eBook - ePub

Measuring Quality in Planning

Managing the Performance Process

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book deals with one of the current major debates in planning: how to measure the quality and effectiveness of the output of the planning process. It deals with issues of defining quality, public sector management, the use of indicators and the planning process. Although case study material is drawn from UK practice this topic is universal and the authors include discussions of international practice and experience.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One: Planning for quality

1: Introduction—the research

This introductory chapter examines the origins of the research on which this book is based. In so doing it raises three fundamental questions that in turn represent recurring themes throughout the book. The discussion then turns to the research methodology and structure of the book which are both briefly outlined. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the use and utility of the book.

A fundamental concern

The origins of this book lie in a concern expressed repeatedly by town planners, urban designers and local councillors, and sometimes by developers and their professional advisers, during the course of a succession of research projects undertaken over a period of ten years (Punter et al., 1996; Punter and Carmona, 1997; Carmona, 2001; Carmona et al., 2001, 2002, 2003). The concern is typically expressed in three ways:

- First, that there is not enough time in the planning process to consider, influence and deliver better quality development.

- Second, that a national obsession (in England) with speed of delivery distorts local practice and priorities and undermines a concern for quality.

- Third, that in a context where performance measurement in the public sector is becoming ever more important, how will services and aspects of services that do not lend themselves to measurement fare?

The three are of course interrelated, and relate to the role and ability of planners to deliver a better quality service and influence the delivery of better quality development. Therefore, if local priorities and pressures and performance measurement systems all focus on factors such as the delivery of a faster planning service, then the time required to consider quality (whatever that means, and indeed if more time is required), or the will to influence quality, may be shut out of the process. This immediately raises three questions:

- Is more time likely to be required to deliver better quality development, or indeed better quality planning per se?

- Is a national concern for the speed of delivery distortionary?

- How can the quality of planning be measured?

Time vs. quality

To take each question in turn, the answer to the first question is inevitably and invariably ‘Yes’, because, simplistically, the delivery of better quality development (as one particularly crucial objective of a quality planning service) involves processes that take time, for example, negotiation processes, consultation processes or design processes. Take design, for example. To understand why time is such a crucial factor, it is important to first understand the nature of design as a process. In this regard design is used in the broadest sense to suggest a value—adding activity that is integral to good planning, just as it is integral to good architecture, urban design, engineering or landscape design.

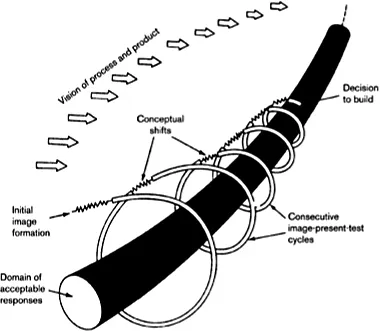

In brief, the activity of creating and managing the built environment is a creative problem-solving activity in which objectives and constraints are weighed up and balanced, and solutions which best meet a set of defined needs are derived. All design activity—product design, interior design, architectural design, systems design, graphic design, urban design and spatial planning—follows essentially the same process, a process which John Zeisel (1984) has characterised as a design development spiral (1.1).

In this conception, design (and by implication planning) is seen as a cyclical, iterative and ‘universal’ process in which solutions are gradually refined through a series of creative leaps. Hence, a problem is identified and an image of a likely solution is generated. This solution is then presented or articulated in a form which can be readily understood (i.e. through a plan); subsequently it is tested against the original problem or set of objectives, before being rejected or re-imaged to further refine the solution. This cyclical process of imaging, presenting, testing and re-imaging relies on the adequate flow of information as a means both to inspire the creative process and to test ideas. In the case of planning, this might include information about the site and context, planning policy, councillor predilections, developer and designer objectives, community aspirations and so on. The process refines the proposal continuously and moves towards a final acceptable solution.

