eBook - ePub

Women On Ice

Feminist Responses to the Tonya Harding/Nancy Kerrigan Spectacle

This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women On Ice

Feminist Responses to the Tonya Harding/Nancy Kerrigan Spectacle

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The attack on Nancy Kerrigan at the 1994 U.S. Figure Skating Championships set the stage for a Winter Olympics spectacle: Tonya versus Nancy. Women on Ice collects the writings of a diverse group of feminists who address and question our national obsession with Tonya and Nancy and what this tells us about perceptions of women in twentieth century America.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Women On Ice by Cynthia Baughman, Cynthia Baughman, Cynthia Baughman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 > |  | < Jane Feuer |

Nancy and Tonya and Sonja

The Figure of the Figure Skater in

American Entertainment

Introduction

An unanticipated by-product of the 1994 Lillehammer Olympics was the video re-release of eight films from the star of the previous Norwegian Olympic games, Sonja Henie (1912–1969). Although her films had been shown regularly on AMC and I specialize in Hollywood musicals and have always had a special interest in figure skating, I never thought to include them in a study of the Hollywood musical. Even though I took a keen interest in the Nancy and Tonya brouhaha, having followed both their careers for many years previously, it never occurred to me to think about Sonja Henie at all until I was asked to contribute to this book at the same time as the Henie films became available from Fox video. By coincidence (or, in the case of Fox, planning), I viewed Sonja Henie's black and white Fox films of the late thirties and early forties at the same time as the Lillehammer Olympics and the attendant tabloid coverage of the Nancy and Tonya debacle. The coincidence provided me with the occasion for bringing to bear on figure skating many of my concerns as a film and television scholar: the ice-skating film as musical; the difference between the studio system's and contemporary media's constructions of celebrity; and even the meaning of skating itself as a longstanding form of popular entertainment that spans the studio and the contemporary eras and that combines elements of sport with elements of dance, in the process attempting to merge two very contradictory ideological fields (not least because sport is coded as masculine in our society; dance as feminine).

Sonja Henie was, arguably, the most fabulously successful figure skater ever. She maintained a public skating career from the age of eleven to her death at the age of fifty seven. She was thought at one time to be the richest woman in Hollywood; she had a carefully constructed Hollywood star image, spawned all kind of commodity tie-ins, became the subject of a tell-all “Mommie Dearest” exposé some fifteen years after her demise, and remains virtually unknown to most Americans under the age of fifty. Thus she's the perfect example of a figure skater who rose and fell in the public's estimation, and the prototype for the kind of media frenzy surrounding Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding today.1

I want to use Sonja to place in historical perspective the image of the star figure skater. Eventually, I want to make the argument that tabloid TV exposure is better for Tonya's image than for Nancy's. But I want to do this through an analysis of Sonja Henie in particular and figure skating stardom in general. For I believe it is not the case that skating is a throwback, old-fashioned, wholesome form of entertainment like Big Band music or state fairs. Just as the construction of stardom has evolved through changes in media, so has the image of the skater as it moves from film portrayals and live spectacles in the studio era to television coverage and a different kind of live spectacle in the 1990s. Although it is not my subject, one can note the rise in status of the sexy male figure skating star to teenybop idol as just one indication that we have moved into what might be called a “postmodern” era in skating, one that contrasts with the traditional imagery of a holiday on ice. I will argue that the Nancy and Tonya affair is also symptomatic of the emergence of figure skating as a postmodern form of entertainment in the age of tabloid TV.

The Figure Skater as Star

I would like to begin with a simple yet elegant proposition culled from many years of studying show business: a star's image has to be constructed before it can be deconstructed. Sonja Henie, for example, received some bad publicity during the War because of her friendship with Hitler, but her 1940 memoir Wings on my Feet totally mystifies her own life story. Similarly, a star such as Judy Garland spent years building up her MGM image before her later career made “Over the Rainbow” into a tragic ballad about her own life. Star image construction in the studio era was like that. A vast publicity machine existed not to drag stars through the dirt but rather to glorify them and cover up their alcoholism, their promiscuous sexual escapades, their homosexuality, or even their working-class origins. For both Joan Crawford and Sonja Henie, exposés referred to as “mommie dearest” and “sister dearest” were published many years after their deaths.

