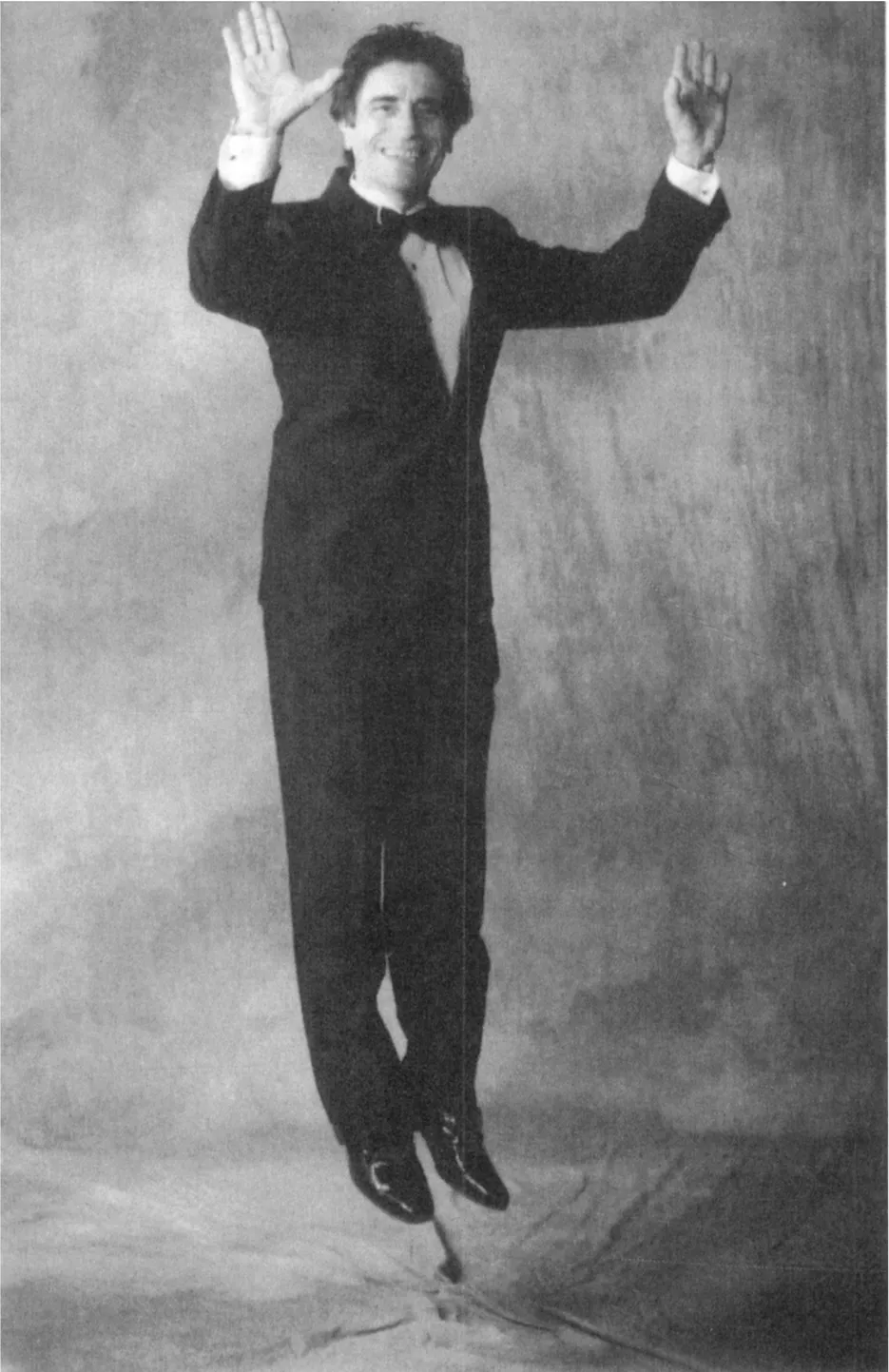

Edward Villella in studio session. Copyright Philip Bermingham.

have made it virtually impossible to dance professionally. However, Villella wasn't like other dancers. He was always observing, connecting, listening, pushing, and encouraging his body to perform beyond its natural capacity. Even when he was plagued with physical pain, he was able to do the seemingly impossible on stagesoaring in the air, leaping and spinning with so much velocity that the stage could barely contain his physical energies.

