This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

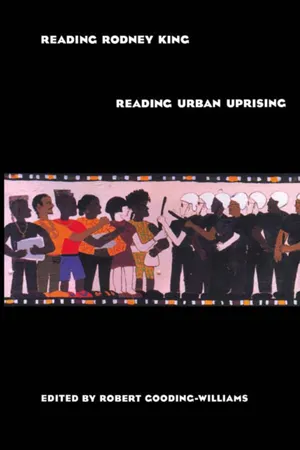

Reading Rodney King/Reading Urban Uprising

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Reading Rodney King/Reading Urban Uprising keeps the public debate alive by exploring the connections between the Rodney King incidents and the ordinary workings of cultural, political, and economic power in contemporary America. Its recurrent theme is the continuing, complicated significance of race in American society. Contributors: Houston A. Baker, Jr.; Judith Butler; Sumi K. Cho; Kimberle Crenshaw; Mike Davis; Thomas L. Dumm; Walter C. Farrell, Jr.; Henry Louis Gates, Jr.; Ruth Wilson Gilmore; Robert Gooding-Williams; James H. Johnson, Jr.; Elaine H. Kim; Melvin L. Oliver; Michael Omi; Gary Peller; Cedric J. Robinson; Jerry Watts; Cornel West; Patricia Williams; Rhonda M. Williams; Howard Winant.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Reading Rodney King/Reading Urban Uprising by Robert Gooding-Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Beating Black Bodies

1

Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia

Judith Butler

The defense attorneys for the police in the Rodney King case made the argument that the policemen were endangered, and that Rodney King was the source of that danger. The argument they made drew from many sources, comments he made, acts he refused to perform on command, and the highly publicized video recording taken on the spot and televised widely before and during the trial. During the trial, the video was shown at the same time that the defense offered a commentary, and so we are left to presume that some convergence of word and picture produced the “evidence” for the jurors in the case. The video shows a man being brutally beaten, repeatedly, and without visible resistance; and so the question is, How could this video be used as evidence that the body being beaten was itself the source of danger, the threat of violence, and, further, that the beaten body of Rodney King bore an intention to injure, and to injure precisely those police who either wielded the baton against him or stood encircling him? In the Simi Valley courtroom, what many took to be incontrovertible evidence against the police was presented instead to establish police vulnerability, that is, to support the contention that Rodney King was endangering the police. Later, a juror reported that she believed that Rodney King was in “total control” of the situation. How was this feat of interpretation achieved?

That it was achieved is not the consequence of ignoring the video, but, rather, of reproducing the video within a racially saturated field of visibility. If racism pervades white perception, structuring what can and cannot appear within the horizon of white perception, then to what extent does it interpret in advance “visual evidence”? And how, then, does such “evidence” have to be read, and read publicly, against the racist disposition of the visible which will prepare and achieve its own inverted perceptions under the rubric of “what is seen”?

In the above, without hesitation, I wrote, “the video shows a man being brutally beaten.” And yet, it appears that the jury in Simi Valley claimed that what they “saw” was a body threatening the police, and saw in those blows the reasonable actions of police officers in self-defense. From these two interpretations emerges, then, a contest within the visual field, a crisis in the certainty of what is visible, one that is produced through the saturation and schematization of that field with the inverted projections of white paranoia. The visual representation of the black male body being beaten on the street by the policemen and their batons was taken up by that racist interpretive framework to construe King as the agent of violence, one whose agency is phantasmatically implied as the narrative precedent and antecedent to the frames that are shown. Watching King, the white paranoiac forms a sequence of narrative intelligibility that consolidates the racist figure of the black man: “He had threatened them, and now he is being justifiably restrained.” “If they cease hitting him, he will release his violence, and now is being justifiably restrained.” King’s palm turned away from his body, held above his own head, is read not as self-protection but as the incipient moments of a physical threat.

