This is a test

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

European and Native American Warfare 1675-1815

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Challenging the historical tradition that has denigrated Indians as 'savages' and celebrated the triumph of European 'civilization', Armstrong Starkey presents military history as only one dimension of a more fundamental conflict of cultures, and re-examines the European invasion of North America in the 17 th and 18 th centuries. Combining the perspectives of ethno-history and military history, this book provides an evaluation of the evolution and influence of both Indian and European ways of war during the period. Significant conflicts are analysed including King Philip's war in New England (1675-1676) notable due to the number of armed Indians, the American War of Independence, and the conquest of the old Northwest, 1783-1815.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access European and Native American Warfare 1675-1815 by Armstrong Starkey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter One

Introduction: raiders in the wilderness

Fort Bull

On 27 March 1756, a starving and exhausted raiding party of French, Canadians and American Indians emerged from the forest near Fort Bull, a fortified Anglo-American storage depot located at the great portage on the way from Schenectady, New York to Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario. The detachment of 362 men under the command of Lieutenant Chaussegros de Léry had made an arduous 15-day march from Lachine struggling through heavy snow, ice and torrential rains. Despite the deer shot by their Indian hunters, the men had been without food for two days.1

Now they found themselves astride a much travelled military supply road linking Wood Creek with the Mohawk River. At 10.00 am Léry’s Indian scouts captured two sleighs loaded with provisions and the party broke its involuntary fast. Learning that a servant accompanying the sleighs had escaped to give the alarm at neighbouring Fort Williams at the far end of the portage, Léry determined to attack Fort Bull immediately. The Indians in his force protested this decision. They argued that they were fortunate to have captured sufficient food to see them home and that it would be tempting fate to try more. “If he desired absolutely to perish”, they said, “he was master of his Frenchmen.”

Léry was an experienced frontier commander. Born in Canada, the son of a French military engineer, he had been commissioned as an officer in the troupes de marine, French regulars stationed in the colonies and commanded by colonial officers. Although following in his father’s footsteps by qualifying as an engineer, he had cut his teeth in frontier warfare during raids on the New England frontier in 1746–8. Now he demonstrated his ability to lead Indian warriors. Recognizing that Indians seldom risked an assault on a fortified position, he replied that he did not wish to expose them, but asked for only two volunteers to serve as guides. Eventually, some 20 of the 103 Indians, aroused by drams of brandy, agreed to join in the assault. The remainder posted themselves in ambush along the road from Fort Williams.

Léry hoped to surprise Fort Bull without firing a shot. His French and Canadian troops, a mix of regulars (troupes de terre recently despatched from France), colony regulars and Canadian militia, fixed bayonets and advanced quickly upon the fort. But the Indians, on flushing a small English work party, emitted a war whoop which alerted the garrison, who managed to bar the gate. Fort Bull was not a proper fort in the eighteenth-century European style. Rather it was a stockaded supply depot and the garrison of 60 men was armed only with muskets and grenades. When the French- Canadians gained possession of the loopholes in the fence, they were able to fire into the fort and the enclosed area became a killing ground. Under the cover of this ferocious fire, the gate was soon battered in. One account of the engagement indicates that Léry summoned the English commander to surrender, promising quarter to the garrison, but was answered by a volley of musketry. Such an offer and refusal could be used to justify the subsequent event. Breaking into Fort Bull during a bitter struggle of almost an hour, the French-Canadians bayoneted nearly the entire garrison. No more than three or four prisoners were taken.

On hearing the sounds of battle, the British garrison at Fort Williams despatched a relief force. They promptly fell into an ambush by the Indians posted on the road. Seventeen of the Fort Williams party were killed before they could regain the protection of their stockade. One of the Indian chiefs asked Léry if he now proposed to attack the other fort. He replied that “he would do so forthwith if the Indians would follow him. This reply drove this Chief off, and all his party prepared to go after him.”

Léry himself may have had no intention of attacking Fort Williams, which he knew to be provided with cannon and more strongly built than Fort Bull. The latter had caught fire during the battle and the powder magazine exploded, destroying all of the supplies accumulated within the depot. Aware that large Anglo-American reinforcements would soon appear, he led his men back into the forest for the trek to Lake Ontario. Again food ran short. The raiders subsisted in part upon horse flesh and “had even devoured a porcupine without any other dressing than sufficed just to scorch off the hair and quills”. All depended upon meeting supply boats at the appointed rendezvous. After a march of seven days, they arrived only to find the bay empty. This cast the raiders into despair as once again they faced the prospect of starvation. They kept a cold and hungry watch until M. de la Saussaye arrived with the rescue bateaux on 13 April, 17 days after the attack on Fort Bull.