During his career with the New York City Ballet, he popularized the art form and breathed new vitality and virility into the dance. In an artistic world where more often the object d'affection was the ballerina, Villella was a notable exception, and he was quite responsible for the elevation of the male dancer in the world of ballet. When he danced, he not only conveyed the dance, he revealed it with powerful craftsmanship and great intelligence.

Mr. Balanchine created many roles for him in many ballets, including Tarantella, the Rubies section of Jewels, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and, perhaps his most famous role, The Prodigal Son. Considered one of the leading dancers in the world, and, perhaps, the best male dancer of his time, Villella was an electrifying artist and a superb athlete who was able to command both body and stage, always striving for perfect line, elevation, control, rhythm, design, and expression. Decades after he left the stage, it is still not unusual to hear his fans recall what a stunning dancer he was.

It seemed as if Villella could take on any challenge, and it wasn't unusual for him to dance not only his own rigorous repertoire, but often perform the roles of other dancers in the company, sometimes dancing two or three roles a performance. He danced with other companies as guest artist, lectured on the art of ballet, choreographed works for television appearances on "The Bell Telephone Hour" and "The Kraft Music Hall," and created three of his own ballets: Narkissos, Shenandoah, and Shostakovich Ballet Suite. In a riveting documentary called Edward Villella: Man Who Dances, audiences had the unique opportunity to view the world of dance through his eyes and experiences.

In 1975, he was severely injured while performing at the Ford White House and was unable to dance. He spent the next decade lecturing on dance and working as artistic director for several ballet companies. Currently, he is the artistic and founding director for the Miami City Ballet, and has succeeded in putting this once-fledgling ballet company on the international map. Under his deft tutelage, the company has not only reigned in Florida, but their national and international reputation has earned them a significant place in the dance world. Fiercely committed to the Balanchine repertoire, Villella continues to train dancers not only in technical virtuosity but offers them a sterling education in the Balanchine aesthetic. The former resident choreographer Jimmy Gamonet de los Heros worked closely with Villella for many years and has provided the company with elegant works that aptly complement the Balanchine programs.

When he was fifty years old, many years after departing his professional career, he returned to the stage to star in Jerome Robbins's enigmatic ballet, Watermill. It was a willful endeavor given that Villella's injuries from a lifetime of dance had almost crippled him. Robbins cajoled Villella into starring in the piece, and before Villella had agreed to dance, Robbins cleverly announced to the press that Villella had agreed, making it virtually impossible for him to extricate himself. His performance was a physical resurrection, considering that he was dancing with a body that was host to countless foot fractures and broken bones.

He has danced for presidents, was the first male dancer invited to dance with the Royal Danish Ballet, and earned an unprecedented twenty-two encores when dancing at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. He was the producer/director for the PBS specials "Dance in America" for one-and-a-half years, and won an Emmy Award in 1975 for his television production of the ballet Harlequin. In 1992 he published his autobiography (with writer Larry Kaplan), Prodigal Son: Dancing for Balanchine in a World of Pain and Magic. The book was so successful that it was reissued in 1998.

Villella has always made dance education a priority. He is eager to share his knowledge of dancemaking and performance, and continues to be one of ballet's most articulate spokesmen. For his accomplishments as an artist he has received a 1997 National Medal of the Arts, the 1997 Kennedy Center Honors, the thirty-eighth annual Capezio Award, the National Society of Arts and Letters Award for Lifetime Achievement (and was only the fourth dance personality to receive the gold medal), the Frances Holleman Breathitt Award for Excellence, and the 1964 Dance Magazine Award. He was inducted into the State of Florida Artists Hall of Fame, and holds honorary degrees from Fordham University, Skidmore College, Union College, Nazareth College, and St. Thomas University.

Now in his sixth decade, Mr. Villella wears beauty deeply etched in the crevices of his face. He has an extraordinary gift for both verbal as well as physical communication, and builds his responses in conversation as carefully as he coaches his dancers in the ballet, paying full attention to form, content, and delivery. He spoke to me with authority, remarkable precision, and imagination, demonstrating in action the creative response. His knowledge about dance reflects a man who has mastered all means of expression, a man with full play of his talents. Edward Villella aims for and reaches a supreme quality in art, a term I use in all its force.

I was reading about your mother, Edward, and her influence in your life. She impressed me quite a bit. Can you tell me more about her?