How do we account for this reversal of gesture and intention in terms of a racial schematization of the visible field? Is this a specific transvaluation of agency proper to a racialized episteme? And does the possibility of such a reversal call into question whether what is “seen” is not always already in part a question of what a certain racist episteme produces as the visible? For if the jurors came to see in Rodney King’s body a danger to the law, then this “seeing” requires to be read as that which was culled, cultivated, regulated—indeed, policed—in the course of the trial. This is not a simple seeing, an act of direct perception, but the racial production of the visible, the workings of racial constraints on what it means to “see.” Indeed, the trial calls to be read not only as instruction in racist modes of seeing but as a repeated and ritualistic production of blackness (a further instance of what Ruth Gilmore, in describing the video beating, calls an act of “nation building”). This is a seeing which is a reading, that is, a contestable construal, but one which nevertheless passes itself off as “seeing,” a reading which became for that white community, and for countless others, the same as seeing.

If what is offered here over and against what the jury saw is a different seeing, a different ordering of the visible, it is one that is also contestable—as we saw in the temporary interpretive triumph of the defense attorneys’ construal of King as endangering. To claim that King’s victimization is manifestly true is to assume that one is presenting the case to a set of subjects who know how to see; to think that the video “speaks for itself” is, of course, for many of us, obviously true. But if the field of the visible is racially contested terrain, then it will be politically imperative to read such videos aggressively, to repeat and publicize such readings, if only to further an antiracist hegemony over the visual field. It may appear at first that over and against this heinous failure to see police brutality, it is necessary to restore the visible as the sure ground of evidence. But what the trial and its horrific conclusions teach us is that there is no simple recourse to the visible, to visual evidence, that it still and always calls to be read, that it is already a reading, and that in order to establish the injury on the basis of the visual evidence, an aggressive reading of the evidence is necessary.

It is not, then, a question of negotiating between what is “seen,” on the one hand, and a “reading” which is imposed upon the visual evidence, on the other. In a sense, the problem is even worse: to the extent that there is a racist organization and disposition of the visible, it will work to circumscribe what qualifies as visual evidence, such that it is in some cases impossible to establish the “truth” of racist brutality through recourse to visual evidence. For when the visual is fully schematized by racism, the “visual evidence” to which one refers will always and only refute the conclusions based upon it; for it is possible within this racist episteme that no black person can seek recourse to the visible as the sure ground of evidence. Consider that it was possible to draw a line of inference from the black male body motionless and beaten on the street to the conclusion that this very body was in “total control,” rife with “dangerous intention.” The visual field is not neutral to the question of race; it is itself a racial formation, an episteme, hegemonic and forceful.

In the white world the man of color encounters difficulties in the development of his bodily schema. Consciousness of the body is solely a negating activity. It is a third-person consciousness. The body is surrounded by an atmosphere of certain uncertainty. I know that if I want to smoke, I shall have to reach out my right arm and take the pack of cigarettes lying at the other end of the table. The matches, however, are in the drawer on the left, and I shall have to lean back slightly. And all of these movements are made not out of habit but out of implicit knowledge. A slow composition of my self as a body in the middle of a spatial and temporal world—which seems to be the schema…. Below the corporeal schema I had sketched [there is] a historico-racial schema. The elements I had used had been provided for me … by the other, the white man, who had woven me out of a thousand details, anecdotes, stories. I thought that what I had in hand was to construct a physiological self, to balance space, to localize sensations, and here I was called on for more.“Look, a Negro!” It was an external stimulus that flicked over me as I passed by. I made a tight smile.“Look, a Negro!” It was true. It amused me.“Look, a Negro!” The circle was drawing a bit tighter.I made no secret of my amusement.“Mama, see the Negro! I’m frightened!” Frightened!”Frightened! Now they were beginning to be afraid of me. I made up my mind to laugh myself to tears but laughter had become impossible.1

Frantz Fanon offers here a description of how the black male body is constituted through fear, and through a naming and a seeing: “Look, a Negro!” where the “look” is both a pointing and a seeing, a pointing out what there is to see, a pointing which circumscribes a dangerous body, a racist indicative which relays its own danger to the body to which it points. Here the “pointing” is not only an indicative, but the schematic foreshadowing of an accusation, one which carries the performative force to constitute that danger which it fears and defends against. In his clearly masculinist theory, Fanon demarcates the subject as the black male, and the Other as the white male, and perhaps we ought for the moment to let the masculinism of the scene stay in place; for there is within the white male’s racist fear of the black male body a clear anxiety over the possibility of sexual exchange; hence, the repeated references to Rodney King’s “ass” by the surrounding policemen, and the homophobic circumscription of that locus of sodomy as a kind of threat.

