![]()

PART I

War and the Crisis

of the Spanish Monarchy

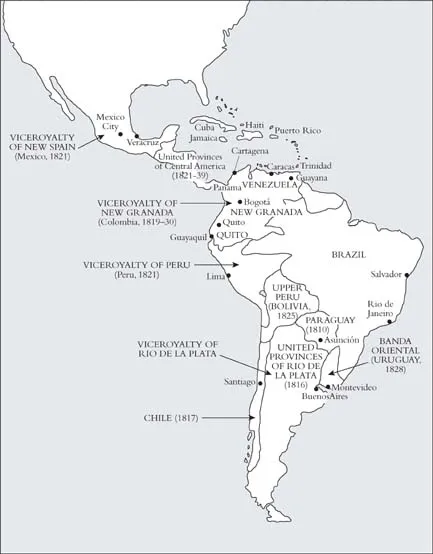

MAP 1. Spanish America

![]()

1

WAR IN THE SPANISH EMPIRE

In 1808, the peoples of the Spanish monarchy entered into a period of war and political convulsion that was without precedent in the history of the Spanish world. The great upheaval began within Spain itself, when Spaniards reacted against Napoleon's removal of the Bourbon King Ferdinand VII by fighting back against the French forces that occupied their country; it then spread across the Atlantic as Spanish Americans responded to the reverberations of the crisis in Spain. Thus, from 1810, Spain's war against France in the Iberian Peninsula was paralleled by the outbreak of wars of a different kind in Spanish America, where the crown's subjects fought among themselves to appropriate the authority of the displaced king.

The combination of these events was entirely novel, as were their outcomes. It is true that Spain had fought foreign armies on Spanish soil previously (as in the War of the Spanish Succession at the beginning of the eighteenth century and the War of the Convention at its end). The Spanish crown had also faced challenges to its authority from outlying kingdoms in its composite monarchy (from the Dutch, the Portuguese, and the Catalan rebellions of the seventeenth century to the large regional rebellions in the viceroyalties of New Granada and Peru in the late eighteenth century). But the combination of war and revolution that spread throughout the Spanish world after 1808 was a crisis of a different order, unique in both character and consequences. The removal of the legitimate king took away the touchstone of the monarchical system, which bound the Hispanic world together, causing it to fragment in many parts. Once broken, the great structure of monarchy was not readily repaired. For while some sought to bring it together again as a “Spanish nation,” others sought to build it anew, creating separate states that sustained themselves. Thus, during the two decades after 1808, the Spanish monarchy was transformed from within, amid a complex process of political demolition and reconstruction, war and revolution.

The Bourbon Century

The great crisis was unexpected, but the political storm that caused it did not issue from cloudless skies. Spain's Bourbon kings were increasingly buffeted by external turbulence, arising from competition between the leading European powers, which, over the course of the eighteenth century, became more intense and globalized. This turbulence took on a new scale and ferocity during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars of the late 1790s and early 1800s, but its origins go back to the early 1700s, when Philip of Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV, succeeded to the throne of the Spanish monarchy. By making possible the future merger of France and Spain under a single dynasty, his succession as Philip V of Spain provoked an international struggle that set the pattern for much of the warfare between the leading colonial powers over the course of the eighteenth century. On one side, France wanted access to American silver—whether through direct trade with Spanish America or indirectly through Spain; as Louis XIV observed, the main object of the war in the Indies was trade and the wealth it produced.1 Britain and the Dutch, on the other hand, also wanted greater access to Spanish American markets and resources; indeed, Britain entertained hopes of creating a commercial hegemony over Spain comparable to that which it imposed on Portugal by the Methuen Treaty, with its privileged access to Brazilian trade.2 Britain and the Dutch Republic thus joined a coalition with Austria, which claimed that the throne should go to a Habsburg, to oppose French annexation of Spain and, with it, the emergence of an immensely rich and powerful Franco-Spanish bloc at the heart of Europe.

The ensuing War of the Spanish Succession (1702–13) ended in compromise. The powers recognized PhilipV on the understanding that he renounced his claim to the French throne and abjured any right to unite France and Spain; Britain secured important commercial concessions that gave access to Spanish American markets, and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) restored stability to the international system around a new set of principles.3 This did not, of course, forestall the renewal of war between the opposing blocs. On the contrary, Utrecht simply recognized that war was the mechanism for making the periodic adjustments needed to sustain a balance between powers of unequal strength, and it was followed by a century of increasingly intense competition between the leading European states.

After the Bourbon succession, the main priority for successive Spanish kings was to rebuild Spain's power and prestige after decades of Habsburg retreat and to confront the shift in international relations announced by the War of the Spanish Succession, particularly the emergence of Britain as a naval power.4 PhilipV initiated the revival of Spanish power with policies designed to establish a more unified and centralized state, with structures of government that would draw power to the king and away from his most powerful nobles.5 Coupled with these reforms was a new emphasis on strengthening Spain's capacity to project military power. When Philip V inherited the throne, Spain's army was small and weak, and Spain's navy even more enfeebled.6 By 1704, PhilipV had embarked on military reforms that set the direction for his successors. He established a new army based on Spanish soil and replaced the outdated system of the tercios with the modern military system of regiments, battalions, and companies. This standing army was, according to some historians, the beginning of a “military monarchy” quite different from its predecessors. Senior military officers were appointed to leading administrative positions, notably as viceroys and captains-general in both Spain and Spanish America, and as this policy continued under successive Bourbon kings, it brought a militarization of the upper echelons of Bourbon government, with key posts increasingly allotted to senior army officers chosen for their proven merit rather than simply their social connections.7