1.1 The design development spiral

Source: Zeisel, 1984, p. 14

The nature of the design process as it interfaces with planning is therefore one that requires:

- A dialogue between stakeholders;

- An understanding of context;

- A trial and refinement process;

- An acceptance that in order to deliver the optimum solution (or as close as it is possible to get given time, resource and other constraints), sub-optimum solutions will sometimes be rejected.

Inevitably this takes time to run its course, and if the process is artificially curtailed, the outcome may be a reduction in the quality of the resulting development, and perhaps also in the quality of the service offered to the applicant (and to other stakeholders) to get there. Equally, it is likely to be the case that more time will increase quality only up to a point, and that thereafter gains will be marginal. This is either because the fundamental decisions have already been made, and the project has reached the necessary threshold standard, or because the delivery processes are failing to provide the necessary uplift in quality.

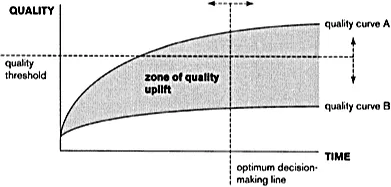

At this optimum decision-making line, a decision will need to made about whether to proceed with the proposed solution (i.e. in the case of planning, to grant planning permission, sign off a planning obligation, or adopt a particular policy or piece of guidance), or whether to abandon it (i.e. to reject it). At points in between, decisions will need to be made about whether it is worthwhile investing more time to improve the eventual outcomes, based on whether or not uplifts in quality are being achieved. The aim must be to recognise an optimum decision—making line, at which point time and quality are optimised and a decision can be made (1.2).

Note: the quality curves represent different potential time/quality trajectories for the same project. The first delivers a high-quality planning proposal and the second a poor-quality proposal. At the optimum decision-making line, both curves are delivering only small uplifts in quality and so further time spent on their planning and design may not be worthwhile. In curve A the proposal has already surpassed the quality threshold laid down by the authority and so planning permission is likely to be forthcoming. In curve B the proposal is deficient and should be rejected. The optimum decision-making line is likely to move in time depending on the nature of the development, and will be independent of the quality threshold defined during the planning process, which may also vary depending on the context.

1.2 Time/quality curves

Speed and distortion

Turning to the second question—Is a national concern for the speed of delivery distortionary?—the answer is likely to be ‘lt depends’. Invariably a concern for speed to the exclusion of other issues will bring pressure to bear on those parts of the planning process that seem on the face of it to take longer (i.e. negotiation or public participation), and will therefore have the potential to distort the process to the detriment of such factors.

In other UK public services, the distortionary effect caused by the over-simplistic pursuit of certain objectives to the exclusion of others has been well documented, and includes:

- The pressure to reduce narrowly defined waiting times for certain forms of treatment in the National Health Service, which has spawned, for example, the new phenomenon of waiting lists to get on to the waiting lists.

- League tables for schools, which have led many schools to shift their emphasis from a broad holistic education to the narrow pursuit of raising examination pass rates, and from recruiting mixed-ability pupils to selectively recruiting those most likely to pass their exams.

- The pressure in the university sector to measure academic achievement and status against narrowly defined output criteria, which have led academics to seek to maximise their scores by disengaging from teaching and professional activities in favour of publication in highly specialised and narrowly read journals.

For English planning, evidence nationally has identified a significant gap in resourcing for planning services which has been impacting across planning services, and particularly on plan-making (see Chapter 5). The research suggested that resources are consistently switched from longer term and more time-consuming dimensions of the planning service, in order to maintain development control throughput and meet national time targets (DTLR, 2002, pp. 8–9). In this case, the pressure brought to bear by the national targets was clearly distorting practice locally.

Later evidence indicates that in an attempt to address the national resource crisis in planning, the introduction of financial incentives from government tied to planning authorities meeting their time targets only distorted the process further (see Chapter 5). The figures from the Planning Inspectorate suggest that numbers of appeals have been driven up dramatically as applications are rejected rather than becoming the subject for negotiation, in order for authorities to meet the targets (Arnold, 2003). The result may very well be a longer planning process for many as more aspects are fought, although a shorter process on paper as measured against the performance targets.

