This is a test

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Legacy of Boadicea explores the construction of personal and national identities in early modern England. It highlights the problems and anxieties of national identity in a nation with no native classical past.

Written in an accessible style, The Legacy of Boadicea:

* offers powerful new readings of the ancient British past in Shakespeare's King Lear and Cymbeline

* persuasively illuminates a 'Boadicean' heritage in royal iconography, drama, and the social symptoms of religious dissent

* articulates parallels between the eventual domestication of Britain's warrior queen in Restoration drama, and the social, political and legal decline in the status of women.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Legacy of Boadicea by Jodi Mikalachki in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From Mater Terra to the Artificial Man

At the beginning of modern moral and political philosophy stands a powerful metaphor: the “state of nature.” This metaphor is at times said to be fact.

Seyla Benhabib, Situating the Self

The founding text of the modern philosophical tradition described above is Hobbes’s Leviathan, composed during its author’s royalist exile in Paris in the late 1640s and first published in 1651. Hobbes’s (in)famous articulation of “the life of man” in the state of nature – “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short” – owes much to the English civil wars of the mid seventeenth century and the political chaos of national government before Cromwell established his republican sovereignty in the 1650s. In the new political “science” of the Leviathan, Hobbes developed a theoretical analysis of the crisis of national government in England (and other western European nations) in the seventeenth century. At the same time, in his founding metaphor of the state of nature as one of unmitigated savagery and conflict, Hobbes wrote into his theoretical apparatus the anxieties about native origins that had so exercised an earlier generation of nationalist English writers. The metaphor of the state of nature that stands at the beginning of modern moral and political philosophy is thus arguably derived from the historiographical “fact” of early modern English anxiety about native origins.

This chapter moves toward a sustained reading of the Leviathan’s two formative metaphors – the state of nature and the titular Leviathan or “Artificial Man” – as theoretical responses to the preceding century’s historiographical recovery of native origins in England. To frame this reading, I juxtapose Hobbes’s “Artificial Man” with an earlier figure I call “Mater Terra” – a composite of various feminine icons of the nation, ranging from portraits of Elizabeth I to topographical allegories and maps. Over the first half of the seventeenth century, the predominantly feminine iconography of Elizabeth’s reign was first effaced and then replaced by masculinist theory and imagery of the state. Foregrounding the category of gender, I survey the shift in national iconography from the feminine images of Elizabeth’s reign to the bearded king of Hobbes’s title page. Both recalling and supplanting the earlier images, Hobbes’s “Artificial Man” represents the early modern state as fully and exclusively masculine.

My literary and iconographical reading of the Leviathan complements reassessments of Hobbes and social contract theory by feminist political theorists. Just as women or feminine allegories disappear from national iconography during the first half of the seventeenth century, so women’s experience drops out of articulations of political theory. These parallel effacements of the feminine go beyond the conventional subordination of women to men. As Seyla Benhabib (whom I quote in the epigraph to this chapter) argues, “It is not the misogynist prejudices of early modern moral and political theory alone that lead to women’s exclusion. It is the very constitution of a sphere of discourse which bans the female from history to the realm of nature (1992: 157). In the “visual discourse” of national iconography, and in the overwhelming rhetorical bias of the Leviathan, both “the female” and “the realm of nature” lose their preeminence in English national iconography. My reading of the images, and my consideration of Hobbes’s metaphors, explore the trajectory and the means of this effacement; i.e., the cultural history of how the conventional femininity of national iconography was replaced by the masculinist imagery and rhetoric of the state in the Leviathan.