Philip V's ministers also initiated administrative and economic reforms aimed at exerting closer control over the Americas. A Ministry of the Indies was created in 1714, followed by the establishment of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1719 (the first new viceroyalty created in more than 150 years); they also introduced new measures for strengthening Spain's economic relations with the colonies by reorganizing the transatlantic fleet system in 1720.8 These reforms marked a new departure for the monarchy and set new directions for its policies, in line with a new conception of monarchy. Under the Habsburgs, the American territories had been regarded as kingdoms in a composite monarchy; the Bourbons, by contrast, aspired to turn them into subordinate colonies organized for the benefit of the metropolitan power in a unitary monarchy ruled from Madrid.

The other major new direction under Bourbon rule was the development of a foreign policy that tied Spain more tightly to France. The War of Succession was the first of a series of wars in which Spain fought on the side of France against Britain, in a pattern of conflict that was increasingly associated with competition for overseas trade and territory. Between 1700 and 1808, Spain engaged in nine international wars, eight of them against Britain. In the first half of the eighteenth century, these were concentrated in the Mediterranean and aimed at recovering Gibraltar and Minorca and annexing Italian territories for Bourbon princes. In the latter part of the century, most wars involved competition outside Europe and sprang from struggles over trade and territory in the Americas, where Spain and France tried to hold back British commercial encroachments and territorial expansion.

The War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–48) was the first round in these wars for empire, stemming from conflict over British violations of Spain's commercial monopoly in America and aggravated by British pretensions to take and hold territory, either by invasion or by encouraging Spain's American subjects to seize independence under British protection.9 In the event, British warmongers achieved little of permanent value, and less than a decade later, a greater war for empire broke out when Anglo-French clashes in North America triggered the start of the Seven Years' War (1756–63).

The war was a turning point for the Bourbon monarchy. Spain suffered less than France, which lost Canada to the British, but Spain's loss of Havana and Manila, however temporary, delivered a tremendous shock to Spain's new king, Charles III. The capture of Havana in 1762 had, in the first place, revealed unexpected weakness in Spanish American defenses. But this wasn't all. By taking Canada from France and Florida from Spain, Britain had made itself the major colonial power in North America, and this, coupled with its bases in the Caribbean, greatly enhanced its capacity to threaten Spanish trade and territory in both North and South America. Defeat in the Seven Years' War thus provoked a swift reevaluation of Spanish strat-egy.10The question of American defenses now came to the forefront of Madrid's attention, and, in the wake of the Peace of Paris, Charles III and his ministers became increasingly committed to a strategy that focused on the Atlantic and America.

The Evolution of Imperial Strategy

Compared to Britain, Spain faced formidable strategic and logistical challenges in defending its empire. British American territories were concentrated in two relatively small geographical regions—the eastern seaboard of North America and the eastern Caribbean—both with good maritime connections to the metropolis. Spanish America, on the other hand, spread over a huge expanse of North and South America and included territories that looked to the Pacific as well as the Atlantic. Spanish America was, moreover, an assemblage of largely unconnected geopolitical entities, each of which had developed independently. New Spain, Cuba, and the other Spanish Caribbean islands, the Isthmus of Panama, Venezuela, New Granada, Peru, Chile, and Río de la Plata were all distinctive economic regions with very different combinations of human and material resources, governments that reported separately to Madrid, and marked differences in their ability to communicate with the center (communications with Peru and Chile, for example, were much slower than those with the Caribbean islands or Venezuela, which had ready access to the main Atlantic sea lanes). There was, then, no single colonial nucleus to defend but several, many of them very distant from the others.

In these circumstances, Spain had evolved a strategy for imperial defense that focused on key points in its far-flung territories.11 The primary goal was to defend Spanish Atlantic commerce by fortifying the entrepôts for the great mercantile fleets at Havana, Cartagena, Portobelo, Panama, Lima, and Callao. Another crucial aim was to defend territory where there was pressure from foreign nations (notably in the Caribbean, where the French, English, and Dutch had established colonies on territories claimed by Spain). A third, more minor defensive concern was to guard frontier zones against hostile Indians (in northern Mexico, for example, or southern Chile, where there was also a risk that they might aid foreign invaders).

During the eighteenth century, this long-standing strategy was modified to take account of new threats created by international competition. Whereas the first Bourbons had set out to create a larger, more efficient navy and to send more Spanish soldiers to serve as garrison troops in the American plazas fuertes and as reinforcements in times of war, Charles III's ministers went a step further, with a wider strategy for America. At its core was a new approach to the American territories, which aimed to ensure that Spanish America provided more resources for its own governance and defense, while also enlarging the economic and fiscal base needed to underpin Spain's mercantile and naval power. While previous Bourbon policies often had an improvised air, Charles III's policies were more coherent. Between the mid-1760s and the late 1780s, a program of interconnected reform unfolded, aimed at economic development, closer administration, and defense in depth in the main regions of Spanish America. The fundamental strategic aim was, of course, to defend the integrity of Spain's American empire, and it found its military expression in a strategy designed for deterring and containing British attacks.12

Seen in...