- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Conversant in contemporary theory and architectural history, Stan Allen argues that concepts in architecture are not imported from other disciplines, but emerge through the materials and procedures of architectural practice itself. Drawing on his own experience as a working architect, he examines the ways in which the tools available to the architect affect the design and production of buildings.

This second edition includes revised essays together with previously unpublished work. Allen's seminal piece on Field Conditions is included in this reworked, revised and redesigned volume. A compelling read for student and practitioner alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Drawings

- I Constructing with Lines: On ProjectionPostscript: Review of Robin Evans: The Projective Cast

- II Notations and Diagrams: Mapping the Intangible:

- III Terminal Velocities: The Computer in the Design Studio Postscript: The Digital Complex

I Constructing with Lines

On Projection

DOI: 10.4324/9780203723708-2

It is quite possible to project whole forms in the mind without recourse to the material, by designating and determining a fixed orientation and conjunction for the various lines and angles.L. B. Alberti

Hunting the Shadow

Architecture is often defined as the art—or science—of building. Yet architects, when they build, influence construction only indirectly, at a distance. As Robin Evans has succinctly put it, “architects do not make buildings, they make drawings for buildings.” In Alberti's treatise, a privileged place is assigned to the abstract, intellectual work of Lineaments—linear constructs projected “in the mind,” as opposed to material constructions in the world.1 But to see the working constructions of the architect—drawings, models, notations, or projections—as simply opposed to the concrete physical reality of building is to miss what is specific to architectural representation. Projection, in particular, implies movement, transformation. By the translation of measure and proportion across scale, architectural projections work to effect transformations of reality at a distance from the author. Projections are the architect's means to negotiate the gap between idea and material: a series of techniques through which the architect manages to transform reality by necessarily indirect means.2

Many discussions of drawing begin with the classical legend of the origin of drawing.3 As narrated by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, the story is marked by themes of absence and desire. Diboutades, daughter of a Corinthian potter, traces with charcoal the outline of the shadow cast by the head of her departing lover. Projection is fundamental to the story. Diboutades traces not from the body of her lover but from his shadow—a flat projection cast on the surface of the wall by the soon-to-be absent body. At the moment of tracing, Diboutades turns away from her lover and toward his shadow. Information is always lost in projection: the fullness and physicality of the body is converted into a two-dimensional linear abstraction. The drawing stands in for the absence of the lover: an incomplete image to recall a lost presence.

The legend of Diboutades stages a relationship between a body and its representation, mediated by flatness and projection. The drawing records in abstracted form something that already exists but will soon be absent. It will act as a token to recall the memory of the lover when he is no longer present. The legend enacts classical theories of mimesis—art imitates nature, and the presence of the subject precedes the artifice of representation. In classical thought, the representation can be more or less accurate, but it will always be secondary, a shadowy simulation of a preexisting reality.