Other historicist accounts of Elizabethan nationalism have also taken the mid seventeenth century as their horizon. Arguing for the development of a non-dynastic vision of the nation in maps, topographical allegories, and even some royal portraits, these accounts draw a direct line from what they perceive as an iconographical struggle between crown and people to the civil wars of the mid seventeenth century. Both the reductive “crown/country” dichotomy and the historiographical determinism that inform these readings have undergone serious challenges and qualifications in the last two decades. In developing my own narrative of cultural change in this period, I emphasize the continuity of certain conflicts and anxieties inherent in the materials of English national recovery and self-representation. The trajectory I trace from Elizabethan nationalism to Hobbes is both political and cultural. It begins with a reassessment of Elizabeth’s “authorship” of the first English county atlas, develops into a critical reading of authority and gender in Hobbes’s political science, and concludes with the imaginary world of Margaret Cavendish, the first science fiction author.

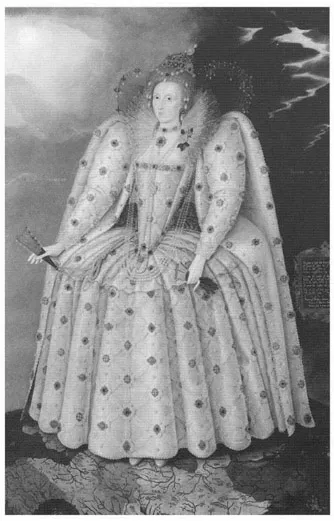

Two Monarchs’ Bodies

As has been frequently noted, Saxton’s county atlas bore neither title nor author’s name at its 1579 publication. Rather, it was introduced by an engraving of Elizabeth, crowned and enthroned, bearing scepter and orb, and flanked by figures of cosmography and geography (Figure 1). Her place on the title page of the county atlas has generally been taken as a sign of her authority over the administrative units represented within it. The most elaborate treatment of the title page, Richard Helgerson’s “The Land Speaks: Cartography, Chorography, and Subversion in Renaissance England,” extends this thesis to give Elizabeth ultimate “authorship” of the atlas, as head of the chain of patronage that hired Saxton and produced the maps. Helgerson compares the county atlas title page with the Ditchley portrait of Elizabeth by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, where the queen stands on a map modeled on Saxton’s composite of England and Wales (Figure 2). In company with most readers of the images, he takes both portraits as deliberate and insistent statements of royal power over the land represented. Helgerson regards the Ditchley portrait as a more fixed and unchallengeable version of that power. Noting the gradual exclusion of the royal arms from reprints of Saxton’s maps and later versions of the county atlas, he posits a progressive marginalization of royal and dynastic claims in favor of a land-based model of national identity. Helgerson locates the agency of this shift in what he calls the “built-in bias” of the map as a form of representation, where such surrounding symbols of royal control as arms and insignia are made to look marginal and merely decorative, as against the intrinsic features of the land itself (1992: 51–85).1

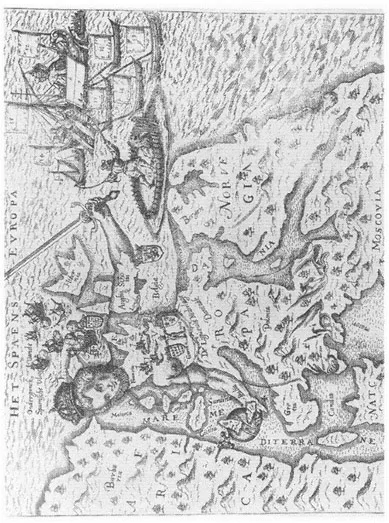

This large claim for cartography as the originator and primary agent of national transformation has a number of problems. First, it is by no means clear, as Helgerson claims, that “there is really no way to overcome” the built-in cartographical bias as he defines it. The royal presence need not be relegated to the margins of a map, as indeed it is not in a 1598 Dutch engraving of Europe as Elizabeth I, where the queen’s left arm forms England and Scotland, her right, Italy, and her body, the mass of the continent (Figure 3). Neither need one designate the framing material of an image as less “intrinsic” than what it contains and to some measure defines. Still less should that image be taken in isolation as the origin and cause of the kind of massive shift in national identity Helgerson ascribes to it. In his confessedly Whiggish reading of chorographic developments, Helgerson sees cartographic representation as having increased both local and national identity at the expense of dynastic loyalty. “Maps thus opened a conceptual gap between the land and its ruler,” he concludes, “a gap that would eventually span battlefields” (114).

