![]()

1

Butoh Shapeshifters

Kaze Daruma: The Origins of Butoh

We begin with a definition: In Japan, a Daruma is a limbless figure (or doll) weighted so that it bounces back when knocked over. It is a symbol of persistence leading to success. Daruma is also an abbreviation for Bodhidharma, a mythical Middle Eastern priest said to have carried Buddhist practice and teachings to China about 500 BC. From there, the teachings traveled to Korea in AD 372 and eventually to Japan. Prince ShMtoku proclaimed it the state religion of Japan in AD 594.

In February of 1985, the night before the Tokyo Butoh Festival 85 and one year before his death, Hijikata Tatsumi gave a lecture at Asahi Hall called Kaze Daruma (Wind Daruma), quoting an ancient Buddhist priest, Kyogai, and then telling stories of harsh winters in his homeland of Akita where darumas come rolling in the wind with their bones on fire. When the Wind Daruma stands at the door and goes into the parlor, “this is already butoh,” Hijikata says. He remembers how as a child in the country of snow and mud he was made to eat pieces of half-burnt coal, which were supposed to cure him of “peevishness.” Then he spoke about Showa the third [1928], the year of his birth and harbinger to war “when the Asian sky was gradually, eerily becoming overcast” (Hijikata 2000d: 74). The Showa period of Japanese history [1926–1988] coincides with Hijikata’s life span [1928–1986]. The Japanese era designation indicating an emperor’s life span started in 645, and is used in conjunction with the Christian calendar.

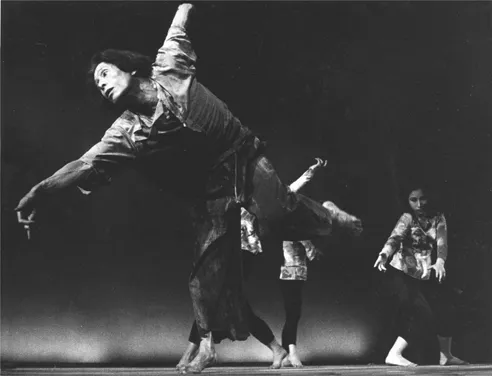

Figure 1.1 Hijikata Tatsumi in Calm House. Photograph by Torii Ryozen. Courtesy the Hijikata Tatsumi Archive

In his lifetime, Hijikata witnessed Japan’s military build up preceding World War II and its post-war Westernization. He experienced Japan’s defeat and drastic changes in political and social values – growing to extremes in the 1960s. No area of Japanese life was immune to the political shifts taking place around the world at this time. In 1968, the year of Hijikata’s dance Revolt of the Flesh, Japanese youths, like those in America and Europe, took to the streets in unprecedented numbers. Hijikata’s theatrical revolution, while not a declared movement of The New Left, nevertheless resembled the politics of public protest. Meanwhile, under American protectionism after the war, economic growth incomparable in world history placed Japan as one of the world’s major economic powers.

This is the historical crucible that tested Hijikata and marked his butoh. During the war, he languished as a lonely adolescent in a house with a lot of empty rooms with his five older brothers off in the army (2000d: 73). He began his study of modern dance in 1946 during the difficult aftermath of occupation, as Japan recovered from near collapse with America’s fire bombing of Tokyo claiming as many lives as the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; at least 300,000 were killed, and that many more were doomed. Hijikata would eventually originate a radically new form of dance theater, Ankoku Butoh (darkness dance), gestating in the early post-war era and finally coming to attention during the global upheavals and political riots of the 1960s. His dance, now known simply as butoh (dance step), flourished underground in Tokyo, and eventually resounded around the globe in dance, theater, visual art, and photography.

Rustic and contemporary, as Western as it is Eastern, the butoh legacy of Hijikata spans cultural divides. Honed from personal and inter-cultural resources, butoh mines identity, even as it reaches beyond its local beginnings. Retention of identity amid synthesis has been the Japanese way for centuries. Likewise, it is a butoh strategy – growing at first from Hijikata’s dissatisfaction with Western ballet. He finally understood in the 1950s after studying ballet for several years that his own body was not suited to this Western form. He was not innately plastic and flowing in ballet, but rather bow-legged and tense. In time, he was to turn this liability into an asset, creating out of the well of his frustration; turning first to the Japan of his rural roots, Hijikata began to work with the givens of his own body.