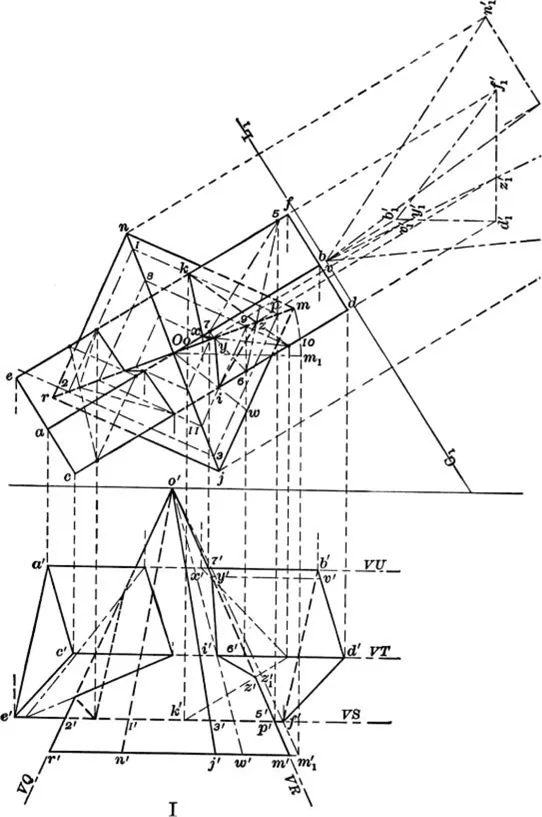

The function of representation in architecture is related but distinct. In “Translations from Drawing to Building,”4 Robin Evans contrasts the typical product of the academic painter to a version of the Diboutades story painted by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Two significant differences emerge. In the version from the academic tradition, the light is from a candle and the scene takes place in an intimate interior setting. Schinkel's version is set out-of-doors, and the rays of the sun provide the source of light. The sun's rays, for practical purposes considered parallel, produce an orthographic projection, while the radiating vectors of the candlelight effect a type of projection more closely related to single point perspective. Hence, the architect's version employs the abstract projection of the mechanical draftsman—measurable and precise, capable of transmitting information—while the painter's version employs a more pictorial projection, producing an iconographic image.

Second — and more significant — is the scene of the drawing itself. In Schinkel's painting, the tracing is executed by a young shepherd, under the command of a woman who directs the act of drawing while steadying the head of the model. The painting depicts not an intimate interior setting, sheltered by an already fully formed architecture, but a pastoral scene, and a complex social exchange. Instead of a dressed plaster wall, the shadow is traced out on the more or less even surface of a stone ledge in the landscape. As Evans points out, for Schinkel, the neoclassical architect, drawing necessarily precedes building and its subsequent codification of the norms of social behavior and civilization. Without drawing there is no architecture, or at least no architecture as Schinkel would have understood it: a classical architecture of regulated proportions and integrated formal orders. Drawing is identified with abstract speculation and geometry, and in turn, with social formation. Despite his portrayal of drawing as a more complex social scene, Schinkel has depicted the act of tracing at exactly the moment when the stylus rests on the shadow of the eye, as if to indicate the primacy of vision.

Schinkel's painting suggests that classical theories of imitation fall short of explaining the workings of architectural drawing. In architecture there is no preexisting object to imitate: no body to cast a shadow.5 Once established and codified, architecture tends to imitate preexisting architectures; but what does it originally imitate? Or, as Mario Carpo has put it, “How do you imitate a building that you have never seen?” 6 Alberti, for example, states that architecture imitates nature by subscribing to the same set of abstract, cosmological ordering principles. Architecture imitates nature through harmony, number and proportion. In enlightenment architectural theory, the figure of the primitive hut is introduced; architecture imitates nature by finding its origins in the most basic and “natural” of architectural forms. But if classical architecture imitates nature in the form of the primitive hut, it does so only through a highly abstract and idealized geometrical mediation. Even later attempts to link architecture more closely to a mimetic idea of nature—Viollet-le-Duc's idea that the logics of structure imitate organic structure, or Gottfried Semper's idea of the wall as a woven mat—do so through conventionalized (and abstract) means. Multiple layers of convention, history, geometry, and form-making intervene to make these stories of origin unconvincing.

As in the legend of Diboutades, architectural drawing is marked by the sign of absence. But unlike classical theories of imitation, the represented object does not exist prior to its depiction in drawing: not something that once was and is no longer present, but something not yet present. Buildings are both imagined and constructed from accumulated partial representations. The drawing as object, like the musical score in performance, disappears at the moment of construction. But how is this transformation accomplished? Projection translates measure, interval and profile from two to three dimensions, across scale. Difference, as much as correspondence, configures the translations between drawing and building. Drawing heavily on Robin Evans’ insights on the functioning of projection, this essay surveys specific practices of projection—perspective, anamorphosis and axonometric—in their historical and theoretical context. My interest throughout is in the interplay between the abstract constructions of drawing and architecture's specific capacity to transform reality.