![1. Frontispiece to Christopher Saxton’s [Adas of England and Wales] (1579) (C.3.bb.5), by permission of the British Library.](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1617055/images/fig1-plgo-compressed.webp)

1. Frontispiece to Christopher Saxton’s [Adas of England and Wales] (1579) (C.3.bb.5), by permission of the British Library.

2. “Ditchley” portrait of Elizabeth I, attr. Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (1592?), courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

3. Map of Elizabeth I as Europa (1598), by permission of the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology.

The Whig model of an inexorable movement toward the civil wars of the mid seventeenth century has been largely discredited by social and administrative historians of early modern England.2 Even if one were to accept it provisionally, Helgerson’s location of the agency of this drive in a claimed imperative of cartographical representation would still need qualification. In his claim that maps “opened a conceptual gap between the land and its ruler,” Helgerson assumes a split between the land and the monarch, in which these two embodiments of the nation are engaged in a struggle for mastery over its representation. His premise is that once the land is stripped of encroaching royal symbols and presented in its “naked” state, then the rival figure of the monarch will be banished as the constitutive body of the nation. And yet, if one takes seriously the identification of Elizabeth’s body with the land, an identification that is a necessary prelude to Helgerson’s imagined gap, the figure of the queen can be taken as present in any representation of the land.3

Helgerson remarks of the Ditchley portrait in passing, “After all, by putting the queen on the map the Ditchley artist had hidden what most people bought an atlas to see – a representation of the land itself” (112). And yet the land “itself” as represented by the Ditchley artist seems to be precisely a version of the queen’s body, the flat representation of what she in her three-dimensional majesty embodies: the nation. One might read the county atlas title page in the same way; the image of the monarch, herself the embodiment of the nation, introduces the maps that will follow. The cartouche beneath her feet bears the Latin inscription “Clemens et Regni moderatrix iusta Britanni / Hac forma insigni conspicienda nitet,” a crude English rendering of which would be “The merciful and just ruler of the Kingdom of Britain / Shines in this notable image, worthy of being seen.” “Hac forma” this figure, shape or image, presumably refers to the frontispiece – i.e., the figure of the queen – and yet its representational insistence on likeness and outline might apply as easily to the maps, equally notable and worthy of being seen. This conflation of the figure of the queen and the figures of the maps suggests not so much an imposition of royal authority on the otherwise neutral or subversive map, but rather a construction of mutual identity out of the interplay of the queen’s body and the land.