This kind of mystification of stars is no longer possible in today's world of images nor is it considered desirable. Tabloid TV tends not to have time for the construction process, or, as in the case of Nancy Kerrigan, the build-up is compacted. According to a cartoon in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette entitled “The Nancyometer,” all three stages of Nancy's notoriety—the attack, the Olympics, and the fallout—occurred between January 4 and Feb. 27, 1994. Nancy had about a month to establish her star image in the public eye before the process of deconstruction began with the bitchy remarks about Oksana's crying, the surly visit to Disneyworld, and the satirical demystification of Nancy's image on Saturday Night Live on March 12,1994. In the world of postmodern star image construction and deconstruction, Nancy didn't stand a chance.

Of what, typically, does a figure skater's image consist? The conventional image is of a child-like fairy-tale princess. Sonja Henie, for instance, although about twenty-five when she began her U.S. film career, looked far more like Twentieth Century Fox's other major female star of the 1930s, Shirley Temple, than she did like an adult movie star.

Shirley and Sonja

In fact, for the 1938 box office year, Shirley and Sonja were the number one and two female stars, respectively. Both had blond curls, round faces and dimples. The resemblance was terrifying. Sonja herself had been a child sports star in Norway, winning her first championship at the age of eleven and her first Olympics at sixteen. In her films, Sonja often starts out as a naive Scandinavian or Swiss in folk costumes with see-through puff sleeves or in traditional village costumes. In Sun Valley Serenade, her best-remembered film (not because of her but because of the Glen Miller songs), she plays a refugee adopted by the hero. Thinking she will be a small child, he decorates her room with dolls and toys. When the child-woman arrives, aside from her sexual aggressiveness, one could well imagine her playing with those dolls. Later, especially in those films where she becomes a skating star, she becomes more sophisticated. Indeed her last film at Fox, Wintertime, gives us a darker-haired, slimmer-faced Sonja who dresses like Joan Crawford, skates like a dream, speaks English, and even acts like a grown-up. Wintertime would be her last and least successful Fox film. But the child-star image is never truly demystified in her films. This child-star tradition continues today with Oksana Baiul and Michelle Kwan, giving us the best of both sporting and celebrity traditions: the child star and the superathelete—Shirley Temple on ice. In this sense figure skating today is a direct descendent of traditional entertainment practices embodied in the Ice Capades and in classic Hollywood musicals. This is true both in terms of narrative form and processes of star image construction.

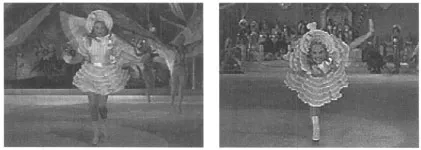

“Alice in Wonderland” from My Lucky Star (1938)

When traditional figure skaters do films or TV specials, they tend to be cast in fairy-tale narratives. Sonja would often do the first skating “number” in a film at a village festival; her later skating spectaculars would take the form of children's stories such as Alice in Wonderland as often as they would employ sophisticated sequined show business styles.

Similarly, Olympian Carol Heiss would be cast as an innocent, virginal Snow White, as if to cushion the power of her skating. As late as 1994, Dorothy Hamill, by now a mature woman, was cast as Cinderella in a skating TV special designed to coincide with Lillehammer. Entitled, Cinderella: Frozen in Time, the April 16,1994 broadcast took the form of a narrated fairy tale on ice performed at a rink for a live audience with the usual balletic choreography and virginal costuming. Oksana's 1994 Olympic gold performance as the Swan had its precedent in a number Sonja frequently performed in ice shows, the Dying Swan, a balletic rendition Sonja claimed to have stolen from the famed ballerina Anna Pavlova. Sonja's feathered costume (to judge from photos in her 1940 book) bore a striking resemblance to the one Oksana wore at the Olympics. This is the stereotyped image of the Russian ballerina as bird-like creature, an image easily parodied in the opening segment of the Nancy-hosted Saturday Night Live when a similarly clad Russian ballerina appeared in the audience in drag.