He also developed an absurdist, surrealist philosophy that flaunted societal taboos. His first experiment in butoh, Kinjiki, performed for the Japanese Dance Association ‘New Face Performance’ in 1959 in Tokyo, was based on the homoerotic novel Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors) by Mishima Yukio (1951) and featured a chicken being squeezed between the legs of Ohno Yoshito, the very young son of Ohno Kazuo (b. 1906). The elder Ohno later became a butoh icon and one of the most treasured Japanese performers of the twentieth century. The stage was dark and the dance was short, but its sexual message shocked the All Japan Art Dance Association (the name was later changed to Japan Dance Association). Some accounts say Hijikata was expelled from the association over this dance, but in fact he voluntarily resigned along with Ohno and their friend Tsuda. Hijikata’s early subversive themes were drawn from the writings of Jean Genet that he read in the mid-1950s – The Thief’s Journal (1949) and Our Lady of Flowers (1944) – just translated into Japanese. He even performed for a while under the stage name of Hijikata Genet. In his one program note for Kinjiki, Hijikata says, “I studied under Ando Mitsuko, consider Ohno Kazuo a brother, and adore Saint Genet” (Hijikata 1959).

Goda Nario wrote of Kinjiki:

It made those of us who watched it to the end shudder, but once the shudder passed through our bodies, it resulted in a refreshing sense of release. Perhaps there was a darkness concealed within our bodies similar to that found in Forbidden Colors and which therefore responded to it with a feeling of liberation.

(Goda 1983: unpaginated)

Hijikata’s work eventually gained audiences in the Tokyo avant-garde, as he drew inspiration from such diverse sources as the films of Kurosawa Akira – Yoidore Tenshi (The Drunken Angel) – and European surrealist writers.

Hijikata’s Butoh

In 1968, Hijikata choreographed one of his most quoted works – Hijikata Tatsumi to nihonjin: Nikutai no hanran (Hijikata Tatsumi and the Japanese: Rebellion of the Body). This work, also known as Revolt of the Flesh, marks Hijikata’s shamanistic descent to darkness and clearly establishes a new form of dance rooted in his memories of Tohoku, the rustic landscape of his childhood in a poor district of Japan. In Revolt, Hijikata casts spells as his body morphs through shocking juxtapositions, twitching trance-like in a G-string beside a dangling rabbit on a pole. He gyrates and provokes with a large strapped-on golden penis, dances in a dress, swings on a rope with white cloth trailing and wrapping his hips, then surrenders himself, Christ-like, in crucifixion. Over ten years on the fringes of Tokyo’s postwar modernization, Hijikata creates a radically new form of Dance Theater, merging the universal spectacle of the naked human body, stooped postures of old people in his homeland, the pain of his childhood, and his distrust of Western ways as they enter Japan through the American occupation after World War II (see Fraleigh 2005: 328). “One thing for sure,” he writes in ‘To Prison’ in 1961, “I will no longer be cheated by a bad check called democracy…. Is there any greater misery than entrusting a dream to a reality from which one will sometime have to wake?” (2000b: 43).

Butoh gained a following in Japan and internationally as Hijikata’s repertoire and his collaborators expanded. Through his association with Ohno Kazuo and his female protégé, Ashikawa Yoko, butoh moved from a phallocentric aesthetic to a full spectrum dance form with permeable boundaries. In 1954 the young Hijikata began lifetime collaboration with Ohno who was already middle-aged and a leader of modern dance in Japan. Ohno had studied with Eguchi Takaya who in turn was a pupil of Mary Wigman in Dresden, Germany before World War II, but Ohno turned away from Western modern dance through his work with Hijikata. Through his world tours and generous nature, Ohno won international audiences while assimilating the other, dancing Admiring La Argentina in a flamenco style and French painter Monet’s Water Lilies in an impressionist one. Ohno performed his poetic butoh around the world. Hijikata never left Japan (Fraleigh 2005: 328).

Ashikawa became the third founder of butoh through her work with Hijikata beginning in 1966. Exploring the watery soma of infancy and bodily discovery, she flowed through Hijikata’s word imagery in poetic streams, pouring her body through Hijikata’s profuse kinesthetic images – his butoh-fu. He numbered and classified these; thus, while butoh remains a poetic, intuitive form of theater, it also has structure through Hijikata’s imagistic and verbal notation for motivating dance (see Stewart on structure of butoh, 1998: 45–8). Today there are continuing themes of butoh, reminders of Hijikata, scattered around the globe.

Figure 1.2 Ashikawa Yoko in, Lover of Mr Bakke choreographed by Hijikata. Photograph by Onozuka Makoto. Courtesy the Hijikata Tatsumi Archive

Nature, Mud, and Butoh Morphology

Tsuchi kara umareta (I come from the mud).