Léry had executed a remarkable winter raid with the loss of only three dead and seven wounded. He had exposed the fragility of Fort Oswego’s supply line and dealt a severe blow to Anglo-American preparations for a summer offensive on Lake Ontario. Aside from the material damage, this successful deep strike into British territory sapped Anglo-American morale. Indeed, it may be said to have been the opening move in the Marquis de Montcalm’s capture of Fort Oswego in August 1756, a victory which strengthened the French grip upon the Ohio country.

Aside from its strategic significance, this little campaign offers insight into the issues of this book: European versus North American Indian styles of warfare. As should be evident from the preceding account, the two styles were not necessarily incompatible. Léry’s force included a large party of allied Iroquois, Algonquin and Nepissing Indians who played an indispensable role as scouts, hunters and skirmishers. The French-Canadian raiders, striking out into the forest in the midst of winter without an assured source of food, had adapted themselves to an Indian way of war which demanded tremendous physical endurance and indifference to deprivation. Still, it is unlikely that they would have risked such a march without Indian support. Once the battle for Fort Bull erupted, the two styles of war parted: the Europeans fixed bayonets and assaulted a fortified position while the majority of the Indians withdrew into the woods to prepare an ambush. The latter reminded Léry that he was master of the French, but not of them. They considered themselves allies rather than subordinates bound to follow orders not to their liking. He was intelligent enough not to force the issue, but rather found a way by which they could render useful service. The outcome of the assault upon the fort was a “massacre”. Indeed, more people were slain at Fort Bull than during the celebrated “massacre” at Fort William Henry in 1757. But the slaughter at Fort Bull was carried out by French-Canadian troops who gave no quarter to the hapless garrison once they stormed the gate. If it is true that Fort Bull’s commander had rejected Léry’s summons, the killing of the defenders was consistent with European military custom and the laws of war. This should be kept in mind when one considers the “barbaric” martial customs of eighteenth-century North American forest Indians.

Léry’s achievement may be contrasted with that of his contemporary, Major Robert Rogers, whose rangers were the most famous Anglo-American frontier fighters of the time. Although he was a bitter enemy of the French- Canadians and their Indian allies, he admired the martial culture and warlike methods of the Indians and adapted them to his own use. Like most successful frontier commanders, he included companies of Indians among his troops. While his battle success was mixed, his rangers were the invaluable eyes of the Anglo-American army in the Lake George-Lake Champlain region during the Seven Years War. In September 1759, Rogers led a force of rangers against the Catholic Abenaki Indian settlement at St Francis near Montreal. During the march overland from Lake Champlain, nearly a quarter of his force became disabled and had to be sent home. He successfully attacked the Indian settlement, burning the dwellings and killing or capturing a number of the inhabitants. Rogers claimed to have killed 200 Indians and to have captured 20, but some authorities accept the French figure of 30 dead. It is unclear how many Indian warriors were present at the time of the raid, but large numbers swiftly assembled in pursuit of the rangers whose retreat became a nightmare. They were reduced to eating roots and cannibalizing the corpses of comrades when supply boats failed to appear at their rendezvous on time. Rogers lost almost half of his command of 200 on this expedition.

Rogers proved that he could penetrate Canada and destroy the Abenakis’ sanctuary. The Abenakis’ sense of security was badly shaken by the raid, but it is not always clear who “won” engagements of this sort. Lieutenant Colonel John Armstrong’s raid on the Delaware village at Kittanning on the Allegheny River on 8 September 1756 was celebrated as an Anglo-American victory at the time. Armstrong caught an unfortified village by surprise, killed a prominent Indian military leader, and rescued a few prisoners. After the attack, the Indians abandoned Kittanning and withdrew across the Ohio. Indian morale seems to have suffered from this blow, which in turn lifted sagging Anglo-American spirits. On the other hand, although Armstrong enjoyed the advantage of surprise and a numerical advantage of three to one, casualties were roughly equal on either side and the bulk of the prisoners remained in Indian hands. Armstrong’s raid failed to end the Indian threat to Pennsylvania’s white frontier settlements. Armstrong had achieved qualified success, but the Indian combatants, whose primary concern was to avoid loss of life, could also claim victory. As we will see, Europeans and Indians often defined victory by different standards.,2