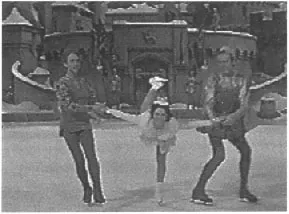

Showing her maturity, Dorothy Hamill still enacts the myth

of the fairy princess as she impersonates Cinderella.

Carol Heiss as Snow White

The traditional figure skater, then, is portrayed as a wounded bird, a child or a fairy tale princess. If we look at the conceptual opposition which structures figure skating and its media coverage—artistry vs. athleticism— (brought out in several other essays in this book), we can see that the traditional figure skating star image comes down heavily on the “artistry” side. If figure skating is a combination of dance and sport, the traditional image as conveyed by Sonja Henie emphasizes dance and minimizes athleticism in order to present a child-like version of femininity to the public. As in ballet, such femininity can only be an illusion requiring tremendous strength to perpetuate.

Dorothy Hamill as Cinderella

In this sense neither Nancy nor Tonya fit the traditional image, but Oksana did. Nancy is considered an ‘artistic’ skater, but still more ‘athletic’ than Oksana. According to an intricate explanation given on TV (explained in full in Appendix 2 of this book), they actually tied in the judges’ numerical votes. Nancy lost on a technicality because the artistic scores (in which Oksana was marginally better) were given final preference over the technical scores. In terms of “artistry” which is not quite but almost synonymous with “femininity,” Oksana is to Nancy as Nancy is to Tonya. One might say that the entire Lillehammer contest ended by glorifying and reestablishing the most traditionally feminine mode of the figure skater as ballerina. Oksana has the body of Russian ballerina Natalia Makarova which was considered the perfect classical ballet body. Yet there is a world of difference between the body of Oksana and the body of, say, Sonja Henie, although both in their ways present an infantalized version of a woman's body. In the one case there is the “waif look” currently popularized in the sphere of fashion by model Kate Moss; in the other case, the flat chest and huge powerful thighs of an athlete contrasting with that round-faced blond doll of a head. In a sense, Sonja did more to foreground the contradiction between athleticism and artistry than Oksana does today, at least in terms of body language. This is where the idea that, as one TV commentator put it, “Tonya skates like a man,” becomes interesting, because, compared to Oksana, Nancy now ‘skates like a man’ too. Even when she skates out to her position on the ice, she is very “tomboyish.” I believe ‘Hepburnesque’ was the term used by TV commentators to describe this quality. This appellation doesn't jive with her being a “perfect lady” and “the girl next door.” In one tabloid tape, we see her striding into the rink after her “attack.” She is doing a little jig—a real jock. From my sixth row center position at the skating exhibition, I could see Nancy sneaking out to the edge of the rink to begin her performance; she moved more like Bonnie Blair than like a Russian ballerina. Nancy's skating is praised for its “elegant line,” a balletic quality to be sure but one less pliantly feminine than Oksana's extreme flexibility. No American skating star has approached the balletic apex of femininity that Oksana occupies today and that Michelle Kwan promises to occupy in the future. In terms of feminine body images, competitive skating has regressed rather than progressed.

Before she spoke on TV, it was easier to perpetuate Nancy's image as an ice princess. I remember seeing her in competition prior to the 1992 Olympics and seeing her live in the 1992 traveling exhibition of World and Olympic champions. At that time I found her skating elegant and mysterious, enhanced as it was by her beauty. I saw her fall many times but I never heard her talk until after the attack. Ice princesses don't talk to the press or they talk with a charming and child-like foreign accent or with the aid of a male interpreter (Sonja, Oksana). Ballerinas don't talk. And the old studios knew that fairy tale princesses shouldn't talk without a script or without the presence of a publicist. Nancy's mystique could only be ruined by tabloid coverage.

