eBook - ePub

The Saga of Sydney Opera House

The Dramatic Story of the Design and Construction of the Icon of Modern Australia

This is a test

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Saga of Sydney Opera House

The Dramatic Story of the Design and Construction of the Icon of Modern Australia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Peter Murray's compelling and highly readable biography of the building presents both sides of the story. Using previously unpublished files and papers, Murray has managed to unravel one of the most intriguing architectural controversies of recent times - what really happened when they built Sydney Opera House...

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Saga of Sydney Opera House by Peter Murray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A MAGNIFICENT DOODLE

In 1957, it took three days to fly from London Heathrow to Sydney and cost £430 and 4 shillings sterling. The journey included refuelling stops in Zurich, Istanbul, Karachi, Calcutta, Singapore, Jakarta and Darwin. Communication by telephone was expensive, connections had to be booked in advance and the quality of line was variable. Urgent communication was generally by telex or telegram. Today we inhabit a world of instant communications, of faxes, mobile phones, e-mails and the internet: it is hard to recall the meaning of distance in the days before the jet plane took over the skies. An appreciation of just how far away Sydney seemed from Europe in the 1950s is important in understanding the difficulties that beset the design and construction of the Opera House. The complications of cultural differences, of communications, of professional procedures and the fact that the long-distance traveller was virtually incommunicado all played their part in the unfolding drama.

It was clearly unrealistic for many of the overseas entrants to the Opera House competition to visit the proposed site and the first time Jørn Utzon saw the New South Wales capital and Bennelong Point, the striking promontory selected for the building, was in July 1957, six months after it was announced that he had won the competition for the new building. Utzon had studied the qualities of the promontory from photographs and postcards. It is a mark of his genius that he so brilliantly interpreted the location, the light and the landscape with his sculptural forms.

On first seeing Bennelong Point, he exclaimed to a Sydney Morning Herald reporter, ‘It’s absolutely breathtaking. There’s no opera site in the world to compare with it…this site is even more beautiful than in the photographs from which I worked.’

The selection of Bennelong Point for the future Sydney Opera House had been pinpointed in the early 1940s by the National Theatre Movement of Australia, but it was the support of Eugene Goossens, conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (SSO) that ensured its selection in preference to sites in the centre of town. Goossens was a driving force behind the project. He had been invited to take over the orchestra by Charles Moses, the General Manager of the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC). In order to match the salary Goossens was receiving at the time from the Cincinnatti Symphony Orchestra, Moses arranged for him to act as Director of the Sydney Conservatorium, which is located in the Royal Botanic Gardens overlooking Circular Quay and Bennelong Point.

At that time, SSO concerts were given in the Sydney Town Hall. Although acoustically adequate, it was hardly a suitable venue for Australia’s top orchestra. It also lacked basic facilities; it was virtually unheatable in winter and concert-goers were forced to don hats and gloves. The Sydney Town Hall management refused to provide any sort of refreshments and the audience had to decamp to the pub across the road at the interval. Many of the regular concert-goers were recent immigrants from Europe where they were used to much better facilities.

The SSO programme of concerts was well established; opera, however, was a minority interest. There were some local amateur groups and the occasional tour from an Italian company, but that was it. As a city, Sydney was overshadowed by Melbourne and was a far cry from the cosmopolitan metropolis it is today. It was something of a backwater where the pubs closed at 6.00pm.

Goossens arrived to take up his post in July 1947 and told the Sydney Morning Herald that he would build up the SSO into one of the six best orchestras in the world; he wanted to create a fine concert hall with perfect acoustics and seating for 3,500 people, a home for an opera company and a smaller hall for chamber music. The brief for the Sydney Opera House was born.

Goossens plugged away for several years with little official response to his idea until 1954 when, through Moses’ good offices, he met the Labor Premier, Joe Cahill, to explain his plans. The response was positive. The decision to hold the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne had prompted Sydney to try and raise its sights and a cultural initiative of this kind was just what was needed. Cahill agreed to call a public meeting to discuss the ‘question of the establishment of an opera house in Sydney.’ The meeting was held in the Sydney Public Library on 20 November of that year and was attended by several hundred people involved in the world of music, theatre and dance as well as civic and business leaders.

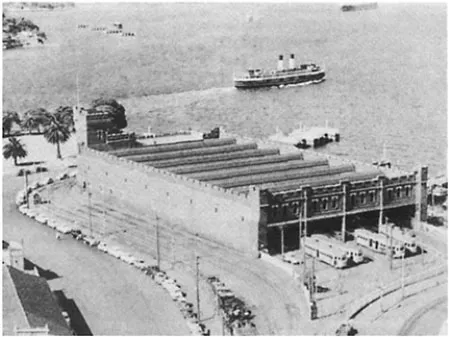

The Fort Macquarie Tram Depot, completed in 1902, which previously occupied the Opera House site.

At the meeting, Cahill proposed that a committee be set up comprising Eugene Goossens, Henry Ingham Ashworth, Professor of Architecture at the University of Sydney, Charles Moses and Stan Haviland, Under Secretary at the Department of Local Government.