She really was a person who was way ahead of her time, and she was terrifically frustrated, which I think added to her drive and her ambition for her children. She was an orphan and didn't have opportunity. But I was also part of that drive and that ambition to get beyond what her initial circumstances were. She discovered and developed her knowledge about nutrition and about health, and I think she was interested in things that were not necessarily the mainstream. I don't think she was fully comfortable with the mainstream.

I think she was a person who had great curiosity and wanted to have a great deal of knowledge. She discovered Adele Davis long before her nutritional work was known. We were brought up on blackstrap molasses and wheat germ.

Did you ever speak to your mother about your early days in training as a dancer? It seemed as if she easily recognized that medium as a vehicle for your life early on.

We have to look at this in historical context. In the 1940s, growing up in Queens, in an Italian-American family, children didn't have too much to say. The parents were the law. Those early years were not my choice. It was only later on that I was able to exercise my own choice, and those choices became controversial. By the time I had reached some ability, I was made to stop dancing. That was the last thing I wanted to do. There were complications and difficulties, and they were resolved simply by my wanting desperately to dance and to do as much as my parents wanted from me, which was to get a college education. I tried to do both and, needless to say, it was complicated, but somehow I survived it.

You really pushed yourself, and when you were dancing, you not only danced your own roles, but everyone else's. That toll on your body was harsh. I was watching the documentary Man Who Dances, and there is a poignant moment when you are in the dressing room and you are rubbing your legs and you said, "Speak to me legs, speak to me."

Well, we speak a physical language. We have our own alphabet and our own vocabulary, and we make it into poetic gesture. When you work as much as we were required to work—performing eight times a week, dancing three to four ballets a night (and I had all of the jumping roles)—you create at least inflammation, and inflammation slows you down. That slowing down can create cramps, and cramps can stop you, and in stopping you, your body stops speaking. That flexibility is the ability to speak, and when you've lost it, it's a desperate situation if you really want to dance. One will go to all kinds of measures to make that happen.

Do you think you had an inherent trust that your body would continue?

There were a number of things that were going on. First of all, I was terrifically frustrated, and I was willful, and I willed it to happen. I wouldn't recommend that to anyone. If I had logic and sense, I wouldn't have done it that way. I lost four valuable years in my development as a dancer from age sixteen to twenty, a critical time for a dancer. I was desperate to make up that time without knowledge. I really didn't know what I was doing. It was just will, force, and tension. I abused my body, and at another juncture I had to re-address, to return to a more normal state of physicality. I had a great deal of trouble with my musculature and cramps and ailments because I was unwilling to stop, and that just compounded those injuries.

Stanley Williams was instrumental in that reeducation and the healing of your body. How wonderful that you found him, since he really preserved your ability to dance for many years and continue your career.

My great fortune was that Stanley came along and redirected my approach to training. That took years, but it really saved my dancing life. It saved a lot of my physicality. I needed a fuller in-depth investigation of my physical potential, but I also needed to investigate my physical calamities. I had these two processes that were going on at the same time: to develop my technique and progress as a dancer. But I also needed to bring back my muscles to a normal state to reduce the inflammations and to get rid of the cramping.

When you speak of being "willful" in your dancing, what do you mean by that?

I was very physical and loved to move, and that was the way I spoke and also who I was. I identified very closely with "the dancer." I was much more "the dancer" than "the person." I couldn't differentiate between dance and the dancer and the person; it was all the same to me. I think it is always there; it's not that you go step-by-step in a process. Maybe it creates a process, but the passion, the will, the frustration, the neurotic kind of energy that is involved in all of this was available all the time. I had a single purpose. It was to be a dancer and to regain who I used to be. It was very easy for me to be buried in that identity. It was exciting and I loved every minute of it. It wasn't a negative thing at all. I wished I had stepped back every now and again and just taken a deep breath, but that was not part and parcel of who I was.

Edward, we have spoken before about a dancer's intelligence, a visceral intelligence. Can you speak more about that?

There are all kinds of intelligence, and our intelligence is movement and how you understand that movement. That's the kind of intelligence I am referring to: how you move, and also how you direct that movement. You direct the taste and the temperament and the sensuality and the dramatic aspect of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Edward Villella

- 2. Merce Cunningham

- 3. Mark Morris

- 4. Catherine Turocy

- 5. Alonzo King

- 6. Danny Grossman

- 7. Michael Smuin