European “invasions” of America

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the period covered by this study, Indians in eastern North America conducted a protracted and often successful military resistance against what many historians now perceive to have been a series of European invasions of North America.3 Armed resistance against English settlement began in Virginia in 1607 and ended in the “Old Northwest” only after the defeat of an allied British-Indian confederate army by United States General William Henry Harrison at the battle of the Thames Fallen Timbers in 1813. During this time, Europeans fought Europeans for the control of an American “empire”. Britons, French, Spaniards, Canadians, and Americans became involved in conflicts which increasingly resembled the conventional war practised in Europe. Indians fought on all sides of these conflicts for reasons of their own and played varying roles of central and marginal importance. However, when Europeans confronted Indians, it was usually within the context of frontier warfare, a kind of war in which the Indians were accomplished masters and in which the Europeans were frequently at a disadvantage. European officers found that if they were to be successful against Indian adversaries, it was best to have Indian allies. In retrospect, given the apparent European superiority in numbers, material and technology, it may seem surprising that Indian resistance lasted as long as it did. Europeans soon found that their apparent advantages did not guarantee success. They had a lot to learn about the ability of stateless native people to resist the advance of the most powerful, expansionist European empires.

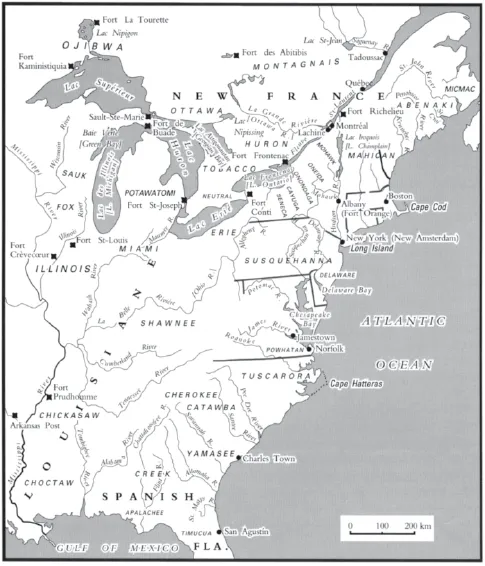

1. Seventeenth-century eastern North America

Most successful in dealing with the Indians diplomatically and militarily were those who made an effort to understand them. But Europeans often avoided such an effort when they relegated the Indians to the status of “savages”, a people without government, laws, social mores and cultural values. European conquest could thus be justified as a triumph of civilization over barbarism. Not surprisingly, Europeans tried to comprehend the Indians within a European context. New England Protestants’ understanding of their Indian neighbours was inevitably influenced by the religious struggles of the seventeenth century. A “godless” people outside the law of European society was automatically suspect. Still worse from the point of view of these Protestants were those Indians who came under the influence of Jesuit missionaries. Their satanic nature was thus confirmed. This perspective was central to the development of Protestant Anglo-American historiography, which celebrated English conquest and settlement as the inevitable and benign march of progress. This tradition reached its apogee in the nineteenth century in the works of Francis Parkman and held sway among professional historians at least through the first half of the twentieth.4 Indeed, despite the best efforts of revisionists, Parkman will probably influence the American popular historical tradition for some time to come.

Canadian writers have found Parkman’s perspective rather less satisfactory. But they too have often defined the Indians from the standpoint of their own culture without dealing with the Indians on their own terms.5Historians of both societies have often written to advance their own agendas. Much of the history written by the heirs of a European conquest inevitably celebrates it and justifies it. The North American Indians, losers and lacking academic historians of their own, were denied a voice.

Recent scholarship on these issues has occurred within a changed context. Developments such as multiculturalism, the struggle for minority rights, the Native American movement, and the end of the era of European imperialism have challenged the old elites in North American society and the historical tradition that supports them. New scholarly methodologies applying anthropological techniques to historical studies have advanced understanding of and appreciation for the non-literate cultures of the past. Indian peoples have thus emerged as three-dimensional people to be understood within their own context and upon their own terms, free from the traditional stereotypes of noble or ignoble savage, images refracted through the lenses of European culture. Although the new context is hardly free from bias (the challenge to the old elites being central to the current “culture wars” in North America), the nature of the Indian resistance to the European conquest of North America is the subject of more informed and sympathetic investigation.6

This is a story that goes far beyond military history. Military conflict was only one aspect of a clash of cultures and the adaptation of one culture to another. Military institutions do not exist in a vacuum; European—Indian military conflict was but one element in a complex set of contacts and exchanges between the peoples of North America. Indeed, war may have been the least important vehicle of European conquest. Epidemic diseases killed far more native people than did muskets or cannon and undermined the resistance of many tribes. Estimates of the North American Indian population in 1492 range from 1 to 12 million. Most scholars despairing at incomplete demographic data seem to split the difference between the two figures. The prevailing view is that waves of European epidemic diseases devastated Indian communities to the extent that European soldiers engaged in something of a mopping-up action. Although the relationship between disease, the cataclysmic collapse of Indian population levels and European conquest has recently been questioned, individual cases seem to bear it out.7 For example, estimates of the New England Indian population before European colonization range from 72,000 to 126,000–144,000. By 1670, on the eve of King Philip’s War, according to one estimate that number had been reduced to 8,600. Europeans suffered from disease too, but by 1670 their number was over 50,000.8 The populations of both the Hurons of modern Ontario and the Iroquois of northern New York were cut in half by epidemic diseases by 1640. Among the Great Lakes Indians in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries there were population declines ranging from 25 to 90 per cent. A visitor to the Carolina Piedmont at the beginning of the eighteenth century found the remains of whole towns destroyed by smallpox. It was simply the most recent in a wave of epidemics which had beset the region from the earliest contacts with the Spanish in the sixteenth century.9 As will become evident, population disparities contributed to European-Indian conflict and to the ultimate success of white conquest.