Describing his dream for an opera house, Goossens compared it to the San Francisco Opera House, which provided for orchestra, opera, ballet and choral festival in an allpurpose building. Since Goossens had taken over the SSO, the demand for symphonic concerts had more than doubled, necessitating an increasing number of repeat performances; a larger hall accommodating a bigger audience would cut down on these, freeing up the orchestra to support an additional opera programme. He then explained his thinking as to the size of halls—a critical element of the brief and one of the major problems that was to face Utzon some ten years later:

‘At orchestra and choral concerts 3,500 to 4,000 can listen adequately and comfortably. Grand opera is best presented to audiences of 1,800 to 2,500, though theatres in Milan and elsewhere have larger audiences. In my own former town of Cincinnatti, operatic performances are given in buildings accommodating 3,800 patrons. The effective presentation of drama involves much smaller audiences-1,500–1,800.’

He described Malmö Opera House in Sweden, which has a capacity of 1,800 but with the use of travelling walls could be converted into a theatre with 1,200 seats or a hall for recitals with 800:

‘The right approach would be to envisage an auditorium large enough to seat from 3,500 to 4,000 people and to make the auditorium adaptable, by simple mechanism, for opera, for drama and other users, for which a smaller auditorium is desirable.’

Goossens confirmed his view that Bennelong Point was the ideal site: ‘Imagine visitors on a liner coming up Sydney Harbour, seeing this magnificent building and being told “That is Sydney’s opera house”.’ In addition, it was conveniently close to the Sydney Conservatorium and it made sense that his two places of work were close to each other.

At the time, the site housed Sydney’s main tram depot, which the Department of Transport was none too keen to move. They were overridden by Cahill, however, who announced on 17 May 1955 that the new Opera House would be on Bennelong Point, which would provide a setting ‘unique in the world for a building of such monumental character as an opera house’.

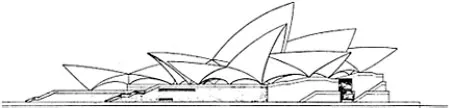

The competition winning design, its form more free-flowing and organic than the completed building.

It was accepted that there should be a competition for the new building, although there was some debate as to whether this should be open to architects internationally or only to Australian practitioners. The NSW Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) suggested, unsurprisingly, that it should be open to nationals only. In this, the Chapter was supported by Walter Bunning, a leading Sydney architect who many expected to win the competition and who was to become a regular critic of Utzon’s designs.

The Sydney Opera House Executive Committee (SOHEC) opted for an international open competition in the hope of attracting the best talent in the world. It was perhaps understandable that it had little sympathy for the local architects’ position: Goossens was born in England and had had an extensive international career; Moses was born in England, emigrating to Australia in the 1920s; Ashworth, also from England, had only arrived in Sydney in 1949 having served in the army in India. His batman accompanied him from England; students of the time recall the batman operating the slide machine for Ashworth’s lectures. It was agreed that the judges should be Leslie Martin, then chief architect of the London County Council and architect of the Royal Festival Hall in London, and Eero Saarinen, architect of a number of major buildings in America including the Kresge Auditorium on the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Campus and the TWA terminal at Idlewild (later Kennedy) Airport. Both these buildings used thin concrete shell roofs. Saarinen was working on the design of the TWA building at the time of the Sydney competition. The other judges were the Australian-born Cobden Parkes, the NSW Government Architect, and Professor Ashworth.

Disaster struck on 9 March 1956 when Goossens, who had been knighted the year before, was arrested at Sydney Airport after he was found in possession of 1,100 ‘indecent items’ including photographs and rubber masks. He resigned from his posts and left Australia two weeks later. The Opera House project had not only lost a great champion, but SOHEC also lost a member who had a comprehensive understanding of the requirements of the brief and the practical experience of using the most sophisticated concert halls around the world.

The winner of the competition was to receive A£5,000, second prize was A£2,000 and third A£l,000 (at the time there was a fixed rate of exchange A£1.25 : £1 sterling); no costs were stated although the brief suggested that ‘extravagance cannot be entertained’. The building requirements stated that the winning scheme was unlikely to be built without changes, so they were looking for a ‘sound basic scheme by a competent architect’.

The detailed brief asked for a building enclosing two halls; the larger one to seat between 3,000 and 3,500 people, the smaller one to hold approximately 1,200. The functions of each hall were set out in order of priority:

Large Hall (Major Hall)

1. Symphony concerts (including organ music and soloists)

2. Large scale opera

3. Ballet and dance

4. Choral

5. Pageants and mass meetings

Small Hall (Minor Hall)

1. Dramatic presentations

2. Intimate opera

3. Chamber music

4. Concerts and recitals

5. Lectures

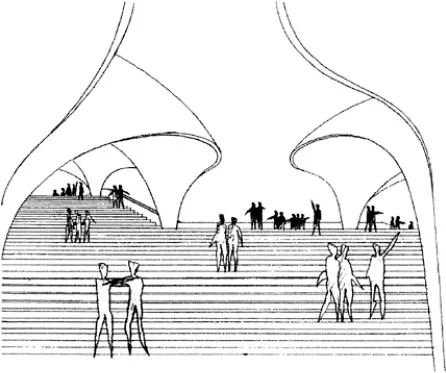

Perspective from main entrance.