To examine techniques of representation in this way is neither to suggest that architecture could ever be exclusively concerned with geometry and representation, nor to subscribe to the view that the problem of drawing is to get past its abstract character in favor of a more direct contact with the physical fabric of architecture. The capacities and logics of drawings are necessarily distinct from the potentials of construction. “Projection operates in the intervals between things. It is always transitive.” 7 Following Evans, my method is to pay close attention to the transactions between the culture of drawing and discipline of building. The conclusion I draw from this analysis is that, difficult as it may be, the architect must simultaneously inhabit both worlds. Instead of reiterating fixed categories, what seems important today is to recognize the interplay of thought and reality, imagination and realization, theory and practice.

In his treatise on architecture Vitruvius had long ago pointed out that “architects who have aimed at acquiring manual skill without scholarship have never been able to reach a position of authority to correspond to their pains, while those who relied upon theories and scholarship were obviously hunting the shadow, not the substance.”8 Architecture proposes a transformation of reality carried out by abstract means. But the means of representation are never neutral, never without their own shadows.9 In the case of architecture, it is the ephemeral shadow of geometry cast on the obstinate ground of reality that marks the work of architecture as such.

A dream is, among other things, a projection: an externalization of an internal process.Sigmund Freud

Vision and Perspective

In order for classical architecture to identify itself with the exact sciences, architecture had to establish its foundations in mathematical reasoning. Architecture could be scientific only to the extent that it was mathematical.10 In classical theory, perspective offered a geometrical means to order the constructed world in accordance with nature. Perspective linked the perception of the world to ideas about the world through the vehicle of mathematical reason. But perspective also functioned as a concept of time: ordering, surveying and recreating the past from the privileged viewpoint of the present. Just as the distant Roman past was rediscovered/reinvented on the basis of ruins and fragments, so the viewing subject could reconstruct the narrative space of painting by means of perspectival projection. Space is read in depth—locating the spectator in front of and in the present, from which the distance/past is entered and traversed. Perspective establishes a spatial field that supports narrative time.11

The mathematical calibration of the visual world allowed other correspondences. The analogies between musical and proportional harmonics were established on the basis of their common foundation in geometry. Cosmological, religious, and philosophical consonances were played out on the basis of the geometry of space and its relation to an idealized body. Even emerging sciences of ballistics and fortifications could be given a metaphysical overtone by contact with geometry. Seeing was understood as a natural function of the eye; the paradigms of Renaissance painting naturalized an idealized concept of vision. As Erwin Panofsky has pointed out, perception and concept were unified in Renaissance perspective practices: “‘esthetic space’ and ‘theoretical space’ recast perceptual space in the guise of one and the same sensation: in the one case that sensation is visually symbolized, in the other it appears in logical form.” 12 In architecture, the smooth space of mathematical reason allowed the architect to reverse perspective's narrative vector and project precisely imagined constructions into the future.

The constructions of perspectival geometry then, appear to enforce the privilege of the perceiving spectator. But Norman Bryson, elaborating on the speculations of Jacques Lacan concerning optics, has pointed out that the presence of the viewing subject implies a corresponding absence: “The moment the viewer appears and takes up position at the viewpoint, he or she comes face to face with another term that is the negative counterpart to the viewing position: the vanishing point … The viewpoint and the vanishing point are inseparable.”13 If, as Renaissance theory wants to suggest, the proper perspectival construction contains within it an ideal viewing distance, which fixes the position of the spectator, the spectator is at this moment also effaced. The viewer, in facing the vanishing point, is confronted with a “… Black hole of otherness placed at the horizon in a decentering that destroys the subject's unitary self possession.” 14 The very possibility of the subject's being in the picture is inextricably linked to its displacement from the picture.

In Albrecht Dürer's 1525 woodcut “Artist Drawing a Lute” the paradox of the viewing point, and its decentering effect, is underlined. Laid out perpendicular to the viewer's line of sight, a lute sits on a table to which a wooden frame has been attached. A hinged panel holds the drawing that is being produced. It has been rotated ninety degrees from the frame, which turns it toward the viewer, who can observe a series of points forming the outline o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- INTRODUCTION

- DRAWINGS

- BUILDINGS

- CITIES

- Image Credits

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Practice by Stan Allen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.