Hijikata Tatsumi

Butoh can be traced to at least three major sources: Hijikata’s memorial to mud and wind in his published speech ‘Kaze Daruma’ outlines his somatic intimacy with nature, and casts butoh first as a unique type of performed ecological knowledge with agricultural roots. Secondly, Hijikata’s development of butoh in the East/West atmosphere of Tokyo as it modernized after the war lends his dance political, cross-cultural, and urban juxtapositions (Fraleigh 2005: 327). Thirdly, Hijikata’s butoh connects to the Japanese traditional arts, especially early Kabuki of the Edo period, in which social outcasts were believed to have special access to magic and the world of the dead. He often spoke of his desire to create a Tohoku Kabuki, reinstating the raw power of the bawdy beginnings of Kabuki while it was still a reactive art close to the folk and not yet cleaned-up for the West. White rice-powder painting of the face and body create ghostly appearances in butoh aesthetics as evolved in the work of Hijikata’s disciples, subliminal reminders of the ghosts of Kabuki and Noh Theater, even though we know that Hijikata distanced himself from traditional and classical theater, both East and West. White faces and bodies link to Japan’s traditional aesthetics, but in butoh these come paradoxically in the guise of darkness. Perhaps the best-known contemporary butoh company in this respect is the polished and popular Sankai Juku, grounded spiritually in the pre-history of the body, as conceived by choreographer Amagatsu Ushio.

Today’s butoh dancers are still plastered with mud or offset with chalky white, as they were in Hijikata’s day. The same bodies can also shine in glowing theatrical metamorphosis. Butoh can be plain and simple: still, slow, and stark. As Japan’s most prominent performance export, butoh is deconstructive in its own way: “The body that becomes” is the ontic, metamorphic signature of butoh aesthetics, recently sustaining new permutations like MoBu – blending modern dance with butoh stylizations. Butoh’s deconstructive tendencies can be wild in ways the West does not often associate with the East – free and uninhibited, nude and raw. Butoh can also be understated and smooth, cultivating small details of movement in facial expressions that move and melt sublimely (Ibid. 337). The refractive imagery of butoh does not idealize nature,

Figure 1.3 Ohno Kazuo in his modern dance days, before going to war. Courtesy Ohno Kazuo Archive

nor does it present human nature as such. Rather butoh dancers expose multiple natures as they become insects, or struggle to stand upright and pass through states of dissolution as in Hijikata’s famous “Ash Pillar” process. As pillars of ash, dancers enter the paradox of themselves, struggling for presence while disintegrating.

Contradicting the balanced essence of ballet, butoh plies the excitement of being off-balance, and the psychic path of shaking and plodding. Its somatic subtly goes to hair-splitting extremes. Takeuchi Mika and Morita Itto who base their butoh therapy in the movement work of Noguchi Michizo teach that what you experience depends upon how well you discern “hair-splitting” minute differences. Characterized by subtle change, butoh is not one thing: Morphing faces, states of limbo and contradiction, mark its beautiful ugliness. A dance film made in the 1960s by Hosoe Eikoh featuring Hijikata and his wife Motofuji Akiko, Heso to Genbaku (Navel and Atomic Bomb) is an early example of butoh metamorphosis or “the body that becomes,” also grasped in the irreconcilable poetics of Hijikata as “the nature that bleeds.” Morphing, melting figures permeate butoh. Their meaning is not literal but ongoing and open to interpretation.

Although Hijikata disavowed religion, the irrational non-doing of Zen, deeply embedded in the quietude of Japan, is subtext in much butoh. In his final workshop, Hijikata encouraged students to disperse into “nothingness” – quite a Buddhist ruse. Kasai Akira, who danced with Hijikata in the formative years of butoh, states that surrealism and the theater of the absurd influenced Hijikata early in his career (Fraleigh 1999: 232). Hijikata’s search for a Japanese identity resulted in surreal (or disorienting) aesthetic features of butoh techniques. The butoh aesthetic loops historically from Japan to the West, and goes back to Japan. More recently it reaches out internationally toward a “community body” of floating and gravitational powers in the work of Kasai (Ibid. 247–9), while the Jinen Butoh of Takenouchi Atsushi approaches the aura of death chambers and the far-reaching effects of nuclear fallout – dancing on the killing fields of war.

Butoh Alchemy in Global Circulation

As their butoh grew through the latter part of the twentieth century, Hijikata and Ohno rejected the theater dance of their time, whether modern or traditional – American, European, or Japanese. It is possible, nevertheless, to trace butoh’s influences back to the original expressionist “stew” of modern dance in the 1920s and 1930s, and to discern traditional Japanese aesthetics in butoh as well: from the theatrical flair of Kabuki and inscrutable slowness of Noh to the exaggerations of physique and stylized facial expressions in Ukiyo-e color prints. Butoh is based on individual experiment, the same faith in intuitively derived movement and improvisatory exploration that fueled the expressionist beginnings of modern dance. But butoh differs from earlier dance experiments through its inclusive return to Japanese folk roots, while at the same time exposing a postmodern jumble of cross-cultural currents, just as Tokyo itself meshes East and West in its post-war culture, and throughout Japan, one can find amazing aesthetic as...