Disease paved the way for non-military agents of conquest. The arrival of Jesuit missionaries in the Huron country in 1634 coincided with the outbreak of a series of epidemics that reduced the population by half in six years. Jesuit immunities appeared to demonstrate the power of their religious message when Indian rituals and medical practices proved helpless in the face of disease. Jesuit missionaries successfully capitalized on a people weakened and demoralized by these disasters. Puritan missionaries in New England found the majority of their converts among those Indians most stricken by epidemics. The Massachuset tribe, reduced from 24,000 to 750 by 1631, provided many “praying Indians”, while the Narragansetts, unaffected by the epidemics, remained resistant to the appeal of Christianity and even experienced a revival of native religious belief.10 Both Protestant and Catholic missionaries conducted campaigns to alter Indian cultural life to conform with European practices. The Jesuits were willing to go farther afield than their Protestant rivals and were more skilful in adapting their message to the native cultural context, but as one scholar has observed:

The Jesuits’ reputation for tolerance and willingness to adapt Christianity to the traditions of their converts is deserved, but only in comparison with other seventeenth century missionaries. At bottom, they and other Catholic priests followed in less extreme form the doctrine that English ministers called “civility before sanctity”: only when Indians shed their native ways and adopted European customs could they truly become Christians.11

While missionaries transformed the lives of some Indian peoples, they created deep divisions in communities which were riven between converts and traditionalists. Consensus decision-making processes were undermined, elders lost influence, and the community lost the ability to respond to crises with unity. Factions among the Hurons in the wake of Jesuit missionary success sapped their ability to meet the Iroquois onslaught of the 1640s which destroyed their independence as a people.12 For a variety of reasons French missionary activity among the Iroquois after 1667 was less successful in registering permanent gains, but their influence also resulted in divided communities. Conflicts between non- Christians and Christians in the late 1660s and the 1670s resulted in a large emigration of the latter to settle in the mission community of Caughnawaga in the St Lawrence River Valley.13 Catholic Iroquois would prove valuable allies of the French in decades to come.

Jesuit missionaries possessed greater leverage with the Hurons than the Iroquois because they controlled the former’s access to European trade goods and firearms. The Iroquois had alternative sources. During the seventeenth century, the eastern Indians of North America had become part of the worldwide economic system, a fact that transformed native economies, introduced material conveniences such as metal tools and woolen blankets, and rendered the Indians dependent upon European commercial policies and market forces. Indian rivalries and Indian—European relations became governed by the European demand for furs. One scholar argues that the fur trade was by its nature an unequal exchange which extracted wealth from the margins, the North American forests, to the benefit of the European centre.14 This may have been true in macroeconomic terms, but clearly many Indians saw profit in the trade. While unscrupulous white traders sometimes used alcohol to take advantage of their Indian partners, other Indian traders showed that they had a shrewd idea of the value of their wares. Furthermore, the extent to which the trade disrupted the traditional Indian way of life seems to have varied. The leading expert on the Algonquian peoples of the Great Lakes Region finds that by the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the trade had caused little disruption of the native subsistence system. European items had more symbolic than material significance and the trade itself was conducted by the French more from diplomatic than commercial motives.15 However, Indian economies which were deeply integrated into the fur trade were vulnerable to market changes. Demand for beaver pelts collapsed after 1660, causing a decline in the value of wampum, a fur-backed shell currency. As will be demonstrated in ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of maps

- Preface

- Chapter One: Introduction: raiders in the wilderness

- Chapter Two: The Indian way of war

- Chapter Three: The European background to North American warfare

- Chapter Four: Total war in New England: King Philip’s War, 1675–6 and its aftermath

- Chapter Five: Indians and the wars for empire, 1689–1763

- Chapter Six: Wars of independence: the revolutionary frontier, 1774–83

- Chapter Seven: Last stands: the defeat of Indian resistance in the Old Northwest, 1783–1815

- Chapter Eight: Conclusion

- Notes

- Select Bibliography