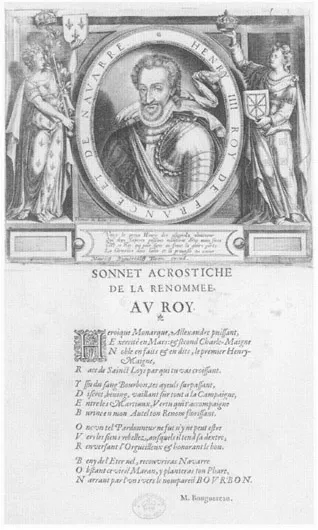

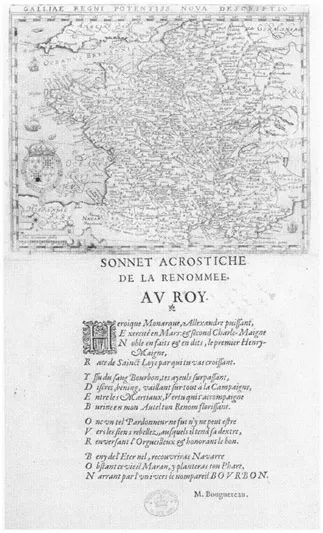

The importance of this interplay, and its distinctiveness to Elizabeth, emerges more fully through comparison to a contemporary topographical work dedicated to another monarch and representing another kingdom. Maurice Bouguereau’s Le Théâtre François, où sont comprises les chartes générales et particulières de la France, was prepared and presented to Henri IV in 1594 to commemorate the king’s retaking of Paris after the revolt of 1589–94. It is the first atlas of France, and was explicitly designed as a symbol of national unity under one monarch.4 The atlas opens with a description of its contents, an advertisement for subscribers, and a chronology of the kings of France from the legendary Pharamond to Henri IV. The second leaf presents the standard topographical title page, with the full title framed by a classical arch. On its verso is a halfpage portrait bust of Henri IV in armor, flanked by female personifications of France and Navarre (Figure 4a). French verses in a cartouche praise Henri for his military victories and his clemency. On the lower half of the page is an acrostic sonnet to Henry Bourbon by Bouguereau (7l2v).

In many ways, this page recalls the title page of Saxton’s atlas. Both monarchs are framed by personifications and celebrated in verses on their glory and clemency. Each seems to stand as an emblem or embodiment of the nation represented cartographically in the atlas. The emblems differ slightly in that Elizabeth’s whole body performs this function, whereas Henri’s head and torso alone appear. They are also placed differently. Elizabeth’s portrait is the first page of Saxton’s atlas, and her name appears nowhere on it, as though her forma alone introduces and authorizes the atlas. In contrast, Henri’s portrait appears on the verso of Bouguereau’s second leaf, after the title page and other written preliminaries. The king’s image is almost obsessively supplemented by the written characters of his name, in the frame surrounding the portrait, the verses in the cartouche, and the acrostic sonnet to Henry de Bourbon. One last feature of Henri’s portrait reveals the most important difference between the representational properties of these two royal bodies.

The half-page portrait of Henri IV is in fact an addition to the printed title page of Bouguereau’s atlas. Glued along its top edge only, it folds up to reveal a map of France beneath, printed above the acrostic sonnet in the space covered by the portrait (Figure 4b).5 Unlike Elizabeth, then, Henri does not introduce the maps of his kingdom in an exclusive and unified embodiment of the nation. Rather, on the verso of the second leaf, his figure and his name stand interchangeably with another figure, “GALLIAE REGNI POTENTISS. NOVA DESCRIPTION The icon of king-as-nation thus emerges mechanically from the manipulation of the half-page addition to the title page, a device that precludes viewing both images simultaneously. By contrast, the single icon of the queen-as-nation that introduces Saxton’s atlas stands in place of any competing image or title for the collection of maps that follows.

I suggest that the Saxton title page functions so fully as an emblem for the whole atlas because the monarch it represents is female.6 The land-based constructions of the nation that emerged and flourished in sixteenth-century England inevitably and centrally involved gender.7 Their

4a. Portrait of Henri IV in Maurice Bouguereau, Le Théâtre François (1594) (C.7.C.22), by permission of the British Library.

4b. Map of France in Maurice Bouguereau, Le Théâtre François (1594) (C.7.C.22), by permission of the British Library.

scholarly and aesthetic issues of gendered representation participated in a broader transformation of cultural and political representation. The mutually constitutive bodies of Elizabeth and the land produced a powerful feminine icon of the nation that was not easily supplanted in the succeeding reigns of James and Charles. The struggle to efface this feminine icon and replace it with a masculine image of the state lasted for almost fifty years after Elizabeth’s death. Its early years coincided with the peak of topographical nationalism in the 1610s. Despite James’s accession and insistently patriarchal style, the composite icon I call “Mater Terra” dominated the major n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- List of Plates

- Acknowledgements

- Note on citations

- Introduction

- 1 From Mater Terra to the Artificial Man

- 2 King Lear and the tragedy of native origins

- 3 Cymbeline and the masculine romance of Roman Britain

- 4 The domestication of the savage queen

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index