In Fanon’s recitation of the racist interpellation, the black body is circumscribed as dangerous, prior to any gesture, any raising of the hand, and the infantilized white reader is positioned in the scene as one who is helpless in relation to that black body, as one definitionally in need of protection by his/her mother or, perhaps, the police. The fear is that some physical distance will be crossed, and the virgin sanctity of whiteness will be endangered by that proximity. The police are thus structurally placed to protect whiteness against violence, where violence is the imminent action of that black male body. And because within this imaginary schema, the police protect whiteness, their own violence cannot be read as violence; because the black male body, prior to any video, is the site and source of danger, a threat, the police effort to subdue this body, even if in advance, is justified regardless of the circumstances. Or rather, the conviction of that justi-fication rearranges and orders the circumstances to fit that conclusion.

What struck me on the morning after the verdict was delivered were reports which reiterated the phantasmatic production of “intention,” the intention inscribed in and read off Rodney King’s frozen body on the street, his intention to do harm, to endanger. The video was used as “evidence” to support the claim that the frozen black male body on the ground receiving blows was himself producing those blows, about to produce them, was himself the imminent threat of a blow and, therefore, was himself responsible for the blows he received. That body thus received those blows in return for the ones it was about to deliver, the blows which were that body in its essential gestures, even as the one gesture that body can be seen to make is to raise its palm outward to stave off the blows against it. According to this racist episteme, he is hit in exchange for the blows he never delivered, but which he is, by virtue of his blackness, always about to deliver.

Here we can see the splitting of that violent intentionality off from the police actions, and the investment of those very intentions in the one who receives the blows. How is this splitting and attribution of violent intentionality possible? And how was it reproduced in the defense attorneys’ racist pedagogy, thus implicating the defense attorneys in a sympathetic racist affiliation with the police, inviting the jurors to join in that community of victimized victimizers? The attorneys proceeded through cultivating an identification with white paranoia in which a white community is always and only protected by the police, against a threat which Rodney King’s body emblematizes, quite apart from any action it can be said to perform or appear ready to perform. This is an action that the black male body is always already performing within that white racist imaginary, has always already performed prior to the emergence of any video. The identification with police paranoia culled, produced, and consolidated in that jury is one way of reconstituting a white racist imaginary that postures as if it were the unmarked frame of the visible field, laying claim to the authority of “direct perception.”

The interpretation of the video in the trial had to work the possible sites of identification it offered: Rodney King, the surrounding police, those actively beating him, those witnessing him, the gaze of the camcorder and, by implication, the white bystander who perhaps feels moral outrage, but who is also watching from a distance, suddenly installed at the scene as the undercover newsman. In a sense, the jury could be convinced of police innocence only through a tactical orchestration of those identifications, for in some sense, they are the white witness, separated from the ostensible site of black danger by a circle of police; they are the police, enforcers of the law, encircling that body, beating him, once again. They are perhaps King as well, but whitewashed: the blows he suffers are taken to be the blows they would suffer if the police were not protecting them from him. Thus, the physical danger in which King is recorded is transferred to them; they identify with that vulnerability, but construe it as their own, the vulnerabilty of whiteness, thus refiguring him as the threat. The danger that they believe themselves always to be in, by virtue of their whiteness (whiteness as an epi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One Beating Black Bodies

- Part Two Acquitting White Brutality

- Part Three Assaulting America: A Political Economy Begets Ruin

- Part Four On the Streets of Los Angeles

- Part Five Ideology, Race, and Community

- Part Six The Fire This Time

- Index

- Contributors