Figure Skating Films as Fairy-tale Musicals

In addition to their narrative prototypes and the child-like femininity they foster, figure skating films are fairy tales in yet another sense: they meet all of the criteria for the fairy-tale subgenre of musicals detailed at length by Rick Altman in The American Film Musical. Of Sonja's Fox films, only one falls entirely outside of the fairy-tale model and that one was re-released as Irving Berlin's Second Fiddle, not as a Sonja Henie film per se. This 1939 film was already a parody of the backstage musical or what Altman calls the show musical. Featuring a behind-the-screen setting, it satirized the contemporary search for Scarlett O'Hara by casting Sonja as a skating school teacher who becomes a star and gets involved with her studio's publicist (played by Sonja's real life lover Tyrone Power). Even in this sophisticated story, most of the skating takes place on a little pond in Minnesota accompanied by a phonograph. There is even a children's skating number early in the film when Sonja is still a schoolteacher (presumably she teaches gym).

Before I go on to discuss them as fairy-tale musicals, perhaps I should say a few words as to why I consider these figure skating spectaculars to be musicals at all. With Altman, I believe that the Hollywood musical is defined by a dual-focus between narrative and numbers. This opposition is one of structure, not content. Therefore a film with a comic romance plot that alternates story portions with nightclub numbers and skating numbers and that resolves in successful coupling is a musical, just as MGM films which used Esther Williams water ballets as numbers were musicals. Figure skating is the content of the show that is put on, but structurally it occupies the same space as dancing does in other musical films.

Sonja Henie's other Fox films constitute the most important group of fairy-tale musicals outside of the MacDonald-Chevalier-Lubitsch-Mamoulian films at Paramount in the late 1920s to early 1930s, the Astaire-Rogers series at RKO throughout the 1930s, and Vincente Minnelli's important fairy-tale musicals at MGM in the late 1940s and 1950s The Fir ate, Yolanda and the Thief, An American in Paris, Gigi). According to Altman, the fairy-tale musical is characterized by its setting in an imaginary kingdom which is thrown into chaos through royal love problems. The governmental plot parallels the love story. This is where the link to actual fairy tales is clearest, and even Snow White and the Three Stooges fits the pattern perfectly. The Sonja Henie film which most closely approximates the early Paramount fairy-tale musicals is Thin Ice (1937), in which Sonja plays a skating instructress in a large Swiss hotel who romances a prince unbeknownst to her. The scandal of the prince falling for a lowly hotel employee throws both the government of his imaginary kingdom and the kingdom of the hotel into chaos. Many of the other Fox films are closer to the Fred and Ginger films in which a hotel or an ocean liner substitutes for a literal kingdom. Of Sonja's Fox films, One in a Million, Thin Ice, Sun Valley Serenade and Wintertime are set at resorts or hotels.

For Altman, the fairy-tale musical bears a close link to its contemporary Hollywood genre, the screwball comedy. Indeed many of Sonja's films feature elements of screwball romance. These are the films in which Sonja talks too much (but never while skating) in her charmingly accented English, as in Sun Valley Serenade (1941) or Iceland (1942) in both of which she attempts to trick co-star John Payne into marriage. Happy Landings (1938), filmed at the height of the screwball craze, sustains a madcap plot which culminates in a double wedding involving Sonja, Don Ameche, Caesar Romero and Ethel Merman followed by a coda in which all four lovers skate together as Sonja pulls them in a conga line.

Sonja skates on a big white rink in Everything Happens at Night (1939)

Finally, the Sonja Henie Fox films alternate a dream world with a “real” world, the thematic center of the fairy-tale type. There is usually a contrast between the more realistic (although not very realistic) realm of the narrative and the spectacular world of the skating interludes. Although in some ways the skating numbers mimic the spectacle of Busby Berkeley production numbers, in other ways they represent a dream world expressed in the castles and palaces of the Paramount films and in the big white sets of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films.

Even more representative of the rea...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Skating

- Part II Pairs

- III Television Spectacles

- Part IV Fantasies

- Appendix I Ellyn Kestnbaum

- Appendix II Ellyn Kestnbaum

- List of Contributors