The order of priorities is significant in light of the difficulties Utzon had in accommodating the requirements of the brief and of the decision by Hall Todd and Littlemore, the architectural team that took over after Utzon resigned, to drop opera from the Major Hall.

When the competition closed, there were 217 entries from 27 countries, including 61 from Australia and 53 from the UK. On 29 January at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Premier, Joe Cahill, announced that Jørn Utzon of Hellebaek, Denmark was the winner.

Much of the interest in Utzon’s building has focused on the dramatic form of the roofs, but there were other striking and radical features to his design. Unlike all the other entrants, he placed the two theatres side by side, but only managed to do so by ignoring the competition rules; the other entries placed the theatres end to end.

Utzon’s solution had the advantage that the entrance to each hall is equally accessible from the south, the city side. Based on the classical principles of the Greek amphitheatre, he sat the auditoria on the raking podium—a massive plinth which reflected Utzon’s admiration for the Mayan architecture of Mesoamerica—where the floor levels inside were matched by those on the outside. This meant that at every level there was easy egress thus, at a stroke, solving one of the major problems of large public buildings—escape in the case of fire. This brilliant and elegant solution eliminated the need for space-consuming escape stairs that would otherwise be required and was simultaneously economical and safe. However, access to the seats from the entrance foyer required passing on either side of the stage area, which meant Utzon could only provide limited wing space rather than the usual side stages. Apart from providing space for a waiting chorus in grand opera and ballet, the side stages play an essential part in most theatres for scene-changing. Utzon proposed instead a series of lifts that would shift scenery vertically from the service areas below the stage. The stage machinery would be enclosed within the podium along with all the non-public areas, service facilities and an experimental theatre.

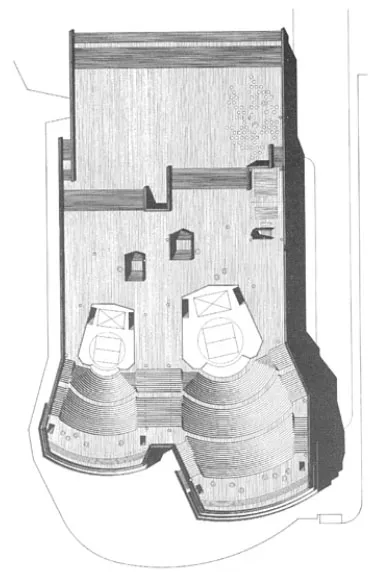

Site plan.

The highly commended entry by John Clark and Ian Plenderleath was typical of the orthogonal architecture of many of the entries with the two halls placed end to end, rather than side by side Utzon did.

If the assessors had enforced the competition conditions, Utzon’s proposals would have been disqualified. He had not included the required drawings, he presented enlarged sketches and no perspective drawing. His presentation was described by the Australian art critic Robert Hughes as ‘nothing more than a magnificent doodle’. But a doodle that illustrated not just the cleverness of the plan but also the iconic potential of the forms. That this powerful image, abstract yet subject to interpretation as clouds, billowing sails, nun’s cowls or mating turtles, can be so simply drawn explains the global impact of the design—its profile converting easily to logotypes, t-shirts, guide book covers and souvenir gewgaws.

The site requirements stated that, ‘the building may be located anywhere on the site, but should not be placed right on the boundary’, and that an entry would be disqualified if ‘it exceeds the limit of the site as outlined on the site plan’. Utzon’s scheme exceeded the site boundaries to the west.

The brief asked for 3,000 to 3,500 seats in the Major Hall, as Goossens had recommended. Utzon’s proposals could not accommodate these numbers. The client later reduced the requirement to 2,800, but this too turned out to be unachievable.

The cavalier attitude of the assessors to the rules of the competition caused much chagrin among the unsuccessful competitors, but more importantly the width of the site was to prove critical in the years to come as Utzon struggled to squeeze sufficient accommodation onto the site.

Paul Boissevain, of Boissevain and Osmond, who won third prize had experience of concert halls prior to entering the competition. They worked with theatre consultants and acousticians for six months to produce their entry and Boissevain realized immediately when he saw Utzon’s plan the problems there would be fitting in all the required accommodation. ‘It was a brilliant conception, but fatally flawed.’

Martin and Saarinen had lunch with the English architect, Trevor Dannatt, shortly after the judging where Saarinen made it quite clear that both he and Martin had lighted on the Utzon design as being in an entirely different league from the rest of the competitors.

The assessors’ report said, ‘We consider this scheme to be the most original and creative submission… The white sail-like forms of the shell vaults relate as naturally to the harbour as the sails of its yachts.’ In defence ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 A magnificent doodle

- Chapter 2 Collaboration and creativity

- Chapter 3 The move to Sydney

- Chapter 4 A quart into a pint pot

- Chapter 5 The turn of the screw

- Chapter 6 ‘You have forced me to leave’

- Chapter 7 The aftermath

- Chapter 8 Ars longa, vita brevis

- Bibliography

- Index