It may be argued, however, that a degree of distortion is acceptable if the overall effect is an improvement against an objective that is considered so important that it outweighs all others (i.e. reducing the national incidence of deaths by cancer in the case of the health service). Others might argue that distortion is acceptable if the overall impact (accounting for any distortion) is positive (i.e. if national levels of literacy improve in the case of primary education). It is likely therefore that the way different objectives are balanced will be the most important factor; for example, the pursuit of a speedy planning process (one dimension of quality) versus one that delivers more predictable and considered decisions (among other important dimensions). In a properly resourced service, it may also be possible to deliver on both objectives and thereby minimise any distortion.

Thus distortion is a consequence both of the process of performance measurement (i.e. how a target is devised and expressed), and of the broader context in which it is interpreted and implemented.

Measuring quality

This brings the discussion to the third question, which put another way asks: How can a non-distortionary, objective and comprehensive system be developed in order to measure the quality of planning? Or, perhaps more realistically, how can a less distortionary, more objective and more comprehensive system be devised, given the considerable conceptual and practical difficulties of the task?

This is important in order to avoid the situation whereby those aspects of the planning service which are difficult to measure are devalued, simply because they do not lend themselves to easily measurable (for which read quantifiable) criteria. In this regard, the House of Commons Public Services Committee (1996) has described the state of performance measurement across the public sector as ‘data rich and information poor’, in part because the performance of most public services is so complex to measure, and as a result performance measurement is often limited to those aspects that can be measured easily and expediently.

Examining this conundrum, and in particular the processes, impact and future of performance measurement in planning, provided the basis for the research project on which this book is based. It draws from and relates to a profound and complex discussion about how the quality of spatial planning per se can be measured reliably and usefully. These questions have been recognised by governments across the world and are beginning to be addressed in policy developments (see Chapters 5 and 8). However, the fundamentals of performance measurement in planning are by no means well understood, let alone practised, and the publication of national performance measures for ‘quality in planning’, while putting some sort of agenda on the table, may not aid local planning authorities along the road to developing more useful performance measurement systems locally. This is because the business of measuring quality is extremely complex, and most local authorities do not have the resources to spare to develop anything more than the most basic measures.

It is the purpose of this book to address the complexities and—as far as possible—to cut through the tangled web of thinking that has dogged performance (or quality1) measurement in planning specifically, but also by association in the public sector at large.

The remainder of this chapter introduces the research, its aim, objectives and methodology, before turning to the book itself and discussing its structure and utility.

The research—measuring quality in planning

The project was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), and undertaken between February 2002 and May 2003. The research aim was constructed as follows:

In a context where the ‘value added’ by public services needs to be measured and proven, and where those aspects of the public service remit which cannot be directly measured can—as a result—be undervalued, the research aims to explore if and how the output quality of the planning system might be appropriately measured, and therefore, if and how existing systems of measurement can be tailored to better reflect such concerns.

The aim was broken down into five research objectives:

- To explore best practice nationally and internationally in the use of ‘quality measurement systems’ in the planning process.

- To explore the relationship between quality outcomes and quality processes as delivered through local planning services.

- To examine how—if at all—outcomes and processes can be measured and, if appropriate, weighted.

- To therefore ask how legitimate, feasible and effective it is to measure quality outcomes (i.e. better designed, more sustainable environments).

- To make recommendations on how the developing performance management regime in the UK (and elsewhere) can better incorporate a fundamental concern for outcome quality concerns in planning (and other related) services.

To ensure systematic analysis of th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Part One: Planning for quality

- Part Two: Measuring quality

- Appendix 1: The quality tools

- Appendix 2: Analysis of policy framework content in the case study authorities

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Measuring Quality in Planning by Matthew Carmona,Louie Sieh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architettura & Pianificazione urbana e paesaggistica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.